Earlier this morning I posted this to Twitter:

I’m of the opinion that “voice”—an author’s voice, authorial voice, etc.—is something that can be switched on and off, manipulated, revised, built upon, etc. as you spend your life #writing and trying new things and getting better at it.

And of course I stand by that, having seen nothing in the last couple hours to change my mind. But the question of “voice” is a complicated one. It’s relatively easy to teach craft things like sentence structure, punctuation, and even some storytelling ideas like intention/obstacle and so on, but voice? How could anyone like me possibly tell you what exact word should go exactly there, at least in a story or novel you haven’t even started writing yet? That’s crazy.

Ultimately, voice, however you play with it, develop it, and try to master it, is unique to each author, and might be the most sacred of the sacred aspects of the art of fiction.

In some effort to dig at least a bit deeper into the unknown, I saved three quotes from interviews in The Paris Review’s long-running The Art of Fiction series, and I’ll start with author Allan Gurganus in the Spring 2021 issue, Number 236:

Beginning writers see language as a means to an end, the paint used to coat your house. But language is the whole game, it’s not the frosting on the cake, it’s the cake, milk, sugar, flour, wheat. How accountable and original and mellifluous is the building material? That counts most of all. Our primal duty is to the hive’s queen bee. She is either/or. She is language itself. We’re mainly here to guard and renew her. Our regeneration depends on her.

As I said—sacred. This is the heart of writing, the thing, as Gurganus says, that we’re here to protect, to honor, to do with as we please, yes, but always in the hope of advancing her.

So then how do we actually do that? How do we find exactly the right word that helps us move our unique stories forward in our unique voices? Do we, as Arthur Quiller-Couch infamously (I say because I think he was wrong) commanded: “murder your darlings?” Or can we learn, as the brilliant Arundhati Roy has (as she said in The Art of Fiction No. 249, The Paris Review #237, Summer 2021) that maybe the first word that comes to mind is the right one?

Sometimes people think of language as something that you construct or choose. But, for me, it is never that. It arrives organically, to tell the story that needs to be told. It comes to me, like as an audio track, as music almost. When I write, I don’t write a lot and then redraft and throw things away. It’s more like I hear it. And then there’s an enhancement, but there isn’t a great amount of redrafting. Recently I was tidying up my cupboards and I found all these papers, sections of Utmost Happiness. They were written eight years ago, and there are pages, whole paragraphs, in which nothing has changed. It’s almost like these sentences and phrases appear as colored threads, and then it is a question of weaving them into a fabric.

Even as someone with no religious, spiritual, superstitious, or metaphysical component to my life, I’m a firm believer in a sort of internal “magic”—what we can default refer to as “inspiration.” Anyone can learn craft, no one can learn talent. Yeah, you either got it or you ain’t, but if you got it, listen to it! And like Arundhati Roy most of it will be good, but not necessarily all of it. The equally brilliant Toni Morrison, also in The Paris Review, said:

The difficulty for me in writing—among the difficulties—is to write language that can work quietly on a page for a reader who doesn’t hear anything. Now for that, one has to work very carefully with what is in between the words. What is not said. Which is measure, which is rhythm, and so on. So, it is what you don’t write that frequently gives what you do write its power.

By this I think, okay, don’t murder your darlings, but don’t let them run wild, either. There still has to be some intent behind telling a story.

Something to consider, at the very least.

—Philip Athans

Follow me on Twitter @PhilAthans…

Link up with me on LinkedIn…

Friend me on GoodReads…

Find me at PublishersMarketplace…

Or contact me for editing, coaching, ghostwriting, and more at Athans & Associates Creative Consulting.

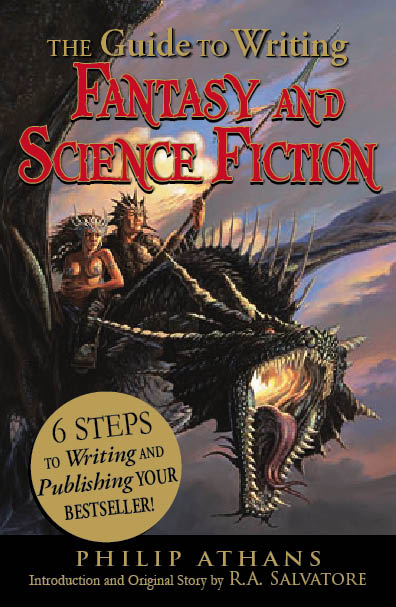

Science fiction and fantasy is one of the most challenging—and rewarding!—genres in the bookstore. But with best selling author and editor Philip Athans at your side, you’ll create worlds that draw your readers in—and keep them reading—with

“don’t murder your darlings, but don’t let them run wild, either.” I like that!

With darlings, it is always this: will anyone other than the writer properly appreciate it, especially in context.

I wrote a line that really resonated with me as a subtle way to say a lot. The man had been born into war. His lover, the narrator, said something like “straining to hear, that you might step into harm’s way, thus to evade it.” You see, if you step into the path of a bullet meant for your little sister, and die accordingly, then she is the one who has to suffer.

But the writing around it was straightforward action sci-fi or enough so as to suggest that one should take the narrator more at face value. So it will definitely need reworking, if that concept is to make it in to the text.

Just before taking your darling off stage consider this. There’s no harm if it goes over most of your reader’s heads, like the DaVinci Codes (not the book but the secret codes described therein.) So, keep them if they can delight that one subtle reader without bothering the rest of us.