Being the holiday season, we recognize the treasures of the past: childhood memories of Christmas and the people we shared those special days with. My grandmothers were very influential personalities in my life. They both continue on as angels visiting me when I need them, climbing Jacob’s Ladder back and forth between heaven and earth. ( Warning– this is a very emotional piece of writing.)

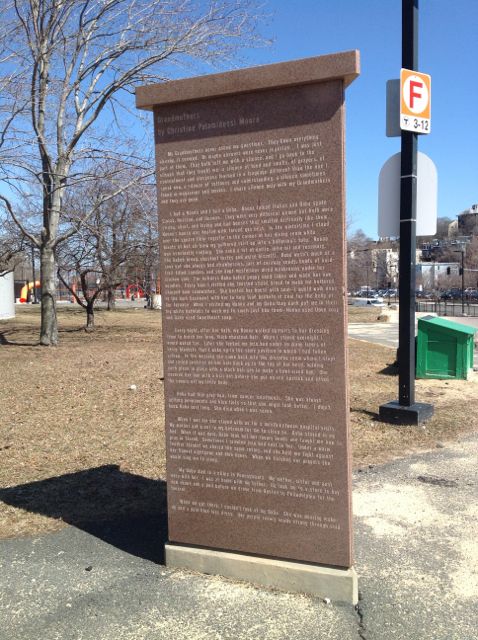

Grandmothers

by Christine Palamidessi

Engraved on a granite monolith and installed outside the Jackson Square transit station on Boston’s Orange Line ——————————————————–

My grandmothers never asked me questions. They knew everything already, it seemed. Or maybe answers were never that important. I was just part of them. They both left me with a silence, and I go back to the silence that they taught me—a silence of food and smells, of prayers, of contentment and closeness learned in a language different than the one I speak now, a silence of softness and understanding, a silence sometimes found in magazines and movies. I share silence only with my grandmothers and they are gone.

I had a Nonna and I had a Baba. They were very different women but they were both strong, short, and loving and had houses that smelled distinctly like them. Nonna’s house was heated with forced gas heat; in the wintertime I stood over the square floor register of her dining room and blasts of hot air blew my skirt like a ballerina’s tutu. Nonna was constantly cooking. She used a lot of garlic, olive oil and rosemary; she baked bread, chestnut tortes, and anise biscotti. Baba on the other hand wasn’t much of a cook but she always had strawberries, bowls of hard-filled candies, and she kept mysterious dried mushrooms under her kitchen sink. Every time I visited she would toast sliced bread to make me a buttered ham sandwich. She heated her house with coal and I would walk down to her dark, dirt-floored basement with her to help load buckets of coal into the belly of her furnace. And, when I visited my Nonna and my Baba, they each would put me in their big white bathtubs to wash me to smell just like them—Nonna used Dove Soap and Baba used Sweetheart Soap.

Every night after her bath, my short Nonna walked upstairs to her dressing room to brush her long, thick chestnut hair. When I stayed at her house, I would watch her do her hair. Afterwards she would tuck me under so many layers of heavy blankets that I woke up in the same position in which I had fallen asleep. In the morning she would come back into the dressing room and roll sections of her long hair up to the top of her head, holding each piece in place with a black hairpin. She covered her bun with a hair net before she put on red lipstick and lifted the covers off my small body.

Baba had thin gray hair, from cancer treatments, and she was always getting permanents and blue tints so that she might look better. I didn’t know Baba very long. She died when I was seven.

When I was six she stayed with us for a month between hospital visits. My mother put a cot in my bedroom for me to sleep on. Baba stayed in my bed. When it was dark, Baba took out her rosary beads and taught me how to pray. Sometimes I would crawl into bed next to her. Under a warm blanket we shared the same rosary. She held me tight against her flannel nightgown and thin bones. When we finished our prayers she would sing me to sleep.

Baba died in a clinic in Pennsylvania.

When I got to the funeral home, I couldn’t look at her. She was wearing make-up and a pale blue lacey dress. Her purple rosary beads strung through cold fingers and her eyes were closed. I couldn’t crawl in next to her and I got sick and refused to go into the room where she lay.

The next day a hearse took her. My parents, sister, aunts , uncles, and cousins went with Baba but I stayed in a building that I think was a school, which was next to the church where they had had a funeral mass. I named the new doll that my father just had bought for me Pia, after the grandmother that was still alive.

Baba was gone. I grew up adoring Nonna. She let me wear lipstick when my mother thought I was much too young, she made me clothes , taught me how to cook, and how to speak Italian. Together, in her basement, we would pluck feathers off the peasants and ducks. As we singed the bird’s flesh over a gas flame, Nonna would tell me stores about her life in Lucca and the life she left behind. At night, on the big red sofa in her living room, I would lean up against Nonna while she knit slippers. After a while she’d shift her soft arms and I would put my head on her lap. Sometimes the TV was on; sometimes we were just quiet together. Sometimes I would open Arriana, an Italian fashion magazine, and read out loud to her.

Nonna always knew. “Christine, I think you are married and you’re not telling us,” she once said to me after I had left home. But Nonna never scolded me.

She died of a heart attack in a hospital during a routine check-up.

At her wake, just like at Baba’s wake, I couldn’t look at the body. My father didn’t understand and pulled me with him to the edge of her casket to hold him while he cried. Nonna’s hair was rolled up in a bun on top of her head, she held a red rosary in her hand, and her hazel eyes had closed to us forever. My head turned and I hugged my tall, tall father as he stooped down to my shoulder and we walked away.

After Nonna was buried everyone went back to her white house to eat and to tell stories. We drank the last few bottles of home made wine that she had stored in her basement. Then everyone went home but me. I stayed in my Nonna’s house and sat on her red sofa, taking in what was left of her smell. I remembered the gowns she had made for me, copied from her fashion magazine; how she had guided my fingers to teach me to knit; how she stood beside me while I stirred polenta so that I would learn to make it smooth, without dry lumps; I remembered killing a crate full of quails with her—we twisted their thin necks and blood squirted everywhere; I remembered digging up a bushel full of dandelions in a damp green field.

I said goodbye to Nonna in the same way I has said goodbye to my Baba twenty years earlier—alone in a space that still held their spirit, alone and with a silence that I could share with no one but them.

“Grandmothers” printable story to read out loud that is engraved on

granite monolith at Boston’s Orange Line Station, Jackson Square.

Leave a comment