As winter descends in the northern hemisphere and those who are blessed with home and hearth settle in with warm beverages and toasty blankets, there’s a sense of snug security in these shorter, colder days. But sometimes, magical creatures lurk in the long winter nights, especially in the colder climes of Nordic and Slavic regions. Scholar and author Victoria Audley shares tales of magick in that beautifully frigid region of the world.

Quiet descends on the forest at night, when all the sounds of active life fade away; the soft rustling of leaves in the breeze and the low calling of nocturnal animals seem loud in the absence of other noise. But if you find yourself there at that time, you may hear another sound join the night’s chorus: a lively tune and the rhythmic thudding of feet, dancing on the soft forest floor.

The ballet Giselle draws on folktales of the wilis, portraying them as the restless ghosts of wronged women. The wilis are just one of a number of Slavic forest spirits, collectively known by the umbrella term, vila. Similar to nymphs, they are largely seen as benevolent and generous, but they are not without their sinister edge. At night, they gather to dance in the forests they protect, and any mortal who dares present themselves uninvited will be forced to dance until they drop dead.

As guardians of nature, vile are revered and honoured with gifts left at their sacred caves, wells, or forest groves. In return for these offerings, they may bestow one of their many gifts, such as powers of healing or granting favourable weather. As with all fairies, respect is key; their considerable power is not to be tested, lest their wrath be incurred.

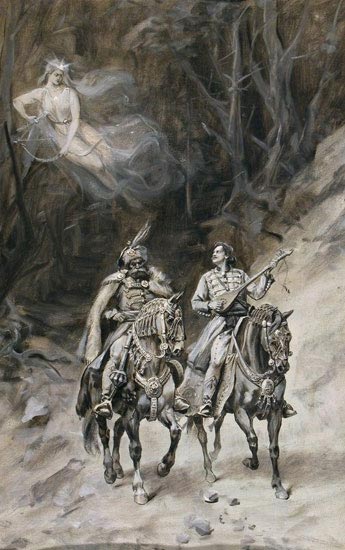

A Vila, Ravijojla, Who Revenges for a Song

The Serbian folk hero, Prince Marko, learned this lesson the hard way. He was raised by a vila, and was gifted his companion, a magical talking horse named Šarac, by a vila as well. You’d think he would know, then, not to cross a vila, but in one of his most famous adventures, he does just that.

Marko and his sworn brother, Miloš, were travelling together through the mountains. Overcome with weariness, Marko asked Miloš to sing him a song to lift his spirits. Miloš warily declined, revealing that the vila Ravíjojla promised to kill him if she heard him singing. But Marko insisted, so Miloš sang.

Of course, Ravíjojla heard him, and that night, while they slept, she shot Miloš with two arrows: one through his heart, and one through his throat. Marko jumped on his horse and raced after Ravijojla, and his magical steed began gaining on her. He caught up to her, beating her with his golden mace until she pleaded with him to spare her in return for herbs to save Miloš’s life. Marko agreed, and Miloš was thus saved.

Antics of legendary folk heroes aside, the vile are largely masters of their own fate. It is said that they occupy a space between mortality and immortality — that they will never die except when they choose to die. Their power over nature gives them the ability to create and destroy in equal measure.

Another story, “The Maiden Who Was Faster Than A Horse,” features a heroine who was born of the vile by being shaped out of snow, raised by the wind and the dew, clothed in leaves, and given beauty by flowers. She issued a challenge, saying that she would run a race against anyone on horseback. If they overtook her, they would win her, but if she won, she would kill all who had made the attempt.

Her association with nature helped her in the race. She plucked a hair from her head and as she threw it behind her it became a forest, blocking the way of the racers. Her tears formed a river that nearly drowned all the riders and their horses. But the tsar’s son managed to cross the river and commanded her to stop in the name of God. Unable to resist, she froze, and the rider picked her up and put her on his horse. When he reached the finish line, however, he looked behind him and saw nothing. The maiden had vanished into thin air.

The Rusalka, Goddess Kostroma, Who Loved Her Brother

While the vile are typically pleasant until crossed, their cousins the rusalki are vicious through and through. Women whose deaths were violent or unhappy — usually murdered by lovers or abandoned while pregnant — may become rusalki, and that disquiet follows them beyond the grave. Associated with bodies of water, they lurk in the shallows and lure men into their domain, where they entangle them in their long hair and drown them.

During the Slavic festival of Green Week, the dangerous rusalki are more active, and extra care must be taken not to fall afoul of them. As the peril from these restless spirits increases, a large part of the festival is dedicated to appeasing the souls of the dead. Birch trees are associated with the dead, and offerings and decorations are left in the trees to hopefully calm the angry spirits. Sometimes, a birch is named in honour of a rusalka, and at the end of the festival, the birch is drowned to banish the rusalka and bring rain for crops.

One famous rusalka was the goddess Kostroma. She and her twin brother Kupalo played in a field together as children. One day, they heard singing from a pair of legendary birds. Kostroma listened to Alkonost, the bird of joy, but Kupalo heard Sirin, the bird of sorrow, and was lost.

Years later, Kostroma walked alone by a river, making a flower wreath and boasting that the wind could not knock it from her head (meaning she would never marry). Of course, the wind did carry the wreath off her head and into the hands of a man in a nearby boat. The two fell in love and were married. It was not until after their marriage that it was revealed that the man was Kupalo.

In grief, Kupalo threw himself into a fire. Kostroma threw herself into a lake, but instead of peaceful rest, she found herself turned into a rusalka. She prowled the lake’s edges, capturing young men she believed to be Kupalo and drowning them. The gods witnessed Kostroma’s despair and granted the pair mercy, turning them into a flower with yellow and blue petals: yellow, for Kupalo’s fire, and blue, for Kostroma’s lake.

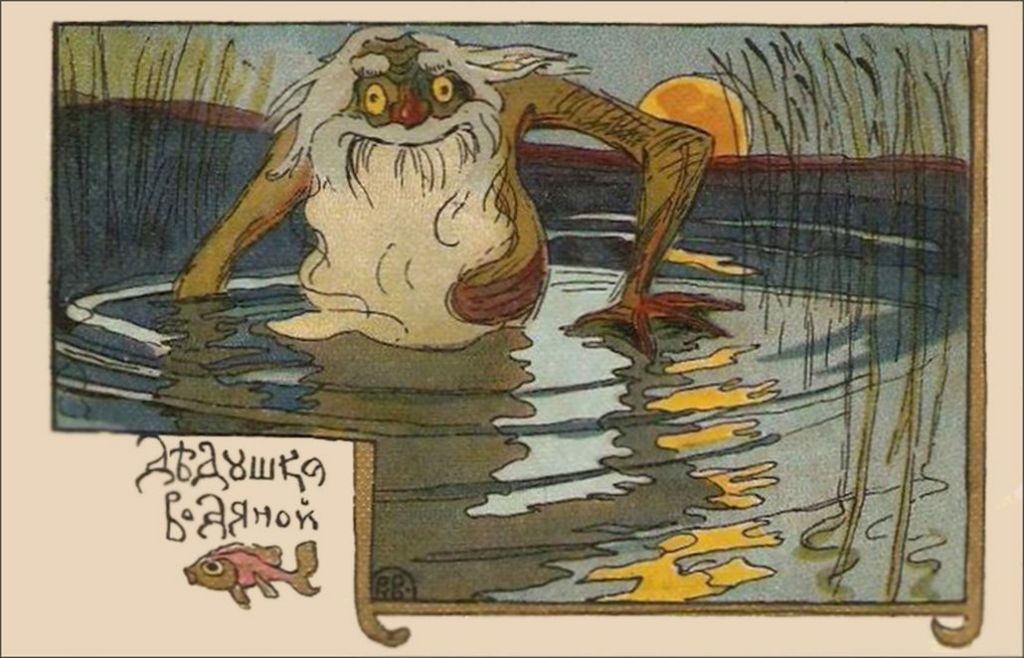

Tsar Vodyanik, Ruler of the Vodyanoy, Meets a Hapless Farmboy

The male counterpart to the rusalka is the vodyanoy or vodník. Often described as a frog-like man, the vodyanoy is a malevolent and dangerous water spirit known for drowning those who venture into their territory. Unlike the rusalka, the vodyanoy aren’t associated with the undead; rather than being the resurrected spirits of those who died violently or in deep sorrow, the vodyanoy are fairies through and through.

In the north of Russia, legends speak of Tsar Vodyanik, the ruler of the vodyanoy. Though it is never a good idea to cross any of the vodyanoy, he is certainly the one to whom most respect should be shown. A cautionary tale featuring Tsar Vodyanik tells of a farmer with three sons. The youngest, Ivan, was idle and witless. He would not help with the farm work or do anything to help his family.

One night, as Ivan was walking home, he came to the edge of the river. In the early spring, the melted snow overfilled the river, and the current was fast and strong. There was no way to cross.

A voice called to him from the water. “Give me a tribute, and I will carry you across on my back,” it said.

Ivan knew there could only be one owner of that voice. “Tsar Vodyanik,” he replied, “I have no tribute, but I’d like you to carry me across all the same.”

His demand was met with silence, at first. Then a figure rose from the river: his eyes burned red, his skin was mottled blue-green, and his beard was made of moss. Ivan barely had time to take in the sight before the cold water rose at Tsar Vodyanik’s command and pulled him under.

The next day, Ivan’s father searched for him. Looking into the river, he saw Ivan, but as he had never seen him before; he bore the scars and bruises of Tsar Vodyanik’s attacks, but even more shocking, Ivan was working hard, tilling and landscaping the bottom of the river. While on dry land, Ivan refused to work, and now, he works forever in the employ of Tsar Vodyanik under the water.

The spirits of Slavic folklore are generous and sinister, beautiful and horrible in turn. As with all spirits, they command respect, and when that respect is betrayed, their retribution is swift and terrible. Leave a gift for them if you travel the forests, and remember not to join in any dancing circles to which you’ve not been invited, or it may be the last thing you do.

Victoria Audley is a writer and folklorist with degrees in philosophy and museum education. She has performed at the Texas Renaissance Festival as a Highland dancer and as the White Swan. When she isn’t writing ghost stories and fairytales, she can be found baking, reading, and attempting to convince the neighbourhood cats to let her pet them. She currently lives in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, England, with her husband and twenty-one fake crows.

https://vcaudley.carrd.co/https://twitter.com/vcaudley