Read-Me-First: Much is being posted about the coronavirus on a daily, or even hourly, basis – sometimes a bit too much with fake news / data / pictures coupled with conspiracy theories, accusations of racism, and doomsday predictions. This blog post – live updated from time to time – aims to filter out the signal amidst the noise: data & opinions on the COVID-19 that (a) I think are worth knowing & reflecting about, and (b) are inevitably colored with my own biases & POV. Do your own research, form your own (informed) opinions, and stay safe!

Table of Contents (updated April 17, 2020)

- [Set the Stage] Other than masks, stop up some humor too

- [Science] Getting familiar with COVID-19 symptoms (vs. cold, flu, allergy)

- [Science] Understanding how fast the virus spreads and incubates

- [Protective Measures] Response of Individuals: Stock-Up vs. Laissez-Faire

- [Protective Measures] Response of Governments: Lock-Down vs. Herd Immunity

- [Thinking Smart] What a conspiracy theory teaches us about critical thinking

- [Thinking Smart] Veterans merely make better guesses – nobody knows for sure

- [Thinking Smart] “Aha” moments from working from home

- [Thinking Smart] Defining information

- [Thinking Smart] What went wrong with media coverage? A failure, but not of prediction

[Set the Stage] Other than masks, stock up some humor too

If you have not yet heard about the “coronavirus disease 2019” (COVID-19) – which is aptly named with a “19” suffix because we were obviously certain it would spread into 2020 and achieve monopoly over this year’s headlines (joking) – you must be living in a cave.

Rest assured, even if that were the case, I would not mock you. On the contrary, I would envy you, because living in a cave like Robinson Crusoe these days is probably one of the safest ways to protect yourself from the coronavirus. 🙂 Moreover, if you were able to get Wi-Fi connection in your cave, you could post on social media with glorious hashtags like #not-lonely-when-am-alone, #perfect-social-distancing, #responsible-self-quarantine etc.,

Just joking (again). We all need some positive energy in times like this. Some wise folk once said: “If you can’t laugh about it, you lose.” I, for one, am a big fan of John Oliver’s funny, sarcastic & witty take at the recent coronavirus news on “Last Week Tonight” (HBO, March 1, 2020):

Let’s not forget to keep some happy smiley faces up even when COVID-19 was called a pandemic by the WHO and the stock market + oil market + crypto market + [insert your past-favorite / now-most-hated market] are trapped by NOVGRA-20, a shorthand for “novel gravitational force 2020”. Can the Einstein-of-our-times come up with a new theory of relativity to explain what the h*** is going on?

Since searching for the next Einstein-of-our-times is too challenging, I opted for an easier option – searching on Google about what is interesting to know about the COVID-19. Here is your curated feed on “uncommon sense” about the coronavirus: not-your-typical headlines, yet probably worthy of attention.

[Science] Getting familiar with COVID-19 symptoms (vs. cold, flu, allergy)

To start with, let us first familiarize ourselves with what the virus does. As Peter Attia, MD with training in immunology, said in a podcast, the coronavirus mainly attacks the type II pneumocyte cell that makes surfactin. Surfactin lets the air sacs of the lungs to overcome the tension on the surface and hence open successfully. In other words, without sufficient surfactin, individuals could suffer from respiratory collapse. Dr. Attia recommends all infected persons with difficulty breathing to seek medical attention ASAP – regardless of their age.

COVID-19 could be tricky to diagnose because of overlapping symptoms with the cold, the flu and allergies. This article from Business Insider (March 2020) gives a good comparison of the symptoms across the 4 diseases.The key point is the three most common symptoms of COVID-19 are: fever + dry cough + shortness of breath.

The good news is: if you are sneezing and have a runny nose, it is very unlikely that you have COVID-19 – the flu or allergies are probably to blame.

The important footnote is: while nausea and diarrhea are rare for COVID-19, these symptoms could still be “early cues of infection (of COVID-19)” and thus should not be taken lightheartedly.

[Science] Understanding how fast the virus spreads and incubates

When it comes to studying the spread of the virus, a key concept to know is the viral coefficient, denoted by “R”. “R” stands for the number of people that each infected person goes on to infect. You may have also heard about R0, which stands for the viral coefficient in a community with no natural immunity against the virus and takes no special protective measures. Getting a fair estimate of R (and R0) could help us assess how viral the virus is and how effective interventions are:

“In the long term, the only way that this pandemic can actually end is for the R value of the virus to plunge below 1, consistently, in every part of the world, for a prolonged period of time.”

“A framework for thinking through what’s next for COVID-19”

(March 11, 2020)

I recommend reading “An in-depth look at four academic models of the Wuhan coronavirus outbreak’s spread” (January, 2020) for a concise summary of what scientists say (or infer) about the spread of the virus. The key takeaway on the virality factor is this:

“[T]here is still not an academic consensus on the basic replication number of the Wuhan coronavirus. Models range from finding an Ro of 1.4 after assuming a latent period of 14 days, to finding one of 4.0 after assuming only 4 days.“

“An in-depth look at four academic models of the Wuhan coronavirus outbreak’s spread”

(January, 2020)

Next, let us look at the incubation period of the coronavirus. In this March, 2020 study led by Johns Hopkins University, the researchers find the median incubation period is around 5 days:

“There were 181 confirmed cases with identifiable exposure and symptom onset windows to estimate the incubation period of COVID-19. The median incubation period was estimated to be 5.1 days (95% CI, 4.5 to 5.8 days), and 97.5% of those who develop symptoms will do so within 11.5 days (CI, 8.2 to 15.6 days) of infection. These estimates imply that, under conservative assumptions, 101 out of every 10,000 cases (99th percentile, 482) will develop symptoms after 14 days of active monitoring or quarantine.”

The Incubation Period of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) From Publicly Reported Confirmed Cases: Estimation and Application

(March 10, 2020)

The Johns Hopkins research suggests that 14 days is a reasonable length for quarantine – cases that have longer incubation periods are possible yet unlikely outliers:

“Based on our analysis of publicly available data, the current recommendation of 14 days for active monitoring or quarantine is reasonable, although with that period, some cases would be missed over the long-term.”

5.1 days incubation period for COVID-19

(March 9, 2020)

Despite progress in understanding the viral coefficient (R) and the length of the incubation period, we are still not sure about when someone is contagious – in particular whether a person is contagious during the incubation period. The website of the US Center for Disease Control (accessed on March 16, 2020) reads: “[D]etection of viral RNA does not necessarily mean that infectious virus is present…it is not yet known what role asymptomatic infection plays in transmission. Similarly, the role of pre-symptomatic transmission (infection detection during the incubation period prior to illness onset) is unknown.“

That being said, Bill Hanage, an associate professor of epidemiology from Harvard, believes the answer “is an unambiguous yes” when it comes to “a person can transmit before they are aware they might be infectious.” Though please do note Hanage’s statement is yet to be backed with peer-reviewed research.

[Protective Measures] Response of Individuals: Stock-Up vs. Laissez-Faire

On the question of how to respond to the COVID-19 outbreak, the responses fall on two-ends of the spectrum (for individuals): go full force or do (almost) nothing. We see a juxtaposition of two contrasting camps: (1) Camp-Stock-Up rushing to supermarkets and stocking up on years of toilet paper vs. (2) Camp-Laissez-Faire wandering the streets without masks – assuming they have or are able to get masks – either a/ thinking optimistically that the COVID-19 is not that dangerous and everyone is making a fuss or b/ thinking pessimistically that all prevention measures are useless because they would get infected sooner or later.

Where should we pick our stance between the two extremes? Below is a stance that I find to be reasonable, which thinks about social distancing the way we think about car safety: “not as a single binary decision to go Full Turtle and shelter in place, but as a collection of little risk-reducing behaviors that add up to a big win“:

“To really get your mind around how this works, think about all the little things you do to manage risk when driving a car: wear a seat-belt, use a turn signal, drive the speed limit, don’t drink or text and drive, have your brakes checked regularly, etc. Each of these things helps a little, and when done together they all add up to a dramatically safer driving experience — both for you and those you share the road with — than if you didn’t do any of them at all.”

Even if you can’t go full lockdown right now, you can still #FlattenTheCurve

(March 13, 2020)

Another key point this author points out is “every new day is riskier than the previous one” – at least in the short term – as the number of infections increases and we are not yet fully equipped with dealing with the disease. What this entails is it makes sense for each individual to progressively level-up their self-protection every single day, at least until (a) we see reliable signs that the spread of the virus has been contained and / or (b) we have developed a solid cure and / or vaccine.

Most of us are probably working from home, but for those who are working in the office or in public places, consider this piece of advice:

“Take on progressively more social and reputational risk in order to reduce your physical risk: e.g., If you’re working a retail counter tomorrow and an obviously ill customer approaches you, discretely excuse yourself for the restroom at the risk of having that person try to get you fired. You might want to start using sick days next week. Get bold and creative with how to distance yourself in-the-moment, and be more willing to offend people as this progresses.”

Even if you can’t go full lockdown right now, you can still #FlattenTheCurve

(March 13, 2020)

“Be more willing to offend people.” If you are working in the office and a colleague is coughing, ask him / her to work from home or see a doctor. Do not be afraid to offend your colleague, because it is a responsible thing to do for both you and your colleague and everyone else in the office. Plus, if you were asking in a nice way and explain your rationale, most people in your colleague’s shoes should be able to understand.

[Protective Measures] Response of Governments: Lock-Down vs. Herd Immunity

The response of governments around the world could be broadly put into 2 types:

- Camp Eradicate: represented by China, this group takes a resolute stance including city-wide lock-downs and quarantine at the cost of disrupting economic activities;

- Camp Herd Immunity: represented by the UK (which has since then modified its stance to be more hard-line) is to focus on “flattening the curve,” i.e., focus on protecting the more vulnerable people. Instead of trying to eradicate the virus, this camp would try to slow down the spread of the disease a bit so as to “flatten the curve,” i.e., a slower spread of the disease could prevent over-burdening the healthcare system.

Scott Adams asks an interesting question about whether these two camps could co-exist in harmony. As long as Camp #2 Herd Immunity exists, does this mean Camp #1 Eradicate cannot possibly exist or sustain its success?

The UK’s proposal of “herd immunity” has been under criticism:

Some argue that “herd immunity” is a by-product of preventive measures, and should not be mistaken as an end in itself:

“[T]alk of ‘herd immunity as the aim’ is totally wide of the mark. Having large numbers infected isn’t the aim here, even if it may be the outcome. A lot of modellers around the world are working flat out to find best way to minimise impact on population and healthcare. A side effect may end up being herd immunity, but this is merely a consequence of a very tough option – albeit one that may help prevent another outbreak.”

Adam Kucharski, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

[Thinking Smart] What a conspiracy theory teaches us about critical thinking

A Reddit post from February 2020 went viral with the title: “Quadratic Coronavirus Epidemic Growth Model seems like the best fit” – it posits that the total case numbers reported by China fits “uncannily” well with a quadratic curve (15 days’ of data, R-squared value of .9995). Given none of the current epidemiological models supports a quadratic growth curve, the Reddit post makes a not-so-subtle hint that the Chinese numbers may be fabricated to fit a quadratic curve.

And the situation quickly gets dramatic, and like all (good) dramas do, the situation quickly gets messy with people pointing their fingers at the Chinese government and / or the WHO for allegedly making up and / or covering up the number of total cases in China.

Before anyone gets excited thus far, let us take a look at both sides of the debate. Ben Hunt from Epsilon Theory – one of my frequently-read and highly-recommended blogs on “the narratives that drive markets, investing, voting and elections” – sides with the Reddit skeptic:

“All epidemics – before they are brought under control – take the form of a green line, an exponential function of some sort. It is impossible for them to take the form of a blue line, a quadratic or even cubic function of some sort. This is what the R-0 metric of basic reproduction rate means, and if – as the WHO has been telling us from the outset – the nCov2019 R-0 is >2, then the propagation rate must be described by a pretty steep exponential curve. As the kids would say, it’s just math.”

“[T]o be clear, at some point the original exponential spread of a disease becomes ‘sub-exponential’ as containment and treatment measures kick in. But I’ll say this … it’s pretty suspicious that a quadratic expression fits the reported data so very, very closely. In fact, I simply can’t imagine any real-world exponentially-propagating virus combined with real-world containment and treatment regimes that would fit a simple quadratic expression so beautifully.”

Ben Hunt, “Body Count”

(February 10, 2020)

On the same day when Ben Hunt published his article, there is an Op-Ed published defending the validity of the case numbers, with a title that sums up the author’s stance: “No, 2019-nCoV case numbers were not fabricated to fit a curve”. It points out a few loopholes with the skeptics’ conspiracy theory:

- Add a few more days of data to the original data-set (of 15 days) and what we get “is far from being a perfect quadratic”;

- “If you look at the data from outside China, which is definitely not being faked by China, and fit a quadratic to cumulative case numbers, you’ll get a similarly eye-catching R-squared value of .992.”

- Fitting data into a quadratic function is easier than it may sound: “Any data whatsoever with n points can be fit perfectly, with absolutely no error, using a polynomial of degree n-1.”

The author goes on to say we should pay attention to the fact that “modern statistical software can fit many types of models to the same data,” and therefore we should be extra-cautious with what conclusions we draw – especially when the data has a small sample size:

“[A]s our Redditor friend acknowledges, he tried many models before choosing the one with the most eye-catching R-squared value.”

“And the curve of a growing epidemic has some properties that inherently can make it kind of similar to a quadratic. It will be monotonically upward, and growing at an increasing rate. This means the regression calculation’s job is made easier by this crude similarity, and allows those eye-catching R-squared numbers. The R-squared value is calculated using the square of the differences between the model and reality, so it punishes a few large deviations more harshly than many small ones. That is, the joint information of the two curves being high is really just the observation that in general the curves look pretty similar, not a clinching judgment that the curve was faked using a model.”

“No, 2019-nCoV case numbers were not fabricated to fit a curve”

(February 10, 2020)

The author concludes with this stance: “We’re not saying the data is reliable, just that it’s not faked,” citing “even if every single authority in the world were the most competent they could possibly be and were reporting everything they knew with complete candor, the data would still not be accurate, because many cases are latent with no symptoms, and even among symptomatic cases, most are not known to public health authorities.” In short, it is impossible to have “accurate” (and timely) data when it comes the total number of cases – just as it is impossible to have “perfect” testing that covers every single case in real time.

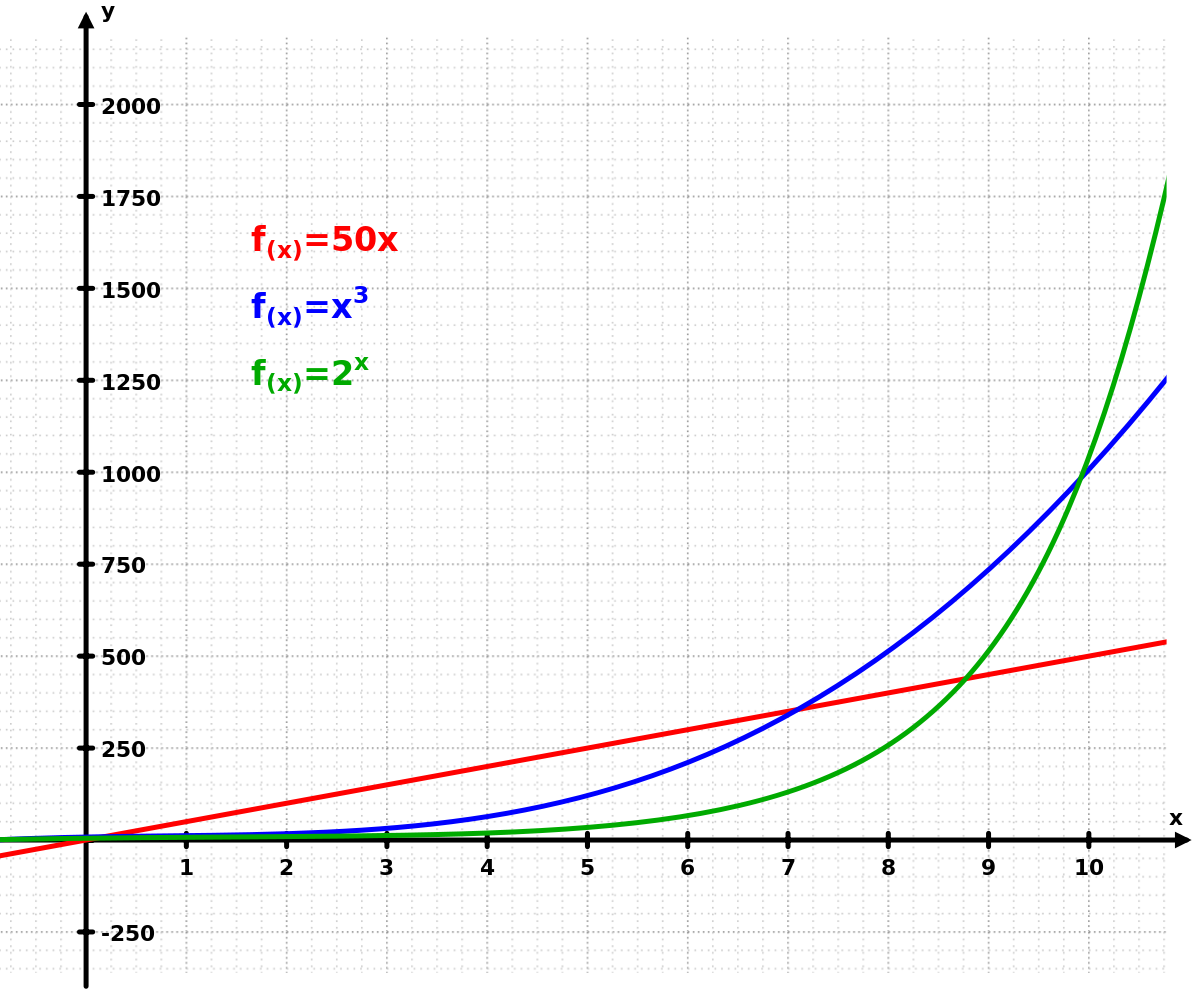

The purpose of me sharing the above is not to tell you which side you should pick – to be honest, I think the real question here is not who to side with, but how to analyze data (& inferences, opinions) critically. To help us remember how easy it is to misinterpret data – whether intentionally or by accident – I would like to show you this graph where a quadratic curve and an exponential curve look very similar within a small range of data:

Here is an explanation of the graph above:

“We generated two curves, one exponential and one quadratic, that both start at 100 on day 1 and end at 1440 or so on day 29. We then fit a quadratic to the exponential, and vice versa. These data really are synthetic and perfect, and we’re fitting the wrong model to each one. But in both cases, the fit is close and the R-squared value is .97 when we fit the exponential to the quadratic, and .994 when we fit the quadratic to the exponential.“

“You can see that both fitted models start to fail at the end, as the exponential data grows faster than the quadratic model will allow, and vice versa.”

“No, 2019-nCoV case numbers were not fabricated to fit a curve”

(February 10, 2020)

It may be a good time to remind everyone of Cowen’s first law from Tyler Cowen, professor of economics: “There is something wrong with everything (by which I mean there are few decisive or knockdown articles or arguments, and furthermore until you have found the major flaws in an argument, you do not understand it).” I would say that is a good attitude to adopt when we read anything, what do you say? And that is a trick question – because if you agree with me, then it implies you think there is nothing wrong with my statement, but that is self-defeating of Cowen’s First Law; if you disagree with me, then it implies you think there is something wrong, which is an example that fits Cowen’s First Law.

Okay – I am just having fun with logic games. 🙂 The point is: do your own research, do your own research on the pro vs. against, and do your own research from every possible angle. Everyone could be wrong. Everyone must be wrong in some way – the only difference is whether you spot where they are wrong or not.

[Thinking Smart] Veterans merely make better guesses – nobody knows for sure

Howard Marks is the co-founder of Oaktree Capital Management, one of the largest investors in distressed securities. He publishes memos on his views on the market, investing, current affairs and other topics. In his latest memo “Nobody Knows II”, which I think is worth a 10-minute read from start to end, Howard shared his take on the coronavirus and the recent market downturn.

Howard breaks down information about the virus into 3 types:

“As Harvard epidemiologist Marc Lipsitch said on a podcast on the subject, there are (a) facts, (b) informed extrapolations [inferences] from analogies to other viruses and (c) opinion or speculation. The scientists are trying to make informed inferences. Thus far, I don’t think there’s enough data regarding the coronavirus to enable them to turn those inferences into facts. And anything a non-scientist says is highly likely to be a guess.“

Memo from Howard Marks: Nobody Knows II

(March 3, 2020)

In Howard’s previous memo called “You Bet” (January, 2020), he shared some quotes by Annie Duke, a PhD dropout who later became what Howard calls “the best-known female professional poker player” with over $4 million winnings from tournaments:

“[W]orld-class poker players taught me to understand what a bet really is: a decision about an uncertain future…[T]here are exactly two things that determine how our lives turn out: the quality of our decisions and luck. Learning to recognize the difference between the two is what thinking in bets is all about.”

“[W]inning and losing are only loose signals of decision quality. You can win lucky hands and lose unlucky ones…What makes a decision great is not that it has a great outcome. A great decision is the result of a good process, and that process must include an attempt to accurately represent our own state of knowledge. That state of knowledge, in turn, is some variation of ‘I’m not sure.’…What good poker players and good decision-makers have in common is their comfort with the world being an uncertain and unpredictable place…instead of focusing on being sure, they try to figure out how unsure they are, making their best guess at the chances that different outcomes will occur.”

“[W]e can make the best possible decisions and still not get the result we want. Improving decision quality is about increasing our chances of good outcomes, not guaranteeing them.“

Annie Duke, “Thinking in Bets: Making Smarter Decisions When You Don’t Have All the Facts”

(February, 2018)

Nowadays with (almost) everyone being called (or calling themselves) an “expert” and giving their (solicited and unsolicited) opinions on the Internet, let’s take a step back to ask ourselves what it means to be an expert:

“An expert in any field will have an advantage over a rookie. But neither the veteran nor the rookie can be sure what the next flip will look like. The veteran will just have a better guess.“

Annie Duke, “Thinking in Bets: Making Smarter Decisions When You Don’t Have All the Facts”

(February, 2018)

I applaud this tweet of Francois Balloux, a computational / system biologist working on infectious diseases. In sharing his opinion of the virus, he candidly admits: “Predictions from any model are only as good as the data that parametrised it. There are two major unknowns at this stage. (1) We don’t know to what extent covid-19 transmission will be seasonal. (2) We don’t know if covid-19 infection induces long-lasting immunity.” I recommend reading his full Twitter thread here:

We need more consciously-responsible experts as such – experts who are candid in sharing their opinions and in admitting that they could be wrong and they could never be perfectly right. Nobody ever knows for sure. I’d like to share this quote on humility:

“Humility not in the idea that you could be wrong, but given how little of the world you’ve experienced you are likely wrong, especially in knowing how other people think and make decisions.”

Morgan Housel, “Different Kinds of Smart”

(September 27, 2018)

[Thinking Smart] “Aha” moments from working from home

This Tweet on technical difficulties people run into when they are working from home is a vivid illustration of the point: it is time to rethink work and work-tech.

The thing with a business continuity plan is it rarely gets the credit when business continues as usual. To the contrary, it is only missed (or blamed) when the business cannot continue as usual.

Re-imagining work extends to re-imagining the office building – this Tweet predicts voice or gesture controlled activation could become more prevalent. Imagine your office building lift becomes a mini Siri, Alexa or Google Assistant. Try saying: “Hey Lift, take me to the 19th floor.”

Other than conversations on work-tech, this “hot” Tweet takes it to the level of class consciousness:

[Thinking Smart] “Aha” moments from working from home

With the surge of cases worldwide comes a surge in “information” about the coronavirus – though the information we see vary greatly in quality. I strongly recommend Defining Information from the Stratechery blog that shares insights on how to think about information:

“Given that over 90% of the PCs in the world ran Windows, writing a virus for Windows offered a far higher return on investment for hackers that were primarily looking to make money. Notably, though, if your motivation was something other than money — status, say — you attacked the Mac.”

“I suspect we see the same sort of dynamic with information on social media in particular; there is very little motivation to create misinformation about topics that very few people are talking about, while there is a lot of motivation — money, mischief, partisan advantage, panic — to create misinformation about very popular topics. In other words, the utility of social media as a news source is inversely correlated to how many people are interested in a given topic.“

Defining Information (Stratechery, April 2020)

In simple terms, as more people start talking about a topic, the average quality of the information you get drops. This is not surprising for two reasons: (a) you are more likely to hear higher number of repetitions of popular opinions and narratives; (b) there is a higher incentive for people to create or spread misinformation on a hot topic.

The Stratechery blog goes on to propose some helpful heuristics on how to deal with different types of information:

“For emergent information, like the coronavirus in February, you need a high degree of sensitivity and a high tolerance for uncertainty.”

“For facts, like the coronavirus right now, yo uneed a much lower degree of sensitivity and a much lower tolerance of uncertainty: either something is verifiably known or it isn’t.”

Defining Information (Stratechery, April 2020)

[Thinking Smart] What went wrong with media coverage? A failure, but not of prediction

Slate Star Codex is one of my favorite blogs by far. Scott Alexander’s post A FAILURE, BUT NOT OF PREDICTION is an insightful take on what went wrong with the media coverage on the coronavirus. A key concept that Scott discusses is that of probalistic reasoning:

“A surprising number of these people had signed up for cryonics – the thing where they freeze your brain after you die, in case the future invents a way to resurrect frozen brains. Lots of people mocked us for this – ‘if you’re so good at probabilistic reasoning, how can you believe something so implausible?’ I was curious about this myself, so I put some questions on one of the surveys.”

“The results were pretty strange. Frequent users of the forum (many of whom had pre-paid for brain freezing) said they estimated there was a 12% chance the process would work and they’d get resurrected. A control group with no interest in cryonics estimated a 15% chance. The people who were doing it were no more optimistic than the people who weren’t. What gives?”

“I think they were actually good at probabilistic reasoning. The control group said ‘15%? That’s less than 50%, which means cryonics probably won’t work, which means I shouldn’t sign up for it.’ The frequent user group said ‘A 12% chance of eternal life for the cost of a freezer? Sounds like a good deal!'”

A failure, but not of prediction (Slate Star Codex, April, 2020)

Scott summarized it well when he said: “Making decisions is about more than just having certain beliefs. It’s also about how you act on them.“

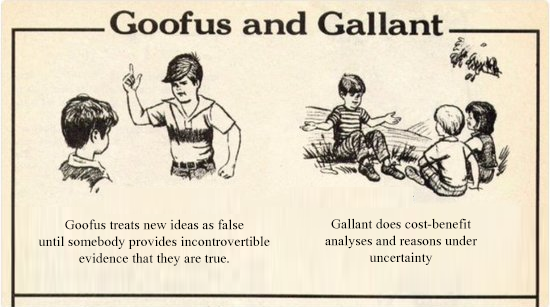

He shared a diagram showing two types of people: Goofus and Gallant. Goofus requires “incontrovertible evidence” before believing something is true, i.e., false until proven true. On the contrary, Gallant embraces uncertainty and does not look at things in an all-or-nothing fashion: he reasons in probability.

Scott argued that people behaved like Goofus when the coronavirus first started to spread:

“I think people acted like Goofus again.”

“People were presented with a new idea: a global pandemic might arise and change everything. They waited for proof. The proof didn’t arise, at least at first. I remember hearing people say thing like ‘there’s no reason for panic, there are currently only ten cases in the US’. This should sould like ‘there’s no reason to panic, the asteroid heading for Earth is still several weeks away’. The only way I can make sense of it is through a mindset where you are not allowed to entertain an idea until you have proof of it. Nobody had incontrovertible evidence that coronavirus was going to be a disaster, so until someone does, you default to the null hypothesis that it won’t be.“

“Gallant wouldn’t have waited for proof. He would have checked prediction markets and asked top experts for probabilistic judgments. If he heard numbers like 10 or 20 percent, he would have done a cost-benefit analysis and found that putting some tough measures into place, like quarantine and social distancing, would be worthwhile if they had a 10 or 20 percent chance of averting catastrophe.“

A failure, but not of prediction (Slate Star Codex, April, 2020)

Goofus-Gallant reasoning could also be applied to the debate about whether face masks are effective:

“Goofus started with the position that masks, being a new idea, needed incontrovertible proof. When the few studies that appeared weren’t incontrovertible enough, he concluded that people shouldn’t wear masks.”

“Gallant would have recognized the uncertainty – based on the studies we can’t be 100% sure masks definitely work for this particular condition – and done a cost-benefit analysis. Common sensically, it seems like masks probably should work. The existing evidence for masks is highly suggestive, even if it’s not utter proof. Maybe 80% chance they work, something like that? If you can buy an 80% chance of stopping a deadly pandemic for the cost of having to wear some silly cloth over your face, probably that’s a good deal. Even though regular medicine has good reasons for being as conservative as it is, during a crisis you have to be able to think on your feet.”

A failure, but not of prediction (Slate Star Codex, April, 2020)

[To be updated from time to time]