Father Ken Vavrina’s new book “Crossing Bridges” charts his life serving others

For a man whose vocation as a priest is a half-century long and counting, it may come as a surprise that Father Ken Vavrina had no notion of entering that life until, at age 18, a voice instructed him to attend seminary school. It was a classic calling from on high that he didn’t particularly want or appreciate. He had his life planned out, after all, and it didn’t include the priesthood. He resisted the very thought of it. He rationalized why it wasn’t right for him. He wished the admonition would go away. But it just wouldn’t. He couldn’t ignore it. He couldn’t shake it. Deep inside he knew the truth and rightness of it even though it seemed like a strange imposition. In the end, of course, he obeyed and followed the path ordained for him. His rich life serving others has seen him minister to Native Americans on reservations, African-Americans in Omaha’s inner city, occupying protestors at Wounded Knee, lepers in Yemen. the poor, hungry and homeless in Calcutta, India and war refugees in Liberia. He worked for Mother Teresa and for Catholic Relief Services. He’s been active in Omaha Together One Community. There have been many other stops as well, including Italy, Cuba, New York City and rural Nebraska. He has crossed many cultural and geographic bridges to engage people where they are at and to respond to their needs for food, water, medicine, shelter, education, counseling. Everywhere he’s gone he’s gained far more from those he served than he’s given them and as a result he’s grown personally and spiritually. He has attained great humility and gratitude. His simple life of service to others has much to teach us and that’s why he commissioned me to help him write the new book, Crossing Bridges: A Priest’s Uplifting Life Among the Downtrodden. It was a privilege to share his remarkable life and story in book form. Here is an article I’ve written about him and his many travels. It is the cover story in the November 2015 issue of the New Horizons. I hope, as he does, that this story as well as the book we did together that this story is drawn from inspires you to cross your own bridges into different cultures and experiences. Many blessings await.

The book is available at http://www.upliftingpublishing.com/ as well as on Amazon and BarnesandNoble.com and for Kindle. The Bookworm is exclusively carrying “Crossing Bridges” among local bookstores.

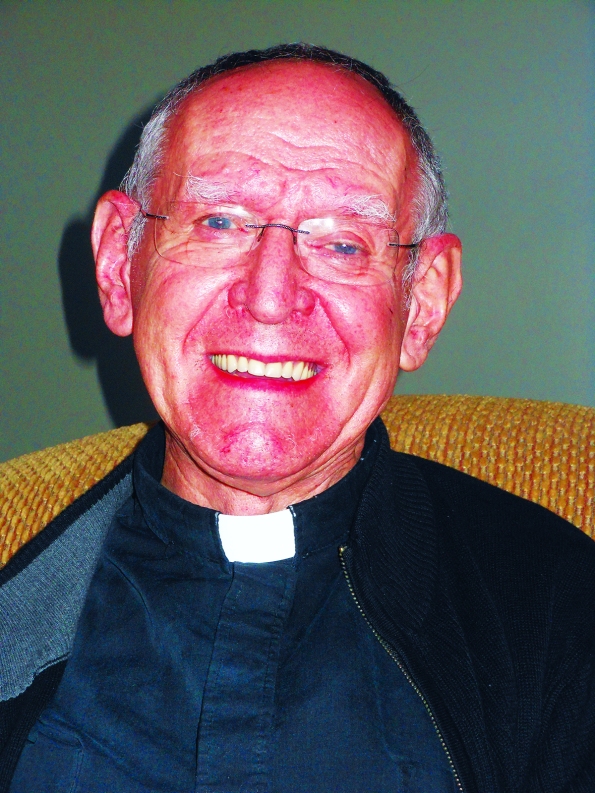

Father Ken with Mother Teresa

Father Ken Vavrina’s new book “Crossing Bridges” charts his life serving others

©by Leo Adam Biga

Appeared in the November 2015 issue of the New Horizons

NOTE:

My profile of Father Ken Vavrina contains excerpts and photos from the new book I did with him, Crossing Bridges: A Priest’s Uplifting Life Among the Downtrodden.

A Life of Service

Retired Catholic priest Father Kenneth Vavrina, 80, has never made an enemy in his epic travels serving people and opposing injustice.

“I have never met a stranger. Everyone I meet is my friend,” declares Vavrina, who’s lived and worked in some of the world’s poorest places and most trying circumstances.

It’s no accident he ended up going abroad as a missionary because from childhood he burned with curiosity about what’s on the other side of things – hills, horizons, fences, bridges. His life’s been all about crossing bridges, both the literal and figurative kind. Thus, the title of his new book, Crossing Bridges: A Priest’s Uplifting Life Among the Downtrodden, his personal chronicle of repeatedly venturing across borders ministering to people. His willingness to go where people are in need, whether near or far, and no matter how unfamiliar or forbidding the location, has been his life’s recurring theme.

For most of his 50-plus years as a priest he’s helped underserved populations, some in outstate Neb., some in Omaha, and for a long time in developing nations overseas. Whether pastoring in a parish or doing missionary work in the field, he’s never looked back, only forward, led by his insistent conscience, open heart and boy-like sense of wanderlust. That conscience has put him at odds with his religious superiors in the Omaha Catholic Archdiocese on those occasions when he’s publicly disagreed with Church positions on social issues. His tendency to speak his mind and to criticize the Catholic hierarchy he’s sworn to obey has led to official reprimands and suspensions.

But no one questions his dedication to the priesthood. Always putting his faith in action, he shepherds people wherever he lays his head. He lived five years in a mud hut minus indoor plumbing and electricity tending to lepers in Yemen. He became well acquainted with the slums of Calcutta, India while working there. He spent nights in the African bush escorting supplies. He spent two nights in a trench under fire. The archdiocesan priest served Native Americans on reservations and African-Americans in Omaha’s poorest neighborhoods. He befriended members of the American Indian Movement, Black Panthers and various activists, organizers, elected officials and civic leaders.

His work abroad put him on intimate terms with Blessed Mother Teresa, now in line for sainthood. and made him a friend of convenience of deposed Liberia, Africa dictator Charles Taylor, now imprisoned for war crimes. As a Catholic Relief Services program director he served earthquake victims in Italy, the poorest of the poor in India, Bangladesh and Nepal and refugees of civil war in Liberia.

He found himself in some tight spots and compromising positions along the way. He ran supplies to embattled activists during the Siege at Wounded Knee. He was arrested and jailed in Yemen before being expelled from the country. He faced-off with trigger-happy rebels leading supply missions via truck, train and ship in Liberia and dealt with warlords who had no respect for human life.

If his book has a message it’s that anyone can make a difference, whether right at home or half way around the globe, if you’re intentional and humble enough to let go and let God.

“There is nothing remarkable about me…yet I have been blessed to lead a most fulfilling life…The nature of my work has taken me to some fascinating places around the world and introduced me to the full spectrum of humanity, good and bad.

“Stripping away the encumbrances of things and titles is truly liberating because then it is just you and the person beside you or in front of you. There is nothing more to hide behind. That is when two human hearts truly connect.”

Even though he’s retired and no longer puts himself in harm’s way, he remains quite active. He comforts and anoints the sick, he administers communion, he celebrates Mass and he volunteers at St. Benedict the Moor. Occasional bouts of the malaria he picked up overseas are reminders of his years abroad. So is the frozen shoulder he inherited after a botched surgery in Mexico. His shaved head is also an emblem from extended stays in hot climates, where to keep cool he took to buzz cuts he maintains to this day. Then there’s his simple, vegan diet that mirrors the way he ate in Third World nations.

This tough old goat recently survived a bout with cancer. A malignant tumor in his bladder was surgically removed and after recouping in the hospital he returned home. The cancer’s not reappeared but he has battled a postoperative bladder infection and gout. Ask him how he’s doing and he might volunteer, “I’m not getting around too well these days” but he usually leaves it at, “I’m OK.” He lives at the John Vianney independent living community for retired clergy and lay seniors. He’s more spry than many residents. It’s safe to say he’s visited places they’ve never ventured to.

Father Ken today

Roots

Born in Bruno and raised in Clarkson, Neb., both Czech communities in Neb.’s Bohemian Alps, Vavrina and his older brother Ron were raised by their public school teacher mother after their father died in an accident when they were small. The boys and their mother moved in with their paternal grandparents and an uncle, Joe, who owned a local farm implement business and car dealership. The uncle took the family on road trip vacations. Once, on the way back from Calif. by way of the American southwest, Vavrina engaged in an exchange with his mother that profoundly influenced him.

“I remember my mom telling me, “On the other side of that bridge is Mexico,” and right then and there I vowed, ‘One day I’m going to cross that bridge'”

“I never crossed that particular bridge but I did cross a lot of bridges to a lot of different lifestyles and countries and cultures and it was a great, great, great blessing. You learn so much in working with people who are different.”

One key lesson he learned is that despite our many differences, we’re all the same.

Even though he grew up around very little diversity, he was taught to accept all people, regardless of race or ethnicity. He feels that lesson helped him acclimate to foreign cultures and to living and working with people of color whose ways differed from his.

As a fatherless child of the Great Depression and with rationing on due to the Second World War, Vavrina knew something about hardship but it was mostly a good life. Growing up, he went hunting and fishing with his uncle, whose shop he worked in. He played organized basketball and baseball for an early mentor, coach Milo Blecha.

“All in all, I had a wonderful childhood in Clarkson,” he writes. “It was a simple life. The Church was dominant. There was a Catholic church and a Presbyterian church. Father Kubesh was the pastor at Saints Cyril and Methodius Catholic Church. When he was not saying Mass, Father Kubesh always had a cigar in his mouth. I served Mass as an altar boy. Little did I imagine that he would counsel me when I embarked on studying for the priesthood.”

All through high school Vavrina dated the same girl. His family wasn’t particularly religious and he never even entertained the possibility of the priesthood until he felt the calling at 18. Out of nowhere, he says, the thought, really more like an admonition, formed in his head.

“I was driving a pickup truck on a Saturday morning, about four miles east of Clarkson, when something happened that is still crystal clear to me. I distinctly heard a voice say, ‘Why don’t you go to the seminary?’ Just like that, out of the blue. I thought, This is crazy.“Was it God’s voice?

“Being a priest is a calling, and I guess maybe it was the call that I felt then and there. If you want to give it a name or try to explain it, then God called me to serve at that moment. He planted the seed of that idea in my head, and He placed the spark of that desire in my heart.”

The very idea threw Vavrina for a loop. After all, he had prospects. He expected to marry his sweetheart and to either go into the family business or study law at Creighton University. The priesthood didn’t jibe with any of that.

He says when he told Father Kubesh about what happened the priest’s first reaction was, “Huh?” For a long time Vavrina didn’t tell anyone else but when it became evident it wasn’t some passing fancy he let his friends and family know. No one, not even himself, could be sure yet how serious his conviction was, which is why he only pledged to give it one year at Conception Seminary College in northwest Missouri.

He told his uncle, I’ll give it a shot.” And so he did. One year turned into two, two years turned into three, and so on, and though his studies were demanding he found he enjoyed academics.

He finished up at St. Paul Seminary at the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul, Minn. and was ordained in 1962.

Calling all cultures

His introduction to new cultures began with his very first assignment, as associate pastor for the Winnebago and Macy reservations in far northern Nebraska. Vavrina was struck by the people’s warmth and sincerity and by the disproportionate numbers living in poverty and afflicted with alcoholism. He disapproved of efforts by the Church to try and strip children of their Native American ways, even sending kids off to live with white families in the summer.

His next assignment brought him to Sacred Heart parish in predominantly black northeast Omaha. He arrived at the height of racial tension during the late 1960s civil rights struggle. He served on an inner city ministerial team that tried getting a handle on black issues. When riots erupted he was there on the street trying to calm a volatile situation. The more he learned about the inequalities facing that community, the more sympathetic he became to both the civil rights and Black Power movements, so much so, he says, people took to calling him “the blackest cat in the alley.”

He was an ally of Nebraska state Sen. Ernie Chambers, activist Charlie Washington and Omaha Star publisher Mildred Brown. He befriended Black Panthers David Rice and Ed Poindexter (Mondo we Langa), both convicted in the homemade bomb death of Omaha police officer Larry Minard. The two men have always maintained their innocence..

Vavrina welcomed changes ushered in by Vatican II to make the Church more accessible. He criticized what he saw as ultra-conservative and misguided stands on social issues. For example, he opposed official Catholic positions excluding divorced and gay Catholics and forbidding priests from marrying and barring women being ordained. He began a long tradition of writing letters to the editor to express his views. He’s never stopped advocating for these things.

He next served at north downtown Holy Family parish, where his good friend, kindred spirit and fellow “troublemaker” Jack McCaslin pastored. McCaslin spouted progressive views from the pulpit and became a peace activist protesting the military-industrial complex, which resulted in him being arrested many times. The two liberals were a good fit for Holy Family’s open-minded congregation.

Then, in 1973, Vavrina’s life intersected with history. Lorelei Decora, an enrolled member of the Winnebago tribe, Thunder Bird Clan, called to ask him to deliver medical supplies to her and fellow American Indian Movement activists at Wounded Knee, South Dakota. A group of Indians agitating for change occupied the town. Authorities surrounded them. The siege carried huge symbolic implications given its location was the site of the 1890 Wounded Knee Massacre. Vavrina knew Decora when she was precocious child. Now she was a militant teen prevailing on him to ride into an armed standoff. He never hesitated. He and a friend Joe Yellow Thunder, an Oglala Sioux, rounded up supplies from doctors at St. Joseph Hospital. They drove to the siege and Father Ken talked his way inside past encamped U.S, marshals.

He met with AIM leader and cofounder Dennis Banks, whom he knew from before.

“Then I saw Lorelei and I looked her in the eye and asked, ‘What are you doing here?’ She said with great conviction, ‘I came to die.’ They really thought they would all be killed. They were fully committed…On his walkie-talkie Banks reached the authorities and told them, ‘Let this guy stay here. He’s objective. He’ll let you know what’s going on.’ The authorities went along…that’s how I came to spend two nights at the compound. We bivouacked in a ravine where the Indians had carved out trenches. We used straw and blankets over our coats, plus body heat, to keep warm at night. It was not much below freezing, and there was little snow on the ground, which made the camp bearable.“At night the shooting would commence…the tracers going overhead, the Indians huddled for cover, and several of the occupiers sick with cold and flu symptoms.

“Once back home, Joe and I attempted to make a second medicine supply run up there. We drove all the way to the rim but were turned back by the marshals because the violence had started up again and had actually escalated. When the siege finally ended that spring, there were many arrests and a whole slew of charges filed against the protesters.”

By the late-’70s Vavrina was serving a northeast Neb. parish and feeling restless. He’d given his all to combatting racism and advocating for equal rights but was disappointed more transformational change didn’t occur. He saw many priests abandon their vows and the Church regress into conservatism after the promise of Vatican II reforms. More than anything though, he felt too removed from the world of want. It bothered him he’d never really put himself on the line by giving up things for a greater good or surrendering his ego to a life of servitude.

“I felt I was out of the mainstream, away from the action. Plus, I knew the civil rights movement was…not going to reach what I thought it could achieve…So I decided I was going overseas. I wanted to be where I could do the greatest good. I always felt drawn to the missions…I just felt a need to experience voluntary poverty and to become nothing in a foreign land.“…an experience in Thailand changed the whole trajectory of my missions plan. I was walking the streets of Bangkok…on the edge of downtown…Then I made a wrong turn and suddenly found myself in the slums of Bangkok…everywhere I looked was human want and suffering at a scale I was unprepared for.

“I was shocked and appalled by the conditions people lived in. I realized there were slums all over the world and these people needed help. What was I doing about it? The experience really hit me in the face and marked an abrupt change in my thinking. I looked at my relative affluence and comfortable existence, and I suddenly saw the hypocrisy in my life. I resolved then and there, I was going to change, and I was going to move away from the privilege I enjoy, and I would work with the poor.”

A reinforcing influence was Mother Teresa, whom he admired for leaving behind her own privilege and possessions to tend to the poor and sick and dying. He resolved to offer himself in service to her work.

The nun, he writes, “was a great inspiration..” Nothing could shake his conviction to go follow a radically different path and calling.

His going away had nothing to do with escaping the past but everything to do with following a new course and passion. By that time he’s already worked 15 years in the archdiocese and “loved every minute of it.” He was finishing up a master’s degree in counseling at Creighton University. “Everything was good. No nagging doubts. But I just felt compelled to do more,” he writes.

He asked and received permission from the diocese to work overseas for one year and that single year, he describes, turned into 19 “incredible years helping the poorest of the poor.”

Yemen

He no sooner found Mother Teresa in Italy than she asked him to go to Yemen, an Arab country in southwest Asia, to work with residents of the leper village City of Light.

“I simply replied, ‘Sure,’” Vavrina notes in his book.

In Yemen he witnessed the fear and superstition that’s caused lepers to be treated as outcasts everywhere. In that community he worked alongside Missionaries of Charity as well as lepers.

“My primary job was to scrape dead skin off patients using a knife or blade. It was done very crudely. Lepers, whether they are active or negative cases, have a problem of rotting skin. That putrid skin has to be removed for the affected area to heal and to prevent infection…I would then clean the skin.“I would also keep track of the lepers and where they were with their treatment and the medicines they needed.”

He embraced the spartan lifestyle and shopping at the local souk. He found time to hike up Mount Kilimanjaro. He also saw harsh things. An alleged rapist was stoned to death and the body displayed at the gate of the market. Girls were compelled to enter arranged marriages, forbidden from getting an education or job, and generally treated as property. Yemen is also where he contracted malaria and endured the first sweats and fevers that accompany it.

Yet, he says, Yemen was the place he found the most contentment. Then, without warning, his world turned upside down when he found himself the target of Yemeni authorities. They took him in for seemingly routine questioning that turned into several nights of pointed interrogation. He was released, but under house arrest, only to be detained again, this time in an overcrowded communal jail cell.

He was incarcerated nearly two weeks before the U.S. embassy arranged his release. No formal charges were brought against him. The police insinuated proselytizing, which he flatly denied, though he sensed they actually suspected him of spying. They couldn’t believe a healthy, middle-aged American male would choose to work with lepers.

His release was conditional on him immediately leaving the country. The expulsion hurt his soul.

“Being kicked out of the country, and for nothing mind you, other than blind suspicion, was not the way I imagined myself departing. I was disappointed. I truly believe that if I had been left to do my work in peace, I would still be there because I enjoyed every minute of working with the lepers. There is so much need in a place like Yemen, and while I could help only a few people, I did help them. It was taxing but fulfilling work.”

India

He traveled to Italy, where Catholic Relief Services hired him to manage a program rebuilding an earthquake ravaged area. Then CRS sent him to supervise aid programs in India. After nine months in Cochin he was transferred to Calcutta. Everywhere he set foot, hunger prevailed, with millions barely getting by on a bare subsistence level and life a daily survival test.

Besides supplying food, the programs taught farmers better agricultural practices and enlisted women in the micro loan program Grameen Bank. In all, he directed $38 million in aid annually.

The generous spirit of people to share what little they have with others impressed him. Seeing so many precariously straddle life and death, with many mothers and children not making it, opened his eyes. So did the sheer scale of want there.

“I will never forget my first night in Calcutta. I said to the driver, ‘What are in these sacks we keep passing by?’ ‘Those are people.’ Hundreds upon thousands of people made their beds and homes alongside the road. It was a scale of homelessness I could not fathom. That was my introduction to Calcutta.“I was scared of Calcutta. Of the push and pull and crunch of the staggering numbers of people. Of the absurd overcrowding in the neighborhoods and streets. Of the overwhelming, mind-numbing, heartbreaking, soul-hurting poverty. That mass of needy humanity makes for a powerful, sobering, jarring reality that assaults all the senses…

“…only God knows the true size of the population…I often say to religious and lay people alike, ‘Go to Calcutta and walk the streets for six days and it will change your life forever” Walk the streets there for one day and even one hour, and it will change you. I know it did me.”

Vavrina was reunited there with Mother Teresa.

“I spent a lot of time working with Mother, Whenever she had a problem she would come into the office. If there was a natural disaster where her Sisters worked we would always help with food or whatever they needed.”

He witnessed people’s adoration of Mother Teresa wherever she went. There was enough mutual respect between this American priest and Macedonian nun that they could speak candidly and laugh freely in each other’s company. He criticized her refusal to let her Sisters do the type of development work his programs did. He disapproved of how tough she was with her Sisters, whom she demanded live in poverty and restrict themselves to providing comfort care to the sick and dying.

He writes, “I disagreed with Mother and I told her so. I knew the value of development work. Our CRS programs in India were proof of its effectiveness…she listened to me, not necessarily agreeing with me at all…and then went right ahead and did her own thing anyway…I cried the day I left Calcutta in 1991. I loved Calcutta. Mother Teresa had tears in her eyes as well. We had become very good friends. She was the real deal…hands on…not afraid to get her hands dirty.”

Years later he read with dismay and sadness how she experienced the Dark Night of the Soul – suffering an inconsolable crisis of faith.

“I knew her well and yet I never detected any indication, any sign that she was burdened with this internal struggle. Not once in all the time I spent with her did she betray a hint of this. She seemed in all outward appearances to be quite happy and jovial,” he writes. “However, I did know that she was very intense about her faith and her work. In her mind and heart she was never able to do enough. She never felt she did enough to please God, and so there was this constant, gnawing void she felt that she could never fully fill or reconcile.”

Even all these years later Vavrina says his experience in India is never far from his thoughts.

Liberia

CRS next sent him to Liberia, Africa, where a simmering civil war boiled over. His job was getting supplies to people who’d fled their villages. That meant dealing with the most powerful rebel warlord, Charles Taylor, whose forces controlled key roads and regions.

The program Vavrina operated there dispersed $42 million in aid each year, most of it in food and medicine. As in India, goods arrived by ship in port for storage in warehouses before being trucked to destinations in-country. Vavrina often rode in the front truck of convoys that passed through rebel-occupied territories where boys brandishing automatic weapons manned checkpoints. There were many tense confrontations.

On three occasions Vavrina got Taylor to release a freight train to carry supplies to a large refugee contingent in dire need of food and medicine in the jungle. Taylor provided a general and soldiers for safe passage but Vavrina went along on the first run to ensure the supplies reached their intended recipients.

Everywhere Vavrina ran aid overseas he contended with corruption to one extent or another. Loss through pilfering and paying out bribes to get goods through were part of the price or tax for conducting commerce. Though he hated it, he dealt with the devil in the person of Taylor in order to get done what needed doing. Grim reminders of the carnage that Taylor inflamed and instigated were never lost on Vavrina and on at least once occasion it hit close to home.

“Not for a moment did I ever forget who I was really talking to…I never forgot that he was a ruthless dictator. He was a pathological liar too. He could look you dead in the eye and tell you an out-and-out untruth, and I swear he was convinced he was telling the truth. A real paranoid egomaniac. But in war you cannot always choose your friends.“Hundreds of thousands of innocent people died in Liberia during those civil wars. There were many atrocities. One in particular touched me personally. On October 20, 1992, five American nuns, all of whom I knew and considered friends, were killed. I had visited them at their convent two days before this tragedy. May they rest in peace.”

The killings were condemned worldwide.

His most treacherous undertaking involved a cargo ship, The Sea Friend, he commissioned to offload supplies in the port at Greenville. Only rebels arrived there first. To make matters worse the ship sprung a leak coming into dock. Thus, it became a test of nerves and a race against time to see if the supplies could be salvaged from falling prey to the sea and/or the clutches of rebels. When all seemed lost and the life of Vavrina and his companions became endangered, a helicopter answered their distress call and rescued them from the ugly situation.

Back home

Hs work in Liberia was left unfinished by the country’s growing instability and by his more frequent malaria attacks, which forced him back home to the States. At the request of CRS he settled in New York City doing speaking and fundraising up and down the East Coast. Then he went to work for the Catholic Medical Mission Board, who sent him to Cuba to safeguard millions of dollars in medical supplies for clinics in an era when America’s Cuba embargo was still officially in effect.

During his visit Vavrina met then-Archbishop of Havana, Jamie Ortega, now a cardinal. Vavrina supported then and applauds now America normalizing relations with Cuba.

He also appreciates the progressive stances Pope Francis has taken in extending a more welcoming hand by the Church to divorced and gay Catholics and in encouraging the Church to be more intentional about serving the poor and disenfranchised. The pope’s call for clergy to be good pastors and shepherds who work directly work with people in need is what Vavrina did and continues doing.

“This is exactly what the Holy Father is saying. They need to get out of the office and stop doing just administration and reach out to people who are being neglected. A shepherd reaches out to the lost sheep. Jesus talks about that all the time,” Vavrina says.

As soon as Vavrina ended his missions work overseas he intended coming back to work in Omaha’s inner city but he kept getting sidetracked. Then he got assigned to serve two rural Neb. parishes. Finally, he got the call to pastor St. Richard’s in North Omaha, where he was sent to heal a congregation traumatized by the pedophile conviction of their former pastor, Father Dan Herek.

Vavrina writes, “Those wounds did not heal overnight. I knew going in I would be inheriting a parish still feeling raw and upset by the scandal. Initially my role was to help people deal with the anger and frustration and confusion they felt. Those strong emotions were shared by adults and youths alike.”

During his time at St. Richard’s he immersed himself in the social action group, Omaha Together One Community.

Facing declining church membership and school enrollment, the archdiocese decided to close St. Richard’s, whereupon Vavrina was assigned the parish he’d long wanted to serve – St. Benedict the Moor. As the metro’s historic African-American Catholic parish, St. Benedict’s has been a refuge to black Catholics for generations. Vavrina led an effort to restore the parish’s adjacent outdoor recreation complex, the Bryant Center, which has become a community anchor for youth sports and educational activities in a high needs neighborhood. He also initiated an adopt a family program to assist single mothers and their children. Several parishes ended up participating.

Poverty and unemployment have long plagued sections of northeast Omaha. Those problems have been compounded by disproportionately high teenage pregnancy, school dropout, incarceration and gun violence rates. Vavrina saw too many young people being lost to the streets through drugs, gangs or prostitution. Many of these ills played out within a block or two of the rectory he lived in and the church he said Mass in. He’s encouraged by new initiatives to support young people and to revitalize the area.

Wherever he pastored he forged close relationships. “One of the benefits of being a pastor is that the parish adopts you as one of their own, and the people there become like a family to you,” he writes.

At St. Ben’s that sense of family was especially strong, so much so that when he announced one Sunday at Mass that the archbishop was compelling him to retired there was a hue and cry from parishioners. He implored his flock not to make too big a fuss and they mostly complied. No, he wasn’t ready to retire, but he obeyed and stepped aside. Retirement gave him time to reflect on his life for the book he ended up publishing through his own Uplifting Publishing and Concierge Marketing Publishing Services in Omaha.

Father Ken enjoying our book

“I’ve had a wonderful life, oh my,” he says.

Now that that wonderful life has been distilled into a book, he hopes his journey is instructive and perhaps inspiring to others.

“I wrote the book hoping it was going to encourage people to cross bridges and to reach out to people who otherwise they would not reach out to. That’s exactly what Pope Francis is talking about.”

Besides, he says, crossing bridges can be the source of much joy. The life story his book lays out is evidence of it.

“That story just says how great a life I have had,” he says.

“It is my prayer that the travels and experiences I describe in these pages serve as guideposts to help you navigate your own wanderings and crossings.“A bridge of some sort is always before you…never be afraid to open your heart and speak your mind. We are all called to be witnesses. We are all called to testify. To make the crossing, all that is required is a willing and trusting spirit. Go ahead, make your way over to the other side. God is with you every step of the way. Take His hand and follow. Many riches await.”

Order the book at http://www.upliftingpublishing.com.

Father Ken very noble person. I was fortunate to be associated with him for soem time in Taiz, Yemen. He use to visit lepors to help them. Its almost 43 years but the memories are still fresh. I salute him and my kind regards.

Yashpal Minotra

minotra@outlook.com

LikeLike