Catherine Walshe, Zara Walsh, Lisa Clogher, Pádraig Collins, Michael Byrne

Background: While the benefits of stepped-care psychological interventions, based on cognitive-behavioural principles, have been well established, the published results to date have been predominantly UK-based, urban-centred, and with a multidisciplinary workforce. This study aimed to evaluate whether applying such a model in a rural, Irish setting, delivered by Assistant Psychologists could replicate such results.

Aims: To evaluate the clinical effectiveness of a primary care psychology service (Access to Psychological Services Ireland – APSI) delivered by Assistant Psychologists, in an Irish rural setting, throughout its second and third operational years.

Method: A repeated measures design was used to evaluate the clinical outcomes of service users who completed one or more brief CBT-oriented interventions within a two-year period. Psychometric measures of psychological distress (K-10), everyday functioning (WSAS), health and economic outcomes (Eco-Psy and EQ-5D-3L), anxiety (GAD-7) and depressive (PHQ-9) symptomatology were administered to service users at assessment, post-intervention and three-month follow-up.

Results: Statistically and clinically significant reductions were observed in the 567 service users who completed an intervention on measures of clinical distress, daily functioning and economic outcomes, between assessment and follow-up, for those who completed brief cognitive behavioural therapy (bCBT) and guided self-help (GSH). There were mixed results for those who completed computerised CBT (cCBT).

Conclusions: Clinical outcomes consistent with those reported by stepped care services in other predominantly urban, international settings, were achieved. The results provide additional evidence that a stepped-care, cognitive behavioural approach can reduce clinical distress for those with mild-to-moderate mental health presentations in a primary care setting.

Keywords: Cognitive behavioural therapy, Stepped care, Service evaluation, Irish, Primary Care, Assistant Psychologist

Introduction

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) has recommended the use of certain psychological therapies as initial treatments for mild-to-moderate mental health difficulties1,2. One such recommended therapy is cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for anxiety and depression. NICE also advocates a stepped care model of service provision in the management of psychological distress3. Based on these recommendations, Access to Psychological Services Ireland (APSI), was established and piloted in Roscommon, Ireland (established 2013). Key service objectives of APSI include the provision of brief, evidence-based psychological interventions in a high throughput and cost-effective service model that allows rapid access to treatment. This new service aimed to maximise accessibility by offering next day assessments to all new referrals.

APSI utilises a stepped care system, offering a suite of psychological interventions for adults with mild-to-moderate mental health presentations, including computerised CBT, guided self-help, and brief one-to-one CBT4. Service users are first provided with the least intensive intervention that is likely to bring about clinical change. The stepped care model ensures that service users not demonstrating a clinical improvement after low intensity interventions are stepped up to a higher intensity intervention.

APSI is modelled on Increasing Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT), a stepped care service developed in England and the STEPS programme developed by Jim White in Scotland5. Within this service, mental health practitioners aim to support service users’ self-management of their recovery through the provision of low intensity, CBT-based interventions along with higher intensity individual therapy. Demonstration sites in the U.K. have found good recovery rates (55-56%) for those who engaged with IAPT6. Similar results were found for APSI one year after establishment, in which 67.9% of treatment completers saw significant clinical change on measures of clinical distress. APSI Roscommon has also demonstrated significantly reduced waiting times (nine days was the median time between referral and assessment), thereby increasing access and providing early intervention for those presenting with mild-to-moderate mental health difficulties4.

The current paper evaluates the clinical effectiveness of APSI in its second and third operational years wherein a large dataset facilitated a more comprehensive analysis of therapeutic outcomes. An expansion of types of service provision provided an additional rationale for this analysis. Changes include the inclusion of computerised CBT as a form of intervention. The WSAS and K-10 were also utilised in year two to examine whether these psychometrics added value to the analysis of outcomes. By year three, the research question for evaluation broadened to not only investigating therapeutic outcomes for individual interventions but comparing these outcomes between interventions.

Method

Evaluation Design

A repeated measures design was employed to evaluate service users’ clinical, health and economic outcomes. Measures of psychological distress for year 2 included the Core – Outcome Measure (CORE-OM) and the Kessler – 10 (K-10), depressive symptomatology as measured by the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), anxiety symptomatology as measured by the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7), and everyday functioning as measured by the Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS) which were administered at assessment, post-therapy and three month follow-up. Service user health status, as measured by the EQ-5D-3L, was compared at assessment and post-therapy, and service users’ economic outcomes were compared at assessment and three-month follow-up using the Eco-Psy.

In year 3, a service review highlighting the impact of the use of extensive psychometrics on service user engagement at initial assessment led to a reduction of psychometrics at assessment to the PHQ-9, GAD-7 and WSAS. These were administered at assessment, post-therapy and three-month follow-up whilst service users’ economic outcomes were again compared at assessment and three-month follow-up by the Eco-Psy.

Service users

APSI provides treatment to adults (18+) with mild-to-moderate mental health presentations. Exclusion criteria include debilitating major mental disorders that preclude engagement in brief, self-directed work (e.g. schizophrenia, eating disorders, bipolar disorder) and/or the presence of active suicidality. Severe presentations, with or without an active risk of suicide, are referred to secondary care or other appropriate services. The nature of a service user’s mental health presentation is assessed at an initial assessment session and discussed in clinical supervision.

A total of 624 referrals were made to APSI within year 2 which increased considerably to 1,482 in year 3 (subsequent to an expansion into two further counties), equating to a total of 2,106 referrals across year 2 and 3. The number of referrals received for which service users fully completed at least one intervention were 146 in year 2 and 421 in year 3, totalling 567 interventions completed across two years. There were almost twice as many females (60.3%) that completed interventions than males (39.7%), with an overall mean age of 41.16 (SD 14.05).

Interventions

Service users were offered a range of interventions including guided self-help (GSH), computerised cognitive behavioural therapy (cCBT), group psycho-educational programmes and brief one-to-one cognitive behavioural therapy (bCBT). The cCBT programme consists of four modules delivered over 4 weeks. Using cognitive behavioural theory, the program aims to increase psychological and behavioural flexibility through modifying patterns of maladaptive behaviour and challenging cognitions. GSH involves of the provision of psycho-educational materials to inform and empower users in managing their mental health difficulties. One-to-one bCBT consists of six sessions delivered on consecutive weeks. This involves the delivery of standard CBT strategies including thought diaries, behavioural activation and cognitive restructuring. Group psycho-educational programmes consist of stress management skills workshops and wellness groups that inform service users about stress and anxiety whilst promoting self-care and stress management skills. The intervention offered was dependent upon the severity of presentation at initial assessment, consistent with NICE guidelines1,2 .

Practitioners

The service was delivered by Assistant Psychologist practitioners working in primary care team areas across the midland counties of Ireland. Practitioners had either a primary degree/higher diploma in psychology, masters in psychology, or both. Prior to delivering treatment, practitioners attended training workshops on the assessment and treatment of mental health difficulties in primary care, including workshops on delivering GSH and bCBT. This training was delivered by a senior clinical psychologist who also provided weekly group supervision.

Measures

| Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation–Outcome Measure (CORE-OM).

The 34-item CORE-OM is a measure of changes in clinical distress post-intervention. This self-report questionnaire assesses psychological distress across four domains including subjective well-being, problems/symptoms, life/social functioning and risk. The CORE-OM has demonstrated reliability (α = .94) and validity, and can be used in a wide range of mental health settings7. The clinical threshold score for the CORE-OM is 10.

Kessler-10 (K-10). The 10-item K-10 is a measure of psychological distress consisting of items relating to symptoms of anxiety and depression experienced within the last four weeks8. It has demonstrated internal consistency reliability (α = .92- .93). Those who score under 20 are likely to be in good mental health; scores over 20 indicate increased probability of a mental disorder.

Patient Health Questionnaire–9 (PHQ-9). The PHQ-9 is a self-report measure used to assess depressive symptomatology based on the nine DSM-5 symptoms of a major depressive disorder9,10. This measure has demonstrated high reliability (α = .86 -.89), sensitivity (88% -92%) and specificity (88%). The PHQ-9 can also be used as a continuous measure of depression. The clinical threshold score for the PHQ-9 is 10. |

| Generalised Anxiety Disorder–7 (GAD-7).

The Generalised Anxiety Disorder–7 is a self-report measure used to assess the seven symptoms of a DSM-5 diagnosis of generalised anxiety disorder11. The questionnaire is also suitable to screen for panic disorder, social anxiety disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder and was utilized as such. This scale has demonstrated internal consistency (α = .92) and test-retest reliability (intra-class correlation = .83). The clinical threshold score for the GAD-7 is 8.

Eco-Psy. The Eco-Psy is a 12 item self-report measure designed to assess economic outcomes associated with mental health treatment12. It consists of open and closed questions that examine healthcare utilisation, employment status and work productivity.

EQ-5D-3L. The (5-item) EQ-5D-3L is a self-report measure of overall health13. It consists of the five dimensions of mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression. Each dimension has three answer categories representing three levels of functioning.

Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS). The Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS) is used to measure everyday functioning. This self-report scale consists of five items measuring the degree to which mental health difficulties are impairing an individual’s functioning across five areas: work, home management, relationships, social leisure activities and private leisure activities. Cronbach’s alpha measures of internal consistency ranged from 0.7 to 0.94. Test-retest correlation was 0.7314. The clinical threshold score for the WSAS is 10. |

Data Analysis

Repeated measures t-tests evaluated service users’ scores on each of the clinical, economic and health measures from pre- to post-therapy, and pre-therapy to 3-month follow-up in year 2. The improved data collection methods for year 3 allowed for a comparative analysis between interventions. Mixed between-within subjects ANOVA were conducted to investigate overall change in clinical outcome across the PHQ-9, GAD-7 and WSAS psychometrics as well as examining any interaction effects. Levels of clinical recovery and reliable change in pre- and post-intervention scores on the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 were also calculated.

Results

Year Two

Referral Pathways

A total of 624 referrals were made to APSI during the second year of operation, with GP’s accounting for the majority of referrals (n = 400; 64.1%), followed by secondary care (n = 101; 16.2%), other (such as social worker; n = 63; 10.1%) and self-referral (n = 55; 8.8%).

Of the 624 referrals received, 69 service users were deemed inappropriate for primary care treatment while 134 declined treatment. A further 145 were referred on to either Counselling in Primary Care (CIPC, local counselling services; n = 117), secondary care (n = 18) or other (n = 10). Seventy-one only attended the assessment session and 55 dropped out. Insufficient data existed for 4 clients. A total of 146 completed an intervention with the service (i.e. 73% completion rate of those who commenced an intervention). Treatment completion was defined as attending all the planned sessions of the intervention. Subsequent statistics were run in this study on treatment completers only (n = 146) with separate future studies analysing the data on non-completers. The mean number of days between receipt of referral and assessment was 13.5 for those who completed at least one treatment (n = 146). Of the 146 who completed at least one intervention, the majority completed GSH, followed by bCBT and fewest engaged with cCBT. A small number engaged with more than one intervention.

Effectiveness of Intervention

Between assessment and treatment completion

Significant reductions on scores between assessment and therapy completion occurred on the K-10 and GAD-7 across all three interventions (cCBT, GSH, and bCBT). Significant reductions in scores across this period on CORE-OM, PHQ-9 and WSAS also occurred for GSH and bCBT. The mean scores for those who completed GSH and bCBT on the CORE-OM, K-10, and GAD-7 went from above the clinical threshold to below, with a similar reduction in scores occurring on the PHQ-9 for those who completed bCBT (with the mean score on the PHQ-9 for those who completed GSH already being below the clinical threshold) – see Table 1.

Table 1. Clinical outcomes of GSH, cCBT and bCBT: Year 2

Instrument(Clinical Cut-off) |

Assessment M (SE) |

Post-therapy

M (SE) |

t (df) |

||||||

| GSH | cCBT | bCBT | GSH | cCBT | bCBT | GSH | cCBT | bCBT | |

| K-10

(20) |

25.05 (1.46) | 24 (3.9) | 29.5 (1.43) | 16.46 (0.89) | 18.57 (3.53) | 20 (1.19) | 7.64* (36) | 1.79 (6) | 8.0*(33) |

| CORE-OM

(10) |

14.05 (1.12) |

– |

14.96 (1.3) | 5.09 (0.64) |

– |

7.78 (0.97) | 7.18*(17) |

– |

5.87*(21) |

| WSAS

(10) |

12.20 (1.37) | 16.17 (3.32) | 20.08 (1.72) | 6.3 (1.07) | 14.33 (4.33) | 11.19 (1.58) | 4.8*(43) | .49 (5) | 5.89*(35) |

| PHQ-9

(10) |

9.87 (0.85) | 9.86 (1.93) | 13.39 (0.99) | 4.6 (0.61) | 6 (1.38) | 6.51 (0.71) | 6.67*(62) | 3.01*(6) | 7.65*(52) |

| GAD-7

(8) |

8.6 (0.63) | 9.14 (1.58) | 12.39 (0.77) | 3.57 (0.41) | 4.42 (1.25) | 5.68 (0.61) | 8.58*(68) | 2.75*(7) | 9.75*(60) |

*p <.05.

No data available on the CORE-OM for those who completed cCBT.

Health and Economic Outcomes.

Health outcomes as measured by the EQ-5D-3L were available for service users who engaged with either GSH or bCBT. Completed GSH intervention resulted in a significant change in the domain of ‘Anxiety/Depression’ from assessment (M = 1.8, SE = .13) to post therapy (M = 1.2, SE = .13), t(9) = 3.67, p < .05. Similarly, for those who completed bCBT a significant reduction was observed in the domain of ‘Anxiety/Depression’ from assessment (M = 2.33, SE = .21) to post therapy (M = 1.33, SE = .21), t(5) = 2.74, p < .05.

Follow-Up

Three months following discharge from APSI, service users were contacted to assess their progress since completing an intervention with APSI. Significant and ongoing reductions on scores between assessment and follow-up were recorded on the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 across all three interventions (cCBT, GSH, and bCBT). In addition, those who completed GSH and bCBT recorded ongoing significant reductions on scores on the CORE-OM and K10, with the scores on CORE-OM, K10 and GAD-7 reducing from above the clinical threshold to below for these two interventions – see Table 2.

Table 2. GSH, cCBT and bCBT treatment completers: Comparison of mean scores at assessment and 3 month follow-up on the K10, CORE-OM, WSAS, PHQ-9 and GAD-7.Yr 2.

Instrument(Clinical Cut-off) |

Assessment

M (SE) |

Follow-Up

M (SE) |

t (df) |

||||||

| GSH | cCBT | bCBT | GSH | cCBT | bCBT | GSH | cCBT | bCBT | |

| K-10

(20) |

22.89 (1.49) | 24 (3.9) | 28.55 (1.86) | 15.05 (1.35) | 18.57 (3.53) | 18.39 (1.99) | 4.78*(18) | 1.79 (6) | 7.539*(17) |

| CORE-OM

(10) |

11.06 (1.85) | – | 12.53 (1.44) | 5.75 (.82) | – | 6.86 (.57) | 2.7*(7) | – | 4.21*(10) |

| WSAS

(10) |

8.86 (1.76) | 21 (4.58) | 20.86 (3.16) | 3.75 (1.49) | 20.66 (6.48) | 16.71 (3.36) | 3.21*(7) | .96 (2) | 1.43 (13) |

| PHQ-9

(10) |

8.64 (.96) | 9.85 (1.9) | 13.0 (1.36) | 4.68 (1.0) | 6.0 (1.3) | 6.96 (1.28) | 3.31*(21) | 3.012*(6) | 4.62*(29) |

| GAD-7

(8) |

8.6 (.97) | 9.14 (1.5) | 12.06 (1.03) | 4.13 (.74) | 4.42 (1.25) | 6.76 (1.09) | 4.5*(19) | 2.75*(6) | 4.39*(29) |

*p <.05.

No data available on the CORE-OM for those who completed cCBT.

Year Three

Referral Pathways and Intervention

A total of 1482 referrals were made to APSI during the third year of operation. As with year 2 referral trends, GPs accounted for the majority of referrals (n = 958; 64.64%), followed by secondary care (n = 219; 14.77%), self-referral (n = 175; 11.8%) and other (n = 130; 8.7%). Of the 413 who completed at least one intervention and for whom complete data were available at end of therapy, 66.1% (n = 273) completed GSH, 20.3% (n = 84) completed bCBT, 12.34% (n = 51) completed cCBT and 1.2% (n = 5) completed group intervention. Due to the small numbers of completers for group intervention, this cohort was excluded from the following analysis.

Comparing Interventions Across Time

Mixed between-within ANOVA were conducted to assess the impact of three different interventions (GSH, bCBT and cCBT) on service user psychometric scores across three time periods (assessment, post-therapy and three-month follow-up).

Depressive symptomatology – PHQ-9.

Impact of time and intervention

Where follow-up data was available, a mixed between-within ANOVA was conducted to assess the impact of the three interventions on service user’s depressive symptoms as measured by the PHQ-9 across the three time points. There was no significant interaction effect between intervention type and time, Wilks Lambda = .924, F(4, 202) = 2.027, p = .092. There was a main effect for time, Wilks Lambda = .509, F(2, 101) = 48.75, p <.05, partial eta squared = .491 (large effect size), with all three groups showing reductions across time indicating an overall reduction in depressive symptomatology regardless of intervention (see Table 3).

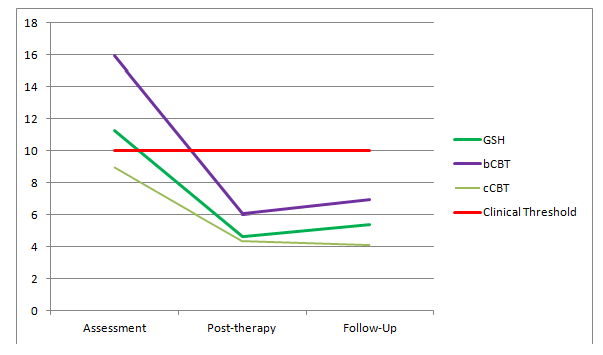

The main effect comparing the three types of intervention was significant, F(2, 102) = 3.401, p <.05, partial eta squared = .063 (moderate effect size) suggesting differences between types of intervention in reducing depressive symptoms (see Figure 1). The mean scores for the GSH and bCBT groups fell below the clinical threshold score of 10 from assessment to post-therapy and remained below 10 at follow-up. The same was not observed for cCBT as the assessment mean was below clinical threshold and remained below across time.

Figure 1. PHQ-9 Scores across Time for Each Intervention

Rates of reliable and clinically significant change

The level of ‘reliable change’ was defined in keeping with Jacobson & Truax15, and IAPT research16, as an improvement of ≥ 6 on the PHQ-9. The level of ‘reliable change’ following an intervention for clients in the clinical range, i.e. ≥ 10 on the PHQ-9 at assessment (n= 301), was 71% (n= 214). Of those in the clinical range at assessment (n= 301), 66% (N= 198) were no longer in the clinical range (i.e. PHQ-9 ≤ 9) following an intervention.

The two most commonly utilised interventions were Guided Self-Help (GSH) and brief CBT (bCBT). Of those in the clinical range who received GSH (n= 195), 73% showed reliable change (n=142), and of those in the clinical range who received bCBT (n= 78), 73% showed reliable change (n= 57) on the PHQ-9.

Anxiety symptomatology – GAD-7.

Impact of time and intervention

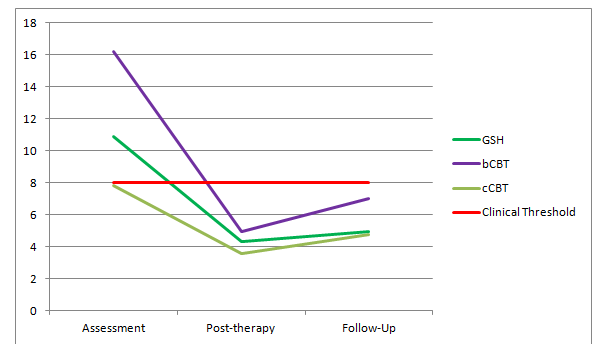

Where follow-up data was available, a mixed between-within ANOVA was conducted to assess the impact of the three interventions on service users’ anxiety symptoms as measured by the GAD-7 across time. There was a significant interaction effect between intervention type and time, Wilks Lambda = .859, F(4, 200) = 3.961, p < .05, partial eta squared = .073 (moderate effect size), indicating that the combination of time and intervention were likely responsible for any reduction in anxiety scores.

There was a main effect for time, Wilks Lambda = .474, F(2, 100) = 55.426, p <.05, partial eta squared = .526 (large effect size), with all three groups showing reductions in anxiety symptom scores between assessment and post-therapy and a slight non-significant increase between post-therapy and follow-up (see Table 3). The main effect comparing the three types of intervention was significant, F(2, 101) = 4.756, p <.05, partial eta squared = .086 (moderate effect size), suggesting differences between types of intervention in reducing anxiety symptoms (see Figure 2.). The mean scores for the GSH and bCBT groups fell below the clinical threshold score of 8 from assessment to post-therapy and remained below at follow-up. The same was not observed for cCBT.

Figure 2. GAD-7 Scores across Time for Each Intervention

Daily Functioning – WSAS.

A mixed between-within ANOVA was conducted to assess the impact of the three interventions on service users’ daily functioning as measured by the WSAS from assessment to post-therapy. There was no significant interaction effect between intervention type and time, Wilks Lambda = .997, F(2, 405) = .697, p = .499.

There was a main effect for time, Wilks Lambda = .783, F(1, 405) = 112.558, p <.05, partial eta squared = .217 (large effect size), with all three groups showing improving scores from assessment to follow-up indicating an overall improvement in daily functioning regardless of which intervention engaged with (see Table 3). The main effect comparing the three types of intervention was significant, F(2, 405) = 5.608, p <.05, partial eta squared = .027 (small effect size) suggesting differences between types of intervention in improving daily functioning. The mean scores for the GSH group fell below the clinical threshold score of 10 from assessment to post-therapy. The same was not observed for bCBT and cCBT as the mean score post-therapy remained above clinical threshold.

Table 3. Psychometric Scores for GSH, bCBT and cCBT treatment completers across three Time Periods. Year 3.

| Psychometric | Time Period |

GSH |

bCBT |

cCBT |

||||||

| N | M | SD | N | M | SD | N | M |

SD |

||

| PHQ-9 |

Assessment |

73 |

11.27 |

6.008 |

21 |

15.95 |

5.454 |

11 |

9 |

7.376 |

Post-therapy |

4.644 |

4.709 |

6.048 |

5.766 |

4.364 |

3.749 |

||||

Follow-up |

5.37 |

5.526 |

6.95 |

7.749 |

4.09 |

3.618 |

||||

|

GAD-7 |

Assessment |

72 |

10.917 |

5.373 |

21 |

16.19 |

3.124 |

11 |

7.812 |

7.547 |

Post-therapy |

4.333 |

4.162 |

4.952 |

5.454 |

3.545 |

2.876 |

||||

Follow-up |

4.97 |

5.352 |

7 |

7.321 |

4.73 |

3.636 |

||||

| WSAS |

Assessment |

273 |

15.87 |

9.611 |

84 |

18.845 |

10.19 |

51 |

17.235 |

10.483 |

Post-therapy |

9.3 |

8.603 |

13.02 |

10.976 |

12.12 |

8.657 |

||||

Rates of reliable and clinically significant change

The level of ‘reliable change’ was defined in keeping with Jacobson & Truax15 and IAPT research16, as an improvement ≥ 4 on the GAD-7. The level of ‘reliable change’ following an intervention for clients in the clinical range, i.e. ≥ 8 on the GAD-7 at assessment (n= 323), was 78% (n= 253). Of those in the clinical range at assessment (n=323), 64% (n= 207) were no longer in the clinical range (i.e. GAD-7 ≤ 7) following an intervention.

The two most commonly utilised interventions were GSH and bCBT. Of those in the clinical range who received GSH (n= 207), 80% showed reliable change (n= 166), and of those in the clinical range who received bCBT (n= 87) 75% showed reliable change (n= 65) on the GAD-7.

Economic outcomes.

Wilcoxon Signed-Rank tests were conducted to assess differences in service user economic outcomes between assessment and follow-up as measured by the Eco-Psy. There were no significant changes in number of secondary care appointments attended (Z = -1.496, p = .135) nor number of days missed at work (Z = -1.373, p = .17). However, there were significant reductions in the number of primary care appointments attended (Z = -2.295, p <.05) and the number of medications taken by the service user daily (Z = -2.54, p <.05).

Discussion

Overall, across both years of evaluation, there is evidence that APSI has benefitted many service-users in reducing anxiety, depression and improving overall well-being. The rates of clinical improvement and reliable change for treatment completers were at least equivalent to those reported in UK-based studies of stepped-care interventions. The provision of the service delivered by Assistant Psychologists did not result in any obvious deterioration in clinical outcomes. Whether a psychology background adds additional value to service provision may provide a basis for future research. Overall, these results would seem to provide an additional indication that stepped-care models using cognitive behavioural principles can be successfully applied in other international settings including services based in rural areas. Several Irish national policy documents have promoted an expansion of Primary Care services (cf: Primary Care: A New Direction17) and most specifically the increased provision of psychological therapies at the Primary Care level (cf: Sláintecare18). This research provides further evidence that such expansion is not only needed but can be successfully implemented.

Moreover, this study continues to add to and further elaborate our knowledge of how stepped-care provision is helpful to service users with mild-to-moderate levels of distress. In year two, both Guided Self-Help and brief CBT were found to be clinically and statistically significant in reducing symptomatology from assessment to post-therapy to follow-up. Furthermore, the GSH intervention appeared overall to be the most effective in reducing service-user scores on the WSAS, indicating an improvement in their everyday functioning. One possible explanation for this could be that the use of GSH materials by the service user fostered a sense of being one’s own agent of change, potentially boosting confidence for re-engaging with employment, social and leisure activities.

Computerised CBT had mixed results as not all scores on psychometrics had either statistically or clinically significant changes. There were similar findings in year three when analysis also allowed for direct comparison between interventions across time. These results indicated that those who engaged with bCBT and GSH had significantly greater reductions in symptomatology than those who engaged with cCBT. However, these findings do not necessarily suggest that GSH and bCBT are more effective interventions than cCBT. These findings may be due to the stepped-care model of the service which invites service-users with psychometric scores below the clinical threshold to engage with cCBT first. The baseline scores for service-users that engaged with cCBT were much lower and therefore remained low or showed smaller decreases than those who engaged with GSH or bCBT whose baseline scores were higher.

This evaluation presents similar findings to that of the service’s initial evaluation, which also found reductions in depressive and anxiety symptomatology following GSH and bCBT intervention4. This study also found that in year three, as in the initial evaluation, there was a significant reduction in the amount of mental health medications used by the service user. This may suggest that the introduction of brief psychological intervention could reduce the use of or reliance on medication for managing mental health symptoms. Therefore, APSI has increasingly shown evidence of providing an effective service model for treating mild to moderate mental health presentations in its first three years. What remains to be evaluated within the service model is the provision of psycho-educational groups. The scarcity of complete data for service users who engaged with groups reflects the difficulty of initial recruitment and the drop-out rate. Future studies should consider qualitative evaluations of these groups to investigate these issues, as well as clinical outcomes.

While the level of completion of the interventions of those who commenced them was high (73%), significant proportions of service users were either signposted to alternative services at assessment, or following assessment declined further intervention (with a smaller proportion dropping out mid-intervention). Further research could explore the decisions of these categories of service users in greater depth. It may be that certain service users were seeking a different type of support than that on offer, or found that following a swift response to their distress than they did not want or require further input. This may indicate that primary care psychology services that are easily accessible (with walk-in, self-referral options and low waiting times) may need to re-conceptualise themselves as engaging in psychological triage and community signposting work as much as in delivering formal psychological interventions.

Study strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study include the extensive use of multiple reliable and validated psychometric assessment tools. This ensured a comprehensive evaluation of not only service users’ presenting distress, but of more generalised functional impairment. Coupled with the iterative nature of psychometric evaluation across three time points, this resulted in a rigorous and longitudinal measure of distress. The study was limited by the modest percentage of service users who completed a full treatment, and were thus eligible for evaluation. This reduced the potential evaluative sample, limiting the data for analysis. This may have implications for the statistical significance/power of the results. Furthermore, motives for non-completion were not established and therefore, there may be a grouping bias in the presentation of those service users who completed treatment in full. As outlined above, a more extensive analysis of the data on non-completers will form the basis of additional studies.

Conclusions and Recommendations

This study provided additional evidence that a stepped-care model of psychological interventions, provided by Assistant Psychologists, can operate effectively in a rural Irish setting. Findings from the current study indicate both clinically and statistically significant changes in outcomes for service users who completed either GSH or bCBT as an intervention with the APSI service. Triangulation of data is recommended for future evaluation, targeting service users, referrers and stakeholders. This may be helpful in establishing factors relevant to non-completion or declining further intervention, efficacy of stakeholder engagement, and the service-users’ experience of the service. This type of multi-faceted analysis could also provide a more robust measurement of the APSI service, and help to continue to enhance both service delivery and clinical outcomes.

================================================================

References

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Depression: The treatment and management of depression in adults. 2009. London: Nice.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Generalised anxiety disorder and panic disorder (with or without agoraphobia) in adults: Management in primary, secondary and community care. 2011. London: NICE.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Commissioning stepped care for people with common mental health disorders. 2011. London: NICE.

- McHugh, P., Martin, N., Hennessy, M., Collins, P., & Byrne, M. 2015. An evaluation of Access to Psychological Services Ireland: year one outcomes. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine, 1-9.

- White J, Joice A, Petrie S, Johnston S, Gilroy D, Hutton P, Hynes N. 2008. STEPS: going beyond the tip of the iceberg: a multi-level, multipurpose approach to common mental health problems. Journal of Public Mental Health 7, 42–50.

- Clark, D. M., Layard, R., Smithies, R., Richards, D. A., Suckling, R., & Wright, B. . 2009. Improving access to psychological therapy: Initial evaluation of two UK demonstration sites. Behaviour research and therapy, 47(11), 910-920.

- Evans, C.J., Connell, J., Barkham, M., Margison, F., McGrath, G., Mellor-Clark, J., & Audin, K.. 2002. Towards a standardised brief outcome measure: Psychometric properties and utility of the CORE-OM. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 180, 51-60.

- Kessler, R. C., Andrews, G., Colpe, L. J., Hiripi, E., Mroczek, D. K., Normand, S. L., … & Zaslavsky, A. M. 2002. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychological Medicine, 32(6), 959-976.

- Gilbody, S., Richards, D., & Barkham, M. 2007. Diagnosing depression in primary care using self-completed instruments: UK validation of PHQ-9 and CORE-OM. The British Journal of General Practice, 57, 650-2.

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. 2001. The PHQ‐9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of general internal medicine, 16(9), 606-613.

- Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B., & Lowe, B. 2006. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166, 1092-1097.

- C., Byrne, M., & McHugh, P. 2013. ‘Show me the money’: Improving the economic evaluation of mental health services. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine, 30(3), 163-170.

- Rabin, R., & Charro, F. D. 2001. EQ-SD: a measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Annals of medicine, 33(5), 337-343.

- Mundt, J.C., Marks, I.M., Shear, M. K., & Greist, J. M. 2002. The Work and Social Adjustment Scale: a simple measure of impairment in functioning. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 180(5), 461-4.

- Jacobson NS, Truax P. 1991. Clinical significance: a statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 59, 12–19.

- IAPT, N. H. S. England. 2014. Improving Access to Psychological Therapies: Measuring Improvement and Recovery, Adult Services, version 2. Accessed at https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20160302155408/http://www.iapt.nhs.uk/silo/files/measuring-recovery-2014.pdf on 30/01/19.

- Department of Health. Primary Care – A New Direction. 2001. Dublin: Government Stationary Office.

- Houses of the Oireachtas Committee on the Future of Healthcare, 2017. Slaintecare Report.

Authors

Catherine Walshe, Ulster University.

Zara Walsh, University of Limerick.

Lisa Clogher, Roscommon Psychology Department.

Dr. Pádraig Collins, Roscommon Psychology Department.

Dr. Michael Byrne, HSE National Disability Children & Families Team.

Corresponding Author: Dr. Pádraig Collins. Email: padraig.collins@hse.ie

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the staff at APSI for their work in collecting the service data on which this evaluation is based.