Pádraig Collins and Sophie Gallagher

Abstract

This article explores the recent and significant growth in Clinical Psychology numbers in Ireland and abroad. It then explores the challenges that may exist around sustaining such growth. It also explores potential solutions to such within the context that not attending proactively to these difficulties might result in the current number of Clinical Psychologists in the Irish workforce representing the ‘high water mark’ of Clinical Psychology in Ireland.

Introduction

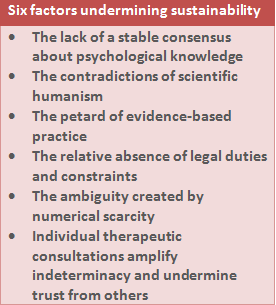

In a seminal paper David Pilgrim1 set out the “6 threats to the sustainability of clinical psychology” highlighting profound philosophical and practical threats he felt the profession then faced (see Table 1). If the growth in numbers employed in Clinical Psychology is any metric of its strength, then the subsequent decade indicated that the profession either overcame or was not impeded (at least as of yet) by such issues. The following analysis of Clinical Psychology numbers would imply, however, that Pilgrim’s warning may yet prove prescient. This paper expands on these concerns and explores those specific to the challenges of Clinical Psychology in Ireland.

The Boom in Clinical Psychology

Although exploring the reasons why Clinical Psychology might have flourished in recent times in any depth is beyond the scope of this article, the evidence of this phenomenon is presented.

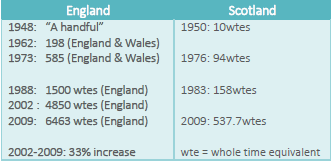

Looking at figures from England (Table 2), between the early 1960s and 1970s, the number of Clinical Psychologists employed had almost trebled, albeit from a low base. By the mid- 80s it had almost trebled again and even between 2004 and 2009 an increase of 33% is recorded. Less striking, although still significant, are the increases reported for Scotland.

Table 2: Number of Clinical Psychologists in England and Scotland until 2009 2-6

A similar phenomenon is recently seen on the island of Ireland as evidenced by the figures presented in Table 3. In Northern Ireland we see a doubling of Clinical Psychology Workforce in just over a decade. In Republic of Ireland, a near doubling of Clinical Psychology posts is reported between 2002 and 2011.

Table 3: Number of Clinical Psychologists in Northern Ireland/Republic of Ireland7-9

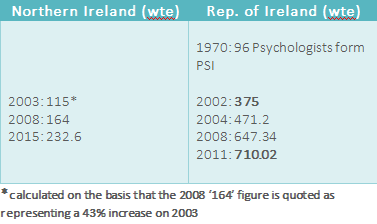

The most striking example, however, may be that in Australia (Table 4). Even in the last 7 years we see a near doubling of the numbers of registered Clinical Psychologists across Australia (registration being required to work as, and use the term ‘Psychologist’ in Australia), from a very healthy near 4000 in 2010, to near 7500 in 2016.

Table 4: Number of registered wte Clinical Psychologists in Australia 1963-201610-12

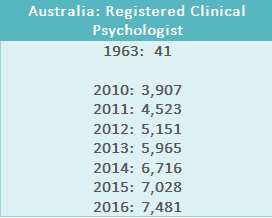

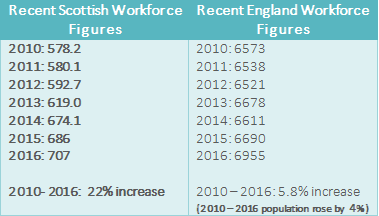

In this context it might be reasonable to think that Clinical Psychology is a thriving healthcare discipline, one that is increasing at relatively unprecedented rates and, as a profession, has little to worry about. However, more recent figures from England and Scotland presented in Table 5 indicate that there might be some grounds for concern about the future growth of this healthcare discipline.

The slowdown and evidence of ‘workforce decapitation’

Closer analysis of these figures indicate that the pace of growth appears to have slowed down internationally. While Scotland reports a still healthy growth rate of 22% between 2010 and 2016, this is a fall from the higher rates reported in previous decades. This slowdown is more pronounced in the English workforce numbers where we see growth of 5.8% between 2010-2016; barely above the level of population growth at that time (4%). Even in Australia (see Table 4), with significant increases in the number of registered Clinical Psychologists in recent decades, there is a notable decrease in the rates of growth of Clinical Psychology workforce in the most recent years. Internationally, these reductions do not appear to be explicable solely in terms of economic recession (e.g. Scotland and England had similar economic downturns but vary significantly in their workforce growth and Australia did not enter into recession).

Table 5: Recent Clinical Psychologist Workforce Figures in Scotland and England13,14

In England there are numerous anecdotal reports of workforce decapitation (which refers to a reduction in the number of senior grade posts even while the overall workforce is growing) and this concern has received some evidential support. The detailed breakdown workforce data provided by Scotland indicates that the number of consultant grade clinical psychology posts (band 8c) has fallen from 231 wtes in 2011 to 204.9 wtes in 2016 even though the overall workforce has significantly increased as per the figures reported on above. Detailed Irish data on this potential phenomenon does not appear to be easily locatable.

Lessons from history

Taking a broader socio-historical lens to understanding these phenomena we can see that many healthcare professions have similarly flourished in particular contexts but not always survived. In the 18th and 19th centuries, Lithotomists, Cataract Couchers, Herniotomists, Barber-Surgeons and Butcher–Bonesetters were flourishing healthcare professions, widely accepted as the experts in their field, largely sought after, and during certain periods, experienced significant growth in their numbers. Their ultimate demise lay not in their technology and skills being rendered obsolete by scientific advances, but rather by their roles becoming increasingly subsumed under the remit of other rising professions, most notably that of medical doctors. Historically medics would previously have shied away from this work and even included in their Hippocratic oath a commitment to leave certain interventions to more skilled professionals – i.e. “I will not use my knife, not even, verily, on sufferers from stone [i.e. kidney stones], but I will give place to such as are craftsmen therein [i.e. lithotomists]”15. However, medical guilds subsequently increasingly expanded the remit of their work and insisted that they alone could safely perform these interventions, contributing to the exclusion and ultimate demise of these previously thriving professions. Given this historic context, there may be a usefulness in exploring those issues of relevance to the ongoing survival of the profession of Clinical Psychology in Ireland.

Six Current Threats to Clinical Psychology in Ireland

When Clinical Psychology’s position in Ireland is examined, at least six clear threats to the profession’s further development may be identified.

- Isolation

Isolation may occur for practical reasons e.g. when a Staff Grade Psychologist is in position without access to the necessary support from a Senior or Principal Psychologist, or when Psychologists choose not to meet and liaise with each other on an ongoing basis. The consequences of this may be both personal and political.

While Clinical Psychology, as a profession, continues to grow, there is evidence that many of the Psychologists themselves are not personally doing so well. Detailed Irish data isn’t easily accessible but in the 2015 British Psychological Society Survey of Psychological Professionals16 (UK) 46% of Psychological professionals surveyed report depression, 49.5% report feeling they are a failure and 70% say they are finding their job stressful. Similar evidence emerged from the 2016 Unite union survey of Applied Psychologists17 with 73% reporting that over the past 12 months their morale was worse or a lot worse, and over a third seriously considered leaving their NHS posts in the last 12 months. The BPS Working Group on Health and Well-being in the Workplace18 emphasise that support from supervisors and managers is one crucial element in fostering such wellbeing.

Research from social psychology indicates that isolation can also have political consequences in that it significantly restricts a discipline’s capacity to collectively mobilise and advocate on its own behalf. Haslam et al. 19 argue that group identity not only needs to be established but also needs to be maintained by: having an awareness of the group, identification with the group, networks of contact, engaging in activities as a group, and working collaboratively for common goals19,20 . In the absence of such maintenance, group identity can atrophy. As a result, “only those that identify together can mobilize together” 21 and therefore are successful in achieving their aims.

- Relationship with New Roles

The development of new roles is inevitable in constantly evolving healthcare systems, partly due to ever increasing demands on healthcare services with limited resources. In Ireland we have seen a range of new roles emerge in the Irish Mental Health services such as the ‘Team Coordinator’, ‘Network Lead Clinicians’, ‘Recovery Lead’, ‘Peer Support Worker Coordinator’. Each of these roles can be occupied by Clinical Psychologists. Internationally we see a similar broadening and diversification in roles occupied by Clinical Psychologists including those of the ‘Responsible Clinician’, ‘Approved Clinician’ and ‘Approved Mental Health Practitioner’ in the UK. While in the USA, certain Clinical Psychologists have taken on the role of prescribing clinicians prescribing psychotropic medication.22

The diversification of traditional roles may bring with it an opportunity to reinforce or contest traditional power dynamics. Disciplines that do take up new roles have the opportunity to organisationally gain influence and those who do not may have their influence diminished. For example, the filling of the new Team Coordinator role almost universally by the nursing profession may naturally give rise to the development of team policy and team functioning that is influenced by a more bio-medical model (and nursing professional culture) rather than other influences.

- Displacement

Clinical Psychologists have traditionally viewed their role and key competencies as expert psychotherapists, as experts in psychological assessment and formulation and in governance of psychological therapies. However, other disciplines are increasingly arguing that such roles can be adequately carried out without any input from Clinical Psychology.

In terms of the training of psychiatrists and nurses, there is an explicit reference to psychological formulation being a key element in the initial and ongoing training.23,24 In terms of the governance of psychological therapies, psychiatry and nursing disciplines are very explicit they can govern and oversee the provision of psychological therapies.23,25 The Certificate in Psychosocial interventions introduced in 2013 by the Office of Nursing and Midwifery Services Director, explicitly states that all nurses should be trained up in CBT and family work to thereby lead in the provision of psychological therapies as per Vision for Change. The training is devised without any Clinical Psychology input and specifically states that trainees should have clinical supervisors while undertaking the training and these supervisors must be nurses, ideally nurses with psychosocial or psychotherapeutic training. This may encapsulate a model whereby a different discipline can be trained, governed and supervised in the provision of psychological therapy without any input from Clinical Psychology.

- Increasing Demands

The fourth threat is one that may be self-evident, that of increasing demands. There is evidence to suggest that the demands on Clinical Psychologists are constantly increasing. Over 80 per cent of Clinical Psychologists surveyed in the Unite survey17 reported that their workloads had increased either ‘a little’ or ‘a lot’ over the previous 12 months. To add to this, not only had the workloads increased in volume, but also in the diversity of need. This may partially have arisen from a more aware and empowered service-using community, increasingly cognisant of the value of psychological input, seeking input for their loved ones and themselves.

It is questionable whether the traditional model of focusing primarily on providing one-to-one therapy in consulting rooms may be capable of appropriately meeting this increased volume of need. Failing to meet this need, however, may result in the senior healthcare management querying whether Clinical Psychology, as a profession, can adequately meet the needs of the community. In this way, the ultimate demise of Clinical Psychology may lie not in the skills being rendered obsolete as such, but in the role becoming increasingly subsumed under the remit of other professions who are more accessible to the service-using community.

- Research

Research is undeniably one of Clinical Psychology’s key assets. However, less than 10% of Irish Clinical Psychologists time is spent on research (both production and dissemination).26 Furthermore, the research in which the discipline is engaged rarely attends directly to pressing concerns of healthcare managers, including those around access to services, waiting lists, standardization and quality control. Consequently, it may not be surprising that healthcare systems are not always accommodating of the wish to engage in research.

6. Service User Isolation

The final threat, and arguably the most concerning, is that of service user alienation. Ten years ago, service users felt that there was no psychology available within the state system and an individual had to go private27:

“…if I want to get a bit of psychotherapy like I go to a psychotherapist privately…because I don’t think I get that from the health service…”

A decade later, the evidence about what service users think about psychological services in Ireland is still not overly positive28:

“Wanted access to psychological services but never happened”

“I am still waiting to see a psychologist – 18 months”

In addition, service users are picking up on the interdisciplinary rivalry and the tensions this gives rise to:

“Psychiatrists and psychologists don’t listen to each other”

As mental health services are being increasingly encouraged to focus on greater service user involvement – “Nothing about me, without me” – such as the ‘Your service Your say’ HSE complaints policy29 introduced in 2015, then consequently it might be vital that Clinical Psychology is seem as an important partner in advancing the goal of greater recovery-oriented services.

A danger may lie in the profession being seen as remaining largely invisible or indifferent to long waiting lists or initiatives promoting greater recovery orientation. In such a scenario, it may be unsurprising if the service user movements ally with other disciplines to get their recovery needs met.

Six Paths to Sustainability of Clinical Psychology in Ireland

Alternatively, there may be approaches that could help the continued development and sustainability of Clinical Psychology as profession. These may include:

- Returning to the Source

Initiatives such as ‘listening exercises’ undertaken by the mental health division, and the increasing presence of ‘consumer panels’ throughout the country, may provide helpful ways to reconnect with, and learn from, the service-using community. Clinical Psychologists’ skills in qualitative methods or research may have particular relevance here. Clinical Psychologists have also been directly involved in the emergence of initiatives such as Recovery Colleges, Trialogues and peer support workers.30 In so doing Psychology is publicly seen as being on the side of greater involvement and power for service users in their own care. Such partnerships may emphasise the importance of Clinical Psychology more broadly, and not just psychological therapy, as a powerful motor of positive change.

2. From Evidence Based Practice (EBP) to Practice Based Evidence (PBE)

The second path to sustainability may involve a move from EBP to PBE. Traditionally EBP has involved applying international guidance on the use of particular therapeutic models for particular specific diagnoses. Given the critiques of the empirical validity of diagnoses in mental health30,31 and that of the limitations of the choice of therapeutic model in determining outcome32,33 it may be important that the profession returns to its empirical roots i.e. to systematically test out what is working for whom, in our own clinics, in our local area (e.g. by using standardised sessional outcome measures). Such an ongoing integration of clinical and research skills highlight the unique skill-set the profession brings to this challenging work.

Such an approach may also allow a more genuine Recovery-oriented partnership approach whereby Clinical Psychologists learn from the individual service user what specifically is helpful to them and empirically monitor where such an informed approach is truly advancing their recovery goals (e.g. whether indeed ‘returning to playing hurling’ is the key ingredient for this service user in lifting mood and thereby advancing the recovery goal of ‘feeling able to return to work’).

- Actively Exploring Ways to Help

The importance for any movement of continually ‘creating alternatives’ is well understood. From a social psychology perspective, the development of “cognitive alternatives” is absolutely crucial to change34,35, meaning if we cannot imagine alternative ways of doing things it is impossible for such alternatives to occur.

Already in Ireland there is a range of new and novel practices being engaged in, such as models of stepped care (e.g. APSI36), public engagement and community wellbeing festivals (Clonakilty and West Clare), and the concept of Recovery Colleges37 or recovery story-telling.38 Similarly there are moves towards the development of crisis houses, staffed by mental health professionals, acting as crucial places (outside of hospital settings) people can go in case of mental health crises. All of these represent novel developments for supporting people in acute mental distress. Clinical Psychologists have played a role in the establishment of these initiatives and are crucially well-placed to evaluate and thereby further promote these ventures.

4. Broadening Horizons

When we study where numbers of Clinical Psychologists continue to expand, it is often in new domains of healthcare rather than traditional ones, such as areas with a community public health focus, or the expansion of psychology within the physical health domains. One recent example is from the Cambridge and Peterborough NHS trust where the number of Clinical Psychologists in physical health domains adds up to more than all Clinical Psychologists working in mental health and primary care across the rest of the trust. Continually exploring new domains wherein Psychology can be a positive influence seems essential to the profession’s continued growth.

Similarly bringing psychological expertise into political systems (both local and national), especially in the development of national policy, allows the value of psychological work and insights to be publicly highlighted. This provides a practical and pragmatic way to use our research skills and knowledge to influence population-level change. In the UK a Behavioural Insights Team (‘nudge’ unit) was established to liaise and consult to the government on particular initiatives by applying behavioural science techniques (cf: the HPSI ‘Health and Wellbeing’ paper for a further exploration of these ideas39).

- Strategic Referencing

Progressing the values of any profession requires acquiring influence, which can be important within certain organisations, but also more broadly in influencing public opinion. In this latter regard, the profession actively seeking opportunities to form positive alliances with the media may be essential to progressing the profession’s values and beliefs (cf: David Coleman, Maureen Gaffney, Eddie Murphy).

Similarly, it may be important that the profession is not naïve about the reality of power differentiations in the management of healthcare systems, i.e. it may be important that the profession occupies senior positions in any organisation, if the values of psychology are to be promoted at the highest level.

- Reconnection

This paper commenced with the concept of isolation and the damaging impact it can have upon the discipline and on individuals. Conversely, where Clinical Psychologists find ways to reconnect with each other there lies opportunity for personal and professional strength. Research indicates that a sense of shared identity can counteract stress in the individuals themselves, as well as secure support, challenge authority and promote social change.40 Such reconnection may need to occur at a local and regional level (as well as national) with the formation of special interest groups, conferences focused on ideas of relevance to the profession, and in fora (journals, social media groups) wherein issues of relevance to Clinical Psychologists in Ireland can be debated together. If Clinical Psychologists can increasingly come together, identify together as a group, and collectively promote key shared values, then many of the threats outlined above may well be overcome and the profession’s strength continue to grow.

Conclusion

Pilgrim highlighted many potential pitfalls for the discipline of Clinical Psychology and this paper elaborates on similar threats to (and opportunities for) this profession in Ireland. The history of healthcare disciplines indicates that there were many disciplines who were flourishing in their own time, but whose demise derived from their inability to engage with social, political, and community demands that is required of all successful disciplines in this contested space of healthcare provision. A reluctance or inability in the profession of Clinical Psychology to evolve to meet these ever-changing demands may mean that we are currently observing the ‘high water mark’ of Clinical Psychology in Ireland. However, if Clinical Psychology heeds these historical warnings, it can move from potential hubris to actively reconnecting with the communities it serves and thereby vouchsafe its own future, at least for the time being.

Author

Dr. Pádraig Collins, Senior Clinical Psychologist, Roscommon.

Email: padraig.collins@hse.ie

Sophie Gallagher, Assistant Psychologist, New York, USA.

References

1. Pilgrim D. Six threats to the sustainability of clinical psychology. Clinical Psychology. 2003 Aug 28; 28:6-8.

2. National Consultative Committee of Scientists in Professions Allied to Medicine: Sub-committee in Clinical Psychology. Clinical psychology in the Scottish Health Service; 1984.

3. Management Advisory Service. Review of Clinical Psychology Services. Cheltenham: MAS; 1989.

4. British Psychological Society. Estimating the applied psychology demand in adult mental health. Leicester: Division of Clinical Psychology, BPS; 2004.

5. NHS Digital: NHS Workforce Statistics – January 2016. Accessed on 23/08/17 at http://content.digital.nhs.uk/searchcatalogue?productid=20703&q=psychologist&topics=2%2fWorkforce%2fStaff+numbers%2fNon-medical+staff&sort=Relevance&size=10&page=1%20-%20top

6. NHS Education for Scotland. Clinical psychology workforce planning group. Edinburgh: NES, Primary Care Sub-Group. 2002.

7. McCusker C, Carroll C and Laverty N. A review of the Clinical Psychology workforce in. Northern Ireland: Queen’s University Belfast, British Psychological Society. 2015.

8. Carr A. The development of clinical psychology in the Republic of Ireland. In Hall J, Pilgrim D and Turpin G, editors. Clinical Psychology in Britain: Historical Perspectives. British Psychological Society. 2015.

9. Kelly, J, Byrne, M., & Faherty, D. Heads of Psychology Services Ireland (HPSI) Workforce Planning Survey Report 2011. Roscommon: HPSI. 2012.

10. Australian Psychological Society: College of Clinical Psychologists. “History – Significant Dates in the Early History of Clinical Psychology in Australia & Internationally”. 2017. Available from: https://groups.psychology.org.au/GroupContent.aspx?ID=4384 [Accessed 30th August 2017].

11. AHPRA: Psychology Board of Australia: Data Tables November 2010. Available from: http://www.psychologyboard.gov.au [Accessed 30th August 2017].

12. AHPRA: Managing risk to the public: Regulation at work in Australia. Psychology Board of Australia. 2011-2016 Annual Report Summaries 2011-2016. Available from: http://www.ahra.gov.au. [Accessed 30th August 2017].

13. Psychology Services Workforce in NHSScotland Information Services Division Publication Report. 2016. “Table 1d: All Clinical Staff (WTE) employed in psychology services in NHSScotland from September 2010 to June 2016” accessed 31/08/17 at: http://www.isdscotland.org/Health-Topics/Workforce/Publications/2016-09-06/2016-09-06-Psychology-Workforce-Report.pdf

14. NHS Digital. NHS Workforce Statistics: Jan 2016. Staff Group, Area and Level. Available from: http://content.digital.nhs.uk/searchcatalogue?productid=20703&q=psychologist&topics=2%2fWorkforce%2fStaff+numbers%2fNon-medical+staff&sort=Relevance&size=10&page=1%20-%20top [Accessed 31st August 2017].

15. Hippocratic Oath. Available from: https://www.nlm.nih.gov/hmd/greek/greek_oath.html [Accessed 19th October 2017].

16. British Psychological Society and New Savoy staff wellbeing survey. 2015. Available from: http://www.bps.org.uk/system/files/Public%20files/Comms-media/press_release_and_charter.pdf [Accessed 30th August 2017].

17. Unite union survey of Applied Psychologists. 2016. Available from: http://www.unitetheunion.org/news/psychologists-survey-highlights-nhs-mental-health-funding-crisis/ [Accessed 30th August 2017].

18. British Psychological Society Working Group on Health and Well-Being in the Workplace. Available from: https://www.bps.org.uk/system/files/user-files/Division%20of%20Occupational%20Psychology/public/rep94_dpx.pdf [Accessed 19th October 2017].

19. Haslam SA, Reicher S. Stressing the group: social identity and the unfolding dynamics of responses to stress. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2006 Sep; 91(5):1037.

20. Tajfel H. Interindividual behaviour and intergroup behaviour. Differentiation between social groups: Studies in the social psychology of intergroup relations. 1978; 27-60.

21. Reicher S, Haslam SA, Rath R. Making a virtue of evil: A five-step social identity model of the development of collective hate. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2008 May 1; 2(3):1313-44.

22. American Psychological Association. Recommended postdoctoral training in psychopharmacology for prescription privileges. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. 1996.

23. Psychology Services Workforce in NHS Scotland Information Services Division Publication Report. 2016. “Table 1d: All Clinical Staff (WTE) employed in

College of Psychiatrists in Ireland: Curriculum for basic and higher specialist training in psychiatry. July 2016. Available from: http://www.irishpsychiatry.ie/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Curriculum-for-Basic-Higher-Specialist-Training-in-Psychiatry-July-2012-Revision-5-July-2016-21.07.16.pdf [Accessed 12th September 2017].

24. Crowe M, Carlyle D, Farmar R. Clinical formulation for mental health nursing practice. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. 2008 Dec 1; 15(10):800-7.

25. Health Service Executive (HSE) & Office of the Nursing and Midwifery Service Director, HSE. Certificate in psychosocial interventions, programme descriptor for registered nurses and midwives. Dublin; HSE. 2013.

26. McHugh P, Corcoran M, Byrne M. Survey of the research capacity of clinical psychologists in Ireland. The Journal of Mental Health Training, Education and Practice. 2016 Jul 11;11(3):182-92.

27. Mental Health Commission. A Qualitative Analysis of Submissions to the Mental Health Commission on the Discussion Paper: A Vision for a Recovery Model in Irish Mental Health Services. 2006.

28. HSE Mental Health Division. Report on the Listening Meetings. 2016. Available from: http://www.hse.ie/eng/services/list/4/Mental_Health_Services/advancingrecoveryireland/ [Accessed 31st August 2017].

29. Health Service Executive. “Your service your say”. Available from: http://www.hse.ie/eng/services/yourhealthservice/feedback/Complaints/Policy/complaintspolicy.html [Accessed 19th October 2017].

30. Timimi S. No more psychiatric labels: Why formal psychiatric diagnostic systems should be abolished. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology. 2014 Dec 31;14(3):208-15.

31. British Psychological Society: Division of Clinical Psychology Position Statement on the Classification of Behaviour and Experience in Relation to Functional Psychiatric Diagnoses. May 2013. Available from: http://www.bps.org.uk/system/files/Public%20files/cat-1325.pdf [Accessed 31st August 2017].

32. Wampold BE, Imel ZE. The great psychotherapy debate: The evidence for what makes psychotherapy work. Routledge; 2015.

33. Laska KM, Gurman AS, Wampold BE. Expanding the lens of evidence-based practice in psychotherapy: a common factors perspective. Psychotherapy. 2014 Dec;51(4):467.

34. Tajfel H, Turner JC. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. The social psychology of intergroup relations. 1979;33(47):74.

35. Reicher SD, Haslam SA, Smith JR. Working toward the experimenter: Reconceptualizing obedience within the Milgram paradigm as identification-based followership. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2012 Jul;7(4):315-24.

36. McHugh P, Martin N, Hennessy M, Collins P, Byrne M. An evaluation of Access to Psychological Services Ireland: year one outcomes. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine. 2016 Dec;33(4):225-33.

37. Perkins R, Repper J, Rinaldi M, Brown H. Recovery colleges. ImROC (Implementing Recovery through Organisational Change) Briefing Paper One. Centre for Mental Health and NHS Confederation: London. 2012;1.

38. Watts M, Downes C, Higgns A. Building Capacity in Mental Health Services to Support Recovery. An exploration of stakeholder perspectives pre and post intervention. 2014. Available from: http://www.lenus.ie [Accessed 30th August 2017].

39. Byrne M. Psychology briefing paper for the HSE Health and Wellbeing Division. 2016.

40. Haslam SA & Reicher SD. When prisoners take over the prison: A social psychology of resistance. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2012; 16(2):154-179.