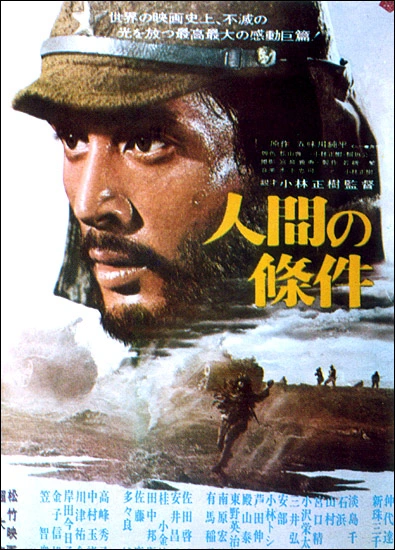

#3 in my ranking of Masaki Kobayashi’s films.

All filmed at once and released over a period of three years, The Human Condition is the Japanese, arthouse version of The Lord of the Rings or Manon of the Source, a single film production broken up into multiple parts for release reasons (who’s gonna sit through nine-and-a-half hours at once?). The second part continues the main character’s journey downward from a suited up bureaucrat in a corporate office to almost an animal by the end of this, his time in the Japanese army in Manchuria as Japan is steadily losing the overall conflict on both sides, from America at the Pacific and from the Soviet Union on the land.

Kaji (Tatsuya Nakadai) is in basic training at a remote military installation near the front against the Soviet army. He is under suspicion, meaning that he receives informal harsher treatment and won’t be on the promotions list, just like Shinjo (Kei Sato), a three-year recruit that has accusations over his head that he is a communist because his brother wrote in a communist paper. The two have become friends, isolated from the rest of the unit, but Shinjo is kept busy by their commanding officer Warrant Officer Hino (Jun Tatara) to the point where they simply don’t have enough time for any kind of plotting. Otherwise, Kaji is a good soldier. He’s a quality marksman, and he does what he can for the struggling members of the unit, in particular Obara (Kunie Tanaka), a bespectacled young man whose wife and mother-in-law are always fighting back home.

The trials and tribulations of a Japanese soldier at the tail end of World War II are not exactly the stuff of American cinema depictions of American military basic trainings. There’s a whole lot more corporal punishment meted out all of the time for the slightest of infractions. The opening scene of the film is actually the unit being awoken in the middle of the night, forced to line up, and the officer in charge slapping every single one of them because a cigarette butt was found in the drinking water. Obara was in charge before lights out, so he is blamed. Kaji comes to his defense with his own witness testimony that everything was in order when Obara was relieved, evidence that heavily implies that it was an officer patrolling around the barracks that flicked the cigarette into the water, but the officer will have none of it. Punishment will be meted out to the junior recruits with the veterans looking on from their bunks up above.

This period in basic training really is a transitional period for Kaji, between the remnants of the civilized world and the harsh wilderness and savagery of life on the battlefield, so it seems appropriate that he gets one final moment with Michiko (Michiyo Aratama), his wife, who comes to the remote training ground and is granted one night with her husband in the storehouse. Their night is his last grasp of love before he must go to the front, and it’s painful. They love each other deeply, and there seems to be little hope that they’ll ever meet each other again.

The recruits’ graduation is a long march, and Kaji does everything he can to help the exhausted Obara to finish it. He takes half of his pack on his own back and carries Obara’s rifle, but Obara still cannot finish, eventually picked up by the cart picking up the stragglers (there are three total). The veterans in the training corps, led by Yoshida (Michiro Minami) then humiliate those who couldn’t finish, most particularly Obara, which sends Obara into a spiral that ends with him committing suicide. His suicide scene ends up being incredibly sad, not just because he loses hope and decides to end it all with a rifle in the latrine (echoes of this definitely end up in Full Metal Jacket), but because he fails several times and then decides that it’s a sign that he should continue on before the gun suddenly goes off. It’s tragic in a way, and emblematic of how hard it is to find one’s humanity in a system like this.

That extends to Kaji’s reaction to Obara’s suicide. He wants the offending veteran punished, but the command structure will not allow it. They use a variety of excuses, from Kaji having a personal vendetta to everything being hearsay, but they will not allow the punishment of the perpetrators. Kaji can only stew in his own anger at the injustice as the Japanese military refuses to do anything about it. When the unit is moved towards the border, things gain a different character. It almost becomes wistful as a gap forms between basic training and actual combat, with the border (presumably the border with the Soviet Union) just on the horizon, with promises of freedom for the individual (said by Shinjo, communist, so…eh, it’s about the promise not the reality). During an emergency, Shinjo runs towards the border, deserting, and both Kaji and Yoshida run after him with Kaji knocking Yoshida into quicksand, unable to save him. He accidentally kills someone. The humanist who threw his whole life away to save some prisoners of war accidentally kills a man.

That’s the end of Part 3. A lot of events in these films, and yet because they’re all so tightly focused on Kaji himself and his emotional journey, it never feels like a jumble. There are a handful of small scenes without him (between a couple of superior officers, for instance, who talk about how his guts show that Kaji should remain on the promotions list), but even those scenes outside of his view are all in service of him. Even poor Obara’s suicide feeds into Kaji’s overall journey (sorry, Obara, this ain’t your movie).

Part 4 moves the action to near the border where the unit goes in for artillery training, led by a friend of Kaji’s from the civilian world (whom we saw briefly at the start of Part 1), Kageyama (Keiji Sada). Kaji gets the ranking of Private First Class and is put in charge of the barracks, giving him a chance to implement his humanist labor policies one more time, focusing on his fellow rookies. It all falls apart again in relatively the same fashion with human nature from outside the small group putting pressure on the inside until they crack. His ideals meet the real world and survive for a little while until they begin to fall apart as human nature intervenes over time. To relieve some of the tensions in the camp, Kageyama sends Kaji and most of the rookie soldiers out to build fortifications, during which the Russian campaign into Manchuria begins. Kaji’s little unit is folded into a new one, and they are the second line of defense after the first line further up dies gloriously for the Japanese Empire.

And here, about six hours into this war epic, do we get our first battle. From a technical point of view, the battle is competent and small in scale. It’s remarkably tense, though, and that has almost everything to do with the extraordinary amount of work that went into building Kaji as a character. There are about a dozen tanks, but the extras seem a bit thin. Still, it’s easy to see what’s going on and watch as the action moves around, and the action does no move in Japan’s favor. In the end, Kaji must pick up his gun and fire into the coming soldiers. Did his bullets hit and kill the men we see? Can we be sure in the hail of millions of bullets? We can be sure of the post-battle moment when Kaji has to strangle a fellow Japanese soldier to keep him quiet that he killed him, though. The humanist has become an outright murderer. Surely there’s no more for him to fall. We may find out in Parts 5 and 6.

Much like the first part, The Human Condition: Part II really could stand on its own. Kaji has his ideals and his journey (it’s downward, if you hadn’t surmised), and his time in the regular army has a clear beginning, middle, and end. And that journey is involving and surprisingly crushing. Watching an idealist in the middle of his ideals crashing around him to the point that he has to violate them all is really sad, and the subtext of both Kobayashi and Junpei Gomikawa’s own views in relation to the trajectory of Japan through the 30s and 40s (they were against the militarism and colonization of Manchuria) gives it an extra flavor.

This may be the middle third of a three-part tale, but it’s a great one.

Rating: 4/4

Quick note, as I have a lot to say about this three part movie, but I want to re-watch it before I blather on…just hard to find time for 9 hours of Japanese drama here at home.

BUT…there is some odd alternate history here. The fighting in Manchuko in WW2 was entirely against the Chinese, not Russians, until August 1945, mere days before the war ended. The Russians did indeed invade in a huge way (Koybayashi spending time in a Soviet POW camp of course) but after Nagasaki , and the surrender, they were mostly picking up pieces and gobbling territory…and providing support for Maoist communists.

More to come, this week or next, but wanted to put that out there early.

LikeLike

If I had to make a guess as to the change from Chinese to Russian forces, it’s potentially two-fold. First, the timeline is never that clear in this film beside the occasional reference to world events, so it could be happening in the very last days. Also, it clarifies the enemy as the Soviet Union, which is important for the final section.

LikeLike

On rewatch, this barely feels like a continuation of the first movie. Kenji’s character has changed so much, I feel like I’ve missed an entire movie. There is barely any sign of Kenji the Humanist, who defied the Kenpeitai military police. Already here we have a beaten down man just clinging to logic, morality and humanity (and he has so, so much further to fall, sadly). I will say I don’t see any indications that Kenji is a pacifist. He doesn’t even act anti-war, honestly. He’s just anti-abuse. In fact, he doesn’t ‘accidentally’ kill Yoshida, he deliberately body checks him into that pool. He also falls in himself. Twice. He DOES attempt to save Yoshida…but only after he extorts a promise from him that he’ll confess. Which doesn’t work as Yoshida dies from hemmoragic fever (ick). But that is not the same character we saw in part 1, this really feels like a separate movie in a way that the Lord of the Rings trilogy did not.

While in the first movie, in a weird way, I didn’t dislike most of the characters – here just about every Japanese soldier is an asshole. Criterion likes to really push Koybayashi as being ‘against the system’, and I don’t think that’s accurate. He is clearly against the Japanese Army (rightfully so) but what he really seems to be against is the abuses of authority in Japan. It’s an condemnation, in general, of human nature and in specific of the Japanese Army in this film.

I still utterly love his attention to detail, not just in sets and costume, where are flawless but in dialog and culture. The army recruits all act like army recruits, you have the squad clown, the bullies, the studs and those just trying to muddle through…and Obara the fuckup. More about him in a moment. I know just enough about the history and Japanese military service (with a smidge of personal experience though mine was ROTC and Field Training) to recognize when things feel off. And there’s almost none of that here. The characters don’t just look like Japanese Army, they act like it. Down to the physical brutality (‘feet apart, grit your teeth’!) but also the way a good recruit is secretly protected and a bad one…well, he’s dropped.

I have to also comment on Kenji’s wife just showing up during basic training. I can’t imagine that happening or it being tolerated but…I check and it did happen to other recruits and they didn’t put her ass back on a train immediately for some reason. That is one of the only bright spots of this movie, but even that is ‘horrible and wonderful’ as Kenji says. The moment when she strips naked for him and poses, with tears on her face (the Japanese have weird, weird hangups on nudity. They have co-ed bathing in some places but getting completely naked even for sex is ‘twisted and perverse’. It’s weird). But having his wife show up just makes everyone even more abusive towards Kenji and….yeah, I can kinda see why.

Just like I can see why Obara got abused, albeit there is no justification for trying to punk him out and make him act like a geisha (I have more true tails about the Japanese military and…that sort of thing that I will spare you from. For now). But Obara is just a load. He can’t fight, he’s not smart, he breaks things, forgets things, he’s weak, he’s a quitter, he whines. He literally would be a burden at best and get men killed at worst (as mentioned in the shooting range scene). He should be RIF’ed out or put onto some useless role peeling potatoes or something. He even screws up killing himself AND screws up not killing himself. He’s nothing. Just…a man. A human. A divine spark. And I’m surprised that Kenji only seems to pick up that Humanist torch a little and only after he killed himself.

Gah, all this and I’m barely through talking about half the movie! I will say I enjoyed the second half a bit more than the first, just because there’s less misery and less room for abuse once the war is at hand. Again, this takes place somehow around Yalta in 1945…which makes me wonder how we jumped from 1943 to 45 but…anyway.

It’s a Great film, it really is. But not a happy one. Perhaps it needs to be a tragedy but I don’t like tragedies. This is well made, though, very much so. And I don’t regret watching it again, I admire competence above all other things, I guess.

LikeLike

I don’t think the jump is that much, though there is something of a jump. The first film provides the jumping off point, though, with the execution, the failing point of his entire endeavor to make other people’s lives better with his ideas. It fails, and he ends up more focused on himself and his wife, his last 24 hours of freedom will be with her.

His action that led to Yoshida’s death really did feel like an accident to me. He body checked him because he was going to kill the other soldier. His intention was to prevent the shooting first and foremost. Getting him into the bog wasn’t intentional, and then, in a panic, he’s both trying to save Yoshida and extract the promise out of him. He’s not thinking or acting clearly, but it doesn’t make the act itself intentional.

Obara pretty simply shouldn’t have been in the military, but I think the point was that Japan wouldn’t allow it. Everyone went into the meat grinder whether they could take it or not, and the only way out was death. That’s where I find the tragedy. Yeah, he was a screw up and a load on everyone else (especially Kenji who took on that load of his own volition), but Obara’s fate was simply the result of a small unjust decision in the middle of an unjust war.

And yeah, the “fight against the system” is generic to the point of inaccuracy. There’s a very specific strain of power he’s targeting, and it’s not a general system. It’s specifically the Japanese system in different forms. He was a socialist who probably would have noted his opposition to post-war Japanese capitalism, but his opposition to things was specifically to the nationalistic aspects of these things as distinctly Japanese institutions. He was a Japanese man who took his Japaneseness seriously and saw little that he actually liked. It feels like a frustrating place to be.

LikeLike

He does have that great line he hands Kenji, which I can’t quote from memory exactly, about flowers seeming to bloom brighter in other pots…but you need to stay in your own pot where you belong.

Likewise, he has Kenji questioning if life really would be better in the USSR as a Japanese deserter

I think Kobayashi loved Japan, but he was willing to hold up a mirror to it.

LikeLike

The positive thoughts for the USSR continues for far longer in the third part than I would have expected.

LikeLike