This article is the third in a three part series dealing with the three types of female heroines available to writers. Parts One and Two may be read here and here.

Adding to the conversation on “How Do You Create Strong Female Leads,” ridersofskaith posted this insightful comment: “the Strong Female Character (TM) is someone who is Emotionally Self-Sufficient and Resilient. She can be passive, she can be a warrior, she can be a damsel, she can be someone who does nothing other than weave in a tower – as long as it’s something she chooses to do, understands, bears the consequences of, and does not regret it…because it was her doing to begin with.”

Riders hit the nail on the head. Going back to the articles posted during the last two weeks, it is possible to see that the heroines we have reviewed each have some degree of emotional independence and resilience. Heroines who have lost/sacrificed a feature of their femininity absolutely need to be self-reliant in order to enter and excel in their combat careers. In the case of the heroine who is ennobled and strengthed by the man she loves at the same time he is ennobled and strengthened by her, she may already be emotionally self-sufficient. However, it is just as likely that this type of heroine has allowed her sense of independence to devolve into the handicap of conceit, or that other factors outside her control have weakened her self-confidence. These women occasionally require outside help to realign their perception of themselves and reality.

None of this makes the heroines from Category Two feeble protagonists. Everyone has flaws, and/or their judgement is clouded occasionally. The women we discussed last week have faults, but so do their men. It is through criticizing one another that they come to recognize and then work to correct these flaws. In this way they become better people, just as we in “real life” often receive advice that will (hopefully) aid us in improving ourselves.

By this roundabout method, we come to the final category of female lead, The Passive Heroine. Before we discuss viable models of this heroine type, the term “Passive” must be clarified, as this word tends to imply weakness, lethargy, or a “[lack] in energy and will,” to quote the ever-helpful Merriam-Webster Dictionary. We will start with what the Passive Heroine is not. She is not a giddy, feather-brained damsel; neither is she a weak, timid girl who faints when threatened. The Passive Heroine is not indolent, nor is she a physically inactive participant in the story. And she most certainly is not a mere prop or prize for the hero to win.

Comparing her with her dark counterpart, the Femme Fatale, will give us some insight into what the Passive Heroine actually is. Looking at the description of Delphine Yant in the article on villainesses, we find that the Femme Fatale typically has an innate hatred for mankind. The Fatale wants to be insulated from the world so that she will not have to deal with society at large or individuals in particular. This is why she uses and abuses her femininity to murder others; it reduces the number of people she has to worry about encountering or “crowding” her life and “her” world.

On the other hand, the Passive Heroine may be defined as a woman who embraces her femininity wholeheartedly. She loves others in general with true charity. The Passive Heroine also possesses the virtues of independence, compassion, loyalty, humility, intelligence, and courage. Though this type of female protagonist usually has no skill with weapons and avoids entering combat as a warrior, she possesses deep reserves of emotional strength and resilience. For the most part, these are shown by her strong romantic ties with the hero of the tale in question.

None of this prevents her from being the driving force behind the story’s plot, future writers, because her lack of physical prowess in battle does not make her defenseless. Nor does it lessen her fortitude in the eyes of the male protagonists or the audience. While as a rule she does not fight, it is almost always clear to the audience that she is the hero’s mental and spiritual equal.

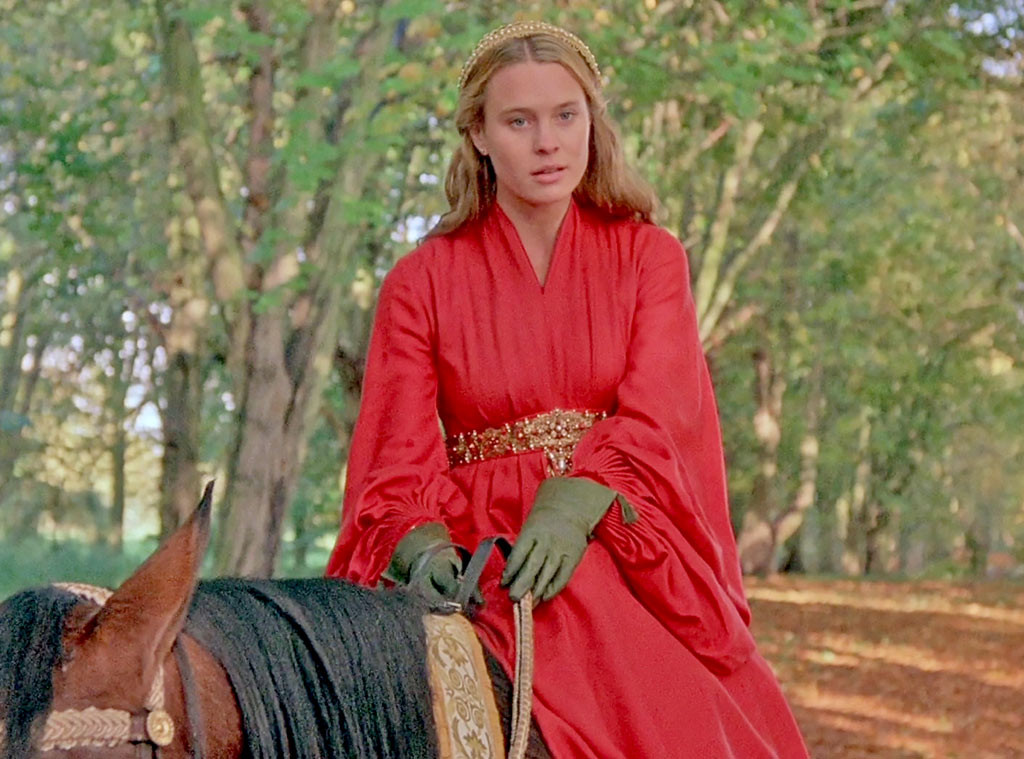

Our first example of this kind of heroine is Buttercup from The Princess Bride. Without actively intending to, Buttercup sets the entire chain of events in the film in motion. Although she begins her relationship with Westly by tormenting him, eventually, the Princess Bride falls deeply in love with the farm boy. Despite the fact that she never physically engages her enemies, Buttercup is not viewed by the audience as a weak character. How can they think this, however, since she does not duel Inigo, struggle with Fezzik, or so much as strike the much shorter Vizzini? The reason why viewers admire the Princess Bride and consider her a strong female character has less to do with her inability to bodily rebuff her captors than it does with the virtues she displays during the story.

Though her attempt to escape Vizzini’s ship almost ends in death, it is an act of courage on her part. Meanwhile, her persistent warnings of the dire punishment her captors will face if they do not release her show her intelligence; criminals usually hate to jeopardize themselves more than is necessary. By constantly reminding them of their danger, Buttercup obviously hopes to demoralize and distract her enemies. This would slow the men down, giving her the chance to escape or allow her rescuers a chance to catch up to them.

Later on, when verbally sparring with Prince Humperdink, she exhibits the benefits of all the passive virtues. The Prince’s attempts to frighten and browbeat her do nothing to shake or destroy Buttercup’s loyalty, courage, humility, independence, or love. Unlike the moment where she turns aside to avoid the Man in Black’s slap (which he restrains), the Princess never flinches away from Humperdink during these confrontations. She stands straight, meets his gaze, and holds her ground. And she does all of this without raising a hand, a sword, or some other weapon against her enemy.

Another heroine in this category is Dorothy, from The Wizard of Oz. Though she is not possessed of a romantic love interest, this Passive Heroine demonstrates great filial affection for her aunt and uncle, along with an intense devotion to her dog, Toto. In addition, during her adventure in Oz she exhibits the Passive virtues of compassion, loyalty, honesty, humility, and intelligence. Throughout her quest she also acquires the qualities of courage and emotional strength.

Her virtues appear early in the adventure when she aids the Scarecrow and the Tin Man. She does not do this out of an obsequious desire to shift responsibility from her shoulders but because it is the right thing to do. This impresses her new friends, motivating them to ask permission to travel with her. Her inner grace and beauty inspires them to be worthy of her regard, which is why both the Scarecrow and the Tin Man make light of the Wicked Witch’s threats against them, insisting that they will stay by Dorothy’s side come what may.

Regarding her third companion – the Cowardly Lion – she not only encourages him, she grows to be a better character because of him. When the Lion chases after Toto, Dorothy strikes him for scaring her dog, demonstrating a newfound and reckless courage. In a previous effort to save Toto’s life, she decided to run away from her troubles rather than stand up to them. In Oz, she impulsively reverses her decision, shown when she hits the Lion for his craven act. Her audacity shames him at the same time it leads him to admire her, and this is why the Cowardly Lion chooses to journey to Oz with Dorothy and the others. Learning from her example, for love of Dorothy he faces the Wicked Witch of the West despite his fear of her.

This is the most aggressive action Dorothy takes in the entire film. It is a gesture more of defiance than it is a substantial combat maneuver; any child of five could have hit as quickly and as hard. Compared to the more active fighting roles embraced by the women mentioned before, Dorothy does nothing remarkable here. Yet this is precisely why the scene is so memorable; standing alone and defenseless against an (admittedly timorous) Lion, this mere girl shows bravery by angrily striking out to protect one she loves.

Clearly, the Passive Heroine is not the straight-laced damsel many assume her to be. Looking at Anne Elliot from Jane Austen’s Persuasion, however, appears to reinforce the illusion that this type of female lead is a pushover. While Anne does begin the story as her family’s doormat, she does not remain in this position. Pushed around and “persuaded” by everyone she knows, eight years ago Anne allowed this compulsion to compliance to lead her to reject a marriage proposal from the man she still loves, Captain Frederick Wentworth.

So when Wentworth arrives in town some time after the film begins, he is still smarting from her rejection. In order to avenge himself on Anne, for the first half of the story Wentworth appears to actively court a younger woman, ignoring his old flame as much as propriety permits. Anne appears to take this abuse in a timid fashion, unlike Austen’s other heroines. She does not confront Wentworth or go out of her way to engage him in conversation. Rather, Anne accepts his attitude and does nothing overt to convince him to change his conduct.

His behavior, however, inspires her to exercise the passive strengths of a stalwart will, emotional self-reliance, and moral courage. Her growth here is slow, but this does not lessen its impact. If anything, it lends her extra strength; when her father demands that Anne give up an appointment with an old school friend in order to appear before a rich relative, she does not meekly obey him, the way she has previously. Instead, Anne openly refuses to cancel her scheduled visit. She goes to see her friend as promised, leaving her infuriated family to do what they please.

Her compassion for her friend, who is an invalid and housebound, combined with her loyalty to her old acquaintance, provides force for her refusal. Shortly after this, Anne’s new will power combines with her intelligence when her younger cousin begins courting her. Sensing something is “off” about his attentions, she repeatedly rebuffs his suggestion of marriage – along with the urging of her relatives and friends to accept his proposal in order to heal old family wounds.

It is worth reiterating that Anne accomplishes this without engaging in any kind of physical conflict. She does not do battle with barbed compliments or artful jibes either, as Jane Austen’s other female leads do. No, Anne wins her freedom from her family by quietly embracing her independence and the power it gives her. This is shown when she accepts Wentworth’s public proposal of marriage at a social function, to the effrontery of her confused and embarrassed family.

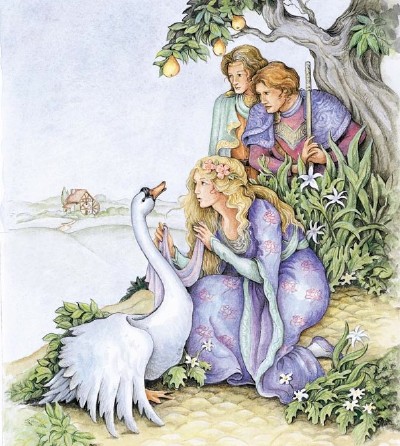

Our final example in this category is from a fairy tale that both Ridersofskaith and I enjoy: The Wild Swans. As is the case in many fairy tales, the father in this story remarries after his first wife dies. His new wife, jealous of his love for the thirteen children he had by his dead queen, turns the twelve older boys into swans. Though she tries to harm her step-daughter, Eliza, her efforts here fail due to the girl’s grace and goodness. Eventually, she forces the princess to leave the kingdom, and the girl goes out into the world to locate and free her brothers.

After finding her brothers, Eliza learns in a dream that the only way to free them is to sacrifice something she loves dearly – the roses she has enjoyed and admired from childhood. Using these, she must make shirts which will break the curse and return her brothers to their natural form. But there is a catch; it will take Eliza some time to make twelve shirts from the roses. If she accepts this task, she cannot speak until the shirts are finished. One word from her before they are complete will kill her brothers. Despite this heavy price, Eliza undertakes the mission, indicating clearly that she possesses the passive virtues of compassion, loyalty, humility, and courage.

Later on, a woodcutter and his wife discover the princess and insist she come to live with them. But when Eliza runs out of roses, she has to cut some from her kind hostess’ prized bushes in order to continue her work. Because she must remain silent, she cannot explain the matter when confronted about the “theft,” and only the arrival of the nation’s king saves Eliza from the poor woman’s furious retaliation. Instead of easing her mission, the princess’ life is made more complicated after this by her marriage to the king. While he allows her to continue making the shirts and she truly loves him, Eliza has to stay silent when suspicious members of the court accuse her of witchcraft, going so far as to falsify evidence against her.

Taken to be burned at the stake as a witch, while the citizens jeer and spit on her, Eliza silently continues weaving the final shirt for her twelfth brother. In the veritable nick of time, the swans arrive to try to save her. With the twelfth shirt mostly complete and all their lives on the line, Eliza throws them over her brothers. The twelve are immediately turned back into men and explain everything to the astonished people as their exhausted sister faints. Throughout these ordeals, Eliza exhibits not only the previously listed passive virtues, but emotional strength and resilience as well.

We can see here that Passive Heroines are, in reality, anything but demure. They are not the weakest form of female lead; though they may need to grow in certain areas, these women do not have to enter combat to make a difference in their respective worlds or to set their stories in motion. They “move mountains,” as it were, simply by accepting their feminine nature and letting it shine through their actions.

Whether your female lead is Passive or not, future writers, remember that any one of these heroine types will impress your audience as long as you respect her. Combining aspects from all three categories in the one character is also a viable option, though it is not pursued frequently. In the end, for your story to work it may be that the heroine’s femininity is what is absolutely necessary for good to win the day. That’s something to celebrate.

So, future writers, how about you shut down this link to work on your own delightful heroines? 😉

A fantastic end to a fantastic series. Great examples! These are all great reference points for future writing. Thank you for this.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re welcome! I’m glad you enjoyed them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Shut down the tab….and flap away into the sunset, as it were?

Seconding what Alex-amatopia said. This was a fantastic series of posts–thanks for setting down in plain words what it’s so hard to say simply!

LikeLiked by 1 person

😄 Good one, Riders! I’m glad that you and Alex liked the articles so much. They were a lot of work, but they were worth it. Thanks for letting me know how much they helped!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I can’t comment on the last one, but I fully agree with all of your picks; in fact, I would go so far as to defend Anne Elliot against the charge of being a doormat for her family at the beginning.

The movie certainly makes it appear as if she silently and without efforts to amend endures the mistreatment of her family. But the book makes clear that she does indeed make constant attempts to improve all of her family, defend them from harm, and use her estimable intellect to better her own position–not at the detriment of others, but to better be able to help them. She is not only a model of familial forbearance, she is a model of a woman who, in spite of having suffered ills at the hands of the man she loves, loves and cares for others out of both duty and care.

I don’t even think she was a ‘weak’ woman in regard to her having been talked into rescinding her acceptance of Captain Wentworth’s proposal. She was, as she often does in the book at least, submitting to properly constituted, well-intended authority and reason; she even submits to the morally acceptable but NOT well meant requests of authority. This is hard, especially for the ears of modern and post-modern people (not that I am saying you are either), but legal authority on Earth–while corrupted by Satan and occasionally needing removal by others–is there as an instrument of God, allowed for the common and greater good. This is obvious when we like the authority, such as when Marianne gives way before her sister out of familial duty in Sense and Sensibility, but is true so long as the authority is not contradicting the moral (natural) law or exceeding its legal bounds.

Anyway, I liked the post. I liked all of your choices. Sorry to pontificate, but I think Anne Elliot is too often unjustly maligned… just like she is in the story. I realize that was not your intent, but your choice of words caused me to need to say something about the matter.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow! Thank you for this thought-provoking and highly instructive comment, Aether! I am glad you enjoyed the post so much.

I have only seen Persuasion, not read the book (yet), which is part of the reason why I described Anne as I did. Clearly, this is an oversight that needs to be rectified.

However, you do make an astute observation. It is easy, in this time and place, to forget that obedience to lawful authority in all that is not sinful is a great virtue. Let this saying not be too hard for those who hear!

You are completely correct in describing Anne’s behavior this way, and I thank you for this. I will bear it in mind for my heroines and future articles.

LikeLike

I have watched the movie much more recently than I have read the book, but just as with every Jane Austen adaptation I have seen, the movie only underscores how good the source material is. I like most of the adaptations I have seen (except for the most recent Pride and Prejudice movie adaptation by Hollywood), but so far none of them compare very favorably with Austen’s work, and Persuasion is probably my favorite. Sorry if I came on a little too intense about it.

LikeLiked by 1 person