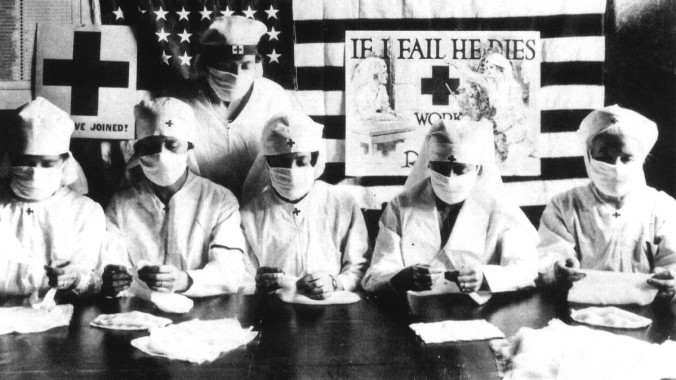

Above: Red Cross nurses show how to wear masks in fall 1918; Alma Record advertisement about coughing and sneezing; Quarantine in Alma.

Gratiot County in October 1918

The topic of bad health or health threats was not something new to Gratiot County in 1918. Two well-known men were arrested in Alma in July 1918 for “expectorating” (spitting) on the sidewalks. Both men thought the ordinance to be absurd and loudly complained to Justice D.L. Johnson about the enforcement of the law and their small fine.

The late summer of 1918 also would be noted for a crackdown on “social disease” in Alma as the state began to enforce the detention of women who were believed to be carrying social diseases. Some women would be arrested, detained, and then sent to hospitals like the one in Bay City because they were suspected prostitutes who were visiting Alma businesses like the Republic Truck Company. Over at Alma College, plans took place to convert the museum into a barracks for the additional students who joined the SATC (Student Army Training Corps). The college needed more room to house the increased men, and leaders believed that they would turn down SATC applicants after October 1. Because of this, many young men would be crammed into a confined space.

Medicines regularly appeared in newspapers, advising readers about how they could avoid or treat “The Grippe.” “Doctor King’s New Discovery” helped avoid the Grippe and could be found at the local druggist. Or, one could try Scott’s Emulsion, a preventative for the flu “so skillfully prepared that it enriches the bloodstreams, creates reserve strength, and fortifies the lungs and throat.”

As October started, many helped America in the World War by buying bonds, attending patriotic meetings, or by helping the Red Cross. Few people seemed concerned about the impending health crisis that started to descend upon Gratiot County.

Military Deaths are the First Warnings

The first news that Gratiot County residents heard about the influenza epidemic dealt with the deaths of young men at military cantonments. Robert Wachalac, the first one mentioned in the newspapers, died from influenza on September 26 at the Great Lakes Training Station. His father had once owned a foundry in both Alma and St. Louis. Two days later, on September 28, Clair Schlappi from Riverdale also died at Great Lakes. The biggest name that received the most attention in Alma came with the announcement concerning Ammi Lancashire’s death in Philadelphia. Lancashire was the grandson of Alma’s leading founder and benefactor, Ammi Wright.

Soon, the names of county men who died at Camp Custer and their funerals would be announced. Floyd Allen’s name, who enlisted from St. Louis, emerged. Homer Hunt of Elwell would follow. The funerals for the men could be problematic during the epidemic. Glenn Heibeck’s funeral took place at the Ithaca Presbyterian Church, and some people attended. However, Michael Mikilica’s funeral in Bannister took place outside in front of the church. Afterward, he was buried in Ford Cemetery. Earl St. John, who died in Camp Custer, was sent to Breckenridge for a funeral. Dwight Von Thurn of Alma died in a Georgia camp. He contracted influenza while serving as a nurse to other soldiers after volunteering to help the sick.

Once Camp Custer notified families that their son or husband was sick, parents, wives, relatives, and friends took off for camps to see their loved one before he died. The trips took place regardless of the threat of anyone becoming infected. Homer Hunt’s parents also traveled to Camp Custer before he died. Samuel Wheeler of Emerson (Beebe) ran to Camp Custer to see his sick brother. In other trips, W.E.Swope of Breckenridge and Mrs. Thomas Crawford attended their relative’s death in Jackson, Michigan. The soldier died at Camp Croft and had been sent home for the funeral.

Ralston Fleming, an Alma boy who joined the SATC in Ann Arbor, died at the University of Michigan hospital one week after joining the program. Other sad news came when Alma College student and star football player, Ed Foote, died in a Southern camp.

Other news about soldiers who tried to avoid the virus also arrived in the county. Orlo Roberts from Ithaca joined the Merchant Marines and sent word home that he had been sent with other men out into Boston Harbor due to the flu. Captain S.R. Watson wrote that he survived an attack at Camp Dodge, Iowa.

By mid-October, a rumor existed that court-martials – and even executions – would take place at Camp Custer involving doctors who allowed sick soldiers to travel to their homes. It turned out that some officers had been allowed to go to their homes in downtown Battle Creek during the outbreak. However, several soldiers were seen loitering downtown, and the news made its way back to camp and the newspapers. While investigations into the incidents were planned once the influenza crisis abated, the rumors of executions at Camp Custer were called “pure bunk” by the Army. On a side note, if anyone wanted to help a sick man at Camp Custer, they could send cigarettes for them while they stayed in quarantine.

At the end of October, Gratiot County newspapers ran a “Roll of Honor” of twelve men who died so far in service to the county. None of the names included influenza victims, at least not yet.

Conflicting Messages

The arrival of influenza at Camp Custer caused a delay for the departure of any Gratiot County men for their camps that October. On October 3, the county draft board announced that it canceled all scheduled departures for drafted men to cantonments for at least one month.

Slowly, people in Gratiot County started to close public places; however, only for “precautionary measures.” The first indication that people were nervous came when the Alma Suffrage Meeting was canceled; then, the Presbyterian Synod also canceled its meeting in town. By October 17, Alma had officially moved to quarantine. Health Officer Dr. Thomas Carney ordered the closing of all churches, movie theaters, pool halls, and music halls in town. For the moment, Alma Schools remained open as it was noted that “only a few cases of Spanish Influenza” existed in the city. Alma College went to full quarantine just a day before this order. A week later, St. Louis also went and closed public places on October 24.

One incident demonstrates the conflicts of enforcing quarantine with one Alma family, the Wordens, and two local doctors, Dr. Carney and Dr. Thornburgh. When Alma reached thirteen cases of influenza as of October 23, Dr. Carney declared that homes had to post notices that each household was infected. One of these on Woodworth Avenue belonged to the Worden family, where at least two people were sick (one was an infant). Dr. Carney visited the family and declared that it needed to be quarantined, and a sign was put up outside. When the older son, Albert, grew worse, the family changed doctors and called in Dr. Thornburgh, who pronounced that the family suffered from typhoid, not influenza. Thornburgh advised the family to take down the quarantine sign, and Ollie Worden, the eldest son, did so. Ollie had a reputation as a troublemaker and the town drunk, and when he took down the sign and put up another one that read “No Influenza,” people went into an uproar. Many saw Ollie Worden’s actions as just another of his irresponsible acts and someone quickly reported this to Dr. Carney and the health department. The issue in Alma now involved who had the power to declare and enforce quarantines. Because Carney had the backing of the State Board of Health, the Wordens were again quarantined. Another sign was put up out in front of their house. They were also informed that no more resistance would be tolerated. The Worden incident demonstrated that quarantines were to be taken seriously and that there would be consequences for those who did not obey. The case also caused Dr. Thornburgh and another doctor in Mt. Pleasant to be charged, brought to trial in Ithaca, and fined for encouraging disobedience of the quarantine. Sadly, the Worden child during the influenza epidemic.

What should Gratiot County do?

Both Gratiot County, the state of Michigan, and the Federal Government all tried to quickly educate the public about the dangers of the influenza epidemic. Professor MacCurdy from Alma College was the first to do this when he asked the Alma Record to print a list of thirteen things people should know about this influenza virus. Surgeon General Rupert Blue issued this notice to each state as an attempt to “provide all available knowledge” about the influenza virus. The culprit now had a name: Pfeiffer’s bacillus. It moved through body secretions, incubated between one to four days (usually two), attacked the respiratory tract, and vaccines for victims offered only partial success for treatment. While the government acknowledged that quarantining was termed difficult and impractical in some cases, people were told to avoid crowded rooms, streetcars and to look out for those exhibiting coughing and spitting. People also had to stay in warm, ventilated rooms to avoid broncho-pneumonia, which usually followed this influenza.

Another example that the epidemic was spreading through Alma involved the creation and use of masks. Professors and anyone else who left Alma College and came “down the hill” into town were told that they had to wear a mask as the college aimed at protecting those who were in the Student Army Training Corps (SATC). Even the Gratiot County Draft Board members soon wore masks upon orders from the Adjutant General in Lansing.

Red Cross workers also received orders to close and quarantine and would “open as soon as health conditions are improved.” When the Red Cross room reopened just before Halloween, workers had to “exercise reasonable precautions.” Upon entering the room, workers had to adjust their face mask, and then wear it for only two hours at a time. After this time, they had to leave the room and boil their masks for at least twenty minutes before wearing them again. The Alma Red Cross also published a notice for the public about how to make their own masks. A mask needed to be made out of more than three grades of gauze, but butter cloth worked best. A yard and a half of tape was needed for each mask, and the mask should measure at least five by nine inches. A good mask would supposedly protect a person if they stayed at least four feet away from others. However, one needed to stay at least ten feet away from anyone who coughed.

Clerks in all of Alma’s downtown department stores also used them when dealing with customers as precautions. Another example of social distancing existed in the county. The Ithaca postmaster put out an announcement earlier in the month that both adults and children had to stand behind the floor line when picking up packages at the post office.

Surprisingly, another topic of quarantine took so long to take effect in the public schools. Early in the month, the St. Louis schools closed for a short time due to the fear of infantile paralysis. It is not clear how long they stayed closed, but it appears that they reopened. Even after closing different places in Alma by mid-October, the schools remained open there because “only a few cases of Spanish Influenza” could be found in Alma. Alma High School did seem concerned enough to cancel the Alma – Midland football game, possibly because Midland experienced the epidemic as well.

Out in the countryside, it was a different matter. The Beebe school closed first and announced it would remain that way for two weeks, then came the closing of the Sumner school. A string of closings followed in succession: Sethton, Perrinton, North Shade, Washington Township, Rathbone, all closed their doors. A pattern was emerging in Gratiot County: while towns like Alma and Ithaca seemed to avoid the epidemic, it was the Gratiot County countryside that was ablaze with cases of the influenza virus. Things would continue to worsen in rural Gratiot County.

On October 24, as a precautionary measure, Ithaca closed its school even though there supposedly was not an epidemic. As other public places in Ithaca closed, someone commented still that “We are not suffering seriously from the plague anywhere neither do we want to do so. An ounce of prevention.” However, in what would be one of the hardest-hit areas in the county, just before Halloween Breckenridge closed its schools indefinitely.

Churches also closed and could no longer hold services. The church bell at the Ithaca Presbyterian Church still rang each Sunday morning at 10:00 am, reminding people of the Sabbath. The pastor eventually asked each family to make a time of prayer and worship at home by reading the Bible and singing a hymn. Someone from the church still delivered Sunday School papers to homes. The pastor also asked each family to lay aside weekly offerings and send them to the church treasurer.

The Sick

Notices of the sick who suffered influenza started as a trickle in October. “The Sick List,” which each community kept track of, contained a listing of people who experienced different maladies, and it served as communication to warn others. One of the first to become sick, A.S. McIntyre of St. Louis, was at home with three days due to “Lagrippe” early that month. By October 10, the virus hit the countryside, and entire families became sick. The Peter Salisbury Family in New Haven Township were all ill, and ten more people in Middleton became ill at the same time. The Hull Family was having “a serious time with influenza” and fortunately had a nurse to tend to them. The Hulls were fortunate as many families could not find anyone to serve as a nurse. Christian Eyer of Alma headed for Lansing to take care of his daughter because Eyer’s son-in-law was hospitalized with influenza, and “There is not a nurse to be had there.” Finding someone – anyone – to help with a sick household was a real problem for many Gratiot County families.

Within a week, another eight people in Middleton went down, and the churches suspended services. Ten more people in Middleton became sick by Halloween. Four people over at nearby Perrinton soon reported in as sick, followed by another household of five. As things worsened, Dr. Hall and at least three other doctors made frequent house calls. A total of fourteen people would initially become sick in Ashley, and by the end of the month, the total there reached the incredible number of seventy-five with influenza.

Caring for the sick had its challenges. Several teachers returned home to Gratiot County to their families because their school in Flint or Marion closed down, allowing families to see each other. However, for those who traveled to take care of their sick family meant becoming trapped in a quarantine, or worse. Miss Della Struthers, an Ithaca teacher, went home to Pontiac to attend a funeral for a close family friend. At the funeral, her brother became sick, and Della had to stay in quarantine. The same situation happened to music teacher Merrie Jewell who went to help her family in Fowlerville. Jewell was quickly placed in quarantine. Samuel Wheeler ran to Camp Custer to see his sick brother, even as relatives of many soldiers there became ill. Mrs. Roscoe Praether of Breckenridge traveled to Alabama to see her husband in a cantonment, apparently unafraid of the epidemic. When Roland Campbell of Breckenridge made the trip to Pompeii for surgery at Dr. Hall’s hospital, his wife came with him. Unfortunately, Campbell’s wife contracted influenza while awaiting his recovery in Pompeii.

The Dead

Among the first to die early in October included Reverend F.E. Gainder of the St. Louis Baptist Church. In Ithaca, Warren Gross, age 56, died as a result of pneumonia, but his funeral took place at the Ithaca Presbyterian Church. Frank Gunn, the first in Ashley to die, had a private funeral in the undertaker’s room. Only a prayer was said for him then he was quickly buried in the North Star Cemetery. Ashley residents experienced shocked by what influenza did to three members of the Beck family, who all died in Ashley. Little Mildred Beck, age five, died along with her relative, Dorothy Beck. When Mildred died on a Saturday night, her father, Sam, came from Durand to help his sick daughter. The father quickly contracted influenza and died the following Monday morning. When infant Orbie Darling died on a Sunday in Breckenridge, his parents were so ill that they could barely attend a private funeral. A funeral in Bannister took place on October 15 for Private Peter Mikilica, who died in Camp Custer, but the service took place outdoors in front of the church. While all deaths would be tragic, sometimes the loss of one person hit a village or town, especially hard. In Perrinton, Howard Phelps typified the fate of one of the younger adults who died. Phelps served as village clerk and telegraph operator, and he was well-liked and respected in the community. When he suddenly died at age 26 and in the prime of life, people could not believe that such a young adult could perish.

How the Public reacted to the Influenza Epidemic in October 1918

On October 3, approximately 2,000 people still attended a Liberty Loan meeting in St. Louis in front of the Commercial Bank. Just as the virus hit, Middleton people met for prayer meetings at the Methodist Church. The Strubles showed some foresight in Ithaca by volunteering to close the Ideal Theatre before being ordered to do so. Large numbers of people from Breckenridge drove to Alma to see the war trophy train that pulled in with several flat trailers filled with guns, German airplanes, and tanks. The showing was held to raise Liberty Bonds. State Representative Fordney, who represented Gratiot County and who had just planned a tour of the county for a series of speeches, canceled all of them. Instead, he planned to “drive about some” in Gratiot County to talk to a few people. The St. Louis Methodist Church thought enough of the threatening situation to postpone the dedication of its church until December.

And in Alma, toward the end of the month, the newspaper started printing first page notices of those who died. On October 31, the headline of an article that said: “‘Flu’ Situation is not Alarming.” The Alma Record justified the headline by writing that only two or three severe cases had been reported in the last day. Also, the paper mentioned that Alma College was the only college in Michigan with students in the SATC that had escaped the flu. True, people in the Gratiot countryside were suffering, but Alma “hoped to escape the toll” being taken in places like St. Louis, Ashley, Perrinton, and Middleton. Maybe Gratiot County could soon return to normal.

It would not be so.

Copyright 2020 James M Goodspeed

Those who became sick during October 1918 included:

A.S. McIntyre, St. Louis

Mrs. J.G. Kress, Ithaca

Peter Salisbury Family, New Haven

Mrs. B. Hudson, Newark

Ten people in Middleton (October 10)

Eight people sick in Middleton (October 17)

Mrs. Harvey Humphrey, New Haven

Two people sick in Ashley (October 17)

Fisher and Shaw families – Wolford District

Five people in Hamilton Township (October 17)

Fourteen people in Ashley, including the George Gallup family (October 24)

Jack Burch in Rathbone

Alf Crawford in Breckenridge

Seven sick in Middleton (October 24)

Mable Pendell – Middleton

Nellie Peters – Pompeii

Charles Dodge – Pompeii

Mrs. John Martin – North Shade

Hull Family – Middleton

Otto Fenner & wife – St. Louis

Glenallen Caldwell – Ithaca

Mrs. Rolland Campbell – Breckenridge

Baird Family – East Alma

Mrs. John Delling – Ithaca

Mrs. Hooker & 5 children – Perrinton

George Browning & wife – Riverdale

Seventy-Five people – Ashley (October 31)

Lora Seaman – Sumner

C.T. Pankhurst – North Star

Ten sick in Middleton (October 31)

The unknown number (“reported only a score”) in Alma (October 31)

Those Who Died in October due to Influenza who were either from Gratiot County or were tied to the County:

Robert Wachalac – Great Lakes

Clair Schlappi – Riverdale

Ammi Lancashire – Philadelphia

Floyd Allen

Rev. F.E. Gainder – St. Louis

Warren Gross – Ithaca

Floyd Schrider – Carson City

Glen Rickard – Matherton

Homer Hunt – Elwell

Mildred Beck – Ashley

Dorothy Beck – Ashley

Sam Beck –Ashley

Orbie Darling – Breckenridge

Frank Gunn – Ashley

Four people dead in North Shade

Ralston Fleming, Alma boy, died in Ann Arbor

George H. Smith – Alma

Howard Phelps – Perrinton

Mrs. Irvin Pankhurst – Pompeii

William C. Smith three-year-old son – St. Louis

Albert Worden – infant child – Alma

Copyright 2020 James M. Goodspeed