Working class communities have always been subject to systematically hostile policing. But conditions in Brixton as in many other areas in Britain became much worse in the 1970s. Local communities, black mainly but white as well, were often in a state of siege, confronted by repeated raids, with or without warrants, trashing of people’s houses, intimidation, harassment on the street, searches, assaults. Black people were told that if they didn’t want to get nicked they should stay indoors. In fact many parents did forcibly try to keep their teenage (and younger) kids indoors at weekends to stop them going out. Partly this was fear of them getting nicked, though many older more law-abiding Caribbean folk did feel they were losing control of their more rebellious and militant kids. The massive widespread use of Section 24 of the 1824 Vagrancy Act to arrest people on suspicion that a crime may have been about to be committed, led to its infamous nickname – the ‘SUS’ law. The charge was “loitering with intent to commit a crime”_ – cops only had to state that the suspect had done something to arouse their suspicion and then something else that led them to think a crime was about to be committed (usually theft), to justify an arrest. No evidence, independent witnesses, anything, was needed get a conviction.

SUS was heavily aimed at young black people; for instance 89% of sus defendants attending Balham Juvenile Court in 1976 were black. Lambeth was consistently the highest area in London for sus arrests.

Among the places where black kids could get off the street away from police harassment, were local black youth clubs; but as a result, raids and searches of the clubs gradually were a regular occurrence. Police would storm in: “Twenty to thirty police burst into the premises, they knew every door, toilet etc… They burst in like commandos in Africa. They grabbed people by their hair and necks… they said they were looking for somebody… They took away almost everybody out of the club…”_ Raids caused increasing anger: another incursion “caused chaos in the club. Some members became very restive and excitable; others were aggressive as they were not allowed to leave the building… The end result was one of noise and anger against the police.”_ In at least one case they brought a bloke in who they claimed was a mugging victim, to look for the alleged perps, only it later turned out this guy was another copper, posing as a ‘victim’.

Brixton, with its large west indian population and a strong street culture that police saw as threatening, was a major target for police operations, which often turned into sieges of the area, mass arrests and beatings.

To this day, but even more so in the ’70s and ’80s, in Brixton, any small incident could escalate, often because any call for assistance by an officer (often over the most minor ‘offence’) would be answered with massive force. Cops over-reacted routinely. The open police radio allowed coppers not actively engaged with anything else to race to any incident.

In response, younger black activists, increasingly influenced by the powerful Black Power movements in the USA, began to organise resistance to police violence. Visits from US leaders like Malcolm X and Stokely Carmichael (who spoke at a rally in Brixton in 1967), and later the activities of the US Black Panther party, inspired a number of UK-based groups. But they were also forged by their own daily experience on inner-city streets. Many of the activists who formed the early radical black groups shared a similar background – predominantly arriving in Britain as young children or early teenagers (often between 1959 and 1963), children of the first generation of migrants. The culture shock of arrival here, the experience of racism, both casual and institutional and low quality of life, the lack of opportunities, was blended with the realisation that they were likely here for good, and would have to fight to establish their position. This militancy began to distinguish them from the majority of their parents. Attempts to turn existing race relations groups into black militant groups, led to splits and divisions in organisations like the Institute of Race relations, the Campaign Against Race Discrimination and others.

The Universal Coloured People’s Association, Britain’s first Black Power group, founded in 1967, had a branch in Brixton, holding Black Power rallies there. It only lasted a few short years, but from it emerged the UK Black Panthers in 1968. Another group that fed into the British Black Panthers, in its embryonic phase after the Mangrove 9 trial was called the Black Eagles, which met I think in West London. Later the Black Unity and Freedom Party also emerged from the UCPA.)

The UK Black Panther Movement was strongly influenced by its US counterpart. Based at the Black People’s Information Centre, 38 Shakespeare Road, Brixton, at their height they had 300, mainly working class, members in London, They produced a paper which they distributed door to door and in Brixton market, held public meetings, agitated, demonstrated, publicly opposing police violence and supporting people attacked, and framed by the cops. From this their activity spread into housing, education, supporting anti-colonial movements, producing revolutionary literature.

Black power groups mobilised hundreds and later of mainly younger black people up and down the UK; through “demonstrations, boycotts, sit-ins, pickets, study circles, supplementary schools, day conferences, campaign and support groups”, aimed at racist immigration laws, police harassment, discrimination in housing, employment and education, many more were to be drawn in as the 70s went on.

The Panthers set up education classes for local kids, running Saturday schools and Black Studies groups, and had a library as well as organising anti-racist demos, producing both propaganda and informational material about black struggles around the world. They also ran social and cultural events: Black power activities also had a strong cultural element – dances, with sounds systems, poetry groups…

But the war by the police on the local black community remained at the heart of their practice.

The celebrated Mangrove case in Notting Hill, (where a march against police harassment had led to nine leading activists – including Darcus Howe – being charged with incitement, but who had defended themselves in court and been acquitted) had been a coalescing force in the development of black militant politics in London. It brought together small groups and individuals and began the process of turning them into a movement. At every stage of the case, both in the legal arena and on the streets, black self-organisation had pushed to a new collective level; both defendants like Darcus Howe and supporters/participants in the campaign were drawn into groups like the Panthers.

The groups opposed everyday police racism and violence. And of course in the nature of such things, Brixton Police responded, by harassing the Panthers at every turn. British Black Panthers warned in October 1970, of a deliberate campaign ‘pick off Black militants and to intimidate, harass and imprison black people prepared to go out on the streets and demonstrate’.

Panthers and other black activists were followed and stopped, in the street, while selling their papers; their fundraisers and the Brixton HQ were repeatedly raided. The usual catalogue of bizarre arrests and colourful charges visited by the peelers on rebels and protesters mounted up.

In March 1970 (in fact 48 years ago tomorrow, the 16th) four members of the Fasimbas, a Lewisham-based radical black organisation, were pounced on the then notorious Transport police led by the notorious Sgt. Ridgewell, at the Oval tube station, and charged, with trying to ‘shop’ (mug) two old people and attempting to steal a policewoman’s handbag, also assault on police (as usual). All actively involved in the Fasimbas’ supplementary school, they were carrying books with them for the school project when they were arrested. Beaten up inside the police station, forced to sign confessions, the ‘Oval 4’ were sentenced, the youngest to Borstal, the three others to two years imprisonment. However they were later all released on appeal.

In August 1971, a Black Panther dance at Oval House, Kennington, turned into to a mini-riot, after cops were refused entry to allegedly follow two ‘suspected young thieves’. More police turned up, carried out a search, but no two youths found. A fight then broke out, several people arrested, and three at least charged. They got suspended sentences.

On the eve of the National Conference on the Rights of Black People in 1971, the Panthers HQ was raided, their files rifled; the group was bogged down in court for months.

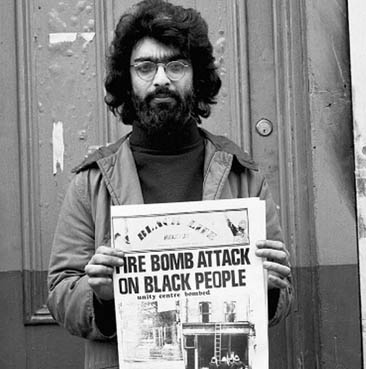

Unity Bookshop

In 1973 the Black Panthers squatted 74 Railton Road, to open it as a black bookshop to sell their increasing black literature, and their paper, Freedom News. Farrukh Dhondy, then a leading Panther member, takes up the story [a warning: it’s a shocking tale of a narrow escape from fire.]

“We used to run a newspaper called Freedom News and we had a lot of books for sale which we used to sell outside Brixton from another handcart, and Ridley Market in Dalston. So we had all these sorts of bookshop and we thought we should have a proper bookshop and so we squatted a place called 74 Railton Road on what was then playfully known as the frontline because people used to hang about there all the time and other activities. So we had this Freedom News bookshop on the ground floor, and it was a derelict building, but a friend of mine called Keith, Keith Carling, he was an architect, he’d just finished architecture school, so he knew how to build and plaster and stuff. So, he put in toilets and showers and we made it decent. So we had two flats and we had a basement room in which a fellow who I can only remember as Afrika, because he called himself Afrika with a K, and he moved in there and he played the bongo drums most of the night and disturbed everybody, but the bookshop ground floor, me first floor… Keith first floor, me second floor, and on the 15th of March 1973, the date is printed in my head, I was asleep about four in the morning and suddenly I woke up choking, I didn’t have a bed, I had a mattress on the floor, or a couple of mattresses on the floor, and I woke up choking wondering whether I’d left the fire on or what, what was choking me. I couldn’t see because the smoke was so thick, so I got up and stumbled towards the fire, but of course the fire was off, and then I saw the smoke coming through the shut door of the first floor. I opened that door door and the fire was raging on the staircase and I couldn’t get the door shut because of the draught, it was… it banged then and I went to the window, all this time not breathing now, so a minute/two minutes without breathing, you know what it’s like when you duck under water, and I opened the window and took one deep breath of fresh air or whatever there was. Nobody about and the glass of the front, the glass front of the bookshop was breaking outwards with booming noises, you know, which fire does, I believe, it heats up the glass, and blasts it outward, and I heard all these blasts and then I heard the neighbours shouting, ‘Oh god. Oh god’, you know all this, and I just shouted, you know, ‘Don’t call god, call the fire engine, yes?’ I was only in my underwear, so I didn’t know what to do, whether to grab my clothes, go back into the smoke-filled room, I was just gasping for air. I jumped from the thing, I had to get out because the fire was coming up, so I jumped and I landed in the burning glass, you know, red hot glass and cut my feet and broke my ankles and that, but I struggled up and by that time some neighbours had gone and called the people at Shakespeare Road, which was one of our bases, and Ira [ ]and I think Neil [Kenlock], people came out, they came rushing out to see if I was okay. A neighbour opposite, just a guy I didn’t know even, he got a coat and he put a coat around me and sat me down on the steps and I waited until the fire engines and police and so on came. The fire chief definitely came to me and said, ‘You’ve been set on fire, there’s a petrol bomb.’ Yes a chap threw a molotov cocktail in through the glass. I didn’t hear a crash. So, I hung about, they phones friends for me and a couple of mates came. They said ‘What do you want to do?’ I said, ‘I just want to go to school’, right, where I was teaching, even though I had broken ankles. They took me to the thing and they bandaged it up, there was nothing they could do, that was it, so I sat on the steps until school opened, this was kind of 6.30, 7.00, and I sat there until the headmaster and people turned up and said, ‘Why are you in a coat and underwear?’ ‘Because I’ve got nothing else [laughs], this is a borrowed coat, the underwear is mine,’ and so that it was it. The newspapers said that evening, the morning papers didn’t have it, the Evening Standard, or whatever it was then, the Evening News, had five places had been bombed that night, and this bookshop was one of them, some Asian shops and some black project somewhere and all in the same day… the police never did anything. One neighbour said that it was a motorcyclist who chucked the bomb and moved on, so nothing ever happened, no prosecutions took place and the place was a shell, it was burnt out, that was the story…”

Police apathy towards the attack was hardly surprising – the frontline was widely despised by the cops, enemy territory they policed only in numbers and violently. The Panthers were vocal opponents of the cops; and police racism was notorious. In the 1970s, sympathy towards the rightwing nationalist National Front (the NF, many of whose core members were long-time Nazi sympathisers, though they had gathered increasing support among the wider white population), agreement with its views, if not actual membership, was widespread among the police, and this was true of Lambeth. Black people coming up against the police, facing or reporting racist attacks, or crime against them in general, would usually be faced with racist comments and treatment, if the cops bothered to turn up at all.

And bizarrely, even in Brixton, the then growing National Front did attempt to show its ugly face publicly. Several times in the decade, and at least twice in 1978, the police protected the National Front in Brixton. In April at Southborough Park Junior School, 1500 police protected an NF electoral meeting, while 800 anti-fascists demonstrated nearby. Police co-operated with NF stewards, and closed off access to parts of nearby estates and harassed people who were trying to get to their homes, as well as nicking 6 black youths leaving the demo (under sues). In May cops protected Front members selling their racist shite along the Frontline in Rail ton Road – where they might otherwise have had difficulty leaving in one piece. A tiny number of Nazis were escorted by large numbers of police. Coming so soon after the NF march in Lewis ham in 1977 – which had seen a massive police operation protecting a Front march from thousands of anti-fascists, locals and leftists of all stripes, ending in huge battles throughout southeast London – it seemed obvious that the police were hand in glove with the Front. Contrast this with police treatment of black or anti-racist demos – many of which were systematically attacked by the cops in the late ’70s and ’80s.

The arson attack on the Unity Bookshop, presumably by fascists of one stripe or another, was not a unique event. Racist fire-bombings in the 1970s were not even uncommon, often against Black and Asian people in their own homes, but also against black and anti-racist spaces, cultural venues or leftwing centres. Other high-profile targets of arson that was suspected to be fash-inspired at the very least, included the Albany Centre in Deptford, the nearby Moonshot youth Club in New Cross, the Commission for Racial Equality HQ, the SWP’s offices… to name but a few.

The most high profile fire believed to be the result of racist arson was the New Cross Fire in 1981, where 13 black teenagers died (another died of injuries later), which was ignored and played down by police, who did nothing to investigate. This horrific event sparked the Black People’s Day of Action in March 1981, a huge angry march through London… And the climate of racist policing and blatant refusal to do anything about these kind of attacks contributed to the rage and hatred of the cops that gave birth to the 1981 riots…

But rightwing arson attacks didn’t end in the 70s or 80s… in our own time attempts were made to twice burn the 121 anarchist centre, just down Railton Road from the Black Panthers’ shop, in the early 1990s… (Their friendly neighbour chased off the crap arsonists in 1993)… and in 2013, the anarchist Freedom bookshop in Whitechapel was badly damaged by arson, again, probably by Nazis. The police stirred themselves again on that one… And its not only political targets: in recent years, tens of mosques have been targeted for arson, as have eastern European homes both before and since the Brexit referendum. Whether its active fascists, common or garden racists, little englanders – rightwingers love nothing so much as burning out foreigners and people who won’t put up with their swivel-eyed bollocks.

Postscript: The terrace that the Unity Bookshop was part of has, I think since been at least partly demolished. Many shopfronts were run down and empty at that time, and were regularly squatted for various projects. A couple of doors down from the short-lived Unity shop, a year later, no 78-80 Railton Rd, (in front of the also squatted St George’s Residences), included a squatted Claimants Union office, a women’s space, and the famous South London Gay Community Centre, around 1974-6.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

For a brief introduction to the UK Black Panthers in Brixton and the racism and police violence they were resisting, read In the Shadow of the SPG

The interview with Farrukh Dhondy (who went from the Panthers, to seminal Black magazine Race Today, to writing and Channel Four), was lifted from the excellent ‘The British Black Panthers and Black Power Movement’, interviews with and photos of the UK Panthers, published by Organised Youth.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

An entry in the

2018 London Rebel History Calendar

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

See also:

past tense’s series of articles on Brixton; before, during and after the riots of 1981.

Part 1: Changing, Always Changing: Brixton’s Early Days

2: In the Shadow of the SPG: Racism, Policing and Resistance in 1970s Brixton

3: The Brixton Black Women’s Group

4: Brixton’s first Squatters 1969

5: Squatting in Brixton: The Brixton Plan and the 1970s

6. Squatted streets in Brixton: Villa Road

7: Squatting in Brixton: The South London Gay Centre

8: We Want to Riot, Not to Work: The April 1981 Uprising

9: After the April Uprising: From Offence to Defence to…

10: More Brixton Riots, July 1981

11: You Can’t Fool the Youths: Paul Gilroy’s on the causes of the ’81 riots

12: The Impossible Class: An anarchist analysis of the causes of the riots

13: Impossible Classlessness: A response to ‘The Impossible Class’

14: Frontline: Evictions and resistance in Brixton, 1982

15: Squatting in Brixton: the eviction of Effra Parade

16: Brixton Through a Riot Shield: the 1985 Brixton Riot

17: Local Poll tax rioting in Brixton, March 1990

18: The October 1990 Poll Tax ‘riot’ outside Brixton Prison

19: The 121 Centre: A squatted centre 1973-1999

20: This is the Real Brixton Challenge: Brixton 1980s-present

21: Reclaim the Streets: Brixton Street Party 1998

22: A Nazi Nail Bomb in Brixton, 1999

23: Brixton police still killing people: The death of Ricky Bishop

24: Brixton, Riots, Memory and Distance 2006/2021

25: Gentrification in Brixton 2015

Leave a comment