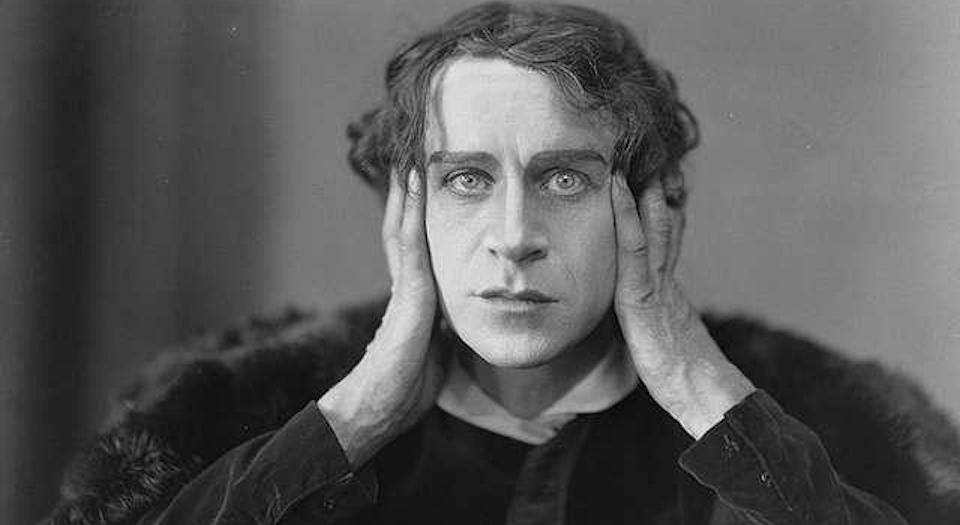

Hamlet is talking to himself again.

“Oh that this too too solid Flesh, would melt,

Thaw, and resolue it selfe into a Dew:

Or that the Euerlasting had not fixt

His Cannon ‘gainst Selfe-slaughter. O God, O God!

How weary, stale, flat, and vnprofitable

Seemes to me all the vses of this world?”

(from the First Folio, 1623—if you would like to read this play in this early edition: https://internetshakespeare.uvic.ca/Library/Texts/Ham/ )

(And welcome, as ever, dear readers.)

Hamlet often does so, his seven soliloquies being among the most famous of all of Shakespeare’s speeches, (for a really interesting essay about these, see: https://www.shakespeareflix.net/2014/10/accurate-list-of-hamlets-soliloquies.html )

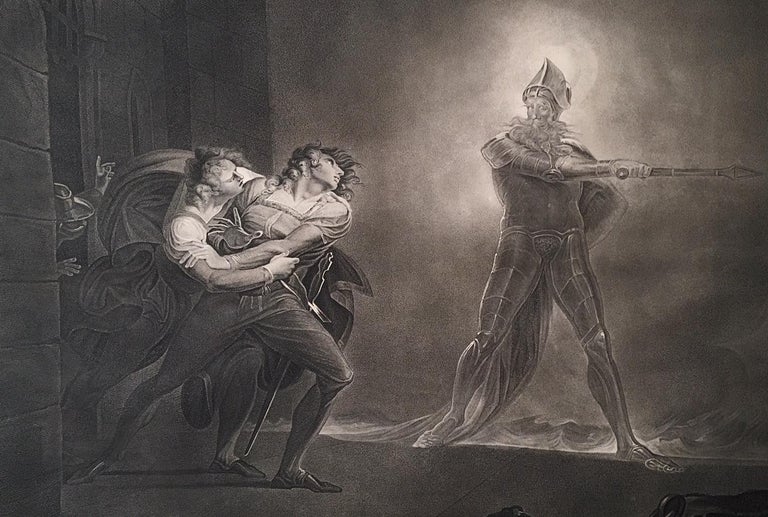

but Hamlet does have a friend from school who has come to attend his father’s funeral, Horatio, and it’s at Horatio’s urging that Hamlet first sees the ghost of his murdered father.

It’s also to Horatio that Hamlet talks about Yorick the jester

and meditates on life and death.

And, when he’s dying, it’s to Horatio that Hamlet entrusts his story, saying, basically, “clear my name”.

Although he talks a good deal to himself, we have a much fuller sense of Hamlet because of his dealings with Horatio.

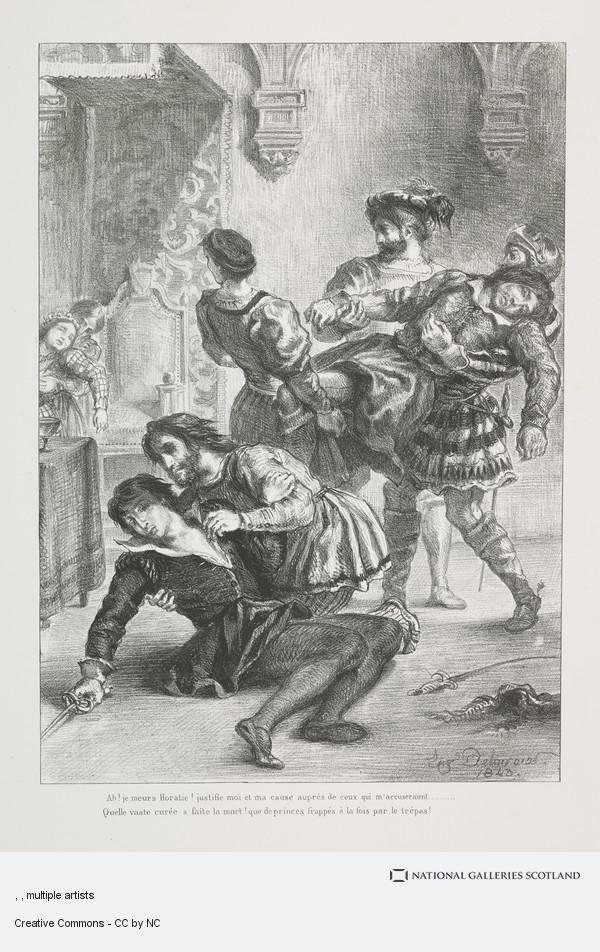

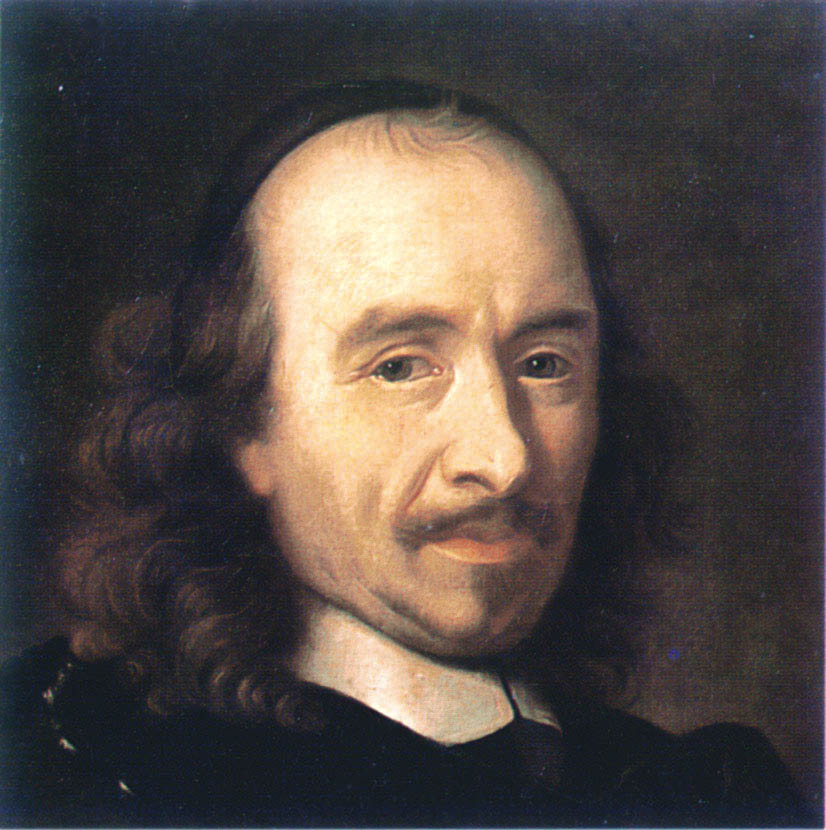

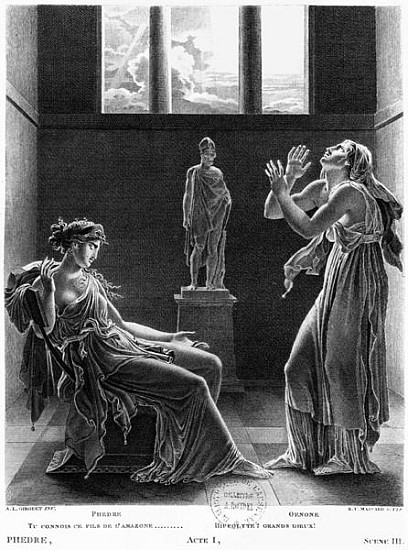

The older literary term for this kind of character is confidant/confidante, the spelling of which suggests English gets the word from French, as the Latin original is confidens, ”trusting in (someone/something)”. This was the term for a standard character in French tragedies of the 17th century by authors like Pierre Corneille (1606-1684),

and Jean Racine (1639-1699),

where many major characters have a secondary figure who acts like Horatio—as Oenone the nurse does for Phedre in Racine’s 1677 play.

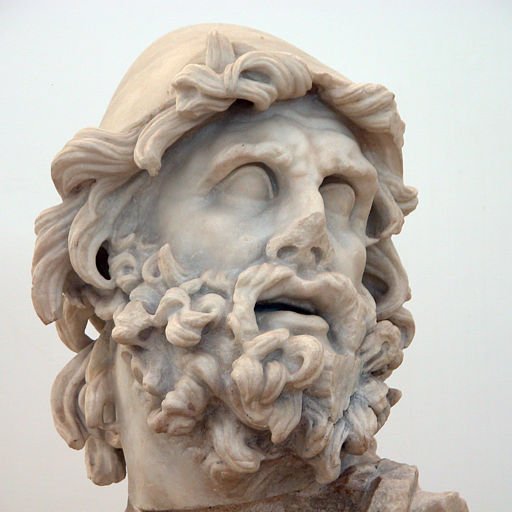

In our world, we might call Horatio Hamlet’s BFF, and the idea of a hero having one goes far back into the history of western literature. Odysseus often seems to be the archetypical loner,

even though, by the end of The Odyssey, his son Telemachus, and several of his serving men help him in dealing with the 100+ suitors and their servants.

Other Greek literary figures, however, are often paired,

Achilles with Patroclus,

Orestes and Pylades,

even Heracles, with his nephew, Iolaus.

In Vergil’s Aeneid, Aeneas has a shadow in Achates

who is even given a repeated adjective which reflects his closeness to his friend, fidus, “faithful”.

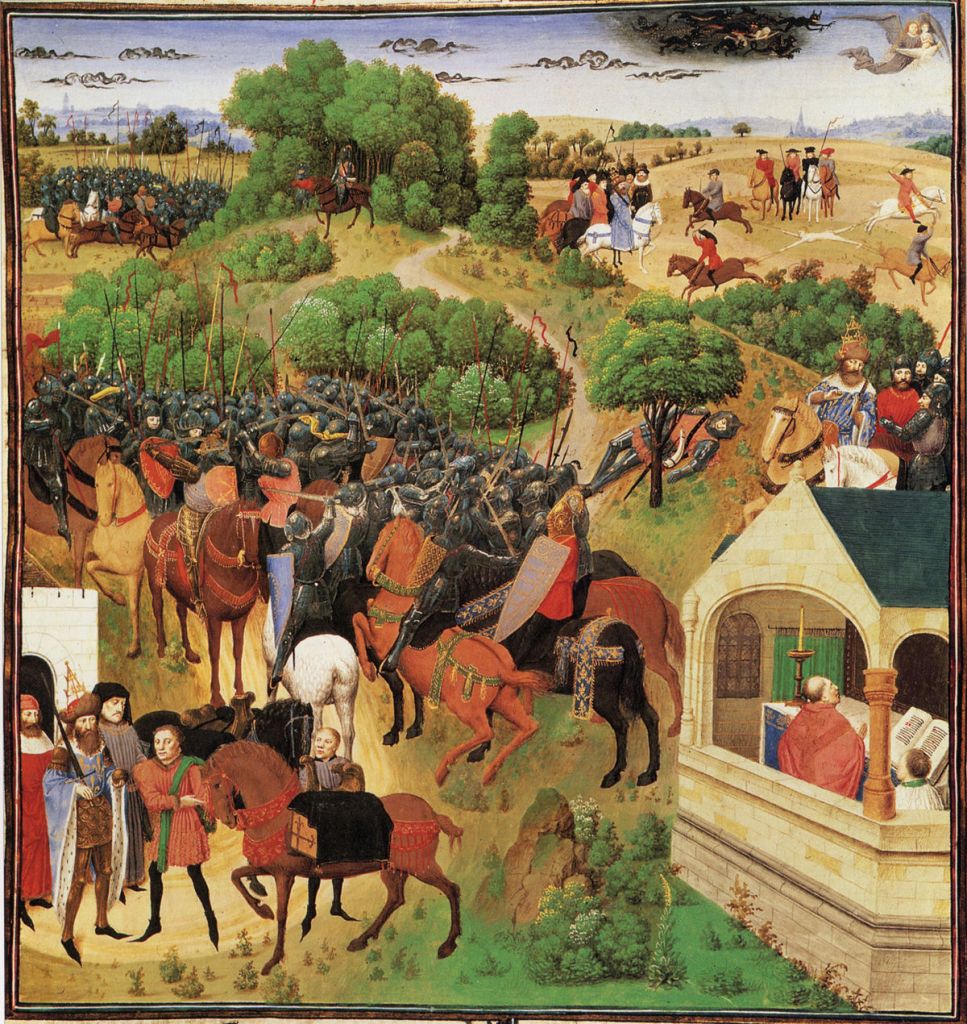

There are more of these through the centuries, everyone from Oliver, Roland’s friend in the 11th-century Chanson de Roland

to Dr. Watson in the Sherlock Holmes stories–

and early mystery stories seem almost to require them, such as the combination of Lord Peter Wimsey and Bunter in the novels and short stories of Dorothy Sayers (1893-1957)

and Albert Campion and Lugg in the novels of Margery Allingham (1904-1966).

Bunter and Lugg are servants, and obviously not of the same social class as their masters, and Lugg is a retired burglar. His stated goal, however, is to make the seemingly-feckless but obviously upper-class Campion respectable and this provides a second form of confidant: the comic side. This parallel of comic with serious is as old as the 5th-century BC dramatist, Aristophanes, whose god, Dionysos, has a slave named Xanthias, in whom he confides in the play, Frogs of 405BC.

Classic comic confidants would include characters like Sancho Panza in Miguel Cervantes’ (1547-1616) Don Quixote

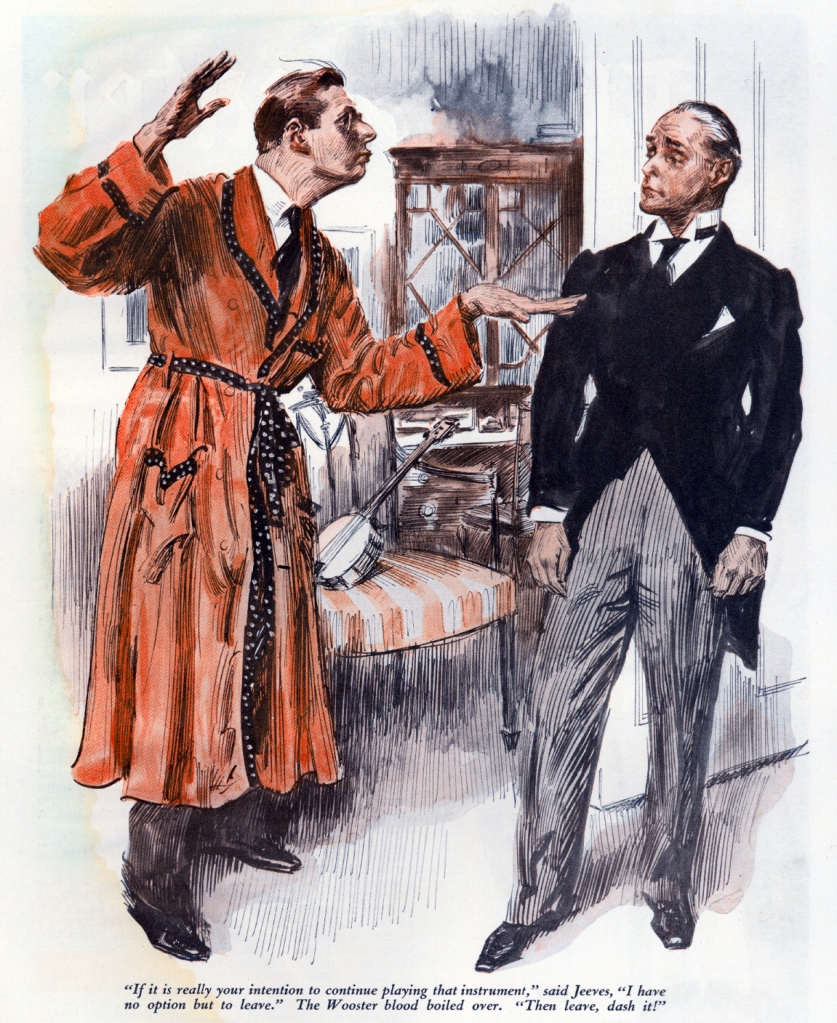

and Jeeves in PG Wodehouse’s (1881-1975) novels and short stories about the cheerful idiot, Bertie Wooster.

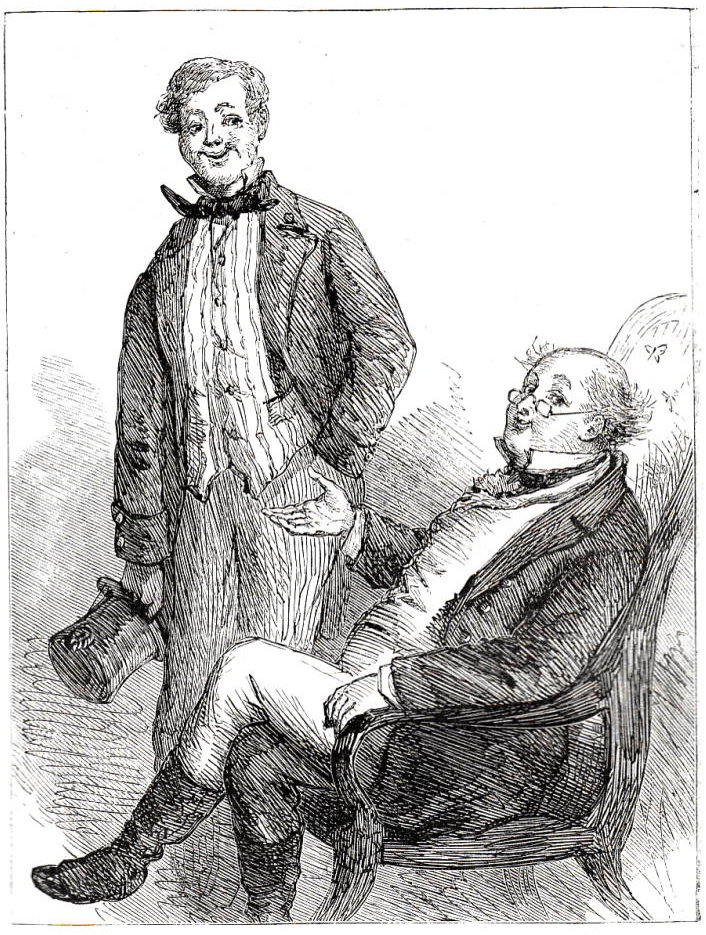

People like Xanthias and Sancho could easily fit into the purely comic category, but Jeeves, in an odd way, is involved in the comedy, but also steers Bertie out of many of his worst disasters, putting him into a slightly different category and two other figures in this category have, I think, a special resonance for the inspiration of this posting, both from novels by Charles Dickens (1812-1870). These are Sam Weller, from The Pickwick Papers (1837)

and Mark Tapley, from Martin Chuzzlewit (first published serially in 1842-44).

Both of these are lower class men by their manner of speech, but clever, resourceful, and like Achates, faithful to their masters, Sam to Mr Pickwick and Mark to Martin Chuzzlewit. And thus it is more than the name of Mr Pickwick’s servant which brought to mind another Sam.

When teaching The Hobbit this fall, I had been struck by the fact that most of what we know about Bilbo comes from the narrator or from Bilbo’s internal monologue: for all that he’s in the company of a gang of dwarves, he has no real friend among them. He manages to turn from the timid Baggins of the book’s beginning to the bold Took of later chapters almost completely by himself and our knowledge of that development comes to us almost entirely through the narrator. It’s easy to remember the physical side of Sam, how he grits his teeth and goes on, no matter what, even to carrying Frodo up Mount Doom, but

there is another side to their relationship. Frodo and Sam are always talking and that back-and-forth often reveals the thoughtful side of Frodo and how his sense of himself and the world changes over the span of the book. Among other conversations, I think of what may be my favorite between the two, at the end of which Frodo seems to be teasing Sam, who replies:

“ ‘Now, Mr Frodo…you shouldn’t be making fun. I was serious.’

‘So was I,’ said Frodo, ‘and so I am. We’re going on a bit too fast. You and I, Sam, are still stuck in the worst places of the story, and it is all too likely that some will say at this point, “Shut the book now, dad; we don’t want to read any more.” ‘ “

And here is where we learn more about Sam, as well:

“ ‘Maybe,’ said Sam, ‘but I wouldn’t be one to say that. Things done and over and made into part of the great tales are different.’ “ (The Two Towers, Book Four, Chapter 8, “The Stairs of Cirith Ungol”)

which makes me want to go back to Hamlet and see what more I can learn about Horatio.

Thanks as always for reading,

Stay well,

And remember that, as ever, there’s

MTCIDC

O

ps

Today is English poet John Milton’s birthday (1608-1674).

Here’s a LINK to one of his richest descriptive works, “L’Allegro”: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44731/lallegro

and tomorrow is Emily Dickinson’s (1830-1886).

Here’s poem #1286

There is no Frigate like a Book

To take us Lands away

Nor any Coursers like a Page

Of prancing Poetry –

This Traverse may the poorest take

Without oppress of Toll –

How frugal is the Chariot

That bears the Human Soul –

Remember them today and tomorrow.