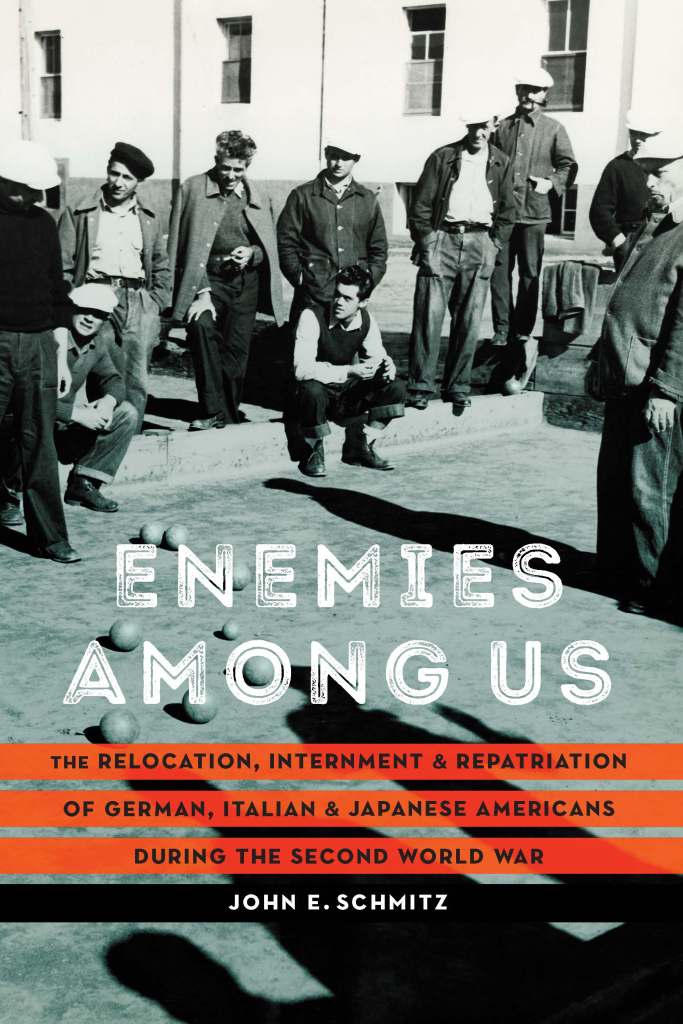

John E. Schmitz is a professor of history at Northern Virginia Community College–Annandale. His book, Enemies Among Us (Nebraska, 2021), is new this month.

William Faulkner is often quoted by historians for saying “history is not was, it is.” For me this idea, this truth, resonates in several profound ways. Growing up in Raleigh, North Carolina, I often told neighborhood kids about my father’s internment during the Second World War, which I learned about by listening to his recollections of Camp Crystal City, Texas. He spent three years there, from age seven to ten, going to school, swimming, playing in the nearby orchards, and having many experiences typical of a child—minus the barbed wired, guard towers, and lack of freedom, which, thankfully, younger children are not able to comprehend fully. My father viewed the camp in a mainly positive light, although that changed over time. I remember my grandfather as being often sullen and bitter—it took me many years to understand why. My grandfather was thirty-five when he along with his wife and three children (a fourth child, Christa, would later be born in the camp’s hospital) were interned, and he understood fully what the experience meant. Not only did he lose three years of freedom, his job, and many of his possessions, but he, and others, were warned by authorities to keep their wartime experience to themselves, lest their lives be made more “difficult.” As I went to high school and then college, I wanted to know more about what happened to my father and his family, and why as my family’s experience, what was, assuredly impacted my life growing up as it still does and is doing so today. The past indeed is prologue.

My long interest in both history and my father’s family led to a master’s thesis, the first work on German American internment, which then led to a dissertation that was the first to compare the experiences of all three major “enemy” groups—German, Italian, and Japanese Americans (aliens and citizens too) as well as thousands more Germans, Italians, and Japanese residing throughout the western hemisphere. I learned so much about the nation and about policies that impacted many hundreds of thousands directly and millions more indirectly. We are a nation of ideas and principles. This is as true today as it was during the world wars and before. Especially during times of stress (whether military, cultural, economic, political, religious, or ideological), I have come to realize the power of fear, I more fully understand that we are a nation of ideas, and when those ideas are attacked, and when officials and the public at large dehumanize others, the costs and consequences can be great. As I write this, the country is again in crisis—we have recently experienced an insurrection, an internal attack that Sinclair Lewis and others have long predicted, and a Confederate flag, a symbol of racism, intolerance, oppression, and gross human indecency, was paraded proudly by white supremacists and other thugs who believed a great lie repeated in the style of Hitler by the former president which then led to action against those newly labeled by the former president and his minions as enemies among us. Over the past few years, we have seen innocent families being ripped apart, children forcibly put in cages, and countless numbers of people being treated as less than human in part because of names and labels, many created and repeated by those with influential voices, including, sadly, the forty-fifth president. Once again, we are bearing witness to the power of words, labels, fears, and lies. My book tells a still neglected tale, but it also reminds us of what can happen when fear leads to calling some among us enemies, or worse. It remains unknown how our nation will continue to act toward those whom it fears and labels as enemies among us. Often we hear that the past is prologue, that history repeats itself unless we learn its lessons—perhaps this is true, but until we start valuing all people equally and learn to temper our own insecurities, we are likely to perpetuate this vicious cycle. It was once said we should love our enemies, for where is the profit in loving only those who love us. Wise words.

What emerged from my investigation of history and family is more than just a story of internee experiences. Indeed, those German, Italian, and Japanese Americans who experienced relocation or internment personified the deeper social and cultural rifts of a democracy under stress. Their stories are those of individual versus national rights, personal versus group identity, and fallacies versus facts. Enemies Among Us will, I hope, serve as cautionary tale reminding us of what can happen when complex social, economic, political, and military circumstances combine to create a fearful atmosphere in which individuals are stereotyped and suspected of wrongdoing solely because of their race or ethnicity. Americans came to see arresting, relocating, interning, and repatriating their fellow aliens and citizens as just. How might we treat our fellow Americans and resident aliens, human beings all, in future times of stress? A suggestion from long ago offers some guidance: “When an alien resides with you in your land, you shall not oppress the alien. The alien who resides with you shall be to you as the citizen among you; you shall love the alien as yourself” (Leviticus 19.33–34). History is and will be.