Mona El Hallak is standing in what was once Photo Mario, a neighbourhood photographer’s studio located on the ground-floor of Beit Beirut in Sodeco. In front of her are 80 negatives displayed in a glass cabinet.

“This one is my favourite,” she says, pointing towards a medium format negative. “See the twirls, the capillary breaks, the yellows, the blues. It’s artistic the way it has deteriorated.”

The 80 are just a fraction of the 8,000 Hallak discovered when she first entered the building in 1994.

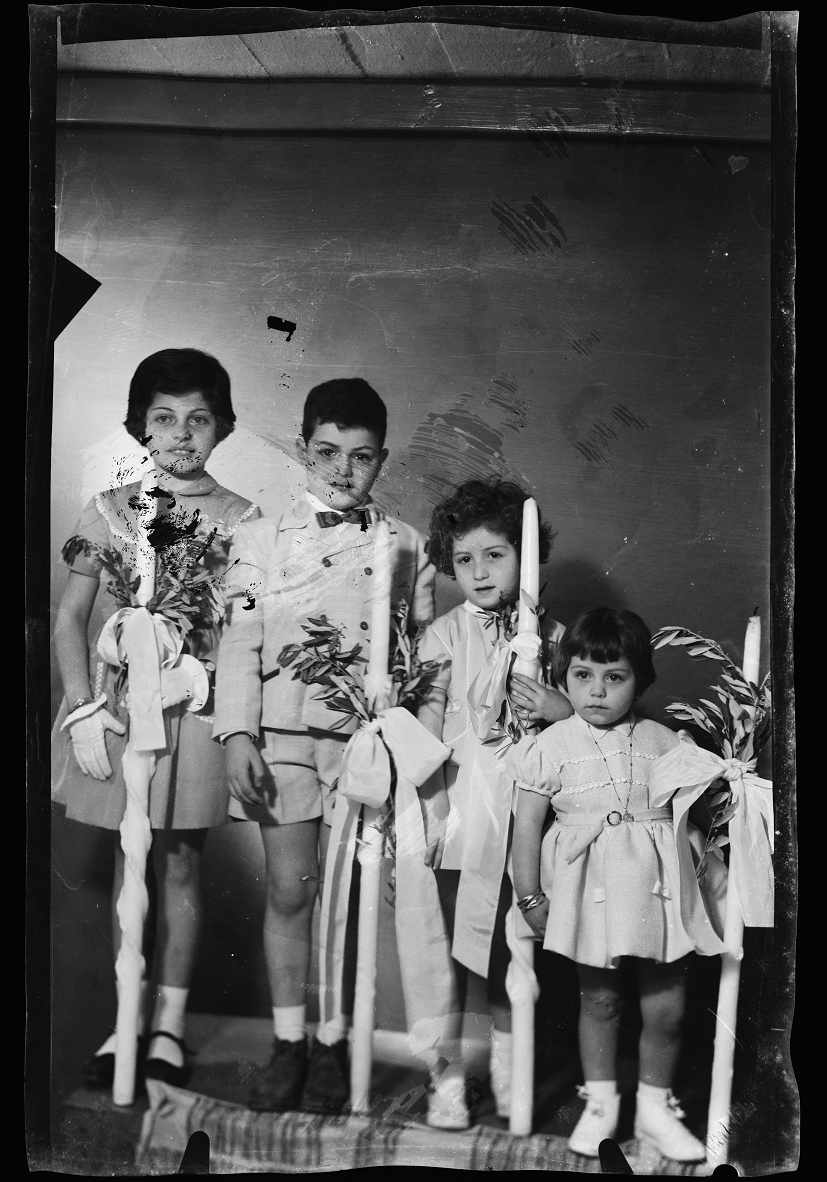

“When I looked at the photographs for the first time they would look back at me,” she recalls. “And because they’re negatives they had these white eyes. There were men and women, girls and boys, families, portraits of couples. They had different styles of dress and posed in different ways. It was life in all its variety.

“I particularly remember a photograph that looked a lot like one my uncle had taken, and I realised that you identify with photographs beyond whether you know the person or not. You identify with a pose or a family portrait similar to one your own family had taken.”

It was this realisation that led to the creation of the Photo Mario Archive Project, an initiative that seeks to recapture memories, not only of the studio and the neighbourhood, but of the wider city via the identification of the photographer’s subjects and the recording of their stories. So far only three people have been identified.

“People think that the only aim of this project is to find these people and to tell their stories,” says El Hallak, an architect and activist. “This is of course one aspect, but so many people who don’t know anybody in the photographs still look at them and talk about the memories that they trigger. I want all these stories.”

El Hallak is consumed by the idea of Beirut’s collective memory. The belief that the city is the sum total of its people and their stories, and that maps are human, not geographic. To her the negatives are individual time capsules and photography a ‘technology of memory’. Even Beit Beirut, an architectural marvel originally designed in a neo-Ottoman style by Youssef Aftimos in 1924, is nothing without the tales of its inhabitants.

All photographs courtesy of The Delphine Darmency/Mona El Hallak Collection

Formerly known as the Barakat building, Beit Beirut was once a grand and impressive residential building made of ochre-coloured sandstone. It still has an undeniable allure, despite its infamy as a snipers’ killing machine during Lebanon’s protracted civil war. Partially destroyed and neglected in the years that followed, it largely owes its existence to El Hallak, who campaigned tirelessly to stop the building from being demolished. It has now been transformed into a museum to the memory of the city by the architect Youssef Haidar, although it remains controversially closed and largely unused.

Haidar’s revival of Beit Beirut was based on the principles of preservation, adaptation and reuse, with a new and connected building (including archival space, research facilities, auditoriums) added to the rear, while all possible traces of time, war and life in the old building have been preserved.

In total there were eight apartments in the original building, two on each floor, with each apartment built around a central hall that was itself divided into three spaces. The centrepiece of each was a triple arch with carrara marble columns.

Photo Mario’s tiny studio was located on a mezzanine level just above the ground-floor commercial space and was reached via a steep set of stairs. Less than two metres high, it had an array of curtain backdrops, some of which can be seen in the photographs that El Hallak has developed with the help of the Arab Fund for Arts and Culture (AFAC). The Arab Image Foundation assisted with the cleaning and restoration of the negatives.

Of those who have so far been identified, Dia El Turk was just two years old when his photograph was taken. He sits in front of a wintery backdrop wearing a knitted outfit and lace-up ankle-boots. He was identified by his daughter Noura during AFAC’s 10th anniversary exhibition in Beit Beirut last November.

“It’s the only one we have left in the house,” she says, showing me a similar photograph of her father when we meet at Cafe Younes in Hamra. It is almost identical, only portrait instead of landscape. “The outfit he’s wearing was knitted by my grandmother,” she adds with a smile.

“When I saw the picture it was like looking at my father’s past through my own eyes. I’m the one that lives in this country now, so it was such a beautiful parallel to see. It was very emotional. I hadn’t expected it to be.”

It is such emotion that El Hallak hopes will drive the project forward. With thousands of negatives to be cleaned, restored and potentially developed, this is a long-term commitment. Hallak even envisages a Photo Mario Cafeteria within Beit Beirut, with an additional digital platform allowing people to upload their photographs and stories. All, hopefully, will contribute to the permanent collection of the museum, creating a database of memory. “It’s like a constant exhibition of people’s portraits and a constant quest for identification,” she says.

The photographs – remnants of a bygone tradition of family portraiture – not only represent the past but are also a physical manifestation of the peculiarities of Lebanese nostalgia; that romanticised idea of a pre-war golden age and the sometimes desperate attempts to salvage it. Uncropped, with distinctive black borders, they are intimate, peaceful, serene.

“Just looking at the picture it’s like 50 years passed by in front of my eyes,” says Dia from his home in Kuwait a few weeks later. “I can still remember the street, remember the smell of the street, how we used to go to the Sanayeh Garden to play, and how the streets were empty, with only a few cars.

“What I remember mostly from that time was a different environment. A different kind of culture. Everybody knew everybody. It was so beautiful and calm and green. Not like now. We knew everybody. Now you don’t know your neighbour.”

Dia’s photograph had been taken a few days before his family left Lebanon for Kuwait in 1965. Although they would return to Beirut for the summer every year, he wouldn’t move back to the country again until 1981, a year before the Israeli invasion of Lebanon. He would come and go for the next 15 years.

“Every time I left Lebanon I used to say goodbye to everyone as if I would never see them again,” says Dia, whose family was forced to move from Ras Al Nabaa to Hamra in 1987 due to the intensity of the fighting. “It broke my heart. Lebanon used to gather people, now it separates them. I think my story is like many Lebanese. My brother in Morocco, my sister in Cairo and my daughter in Lebanon.”

Beit Beirut has consumed much of El Hallak’s life for the past 24 years. When she first entered in 1994 all of the apartments were empty apart from one: that of Dr Nagib Chemali, a dentist who was on friendly terms with Kamal Jumblatt and Abdallah El-Yafi, the former prime minister of Lebanon. She has spent the years since documenting what she found scattered on the floors – newspapers, visiting cards, letters, books, insurance policies – and piecing together Chemali’s life. The end result is a huge archive stored in her attic.

Next-door to Photo Mario was a women’s hair salon called Ephrem. The owner, who is still alive, had moved to Beirut in 1963 after winning the first prize in Lebanon’s national lottery and, with the 33,000 Lebanese pounds he won, rented the space next to Photo Mario until the outbreak of the war in 1975. He returned in 1994, painted the salon blue, and remained there until 2008 when the building was acquired by the Municipality of Beirut.

Of all the traces of the past that are still evident within Beit Beirut – patches of light cabling on the wall, broken tiles, kitchen shelving units, concrete bunkers, wooden doors, a key left hanging by a toilet window – it is arguably the graffiti that fascinates the most. During a tour of the building late last year Haidar translated much of it with an incredible attention to detail.

“The first one says ‘If the love of Gilbert is a crime, let history know that I’m a very dangerous criminal’,” he says, pointing to a cluster of graffiti on the second-floor. It is signed Tarzan Katol (Tarzan the mosquito killer). “His crime is being in love, being homosexual, and in love with Gilbert. And he considers it as a crime and he says he is the most dangerous criminal ever known, but for his love of Gilbert, not for killing mosquitoes. On the other side you have ‘Tarzan Katol was here with Gilbert’. So they were two snipers. And the third one says ‘death to Gilbert’, signed Hassoun. We met Gilbert. Gilbert is still alive, but the others are dead.”

A proverb is written on one of the walls downstairs. It reads: ‘If you watch people you die out of misery’.

Haidar’s transformation of Beit Beirut – particularly the use of steel prosthetics and the demolition of a rear service staircase – has not been without its critics, Hallak amongst them. Yet, a year-and-a-half after its completion, the building remains closed.

“For me, the Photo Mario project shows the municipality that this archive needs to be cleaned, restored and shown to the public,” says El Hallak. “It’s kind of my first step to tell the municipality, ‘do something about this building that makes the people appropriate it’.

“Every portrait has a story to tell that relates to life in the city before the war and reflects the socio-economic and demographic conditions of that time. This archive and the stories that it will bring back to Beit Beirut will reconstruct a part of our history.”

Many thanks. Great story

Sure it was😘😘

This was beautiful and poignant to read! Thank you for sharing ❤

😍😍

warms the cockles in my heart & reminds me of sitting for a photo on the pian bench with a pretend screen in back of me. Also reminds me of the Project Save, an Armenian photo saving group in Watertown MA. Thank you.

😊

Very interesting photos and accompanying text which makes this post feel so personal. It’s gratifying to know that amazing people like Mona El Hallak are devoting their lives to preserving pieces of Beirut’s incredibly rich history.

Hahaha.. Lovely

The photos are mesmerizing, I love this.

It was awesome.. Nice!!

Beautifully written and exquisitely captured. Amazing!

the complexity is elegantly portrayed. vow! (Beirut Salad)

Great post with fantastic retro pictures😘

Kaycee, watching all these black and white pictures makes me think that I traveled back in time.

Beautiful, and I can feel the poignancy of the memories. Being a Syrian, I am imagining the day when we can write about the collective memory of cities like Homs, Aleppo, or Daraa, Damascus being a whole other story. Thank you.

Thank you for sharing this moving story…it must be shared over and over

Truly mesmerizing… Reblogging this to my sister site “Timeless Wisdoms”

What fascination. It’s amazing what an old photo can evoke and express. The histories, the emotions, the context of that period and place. So much can be overlooked when we hear of a culture, a tradition or a language. Some of us have a hard time seeing any of it for what it is – a piece of the puzzle of our human existence, the journey we’re on toward a destination nobody can imagine. The collective memory, as I’ve read some place else in the depths of the inter webs, is a product of the past and future. It’s hard to wrap one’s mind around, but really, the collective memory is timeless. It’s the now. Thanks for sharing.

Very interesting way to look at the history of a city and re-build the past…

Being Lebanese and reading this warms my heart

So true, so much history is preserved with photo archives. Taking a moment to appreciate the people in the photos takes us back 50-60 years as it we are standing right next to them. I get a deep feeling of nostalgia whenever I see old photos.