OF WEDGE AND EXCESS

If the world economy is – as both logic and observation indicate – heading into involuntary ‘de-growth’, there is a choice to be made. Do we enter the era of economic contraction with a functioning monetary system available to help us manage it, and to mitigate its worst effects? Or do we sacrifice monetary viability in a futile effort at denial?

The former might be a great deal more rational, but probability increasingly favours the latter.

The coronavirus pandemic has not so much created as accelerated tendencies towards the use of financial expansion as a cure-all for both real and imagined economic ills. This puts two facets of monetary observation into conflict. On the one hand, we know that fiscal and monetary stimulus can help us to moderate economic downturns. On the other, though, we also know that too much monetary intervention carries the risk of undermining the all-important credibility of fiat money.

If ‘too much debt’ is one risk, ‘too much monetization of debt’ is another, and both seem to have gone into overdrive since the start of the coronavirus crisis. SEEDS data and estimates indicate that, during 2020, a group of sixteen advanced economies (AE-16) are likely to have run fiscal deficits of about $8.8 trillion, or 20% of their combined GDPs, a figure pretty much matching the $8.9tn that the four main Western central banks deployed in net asset expansion (QE) during the year.

Even if vaccination does indeed quickly bring the pandemic under control, continuing fiscal intervention – and the need to alleviate burdens placed on lenders and landlords by debt and rent payment ‘holidays’ – imply further big increases in public debt, and central bank monetization, during the current year.

Does this put the viability of fiat money itself at risk?

It’s certainly starting to look that way.

Not measured, not managed

Part of the problem is that orthodox economic interpretation cannot quantify what “too much” monetary intervention actually means. In the absence of such calibration, the authorities are at the mercy of short-term thinking and political pressures. Accordingly, those who express dark forebodings about the fate of fiat in a context of unprecedented financial intervention may very well be right.

The original intention here had been to concentrate wholly on monetary issues. But the better plan is to locate the role of money within broader economic processes, and then to ask whether there can be better calibration of the concept of monetary “excess”.

The conclusion reached here is that we can use energy-based measurement of prosperity as an independent benchmark against which to measure the economic claims embodied in the financial system. This measurement indicates that we have already travelled too far down the road of creating excess claims to turn back without making enormous, hugely unpopular adjustments to the system.

As the old saying goes, “if it isn’t measured, it isn’t managed”. This describes our current monetary predicament very well indeed – if credit creation and monetary policy seem out of control, the lack of meaningful measurement is a major factor in what has become an unmanaged problem.

The inability of monetary measurement to calibrate “excess” in a meaningful way is a consequence of the use of equations whose components are not discrete (that is, they are not independent of each other).

The often-used ratio which compares debt with GDP is a case in point. If, for instance, additional credit is put into the economy, the effect is to increase the economic activity that is counted as GDP, meaning that both the numerator (debt) and the denominator (GDP) are inter-connected. Indeed, and in situations where the debt/GDP ratio already exceeds 100% – where, that is, debt already exceeds GDP – it is perfectly possible for a rise in the quantity of debt to cause a fall in the ratio between debt and GDP. This results in a systemic underestimation of the proportionate extent of debt, a process of understatement which becomes more pronounced as indebtedness increases.

In this knowledge vacuum – in which the term “excessive” cannot be defined – decision-makers find it very hard to resist pressures for ever more fiscal and monetary intervention. Those urging support, whether for their own sector or for the economy as a whole, can call in aid Keynes’ observations about stimulus, omitting to add that the Keynesian calculus addresses the smoothing of cycles, not a perennial stimulation of economic activity on a continuing basis, and envisages periods of financial tightening which offset periods of stimulus.

As remarked earlier, it’s likely that fiscal stimulus injected into sixteen Western economies totaled 20% of their combined GDPs last year, and may be of the order of 10% in 2021, with the former number essentially monetized by central bank money creation. This, on the face of it, looks like “excess”.

So at what point, then, does financial intervention become “excessive”? Conventional ratios such as debt/GDP cannot tell us this, and neither, in a market distorted by huge intervention, can interest rates answer this question either. Another non-discrete measure – that which compares asset prices with liabilities – cannot help us to know where the “point of excess” lies. For various reasons – which include the conventional exclusion of asset prices from the calculation of inflation – we can’t even rely on inflation numbers for warning that the point of excess looms.

A claim on energy – the real meaning of money

To understand these issues, we need first to place money in its economic context. Conventional explanation ascribes three roles to money. One of these is as store of value, a function which fiat currencies cannot, historically, be said to have fulfilled. A second is that money can be used as a unit of measurement, but this, as we’ve seen, is an extremely flawed concept, primarily because there exist no recognized non-monetary benchmarks against which monetary numbers can be measured. This leaves us with the third – actually, the all-important – function of money, which is as a “means of exchange”.

Of “exchange”, though, for what? Clearly, the only meaningful process of exchange is one which involves the use of money to buy goods and services. This in turn defines money as a ‘token’. As such, money has no intrinsic worth, meaning that it commands value only in terms of the things for which it can be exchanged. This is why, in Surplus Energy Economics, money is defined as a ‘claim’ on goods and services.

Money can usefully be likened to the ticket or ‘check’ given to a person handing in a hat or coat when attending an event. Printing more of these checks doesn’t increase the number of hats or coats available when the exchange process is reversed at the end of the function. Likewise, the ‘check’ cannot, of itself, keep its owner warm or dry – for this, it needs to be exchanged for an actual (physical) coat or hat.

With due apologies to those who already know this, the role of money as claim is one of the three core principles of the surplus energy economy. The first of these is that all of the goods and services which constitute economic output are products of the use of energy, such that nothing of any economic utility whatsoever can be supplied without it. This defines money as a ‘claim on energy’, with the corollary being that debt, as a ‘claim on future money’, really functions as a ‘claim on future energy’.

The second core observation is that, whenever energy is accessed for our use, some of that energy is always consumed in the access process. We can’t put oil to use without drilling a well or building a refinery, access gas without investing in wells and processing systems, make use of coal without excavating a mine, or harness solar or wind power without constructing solar panels, wind turbines and distribution systems. All of these processes are themselves functions of the use of energy. The “used in access” component is known here as ECoE (the Energy Cost of Energy).

This enables us to refine our definitions, such that money is ‘a claim on surplus (ex-ECoE) energy’, and debt ‘a claim on future surplus energy’. A logical question to ask ourselves is: what has happened to money, debt and broader obligations, in relation to surplus energy, in recent times?

Comparing 2019 with 1999, and using financial data adjusted for inflation, money GDP expanded by 95%, and debt by 177%, over a period in which global surplus energy increased by less than 50%. Throughout this period, these ratios became progressively worse.

What this means for underlying economic output, and its relationship with debt, is illustrated in the following charts. Since the mid-1990s, aggregate global debt (shown in red in the left-hand chart) has expanded far more rapidly than reported GDP. The central chart shows how, expressed at constant 2019 values, annual borrowing (in red) has been far larger than increments to GDP (blue).

The right-hand chart shows how the development of a ‘wedge’ between debt and GDP has inserted a corresponding wedge between reported GDP and underlying or ‘clean’ output (C-GDP).

This interpretation is wholly ignored by orthodox approaches, which fail to recognize the connection between the non-discrete (that is, the connected) entities of debt and reported GDP. Properly understood, though, the ‘wedge’ concept can provide important insights into the way in which the interaction between debt and GDP distorts both the real level of economic output and the extent of leverage built in to the system.

Prosperity as process

The identification of ECoE divides the supply of energy into two components. One of these is the cost element (ECoE), and what remains is surplus energy. Since this surplus energy powers all economic activity other than the supply of energy itself, surplus energy is coterminous with the material prosperity delivered by the economy. If monetary measurement of the economy departs in any meaningful way from this definition of prosperity, we can be said to be practicing financial self-delusion.

Though ignored by orthodox economics, the ECoE process is reasonably well understood. In the early stages, ECoEs are driven downwards by geographic reach, economies of scale and advances in technology, with the proviso that the scope of technology is circumscribed by the physical characteristics of the energy resource. In the case of fossil fuels – which continue to supply more than four-fifths of global primary energy consumption – the potential of reach and scale has been exhausted, introducing depletion as the primary (and upwards) driver of ECoEs. The meaning of depletion is that, quite naturally, we have used lowest-cost sources of oil, gas and coal first, leaving costlier alternatives for a “later” which has now arrived. Technology can mitigate the ensuing rise in ECoEs, but cannot overturn the laws of physics such as to push ECoEs back downwards.

This has always meant that the end of fossil-fuel-powered economic growth wasn’t going to be a matter of “running out of” oil, gas or coal, but of encountering rising costs (ECoEs) which erode the economic value of each unit of energy accessed. Cost and volume parameters are interconnected, of course, so that rising costs must inevitably, in due course, result in decreasing volumes.

The great hope, reinforced by urgent environmental imperatives, is that we can replace rising-ECoE fossil fuels with falling-ECoE renewable sources of energy (REs). Imperative though the development of RE capacity is, some of the more glib assurances of seamless transition have always been something of a triumph of hope over analysis.

There are two main snags with the ‘seamless transition’ thesis. The first is that, though falling, the ECoEs of REs might never fall far enough to replace low-ECoE fossil fuels as drivers of economic expansion. The second is that, because RE expansion relies on inputs whose supply depends in turn on the use of fossil fuels, we may not be able to de-link the ECoEs of REs from the (rising) ECoEs of fossil fuels.

REs are already close to offering ECoEs that are competitive with, or below, those of fossil fuels today. What we require of REs, though, are ECoEs that replicate the ultra-low levels of fossil fuels, not now, but in their heyday. For reference, SEEDS analysis indicates that prosperity in the advanced economies turned down at ECoEs of between 3.5% and 5%, with the same happening to less-complex, less ECoE-sensitive emerging market (EM) economies in an ECoE range between 8% and 10%.

What we require of REs, then, are ECoEs that are certainly less than 5% and, ideally, ECoEs which replicate those of fossil fuels – between 1% and 2% – back when oil, gas and coal were capable of driving real and sizable increases in material prosperity.

The reality, though, is that it seems unlikely that the ECoEs of REs are ever going to fall much below about 10%. On that basis, the global economy – with an overall trend ECoE of 9.3% – has already entered a phase of deteriorating prosperity, a trend from which not even EM countries such as China and India can be expected to be exempt.

We can call this process “de-growth”, but with the proviso that this is not the voluntary contraction advocated by those who contend that the world would be a better place if we ditched our obsession with material “growth”. Rather, what we’re experiencing now is involuntary “de-growth”, imposed upon us by a deterioration in the energy equation which determines trends in prosperity.

Where reported GDP – inflated both by credit effects and by a failure to allow for ECoE – exceeds prosperity, the situation is one in which we are creating “excess claims”. Simply stated, this means that financial behaviour is creating (and distributing) monetary claims that the surplus energy of today and tomorrow will be incapable of meeting. If that’s the case, the destruction of the “value” contained in these “excess claims” becomes inescapable. To revert to an earlier metaphor, a lot of people are going to present ‘checks’ for which no economic hat or coat exists for the purpose of exchange.

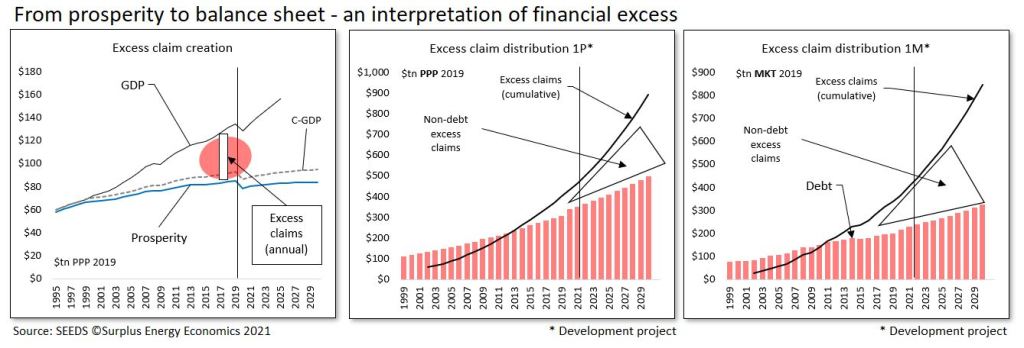

The following charts set out the “excess claims” interpretation of the relationship between prosperity (measured on an energy basis) and financial ‘promises’.

The left-hand chart illustrates the process by which reported GDP has departed from underlying prosperity. Whilst monetary expansion has – as we have seen – driven a wedge between reported (GDP) and underlying (C-GDP) output, the inclusion of rising ECoEs tracks a further divergence between C-GDP and prosperity.

The result is that a steadily widening divergence between GDP and prosperity has created successive annual increments of excess claims within the financial representation of the economy.

It must be emphasized that the central chart reflects ongoing development work on the SEEDS model. This project has reached a point at which we can produce a realistic illustration of the cumulative build-up of ‘excess claims’ over time. In the chart, this is set against global debt to show how the accumulation of excess claims has progressed far beyond the relatively straightforward expansion of debt, and now embraces many other and substantial forms of liability.

The left-hand and central charts are calibrated in international dollars PPP – this is the preferred convention in SEEDS, and converts other currencies into dollars on the basis of purchasing power parity. To facilitate comparison with debt and other statistics, the right-hand chart shows the global equivalents of debt and excess claims on the basis of market dollars.

Greek Tragedies; Socrates; Democracy; Regrowth; Russia and the US; Orlov

In comments above I, and others, have noted that democracy is not a guarantee of effective action in double bind situations. Here is a short excerpt from Dmitry Orlov’s current post (behind his pay wall):

“Russia doesn’t need political opposition and is naturally trending toward the Soviet baseline defined by the slogan “The people and the Party are one!” The US is also trending toward single-party rule, with the Deep State Democrats in complete control and the Republicans running for cover in fear of being prosecuted as domestic terrorists. This is probably as it should be, because an existential global crisis calls for unity of purpose and is not a good time for opposition and indecision.”

That brings to my mind Joe Biden’s decision that the entire government automobile fleet will be converted to electric drive. Is that smart or stupid? Is the best bet to shut up and do something, or should we have debates? Will it all be decided by lobbyists regardless of what the public thinks?

Don Stewart

PS. Alice Friedemann thinks we are well on our way to “Wood World”. Among other things, we will be unable to manufacture motherboards. Is it all ‘Much Ado About Nothing”?

Given that there is no future for electric cars on a large scale, as clearly and in all detail demonstrated, for example, by Simon Michaux (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n_gvvj56rzw), I would say it is mostly “symbolic“. “Smart or stupid” is perhaps not applicable here. But if he believes it makes any real difference, I would say it is stupid.

“They claim to be super-patriots, but they would destroy every liberty guaranteed by the Constitution. They demand free enterprise, but are the spokesmen for monopoly and vested interest. Their final objective toward which all their deceit is directed is to capture political power so that, using the power of the state and the power of the market simultaneously, they may keep the common man in eternal subjection.”

Henry Wallace, 9 April 1944

Gloom and Doom and a Grasp at a Straw

Dave Pollard has an interesting take on humans and our inability to deal with complex predicaments…from Covid to the financial bubble:

https://howtosavetheworld.ca/2021/01/29/covid-19-and-human-incapacity-to-deal-with-complex-predicaments/

“No one is to blame for that, as much as we’d love to assign it. The reality is that no species is competent at addressing complex predicaments — there are too many moving parts and variables, and no mechanism for coordinated decision-making and action beyond the smallest, local level. “

I would like to add a caveat…it all turns on the ’mechanism’…or lack thereof. If we look at neuroscience (through the lens of Lisa Feldman Barrett’s and others’ work), we find that humans are driven to do what they consider in their own best interests. But on closer examination, we find that the term ’their own’ is flexible. For example, many parents will risk their own life to save a child. A group of unrelated people can, with good leadership, sacrifice their own narrow short term interests for the larger interests of the group. For example, much of military training is designed to persuade individuals who did not formerly know each other to function as a group (e.g., a rifle squad). A key ingredient in the persuasion is the notion of fairness coupled with the notion that ‘if we don’t hang together, we will all most assuredly hang separately’ (attributed to Benjamin Franklin re the rebellion against King George).

IMHO, the lack of perceived ‘fairness’ is at the root of the disintegration of the US and the larger efforts to avoid ecological disaster. Just as a matter of interest, the latest measurements indicate that the ability of Earth to sequester carbon in biomass and oceans has peaked, or will peak very soon, and Earth will begin to put carbon back into the atmosphere. Can you find anyone who believes that dealing with this ‘fairly’ has any prospects?

It is said that the establishment of the IPCC was deliberately manipulated by the US and Britain to maintain their hegemony…’fairness’ would have implied redistribution and the leaders in the US and Britain wanted none of that.

I’m not really optimistic that, at this late date, the US or Britain will be able to reconstruct faith in the fairness of the political machinery. I won’t speak for other countries. But it is a straw that we might grasp at.

Don Stewart

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/amp/business-55849898

Being green is not black and white.

That’s according to the man who runs the world’s biggest money management firm. BlackRock manages nearly $9tn (£6.6tn) of pension and investments.

“If we all ran away from the hydrocarbons and everything, and if you ran away with most of those companies in the FTSE [100], the job loss in the United Kingdom would be extraordinary. Is that the outcome that they want?” he told the BBC.

When the pandemic hit, investors ran to the hills. They dumped their share holdings and turned them into cash. The Dow Jones index of the biggest companies in the US lost 10,000 points, or nearly a third, in a matter of days.

The stock market has rebounded as investors look hopefully to a post-pandemic world – their moods enhanced by enormous amounts of emergency financial drugs such as money printing, and massive government borrowing and spending.

It has proved irresistible for governments around the world to promise they will “build back better” – it may also prove hard to resist the yearning to return to what we had before – and if cheap oil, for example, helps us do that, then so be it.

…..

If QE is finding its way to hydrocarbon investments, via ‘passive funds’, then this explains how the rising ECoE is being passively subsidised by monetary stimulus which in turn is helping to increase energy production/consumption.

https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/per-capita-energy-use?tab=chart&time=earliest..latest&country=~OWID_WRL®ion=World

We need to be a little cautious about this, because trades in the secondary market don’t raise money for companies – funds are only raised when new shares are sold to investors, or where stock is used as a means for acquiring assets.

More broadly, though, loose monetary policy certainly helps finance fossil fuel activity – as has been demonstrated, prior to the shale crash, by the large amounts of equity and debt capital used to finance the shale boom.

Thanks Tim

I have just read a well written article that pretty much sums up my own view in blog called “Consciousness of Sheep”.

“……..The closer we get to the edge of the Seneca Cliff, the faster the political class will reach for projects that are designed to drive us over the edge. The various bits of the Green New Deal which are adopted will rapidly run into resource shortages. This will result in the first serious supply-side shock since the 1970s. The result will be far greater stagflation than was experienced in that benighted decade. And this time around there will be no North Sea, Alaskan or Gulf of Mexico oil deposits to bail us out.”

https://consciousnessofsheep.co.uk/2021/01/29/the-great-train-wreck/

In my opinion, his time scale is just about right too.

“…….One day – maybe tomorrow; maybe five years from now – sterling will lose its value as the final, diehard investors realise the debt is never going to be repaid.”

Although, if I were very cynical, I might think that the various Central Banks have long since formed an unofficial concert party to buy each other’s government debts based on monies printed and then loaned to each other. Additionally, of course, the above could just as easily apply to the Euro or the US Dollar.

@Gavin Thornberry

Yes….and…

Take a look at Alice Friedemann’s last two posts at Energy Skeptic, which describe the almost unimaginably complicated manufacturing processes involved in chips and motherboards. What has been happening is increasing complication, increasing cost of the factories, and a shrinking numbers of factories.

Given the overall scenario you have laid out, one wonders whether it would be desirable, and possible, to revert to a simpler world of motherboards and chips? My suspicion that such a simpler world would cause a reversal of the miniaturization trend…with far reaching consequences.

Don Stewart

Yes, that’s a good article, though I see no reason to assume that other currencies couldn’t be described in similar terms.

Neither would I confine consideration to debt. A broader measure worth referencing is financial assets. Latest numbers show these at 500% of GDP worldwide, and more than 1100% of GDP in the UK, as of end-2019. Back in the GFC, these assets – largely the counterparts of liabilities – rose sharply, and we can probably expect the same to happen again.

Then there are pension gaps. Back in 2015, the WEF put these at $67tn for eight countries, and projected an increase to about $430tn (constant) by 2050.

Most of these numbers are referenced to GDP. But, as we know, GDP (a) includes the effects of buying $1 of “growth” with $3 of new debt, and (b) ignores ECoE. Rebase any of these numbers to prosperity and far higher ratios result.

At the moment I’m trying to calibrate some measures of global financial liabilities, in addition to the SEEDS metric of excess claims.

But the conclusion is bound to be that liabilities are (a) almost incomprehensibly vast, and (b) measured against false metrics of affordability.

The implication seems to be that runaway inflation cannot now be avoided. The ironic thing about “reset” is that this might have been possible (but was ducked) back in 2008-09. It isn’t feasible now.

For the Sterling bears, this just out:

https://www.marketwatch.com/articles/the-pound-is-ready-to-emerge-from-years-of-darkness-says-ing-51612284926

My technical guru’s momentum system has a 3 year target of near $US 2. I know it sounds crazy.

I’d be interested to know what the same analysis says about – for instance – the Australian dollar and the Chinese renminbi – in other words, is this a case of GBP rising, or USD falling?

The momentum model has Sterling stronger than the Euro, Yen, & AU for the next few months. I’ll check about Renminbi. It does have the $US weakening in general for a few years.

To me, a rising GBP is counter-intuitive in the context of fundamentals, events and exposure……

@Dr. Morgan

Disclaimer: If I were a prophet, I would be rich…and I am not rich.

That said, I find it very difficult to combine my views of the fundamentals (e.g., degrowth and dysfunction) with the obvious ability of the monetary authorities to swing huge amounts of resources around in the economy. See Wolf Richter’s analysis of the US housing market and the stock market, as examples. The obvious demand driven inflation being created in manufacturing supply chains as well as the transportation sector. Several commenters have predicted that zero interest rates will destroy the meaning of money and time…and that seems to be what is happening. How can people blithely pay 3 times more for a house in Los Angeles when their real incomes are falling? (Of course, they are only promising to pay over a very long number of years.)

Don Stewart

Given ready supply of credit (which the authorities have, thus far at least, ensured), property price levels move inversely with interest rates. Rates have long been unsustainably low, and credit supply has been boosted by covid intervention. So there’s nothing surprising about property price inflation.

Ultra-low rates do indeed condemn economies to financial bubbles which, unless they are burst – not much chance of that course being chosen – will destroy the value of money.

Wizard of Oz

I guess I keep expecting Dorothy to look behind the curtain and see a pathetic old man manipulating the dials.

Don Stewart

Prospects for Managed Reset

In the US, the mass delusions make me very pessimistic about the prospects for any managed reset. For a blow by blow description of the melt-down in Washington, see this New York Times article:

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/31/us/trump-election-lie.html?

The US political system needs two parties which oppose each other on many points, but are able to compromise. I suggest that the ground for the Right Wing anger has been laid by the reality of Degrowth plus the actual wealth effects of the monetary adventurism since 2007 plus the bedrock conviction resident in many Americans that we are Exceptional…as in God’s chosen people. The trigger was the election of an extreme narcissist who was also very clever and very determined. The result is that a little less than half of Americans believe anything they hear which confirms their beliefs or suspicions. All the Democrats who bought into the ‘Russian collusion’ story was scary enough. Now, I believe it is virtually impossible for a Republican to win a primary without appealing to the extreme right wing. Since the sort of Neoliberalism that was fueled by favorable ECoEs and abundant natural resources controls the Democrats, and Trumpism controls Republican primaries, (both of which are delusional)….what genius politician can make it all work to bring us “a prosperous way down”?

Don Stewart

Part of the problem Don is billionaire’philantrophists’ who seed fund political movements and activist groups.

https://www.spiked-online.com/2021/01/29/the-billionaire-takeover-of-civil-society/

These networks actively homogenise the narrative hence the ground swell of delusions about Russian collusion. In other words, brainwashing at a national and international scale.

This billionaire funded gaslighting was merely copied by Trump.

Don, can you give a link to the NYT article, please?

Justin

the link that was in my post works. But here it is

UPDATE

I think we’ve now reached the point where SEEDS can calibrate the cost of essentials. This means that we can measure discretionary prosperity, and compare it with actual discretionary consumption. So far, this project is confined to the 16 Advanced Economies covered by the model.

The conclusion is perhaps best summed up by the title that I might use if/when I write this up.

That provisional title is Dead Sectors Walking.

Essentially, as and when we can no longer inflate activity using monetary adventurism, discretionary consumption will slump. What we’re witnessing is that de-growth, whilst it continues to allow us to afford essentials, is taking away the scope for non-essential consumption.

I love the provisional title!

Agreed on the title!

The same compression which destroyed Retail and Hospitality is now strongly observed in Energy and Chemicals.

My expectation is that we are in for a Nominal price shock in those two sectors, but that will not lead to General Inflation…….it will only accelerate and mostly destroy the rest of the economic activity…….

It will be a scene to watch…….

Mark this post.

@Steve Gwynne

Yes….and…

The billionaires definitely have an agenda. For example, take a look at Ugo Bardi’s current web site. He has recently had 5 posts censored by Facebook, which has 3 billion eyeballs looking at it.

We used to think that what the social media wanted was eyeball counts. Now they are much more sophisticated, and want ‘engagement’. Which means you are a little bit enraged, but not so enraged that you think that another beer won’t solve the problem. Bardi’s Seneca Cliff approach is not a ‘little bit enraged message solved by a beer’ message.

Part of the difficulty, from a Societal Survival viewpoint, is the tendency to form in-groups and out-groups. For example, if you show white people in San Francisco two pictures, one with all white people and the other with all black or brown people, they immediately identify with the white people and that identification has measurable results in terms of subsequent actions. But if you show them one picture of white and black people wearing San Francisco Giants T shirts and another of a similar group wearing LA Dodgers T shirts, then they identify with the Giants fans, regardless of skin color, and their subsequent actions carry the traces of that identification. Anybody who understands the basic mechanism, or can hire scientists or PR people who understand the basic mechanism, can use the knowledge to manipulate crowds of people. In Politics, all it takes is someone who puts himself or herself absolutely first and is willing to do ‘whatever it takes’. The same is true of corporation chiefs or even Little League coaches.

We in the US are fortunate that Trump was not able to run over the Deep State (much maligned though it is). When he tried to use the power of the Justice Department to get the result he wanted, they threatened mass resignation. We were lucky, and can give a nod to some perceptive people who set things up to make it more difficult for dictators.

Don Stewart

Re: “the billionaires have an agenda,” see Tim Watkin’s latest, “Trading Safety for Peace of Mind,” at Consciousnessofsheep. Their “agenda” is a fairy tale they tell themselves to buy peace of mind that their way of life will continue.

Re: the “social science experiment” you cite above, I find it to be unconvincing junk. What the heck does “identify with” mean? Sounds like circular reasoning to me. Claptrap like this is no guide to anything.

@Jeffrey Snyder

I took the anecdote from Robert Sapolsky at Stanford. He is, among many other accomplishments, the author of the book Behave, about human behavior.

As far as ‘identification’ is concerned, you may be interested to learn that a study just published shows that mice are able to identify with other mice through the same circuits that humans use for empathy.

Don Stewart

A couple of reading items which tie in to Dr. Morgan’s estimate that we are out of runway in terms of discretionary spending.

First is Gail Tverberg’s current article, in which she comes down in favor of collapse:

“Instead, plans for a Great Reset tend to act as a temporary cover-up for collapse.”

Second is a paper by a Swedish academic on the subject of Emergy, as developed by Howard Odum and others:

https://www.academia.edu/38014985/Why_is_emergy_so_difficult_to_explain_to_my_ecology_and_environmental_science_friends?

I will point out one similarity between Gail and Odum in terms of Emergy: the concept of an energy hierarchy. Energy from a different level of the hierarchy is not necessarily very useful at some other level of the hierarchy. For example, the enormous amount of energy absorbed and then emitted every day by the worlds oceans isn’t very useful for moving a load of sand or gravel. Gail makes a very sharp distinction between wind and solar and fossil fuels as being in different levels of the hierarchy, with wind and solar not being very useful for many of the industrial processes we use (such as making chips and motherboards, as we know from Alice Friedemann’s recent posts). I wouldn’t say that movement between levels of the hierarchy is impossible….it’s really an engineering question or a lifestyle question. We are all familiar with engineering, so I’ll suggest that a lifestyle featuring passive retention of body heat with layers of clothing is a substitute for natural gas heating of the whole house. But we should recognize that such a change in lifestyle destroys segments of the economy. Thus, we might say that a substitution which involves moving to a lower strata in the hierarchy will usually destroy the wealth created by the complexity afforded by the higher strata of the hierarchy. A seamless transition is likely not in the cards.

Don Stewart

Working out the cost of essentials, in order to arrive at discretionary numbers, has been pretty tricky. The definition that I’m using is “things that the average person has to pay for” – that is, these are ‘first calls’ on incomes that the person has to pay for, whether he or she likes it or not.

This defines essentials as (a) household necessities, plus (b) government spending on public services. You or I might not think that a new high speed rail line or a squadron of F35s are “essential”, but they qualify in my definition because the citizen has to pay for them. This does not include pensions, welfare and similar, because these are transfers between people, not purchases (on our behalf) of public services. I hope to explain this with greater clarity when I write this up.

On this basis, discretionary prosperity is already falling relentlessly. Discretionary consumption has carried on rising. The difference between the two is funded by credit.

This poses some tricky choices. We can’t, for the most part, reduce the costs of household necessities. We might, as societies, vote to spend less on public services, but much of this would still have to be paid for, whether by the citizen or by the government.

Where this leaves us is that, if we do ever stop pushing credit into the system, consumer discretionary sectors will slump. If, on the other hand, we don’t stop monetary expansion, fiat currencies will lose their value.

Do we want to lose things like leisure, travel, consumer gadgets and similar – and the jobs that go with them – or do we want see the dollar, euro pound and other currencies lose value, towards a point of ultimate failure? These hard choices are the product of involuntary de-growth.

Essentials and Kris DeDecker

To the papers by the Swede and Gail Tverberg, I might add all the clever ways to do things using less energy that have been explained over the years by Kris DeDecker. For example, it is necessary to keep the Dutch canals dredged. Historically, the canals were dredged by hand by canal keepers who lived in houses immediately adjacent to the canals. Kris lived in the same circumstances for a year or so and measured how much work he had to do with a hand dredge to keep the canal operational. It turned out to be feasible.

That is an example of substituting a lower hierarchical source of energy (food) for a higher hierarchical source of energy (industrial machines powered by fossil fuels). Of course, what would happen is that the canal keepers would have very limited ability to pay for vacations to tropical islands, taxes paid would be very low, and the industrial economy devoted to keeping the canals operational would shrink to the making of hand operated dredging tools.

Kris used some Dutch paintings from centuries ago to illustrate the use of layers of clothing rather than industrial heat (which I stole for my previous note), plus people crowded together in small rooms to get the maximum heat retention (which was illustrated in the picture).

Now it occurs to me that both the debt expansion AND the substitution of lower hierarchical sources of energy result in the destruction of the value of money created by debt, which we can measure as reduction in real GDP.

Don Stewart

Am catching up, so forgive if already covered. Re:

“This does not include pensions, welfare and similar, because these are transfers between people, not purchases (on our behalf) of public services.”

In the US,Canada, and I believe some other developed countries, large pensions are privately funded. (IRAs, Keoghs, Corporate & Institutional ones) US Social Security has not been mainly a transfer, as deductions from paychecks occur from the first one. Employers also kick in, but that is a business expense and built into prices. Now that the actuarial stats show payouts exceeding inputs, it seems to me that transfers are an increasing %.

so even if I cut my discretionary spending to the bone and renegotiate my essential spending to be as minimal as possible I’m unlikely to be able to influence the ‘essential’ spending the govt. is making on my behalf in the form of HSR & F-35’s,

I do rather feel like a hostage on a runaway train,

Exactly!

And, since they don’t understand the underlying issues as we understand them here, it’s likely that they’ll carry on doing so until the debt/money system topples over.

A random observation out of my window recently while watching a utility company digging up a bit of road. There were at least 5 guys there at any one time, and 3 work vehicles, the small digger, the removal van for the rubble and another with new kit to go in the hole. Additionally, there were about 3 vehicles the workers used to get to the site themselves. Most of the total activity involved was in digging then filling up the hole and at that time 4 watched the 1 operating the digger machine while waiting to do their parts.

At first I marveled at how there was a neat machine to do what seems like every manual action necessary these days, then realised the difference between now and before ‘affordable fuels’, is you still had 5 guys and the job was also done in a day, but without the massive expenses of fueling the workers to and fro, the machines functioning and their manufacture. So is it really an advance other than being a better quality of life for the manual laborers who would all have been digging all day like navies back in that era?

A lot of tasks today aren’t even more time-efficient, just more wasteful in the environmental destruction mining the resources for the machinery and fuels. In some respects, simplifications many not reduce quality of life meaningfully, possibly it could even balance out in that we’d be healthier having to do physical activity daily in less pollution. Obviously sophisticated medical equipment is worth hanging onto for as long as the remaining resources can be stretched out for.

I have observed the same thing. Small hole dug and filled near me by the gas company took about 3 weeks, a fleet of vehicles and work machines, also resulted in a multi-car pileup (apparently a rubber-necker taking a look). 60 years ago I was doing highway construction work and used a lot of pick and shovel (I was young and strong back then).

Don Stewart

Where I used to live, the electricity board closed and dug up the street to install a new cable. In the process, they connected a live cable to a neutral (or whatever), destroying a lot of appliances. Then they filled it in……..

…..and then came back and dug it all up again because they’d forgotten to put in the new cable!

interesting piece linked from the Automatic Earth site today highlighting the drop in US births since 2008,

https://ifstudies.org/blog/5-8-million-fewer-babies-americas-lost-decade-in-fertility

couple that with the recent uptick in excess deaths caused by covid and you see population being squeezed from both ends,

I’ve been tracking excess deaths here,

https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/static-reports/mortality-surveillance/excess-mortality-in-england-latest.html

Here’s a gem from the BoE, via the BBC:

“Bank of England: Economy to rebound strongly due to vaccine

………..policymakers expect a rebound in the spring as people become more confident about spending.”

Yes, but spending what? Money they’ve borrowed? Or money given to them in stimulus by a government which, in turn, borrowed it in huge amounts?

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-55934405

The article claims “ due to the vaccination” the economy will grow.

Surely we will still be paying off the cost of the vaccines ( never revealed as far as I am aware) out of the debt we currently have. Also it states rather oddly that reduced foreign travel will somehow be an economic downside. Since the expense of foreign travel would mainly pass into the coffers of other nations it does not seem like a necessary element of a growing economy . I doubt that foreign tourists to the UK are going to be appearing in droves in view of the abysmal COVID outcome on the UK.

What they mean by “growth” is spending – irrespective of where the money spent comes from. The UK is a prime example of a credit-dependent economy (and the US is another). The BoE seems to have ruled out – for now – negative rates, but rates are already negative in real terms, meaning that people (and businesses) are paid to borrow. The “Anglo-American economic model” has become a long-winded term for “idiocy”.

Still catching up. BOE came out with an alert to banks and others on the possibility of negative rates in the future.

Tim, thanks for the link to the BBC item. When you read the entire article, it struck me that the BOE is in fact sitting on the fence. It really does not know where we are headed. My sense is that there are large parts/sectors of the economy which are in dire straits and that is before the anaesthetic of furlough has worn off. Also how can those sectors even begin to revive when the Government now seems committed to a medium-term strategy of shutting the economy on no notice when (and it is when) new more-vaccine-resistant variants of Covid arise?

Aside from the fact that we may well have reached the point of “credit exhaustion”, I sense a general sense of exhaustion in the UK at the moment. We are shut in our homes, the weather is poor, people are bored.

I have just taken my office post to the Post Office and, like on other days in the last few weeks, there was quite a queue of people waiting to mail their small packets of stuff they have sold on-line to someone else; One chap was proudly posting 10-15 packets and said “I must have made £15 on that lot” – lord knows how much time he spent and what the jiffy bags cost – he went on to say that he needs the £15 “towards the electric bill”, which is rather a worry.

Others I work with are just exhausted with home working and, particularly, home schooling, for those with younger children. I just saw this in The Guardian: –

“Employees who work from home are spending longer at their desks and facing a bigger workload than before the Covid pandemic hit, two sets of research have suggested.

The average length of time an employee working from home in the UK, Austria, Canada and the US is logged on at their computer has increased by more than two hours a day since the coronavirus crisis, according to data from the business support company NordVPN Teams.

UK workers have increased their working week by almost 25% and, along with employees in the Netherlands, are logging off at 8pm, it said.

NordVPN Teams analysed data from its servers to see how private business networks were being used by employees working remotely.

Separate research shared with the Guardian by the remote team-building firm Wildgoose found 44% of UK employees reported being expected to do more work over the last year, with those at mid-sized firms most likely to report an increased workload….”

The mental health of society in general has deteriorated a great deal, methinks, and it is slowly dawning on people that they will be poor in retirement as their pension options diminish.

Some are past redemption. I spoke with a man who “owns” two houses nearby. He lives in one with his wife and his in-laws, who are elderly and frail, in the other. He called me as he had just received a letter from his bank in connection with his mortgages. These were once conventional capital & interest repayment mortgages, but, some 15 years ago, he converted them to interest only “because it saved me money each month”. I assumed that he had save the difference between the two loan repayment amounts; of course, he had not, but spent it on “stuff”. So, this man, who will soon be 65, owes his bank £550,000 in a few month’s time. He has “equity” in the two houses of about £100,000 and minimal savings and investments. I’m afraid I said he had behave recklessly and was in danger of becoming homeless (sure, equity release might help, but I rather doubt it). So, these four individuals have ended up in a very precarious situation; if this is being repeated on any scale, there will be huge difficulties, very soon.

Hi Tim, thanks for the well-written article summarizing your thoughts over the past few years. I have questions that linger in my mind regarding economics i.e. what is the end purpose of economics? Is it a rationing system to fulfil the basic needs (housing, food, education, healthcare) of the citizens? My hypothesis is, in an ideal world, if we issue food ration for everyone, we could feed all 7 billions people with not much issue with our current production system. The same could be argued for housing, education and, maybe stretching it a bit, healthcare. Think of it as the global welfare system.

Even if the “excess claims” become worthless in the future, as long as the current production (machines & people) remains online, we should be able to avert a societal collapse.

I understand the ideas about SEEDs, ECOE and the impending de-growth, but, in my opinion, doesn’t the main issues lie with distribution of the ‘claims’ and the management / production of the essential services?

@RPM

Your scenario assumes multi clan, multi tribe, and multi nation cooperation. Those have been rare exceptions in the history of H. rapacious-superstitious. While it is theoretically possible, to expect it to obtain is highly speculative in my view.

The dollar has tumbled 13.1% from its high last March, thanks in part to historic moves by the Federal Reserve to pump liquidity into the financial system and pull down American borrowing costs. While policy makers abroad at first benefited from U.S. action to stave off a global credit crunch, the appreciation of their currencies more recently threatens to curtail their own recoveries. So from Europe to Thailand to Chile, officials have laid out plans for sustained intervention.

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-01-28/yellen-faces-currency-war-redux-as-she-ditches-a-strong-dollar

Presumably a weaker dollar is good for US exports but bad for non-US exports, hence interventions.

The question is whether a self organising global economy of state actors can continually intervene with monetary stimulus and remain balanced.

Probably not so an international compact will probably be forthcoming.

I think that the ultimate Fate of Fiat is already cast, it will explode in a hyper-inflationary bust.

All Fiat will go at the same time, the US$, the Eur, the Yen and the GBP.

For the time being they are all propping each other up, by buying each others debt, but the question is: how much longer will the rest of the producing world tolerate this. Nobody has really got a vested interest in bringing the system down, but they are all very gingerly removing their pieces of Jenga while they still can. Eventually the last piece to stability will be removed.

And that is when the real fun will begin.

Admittedly, I have been reading Alasdair McLeod over on Goldmoney.com and I have been swayed by his arguments of impending currency collapse.

Most people are awaiting a strong rebound in the post-Covid economy, planning luxuries like holidays and haircuts, I try to tell them that there is no post-Covid economy and that what we are facing is a post-Covid economic depression.

I often get accused of being a pessimist, but I think I am being realistic. Although I can imagine most hairdressers re-opening their businesses, I really do not see how the Airline and travel business is ever going to come back from this. Especially when we have climate change activists cheer-leading the industry’s demise.

I think there are a couple of points of note where the fate of fiat is concerned.

First, as prosperity falls, so does the ability to afford discretionary consumption. If a person’s income is declining, he or she may still be able to afford the essentials, but the ability to pay for non-essentials is decreasing. This person then has a choice between (1) reducing discretionary purchasing, or (2) using increasing debt to carry on with discretionary purchasing at (or even above) previous levels. At the macro level, the choice has been made to do the latter – support discretionary consumption using credit expansion.

Second, monetary policy determines the relationship between (a) asset prices (stocks, property and so on) and (b) incomes (including wages, dividends, rents and interest income). We’ve chosen to distort this relationship in ways which boost asset prices. This doesn’t add value, because we cannot, by definition, monetise the entire stock market, or the entirety of the housing stock. So what we’ve done is to inflate notional value by distorting the asset price/income relationship. This had happened even before 2008, but has become even more extreme since then.

Taken together, here are the choices that we’ve made. First, we’ve chosen to put the real value of money at risk by using ever-expanding credit to prop up discretionary sectors. Second, we’ve accepted – and/or welcomed – the inflation of notional asset values created by this policy of ultra-cheap money.

This policy mix only works if one believes that (a) ‘we can never create too much credit’, and (b) ‘we can never create too much money’ (these are coterminous, of course). To believe this, one must also believe that the economy is a purely monetary system, to which no external constraints (resources, environment, etc) apply.

My view is that such constraints do apply, and I believe that both evidence and logic support this view. If this is right, then the policies we’ve been following must – if we persist with them – destroy the purchasing power of money.

If we put together various components, we should be able to map this process. These components include: prosperity (and therefore ECoE); the scale of monetary claims on the economy, and the scale of ‘cumulative excess’ within these claims; the cost of essentials, and the residual of discretionary prosperity; and the handling of relationships between these components, liabilities and notional asset valuations.

It seems to me that we’ve got this mix wrong, perhaps because the process isn’t understood because of the exclusion of non-financial benchmarks from our interpretation of economics. This is at its worst in Britain and America. China, on the other hand, might well ‘get it’. If this is the case, then the balance of global influence is tilting, not because blind fortune, the ‘march of history’ or something equally esoteric favours China over the Anglo-Americans, but because of a superior level of understanding on the one side, and inferior understanding on the other.

Off-topic here, but for zeitgeist purposes, there’s a favorable article in The Sun on Collapsologists in the Welsh countryside and the collapsology movement.

https://www.the-sun.com/news/1074573/collapsologists-civilisation-crumbles-coronavirus-preppers-prepared/

The situation in the UK is surreal. The MSM falls into two camps: those that are predicting and promoting a post-pandemic economic boom, and those that recognise a country of two halves – some have survived very well, an awful lot are barely surviving at all. Even if one steps aside from SEE and SEEDS and look at traditional economic measures, we’re running a triple deficit, we have to import huge quantities of food and energy and we’re into the thirteenth year of SFP – Severe Financial Repression – with evidence suggestive of failing fiat. Colne is a northern former mill town, about 30 miles north east of Manchester, and I can report that the public infrastructure is in a truly dreadful state, people look beaten and worn down, yet locally the political class continue promising rainbows and unicorns. The breadth and depth of political delusion and denial is simply off the scale.

It really isn’t much different in Somerset, Kevin, just hidden away from prying eyes. I live in a village of about 1,350. I guess at least a third in retirement; they have the nicer homes. Because they loaded the system in their favour, with defined benefit pensions and lower costs of buying a house (relatively so). Their middle-aged children and grandchildren are almost trapped on a wearying treadmill of earning to service debt and just get by. Some of them, at least.

Worrying times indeed if you are skint.

Tim Watkins has just added an article “The other side of the story” to his blog -“The consciousness of sheep”. It relates to the energy quandary we face . This quandary is just as serious as the economic one. Sadly we educated more PPE students than thermodynamics students in the last half century.: the consequences of which we are now reaping

That reminds me of the statistic that US colleges produce 44 lawyers for each engineering graduate.

Fragility

Alice Friedemann today at her Energy Skeptic blog:

“They (microchips) are the pinnacle of human achievement, the most complex objects on earth, requiring fabrication plants costing billions of dollars, need the most pure chemicals and air of any product, the most vulnerable to electric outages, and supply chains, and will therefore be the first industry to fail when energy shortages become common.”

Most of our stuff simply won’t work without microchips. Even fiat money is now completely dependent on microchips. So I suggest that this is a subject worth thinking about.

Don Stewart

Fiat; Microchips; Something Else

Nora Bateson said in a tweet:

“The system cannot change the system.”

Hard to imagine that a world utterly dependent on microchips can invent a world without microchips. Some historical systems have collapsed when people just walked away (e.g., the classic Maya) but now the world is much more crowded and where would we walk to? It seems to me that the world can survive the collapse of fiat (Germany did, Zimbabwe recently), but microchips are much more fundamental than money.

Don Stewart