Like many people this week, I have struggled to get my head around wearing a mask when I go out shopping. For a start, there are so many small considerations, such as when to actually pull the mask up to the mouth and when to lower it. A whole new social etiquette is emerging which I’m finding in some ways amusing and in other ways confusing.

Yesterday, an encounter in a coffee shop amused when the manager offered a plastic visor to an elderly couple, who had forgotten their masks, to try on for size. Even though I was masked, I was also offered a turn so that I could agree that the plastic shield bearing the breath droplets of strangers was far superior to my own cloth model.

The confusing part involves how to speak to people when they can’t see your mouth. Rather than offer a muffled ‘morning’ which seems superfluous now that my accompanying smile cannot be read is it perhaps better to offer a nod instead?

In Born to be Good, a fascinating study on human behaviour, social psychologist Dacher Keltner, devotes an entire chapter to the significance of the smile His research dissects the different types of smile human animals offer to each other. One classic example is the ‘service industry smile’ ‘the one that signals the customer is always right’ and masks the frustration of workers who must never show their feelings no matter how unreasonable the demands made by the one being served. This smile creates such strain Keltner observes as to ‘produce a form of schizophrenia.’

“We may experience feelings of emptiness and quiet frustration, or a deep ennui, but we display to the world the smile of satisfaction.”

Dacher Keltner Born to be Good (2009)

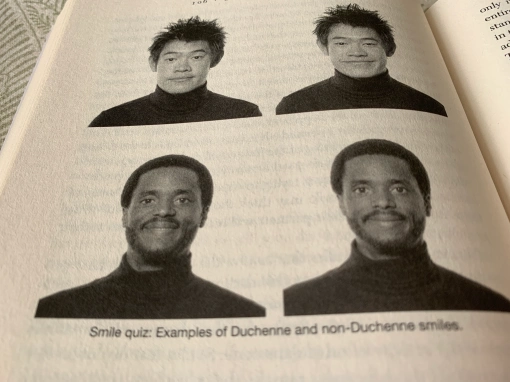

There are many different occasions when people smile and Keltner’s research has shown that people smile while exposed to the most unlikely situations, for example, after losing and when watching a film of an amputation. But the emotion behind the smile differs according to which muscles are activated. Smiles which activate the delightfully named ‘happiness muscle’ or the orbicularis oculi tend to last longer and communicate genuinely positive states. These smiles have been named Duchenne or D smiles after the French neuroanatomist Guillaume Benjamin Amand Duchenne (1806-1875). If the happiness muscle does not fire, smiling still happens, but does not last as long and often masks a negative state. These non-Duchenne or non-D smiles might be anxious or nervous smiles or smiles to cover up the true emotion.

This research shows that it really is true that we smile most fully with our eyes, which is good news for those who feel that the full range of emotions has been muted by the necessity of wearing a mask. Interestingly, because only the eyes can be seen it might make it easier to read the genuineness of a smile.

Here’s Keltner on how you tell if it’s D or non-D: when contracted, the muscle around the eyes, raises the cheek, pouches the lower eyelid and wrinkles the skin into crow’s feet – the most visible sign of happiness. ‘People may think they look prettier following Botox injections, but their partners will receive fewer clues to their joy, love and devotion.’

So, the next time I’m shopping along with my fellow mask wearers and we’re all eyeing each other as we try to navigate this strange new social landscape, I must remember to look for the crow’s feet.

In the example above, taken from Born to be Good, which is probably one of the funniest works of psychology I’ve ever read, the D smile for the first gentleman, is on the right; for the second, it is on the left. Of course, you all got that, didn’t you?

Leave a comment