A Problem Outlined

There’s often a great ready-made true English word which could be used instead of the fancier form: can for to be able to, for example. Indeed, when we put can and to be able to next to one another, we might wonder why anyone ever says the latter.

I can speak English or I am able to speak English…

However, forms like to be able to get support by being able to seep into territory that the true English words cannot. For example, we can also say “I will be able to” or “I may have been able to”, but we cannot say “I will can” or “I may have could” — at least not in standard varieties of English! Or what about the word absorb? Why not simply say soak (up)? Oh yes, that’s because we can readily say absorbent and absorbency, but we cannot so easily form the related adjectives and abstract nouns from to soak (up): upsoakingness? Yes, upsoakingness is possible (and I quite like it, actually), but it arguably doesn’t sound like an extant English word. For that reason it draws attention to itself and thus discourages its own use.

Forms of the Problem

As you can see, there seem to be two forms of such “seeping”:

(1) defective true English words which cannot be used in all contexts where an Englandish word can be;

(2) related concepts where no such form exists in true English, but it does for the Englandish root.

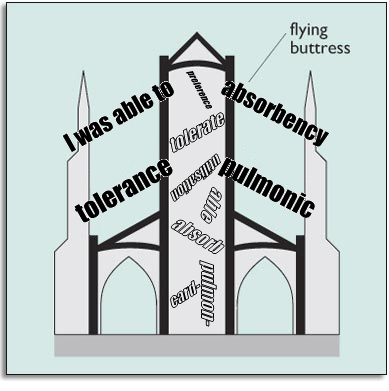

The existence of forms like (1) may have been able to and (2) absorbency, means that unneeded and un-Anglish words like to be able to or absorb are given extra support and periodically revitalised by association with may have been able to and company. Indeed, utterances such as I am able to speak English are thoroughly buttressed and stopped from ever falling down — despite their ungainliness.

Causes of the Problem

This is unfortunate, and seems to be the result of a few things, including:

1. Defective or unclear English morphology: lung (noun) –> ?lungish (adjective); *upsoaking: adjective or abstract noun or verbal noun or verb?

2. A hesitancy in English, relative to other Germanic languages, to put prepositions at the beginning of a compound: ?upsoakingness.

3. Heavy use of phrasal verbs which, firstly, have been shunned historically as uncouth and thereby discouraged, and secondly, are not wont to form derivatives (see “2”): tolerate –> tolerance and put up with –> ?put-up-with-ness…

Part of this problem has been caused by the influx of outland words into English. If we’d never gone so gungho down this borrowing path, we would likely have remained as German and Swedish have, and therefore not have this problem. There would, of course, be the odd time where due to natural process within the language, we would have to borrow a form: I don’t know if we can blame the ungrammaticality of I might have could on the word-borrowing fetish of the English language.

Solutions?

- Use non-standard forms like I might have could unflinchingly and without remorse.

- Come up with slightly uncouth forms like upsoakingness — again, unflinchingly and with no remorse — but make sure you aren’t being too clever for your own good. The Anglish Moot, which I helped set up, has some great work on it — and also some of the overclever stuff I am talking about (such as umbethinking).

And that’s all for today, folks…

What!? But it can’t be! Where’s the inspirational ending and summing up?

Well, it seems to me that so long as Anglishers are aware of the problem I’ve outlined in this post, they will be more sensitive to not just oversetting stand-alone words, but rather to taking words as being members of families or groups of words used in many contexts. It’s not enough to simply say, “don’t say to be able to, say can instead” because we simply can’t say can a lot of the time! We need to be attacking the problem holistically, as well. Words exist in the context of other words, and many unfit words are supported by the buttress of far more useful, yet merely derived, words or phrases (such as would have been able to).

featured image by Bryan A. J. Parry edited from image at http://passport2design.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/flying-buttressdiagram-batuhijauschool.org_.jpg

© 2014 Bryan A. J. Parry

[…] of the principles of my Saxon English or “Anglish” project is the concept of “buttresses“. Just as a buttress stops a building from falling down, some words act as buttresses which […]

[…] note that preface as a noun is probably buttressed by the use of preface as a […]

[…] talk about the concept of word buttresses. That is, words or phrases or usages which support less strong words and prevent them falling out […]

[…] The fairly useless word “collaborate” looks like it’s being buttressed by these two words, as well as by the negative, traitorous sense. Indeed, perhaps […]

[…] used, they stay well-known owing to their use in the Bible. These words are, as I put it, “buttressed” by their familiarity as part of scripture. Here are some other homeborn words from the same passage […]