By: Jefferson P. Webb

Introduction

Normally when researching a topic for steelfighting.com or engaging in other scholarly activities, it is recommended and I typically always adhere to utilizing multiple sources for an article, book, or paper. In this particular posting though I have found one primary source that I have found so very valuable that I have used it exclusively here. That source is authored by Chevalier Geoffroi De Charny, and is entitled, “A Knight’s Own Book of Chivalry.” While I have used his book as the only work of literature as a source, coupled with my own experiences and views on the matter of chivalry, which I might add are very much in line with De Charny’s beliefs, this posting is not a book review. Likewise this posting does not come close to covering the many details De Charny gave in his book and I highly recommend purchasing a copy and reading the book if this is a topic that interests you. I find it to be an authoritative work on the topic of chivalry. We at steelfighting.com hope you enjoy this brief look into the topic of chivalry and what it meant in the Medieval period, and furthermore we hope you enjoy reading De Charny’s work should you choose to do so.

Normally when researching a topic for steelfighting.com or engaging in other scholarly activities, it is recommended and I typically always adhere to utilizing multiple sources for an article, book, or paper. In this particular posting though I have found one primary source that I have found so very valuable that I have used it exclusively here. That source is authored by Chevalier Geoffroi De Charny, and is entitled, “A Knight’s Own Book of Chivalry.” While I have used his book as the only work of literature as a source, coupled with my own experiences and views on the matter of chivalry, which I might add are very much in line with De Charny’s beliefs, this posting is not a book review. Likewise this posting does not come close to covering the many details De Charny gave in his book and I highly recommend purchasing a copy and reading the book if this is a topic that interests you. I find it to be an authoritative work on the topic of chivalry. We at steelfighting.com hope you enjoy this brief look into the topic of chivalry and what it meant in the Medieval period, and furthermore we hope you enjoy reading De Charny’s work should you choose to do so.

It has been said many times in recent decades that, “Chivalry is dead.” By the standards of contemporary ideas of what it means to be chivalrous, it may not be dead, but hanging onto life by sparsely dispersed threads throughout our societal fabric. Our modern idea of what it means to be chivalrous, passed on to us by our Victorian predecessors,1 are not only a small portion of what actual chivalry was in the Medieval and Renaissance periods, but we find it rejected by the very people today for whom such acts of kindness and respect are offered. Nevertheless, if our contemporary idea of what it means to be chivalrous is only part of the story, what is chivalry?

In seeking the answer to the question of what chivalry truly is, it would initially appear that we would need to travel back in time, find a medieval knight and then ask him to explain chivalry according to the practice of it in his lifetime. Obviously such a thing is not possible, but we are blessed to still be able to read a remarkable primary source that gives the reader deep insight into what it meant to be chivalrous during the zenith of the Age of Chivalry. What is so special about this work, “A Knight’s Own Book of Chivalry,” is that is was composed for knights by one of the most celebrated knights of Medieval Europe, Chevalier Geoffroi De Charny (c1306-1356).2 Furthermore, chivalry was the code by which De Charny lived and died.

In seeking the answer to the question of what chivalry truly is, it would initially appear that we would need to travel back in time, find a medieval knight and then ask him to explain chivalry according to the practice of it in his lifetime. Obviously such a thing is not possible, but we are blessed to still be able to read a remarkable primary source that gives the reader deep insight into what it meant to be chivalrous during the zenith of the Age of Chivalry. What is so special about this work, “A Knight’s Own Book of Chivalry,” is that is was composed for knights by one of the most celebrated knights of Medieval Europe, Chevalier Geoffroi De Charny (c1306-1356).2 Furthermore, chivalry was the code by which De Charny lived and died.

When reading De Charny’s book, De Charny quickly lets the reader know what is ultimately the key ingredient of chivalry, and that ingredient is prowess.3 Prowess is essential in chivalry because it is the chief means by which a man-at-arms earned honor, and to be chivalrous one had to be honorable. So, the means by which one earned honor was by actions taken utilizing his prowess. It is very interesting to note that according to De Charny’s beliefs of honor earned through prowess, that he believed in differing degrees of honor based on the different types of activities in which the knight used his prowess.4 The activities that De Charny describes in relation to this are related to deeds of arms. He stated in his descriptions in order of least to greatest in the types of honor earned, but stated that he believed no deed of arms was small and all deeds are worthy of honor.5 He stated that the first was the joust, meaning one on one competitive sporting combat be it mounted or on foot. The next elevated level of honor was the tourney, meaning melee competitive sporting combat where groups of knight (teams if you will) fought other groups. Finally of the greatest level of honor was that earned in actual war.6 De Charny went further and described the different subgroups of these levels of honor earned in different types of war.

We also find in the study of chivalry through De Charny’s, “A Knight’s Own Book of Chivalry,” that while prowess forms the chief trait of chivalry, there are other aspects of conduct, some of which the modern person can perhaps related to much better. Honorable and chivalrous men-at-arms, De Charny stated should, “Conduct themselves properly and pleasantly, as is appropriate for young men, gentle, courteous, and well-mannered towards others, who have no desire to engage in any evil undertaking…”7 In this quote we can clearly see something more recognizable to what the modern person calls to mind when hearing the term, “chivalrous.” This conduct was not only to be directed towards ladies as is commonly believed, but was to be displayed to all people, friend and enemy alike. There was to be great honor in deeds of arms, but there too was to be honor earned from one’s treatment of others in daily life. Nevertheless, as gentlemen were indeed to treat their ladies in the manner stated above, the lady also had her roll in chivalry. According to De Charny her chief roll was to further inspire the prowess of her knight by her own love for him and confidence in him.8 She was to support him in his desires for competitive events and in the event of war. Through her inspiration and support the knight should have even greater prowess and thus earn greater honor through his actions in deeds of arms. This in return was to bring greater honor upon the lady for whom the knight was associated with (either married or otherwise) and greater admiration of her by her peers.

What can we conclude that chivalry was in the age of chivalry from De Charny’s views as one of the world’s most celebrated knights of Medieval Europe? We can certainly come the the conclusion that chivalry was not j ust a code to live by, it was a warrior’s code by which he earned honor and reputation. It was the code that, if followed by a knight according to De Charny, would bring him great honor and celebration through feats of courage on the battlefield and competitive fields of festivals. It was a code of honor that, if followed, in theory would have kept a knight honest and trustworthy, loyal and faithful to his fellow knights, to his liege, and to his lady. It was a code to live by and a code to hold true to until death as did Chevalier Geoffroi De Charny to his death in the Battle of Poitiers in 1356 at the hands of the English. Truly it appears that Chevalier Geoffroi De Charny was a knight who believed strongly in the Code of Chivalry while living in the Age of Chivalry, and while we may be living in an age that in many ways is quite different from that of the 1300’s, we are likewise not so different.

ust a code to live by, it was a warrior’s code by which he earned honor and reputation. It was the code that, if followed by a knight according to De Charny, would bring him great honor and celebration through feats of courage on the battlefield and competitive fields of festivals. It was a code of honor that, if followed, in theory would have kept a knight honest and trustworthy, loyal and faithful to his fellow knights, to his liege, and to his lady. It was a code to live by and a code to hold true to until death as did Chevalier Geoffroi De Charny to his death in the Battle of Poitiers in 1356 at the hands of the English. Truly it appears that Chevalier Geoffroi De Charny was a knight who believed strongly in the Code of Chivalry while living in the Age of Chivalry, and while we may be living in an age that in many ways is quite different from that of the 1300’s, we are likewise not so different.

Certainly in contemporary times in the United States as well as many of our allies’ nations, we view military service to our nations as honorable. When a person serves in the armed forces of their nation they are engaging in modern day deeds of arms, be it peacetime service, wartime service in a support fashion or in actual combat. Perhaps they compete in marksmanship competitions or martial arts competitions within the services. These are deeds of arms worthy of honor. These military personnel in their service and their honorable deeds of arms are thus chivalrous. Furthermore to support this observation as fact, it takes prowess to be a member of the military. Clearly there are occupational fields that demand much more prowess than others, but in the end, all require some level of prowess to venture into. While we typically all view such service as an honorable thing, and we also tend to view people of whom display good character, display respect, kindness, and generosity towards others as honorable, somewhere along the way over the centuries we have failed to maintain the connection between the two. Chivalry has typically been looked upon as opening the door for a lady (a sign of respect and not a sign of superiority), assisting someone in need even if it means some level of sacrifice be it large or small, or by observation of perhaps those unwritten rules in competitions that are viewed as gentlemanly in nature. It is much more and De Charny did well to define chivalry and describe it in all of its intricacies for his fellow knights, and for those of us living in the twenty-first century.

De Charny, Geoffroi. A Knight’s Own Book of Chivalry. PA: University of Pennsylvania Press 2005. 2

De Charny. A Knight’s Own Book of Chivalry. 1

De Charny. 22

De Charny. 22

De Charny.

De Charny.

De Charny. 47

De Charny. 66

Bibliography:

Geoffroi De Charny. A Knight’s Own Book of Chivarly. Trans. Elspeth Kennedy. Philadelphia, PA. University of Pennsylvania Press 2005.

Pitcures:

De Charny Coat of Arms. http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geoffroi_de_Charny Accessed 7-23-2012

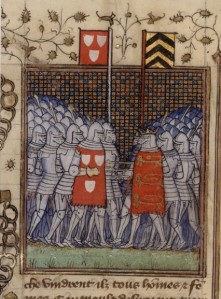

De Charny and Edward III. http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geoffroi_de_Charny Accessed 7-23-2012

Battle of Poitier Death of De Charny: elgrancapitan.org. http://www.elgrancapitan.org/foro/viewtopic.php?f=87&t=16834&start=240 Accessed 07-10-2012