To be a prominent player in one unfashionable team that kicks, mauls, gouges and intimidates its way to huge overachievement might be seen as an accident of circumstance. If it happens a second time, with a different club and in a different country, then it’s no coincidence: it’s a habit.

To be a prominent player in one unfashionable team that kicks, mauls, gouges and intimidates its way to huge overachievement might be seen as an accident of circumstance. If it happens a second time, with a different club and in a different country, then it’s no coincidence: it’s a habit.

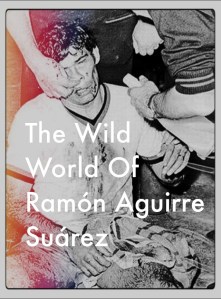

Ramón Aguirre Suárez was a footballing pariah with a lengthy charge sheet of vicious excess from his Estudiantes de La Plata days (Read Part One of this story) In the second part of his tale we take a look at his equally turbulent time in Spain with Granada. Welcome back to the Wild, Wild World of Ramón Aguirre Suárez.

Ramón Aguirre Suárez was a footballing pariah with a lengthy charge sheet of vicious excess from his Estudiantes de La Plata days (Read Part One of this story) In the second part of his tale we take a look at his equally turbulent time in Spain with Granada. Welcome back to the Wild, Wild World of Ramón Aguirre Suárez.

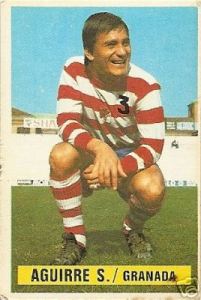

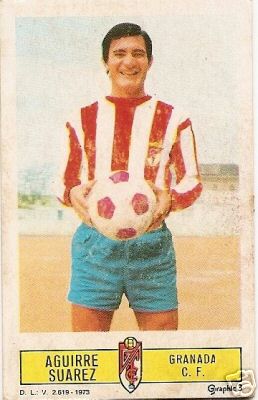

Leaf casually through the Spanish League Panini album for the 1971/72 season and you might chance upon the sticker of one particular player, a defender who looked powerfully built but otherwise undistinguished. His picture shows him looking slightly off-camera and smiling broadly as if sharing a joke with a teammate on a sunny day.

It’s a sticker that doesn’t seem particularly distinct from any other, except this one was portraying no ordinary player and the joke he appeared to be enjoying was ultimately to be on Spanish football. This grinning assassin was the reviled Argentinian defender Ramón Aguirre Suárez, football’s wildest player and the vicious anti-hero of the successful Estudiantes de La Plata side that had brutalised club football for the past half-decade. A pariah figure on two continents, his reputation for relentless and remorseless violence was legendary and now, for reasons very few people liked nor could even understand, he had pitched up in an obscure corner of southern Spain ready to play for the newly promoted Granada club.

An appalled Spanish press took no time in castigating him as an “animal,” an “assassin,” and a “killer” who would “disfigure the Spanish game.” These headlines were delivered with little sense of irony, Spanish football in the early 1970s was itself no place for the shy and retiring type. Uncompromising as it might have been, the difference between Spanish violent and Aguirre Suárez violent was akin to the difference between hurting an opponent and hospitalising him.

No Spanish player had ever been jailed for his actions on the pitch; Aguirre Suárez had been detained on two occasions. No Spanish player had caused the advancement of pioneering plastic surgery reconstruction techniques; Aguirre Suárez did when he shattered the cheekbone of Milan striker Nestor Combin with frightening force in the World Club Cup Final of 1969.

There were legal as well as moral objections too. Foreign imports had technically been banned by the Spanish Federation since 1962, though Granada was just one of a number of clubs exploiting a loophole that allowed the signing of uncapped South Americans capable of proving Spanish lineage. Proper records were sketchy though, so South American agents would happily supply fake documentation to push through deals. Producing paperwork to prove a familial link to Pamplona was an easily surmountable hurdle for Aguirre Suárez, claiming he had never represented Argentina in a full international match was a harder one for critics to swallow – he was after all a three-time South American club champion. He claimed to have been called up but only to attend training camps, but no matter anyway as all that was needed was a small bribe to acquire the necessary confirmation to this effect from a compliant official back home.

So, thanks to the bullishness of ambitious Granada President Don Candido Gomez, the transfer was pushed through for a modest fee – albeit one that still represented a club record. A pompous and abrasive character, Granada’s President claimed the deal as “Spain’s most important signing of the season.” He had a young squad and reasoned that he needed experienced players like Aguirre Suárez as a stabilising influence. The player himself was charm personified as he politely answered questions from the press about his reputation. Their questions were, in reality, just one, single question asked many different ways about his boundless capacity for violence.

“I like to play strong but have never shown treachery or been in trouble with another player” he stated. “When on the field I defend my team with justice, I’m an honest and responsible player.” Stirring stuff indeed from a master of the disingenuous – this was a player known to assault injured opponents as they received medical treatment after all.

He was ready to debut in the third round of the championship against Español and his off-field smiles and platitudes were quick to be forgotten. Any prospect that he was likely to temper his scorched earth approach was quickly dispelled as he launched two-footed into his new career with relish. His first thirteen appearances yielded an unprecedented five bookings – this in an era when you could commit half a dozen brutal fouls before the referee would even think of booking you. Those were the fouls that the referee saw of course as Aguirre Suárez had forgotten none of his tricks and remained the master of sly, cunning assaults calculated to hit when the referee’s attention was elsewhere.

It was no coincidence that his career had shown a pattern of prominent performances in games against the biggest, strongest clubs. The psychology originated from his Estudiantes days and the logic made perverse sense – the bigger the gulf in quality between you and your opponent, the greater the need to intervene and diminish their advantage by whatever means possible. The gulf between little Granada and the four giants of the Spanish game in Real Madrid, Barcelona, Valencia and Atlético Madrid was huge, thus it made perfect sense to Aguirre Suárez that these were the matches that necessitated his most extreme interventions.

Games between Granada and Real Madrid proved especially volatile. In their first encounter, relentless fouling by Aguirre Suárez pushed mild-mannered Madrid legend Amancio to breaking point. The final straw was a thuggish knee-high assault on the veteran by the Argentinian’s partner in crime Fernando Fernandez, a vicious Paraguayan full back. With both players on the ground, Amancio retaliated by kicking Fernandez in the head and causing a bench-emptying brawl. Standing well away from the ensuing chaos with his hands on his hips was Aguirre Suárez. As was so often the case, he had been the instigator but stood back when things boiled over and let others take the punishment. Amancio and Fernandez were both sent off, the latter on a stretcher.

Within half an hour of a match against champions Valencia he put opposing striker Claramunt in hospital, much to the fury of their coach Alfredo Di Stefano. The fouling continued throughout the second half and each time he assailed a Valencia player, he would turn to the touch-line and wave or blow kisses at the opposition bench. In his report, the referee supervisor wrote that Aguirre Suárez should have been sent off within the opening 10 minutes, yet he collected only a booking. Others came off worse as usual: the referee was suspended and a volcanic Di Stefano fined for trying to attack his compatriot at the end of the game.

Controversy continued to plague his debut season. Promising 21-year-old Real Madrid striker Carlos Santillana was gaining rave reviews for his elegant forward play, at least until his progress was violently curtailed in the Granada return fixture. Santillana was repeatedly kicked by the Granada central defender, but showing commendable bravery refused to be intimidated away from the opposition penalty area. Perhaps tiring of the young Spaniard’s belligerence, Aguirre Suárez coldly ended his involvement in this game and football at large for the next three months with a jaw-fracturing, elbow to the face.

The Argentinian was methodically intimidating and often injuring his way through the list of top centre forwards in Spain, just as a contract killer works through a list of assassination targets. Atlético Madrid strikers Garate and Luis both came off worse in encounters and the club complained vociferously about their treatment at his hands. Barcelona’s strikers fared little better with Marcial and Asensi both left battered and bruised. Asensi was quoted as saying: “playing in Granada is like going to war.”

Granada was the most penalised team in Spain and yet this approach yielded results despite the unpleasant methods underpinning it. Their debut season back in the top division saw them finish in a highest-ever sixth place, all achieved on the back of an unbeaten home record that included memorable wins against all of the big four. Their Los Cármenes stadium had become a fortress: a citadel of intimidation with Aguirre Suárez the anti-hero provocateur-in-chief and darling of the home fans. History was repeating itself and once again a limited, but organised team with Aguirre Suárez at its fulcrum was overachieving thanks to a calculated, brutal amalgam of cold logic and hard violence.

His success led to a demand for better financial terms and a clash with the Granada president with whom he had a complex and ambivalent relationship. While publicly Candido Gomez blithely defended his player from the perpetual criticism his appalling behaviour brought, privately he was irked at his popularity with the home supporters who saw him, and not the President, as the reason for their success. Partly because of this jealousy and partly through injury, the Argentinian was frozen out of the first-team picture for most of the 1972-73 season. Perhaps not surprisingly Granada never looked as effective and finished in a lowly thirteenth position.

Relationships were repaired and the Argentinian was back in favour for the 1973-74 season with a welcome-back gift from his President of a new, like-minded partner in central defence. Julio Montero Castillo was a talented but feral Uruguayan arriving from Nacional with his own mean reputation and Aguirre Suárez knew him well as an old adversary from Libertadores Finals past. As an intimidatory statement of intent, it could not have been more successful. The rest of Spanish football took a sharp intake of breath and surveyed a back line that was a compendium of horrors, featuring as it did the most notorious players that Argentina, Uruguay and Paraguay – Fernandez was still a regular – could offer up.

Di Stefano had consistently been Aguirre Suárez’s biggest critic and he proposed his own solution to the problem when deciding that he would field youth players in matches against Granada, so as to avoid risking the limbs of his Valencia stars. The other big sides followed suit: Cruyff did not turn out for Barcelona, Netzer did not play for Real Madrid. Granada results were strong once more and another sixth-placed finish was secured thanks to just a single home defeat. Granada had developed from a team that kicked the big names out of games to one that barely had to – the big names were too scared to even turn out against them.

Aguirre Suárez was not offered new terms when his contract expired in 1974 and he reluctantly left the club. He stayed close to the fans however and remained a regular visitor over the next few years, sometimes even watching games from the bench as the team declined rapidly in his absence. He signed for newly promoted Salamanca, but played only three games there before returning home. In 1977 he came out of retirement to play four games for Lanús and then remained linked to football, coaching teams in Tucumán and working in schools in the La Plata area.

When interviewed in later years he proved to be an entertaining and disarming interviewee who spoke with humour and an unabashed lack of remorse about the excesses of his playing days. For him the ends always justified the means; he posed the question how else his teams could have achieved the success they did without the brutally fundamentalist approach that defined them. For him the notion that the particular price of this success might have been too high to pay was utterly incomprehensible. Of the threats, the violence and the intimidation he said: “We were constantly playing or preparing and only had family contact every three weeks. As a team we shared a roast together but nothing else. Where else would we get our fun?”

When interviewed in later years he proved to be an entertaining and disarming interviewee who spoke with humour and an unabashed lack of remorse about the excesses of his playing days. For him the ends always justified the means; he posed the question how else his teams could have achieved the success they did without the brutally fundamentalist approach that defined them. For him the notion that the particular price of this success might have been too high to pay was utterly incomprehensible. Of the threats, the violence and the intimidation he said: “We were constantly playing or preparing and only had family contact every three weeks. As a team we shared a roast together but nothing else. Where else would we get our fun?”

The 1960s and early 70s had seen a culture shift towards increasingly cynical methodology, but the footballing authorities remained mired in outdated attitudes of supposed Corinthian values and acceptance of old-fashioned physicality. They were slow to react to the new threat that players like Ramón Aguirre Suárez had brought and he was adept at taking advantage of this disconnect. How could you separate out his football from his intimidation in an era where a game would be watched by a single black and white camera and referees were amateur, poorly protected and often neither fit, nor smart enough to keep a grip on powerful athletes with malevolent streaks? He was a player who was simply ahead of the rules and he knew it.

The era spawned many hard men who realised they too could forge decent careers for themselves by virtue of forcing the submission of more talented opponents, yet still, Aguirre Suárez stood apart from his peers and copyists. Few had the same range of physical and psychological weapons in their arsenal, few were as cunning in their deployment and few were mentally strong enough to face down the huge outcry their behaviour caused without tempering their approach. It took nothing less than jail sentences handed down by Argentinian Presidents to temporarily slow Ramón Aguirre Suárez in his tracks. Ultimately no other player was prepared to go just quite as far as he did for a cause, and none appeared quite so utterly and ruthlessly devoid of empathy for the welfare of his fellow player.

There is a reported story of a young forward about to kick off a match against Granada. Aguirre Suárez beckons him over and tells him: “Bambino, you must play on the wings because today the centre is your Vietnam.” No story could better encapsulate this monster of a man.