Siniša Malešević is a Professor of Sociology the University College, Dublin and Senior Fellow and at CNAM, Paris. His recent books include Grounded Nationalisms: A Sociological Analysis (Cambridge UP, 2019), The Rise of Organised Brutality: A Historical Sociology of Violence (Cambridge UP, 2017) and Nation-States and Nationalisms: Organisation, Ideology and Solidarity (Polity Press, 2013). His publications have been translated into eleven languages.

People who do not believe in conspiracy theories find the conspiratorial thinking ridiculous or bizarre. The conspiracy theorists are often deemed to be psychologically unstable, gullible, or delusional. Several psychological studies have indicated that individuals who strongly believe in conspiracies have schizotypal personality disorder and tend to infer meaning and intention where there is none. In a recent experiment on the behaviour of inanimate objects schizotypal individuals would regularly attribute intention and motivation to the randomly moving triangle shapes on a computer screen (Hart and Graether 2018). While identifying a psychological profile can help us understand the frame of mind of a typical conspiracist this research tool is inadequate for explaining conspiracy theory as a mass phenomenon. When conspiracists remain on the margins of society they can be dismissed as psychologically unstable or paranoid. However, when millions of individuals start believing in conspiracies and when this interpretative frame becomes a dominant social discourse then psychological accounts will not suffice.

Conspiracies in the Yugoslav Space

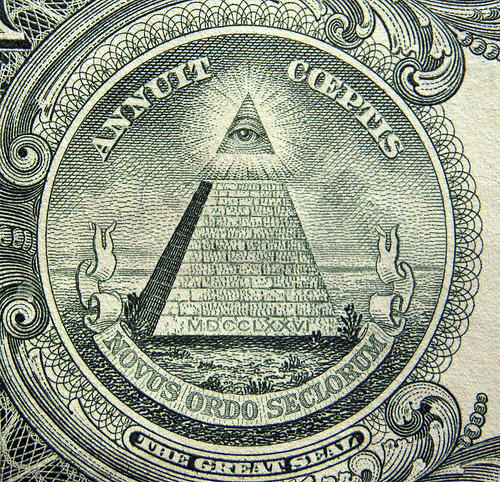

In the late 1980s and early 1990s Yugoslavia has experienced such a dramatic interpretative shift. The gory break-up of the federal state was preceded and also followed by sudden proliferation of various conspiracy theories including the ideas that the state was intentionally dismembered by Vatican, Free Masons, Jewish Lobby, CIA committed to build the New American Order, the Islamic powers bent on establishing the Green Transversal linking the European Muslim populations with Turkey, the united Germany aiming to create the Fourth Reich, and so on. The population which in the late 1970s and early 1980s was for the most part indifferent to the conspiratorial thinking has suddenly become highly receptive to this interpretative frame. Hence the conspiracy theories started permeating the public and private sphere. They were present in the intellectual debates, mass media reports, political and religious events, and the mass demonstrations. They also featured in the personal conversations between friends and family members. Although the conspiracy theories invoked different and often mutually exclusive narratives and diverse plethora of threats and enemies, they all congregated around one common theme – our (ethnic) nation is in danger.

Hence the Serbian conspiracy theories, which were the most numerous in this period, focused on the external actors all of which were deemed to be plotting to dismember Yugoslavia so that they can destroy Serbian people: Vatican aiming to diminish or terminate Serbian Orthodox Church by forcibly converting Serbs to Catholicism; the Masonic Order, Jewish lobby and US corporations focusing on monopolising new markets by destroying Serbian and Yugoslav economy; united Germany under chancellor Kohl and foreign minister Genscher favouring Slovenia and Croatia and aspiring to colonise Serbs in the new German Viertes Reich; US politicians such as Bush senior and later Clinton aiming to create the New World Order at the expense of Russia and Serbia; and the Muslim powers such as Turkey and Saudi Arabia plotting to divide and enslave Serbian people by establishing the ‘Green corridor’ between Bosnia, Sandžak in Serbia, Kosovo and Albania to Turkey. In all these narratives Serbian people were depicted as the ultimate victim facing greater and unscrupulous enemies and having to fight and win against all odds. The Croatian conspiracy theories tended to focus on communism and Yugoslavia as something that was imposed on Croats against their will to advance the establishment of the Greater Serbia on the Croat territories. In some of these narratives the US, UK and the Jewish-Masonic-Serb lobby have been blamed for the creation and preservation of the Yugoslav state. In other conspiracies the Serbs and the Serbian Orthodox Church were identified as continuously plotting throughout history to annihilate or convert Croats and destroy the Catholic faith in Croatia. Some narratives would also identify Jewish Bolshevik plot as driving the communist takeover of Croatia and resisting the Croatian independence. Other conspiracies invoked the global Muslim plots to remove Croats from Bosnian and Herzegovina and establish a Muslim caliphate in Europe.

Although these conspiracy theories were circulating long before the break-up of Yugoslavia it is only in the few years before the collapse of the state that they became a dominant interpretative framework shared by many citizens. The political and cultural elites played a central role in opening space for the proliferation of these conspiratorial narratives. Once these discourses attained a central place in the mass media and other outlets of the state propaganda they contributed to the outbreak of violence and justification of war aims. During the wars of 1991-1995 in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina the conspiracy theories were the key ingredient of the official state propaganda. Despite the clear diversity in the content of these narratives they all articulated and promulgated the idea that other nations have always tried to destroy us, and that we must fight them to survive. This message was firmly embedded in the historical narratives of victimhood and bravery. In Serbian conspiracies the Serbs have always been victorious in wars but were subsequently betrayed by others. The nationalist writers articulated popular phrases such as that the Serbs were ‘the remnants of the slaughtered people’ or that ‘Serbs always win wars but loose in the peacetime’. In the Croatian conspiratorial narratives Croats have always suffered throughout history for their freedom and the perfidious actions of other nations led to their enslavement. Many such narratives have been underpinned by the mystical notions propagated by nationalist leaders such as that Croatian national consciousness is characterised by ‘thousand years of unbroken continuity’ and that all Croats should follow the motto – ‘Always and everything for Croatia, and our only and eternal Croatia – not for anything’. The conspiratorial logic that underpinned these visions of the past and present would regularly depict history as an eternal zero sum game where the neighbouring nations and their allies have always plotted against our nation and despite their superior strength and inhuman wickedness our nation has always prevailed. These conflicting narratives legitimised the outbreak of war, mobilised individuals to fight and have also later been used to justify over 120,000 deaths and close to 5 million displaced people. The nationalist conspiracy theories played an important role in the violent collapse of Yugoslavia.

The Conspiracy Theories in the USA and UK

In the last few years one can witness a similar proliferation of conspiratorial discourses in many parts of the world. Several large-scale surveys have confirmed that the conspiracy theories have entered the mainstream and have become highly popular across the globe. Some of these narratives challenge the scientific explanations of various phenomena with the anti-vaxxer conspiracies blaming ‘Big Farma’, Bill Gates or scientific lobby for the covid 19 outbreak and vaccination programmes, while anti-technology conspirators link the global spread of the pandemic to the 5G network and the use of mobile phones. Other conspiracies have focused on the business corporations, environmental interests, and state power (i.e. Chemtrails, FEMA camps, RFID chips etc.). However, several conspiracies that have gained influence in the wake or Brexit and Donald Trump’s election in the US have strong nationalist overtones. The surveys indicate clearly that Brexit and Trump supporters are much more likely to believe in conspiracy theories and many of such conspiracies are nationalist. Hence YouGov poll shows that close to 50% of people who voted for Trump and Brexit believe that the government is ‘hiding the truth’ about immigration and they also express strong support for statements such as ‘Muslim immigration to this country is part of a bigger plan to make Muslims a majority’ and ‘Regardless of who is officially in charge of governments and other organisations, there is a single group of people who secretly control events and rule the world together’ (de Waal 2018). The supporters of Brexit have often depicted the EU as an imperialist plot to conquer and deprive the UK of its sovereignty and in this process dilute its ethnic structure while many Trump supporters subscribe to several nationalist conspiracies including the ideas of White genocide, Deep State, the Plan de Aztlan, North American Union project and variety of plots involving George Soros. The White genocide conspiracy blames Jews and liberals for promoting miscegenation, racial integration, abortion, and mass scale non-white immigration in order to destroy US as majority white nation. The North American Union and the Plan de Aztlan are conspiracy theories that invoke plots to surrender American sovereignty to foreign leaders by merging US with Canada and Mexico in the former case or to allow Mexico to conquer the seven southwestern US states in the latter case. The highly popular Deep State conspiracy refers to the idea that US political system is run by hidden and nonelected rulers who obstruct the legitimate government and use cronyism and collusion to keep power. The billionaire financier Soros has been linked to many different conspiracies including the Deep State, White Genocide and the North American Union and has also been identified as the main funder of the non-white immigration to the US. The common thread in all these conspiracy theories is ethnic nationalism and the notion of our (white majority) nation is in danger.

Just as in the Yugoslav case these conspiracy theories operate with a Manichean logic where national and racial groups are inherently at war with each other and only one group can prevail. The conspiracists interpret history through the prism of continuous plots where the Other has always threatened the very existence of our (ethnic) nation and despite their power and influence our nation will fight and win. Although these discourses have been in circulation for years the recent political developments including Trump’s election and Brexit have catapulted them into the mainstream. Similarly, to the Yugoslav experience the conspiratorial narratives have recently become prominent and highly visible in the public and private realms and the most influential mass media together with ever present social media have opened the space for conspiratorial thinking. The large sections of the population have embraced these interpretations and have occasionally acted on these ideas by using violence against the immigrants, or ethnic and religious minorities. The members of police, military, and other security apparatuses as well as the armed militias and vigilante groups have all relied on the nationalist conspiracy theories to legitimise the use of violence and to mobilise others for violent action.

Nationalisms and Conspiracy Theories

The nationalist conspiracies are not the only conspiracies that have proliferated in the recent years. There are conspiracy theories that focus on almost every aspect of human life: from politics, economy, industry, science, technology to sport and entertainment. However nationalist conspiracies are more potent, more durable and have a wider appeal because they draw upon the idioms that are already well entrenched in everyday life. While the ideas that 5G network causes covid 19, that FEMA is building concentration camps or that Chemtrails are real can all be easily refuted with the wealth of scientific evidence this is much more difficult for nationalist conspiracies. Most nationalist conspiracies are built upon well-established narratives of superiority, victimhood, and sacrifice that constitute the official interpretations of nation’s past in the states throughout the globe. Rather than challenging these narratives the nationalist conspiracies often just radicalise already existing nationalist mythologies. For example, the Brexit and Aztlan conspiracies draw on the already established popular views that national sovereignty is sacred and is something that must be defended. In this understanding the nation-states are the only legitimate form of territorial organisation in the world and any attempt to question the existing (inter) national order is considered to be a threat. The nationalist conspiracies build on this conventional and deeply embedded view to radicalise its message: the threat is not abstract but is located in the specific group of plotters – the imperialist Eurocrats, the Mexican immigrants, George Soros, the globalist elite and so on.

Since nationalism is the dominant operative ideology of modernity the discourses that rely on the nation-centric tropes have greater popular appeal and as such cannot easily be rebutted. Unlike many other conspiracies which have no institutional recognition nationalist conspiracies survive and flourish precisely because they work with something that is deeply grounded in the modern world – the nation-centric understanding of social reality (Malešević 2019). We are now all born, work, live and die in the polities that justify their existence through the idea that the nationhood is the ultimate form of collective solidarity and political legitimacy – nation-states. Our educational systems, mass media and the public sphere reproduce daily the nation-centred visions of the world. From our childhoods to our mature years we are constantly exposed to the nationalist mythologies of the past, present, and future where our nations are depicted as unique and exceptional. The nationalist narratives portray their nations as transhistorical entities that have always existed and that will never die: our nations have glorious history, long tradition of civility, morality, heroism, and sacrifice. Unlike our neighbours we have always upheld high moral standards and have suffered for that. These nationalist tropes are not only created and disseminated in the institutions of nation-state, they are also reproduced in civil society and the intimate sphere of close friendships and kinship networks. Hence in times of deep social crises nationalist conspiracies attract a wide appeal precisely because they tap into something that is already there. They only reshape the existing nationalist myths and practices into something more radical and more exclusionary. They feed off existing and established nation-centric discourses by clearly identifying the acute threats and concrete culprits who plot to destroy our nation. The fears and uncertainties generated by the deep political polarisation can intensify nationalist narratives and create conditions for conspiracy theorists to tap into the existing popular cognitions. The individuals who were brought up with the nation-centric mythologies are more likely to be receptive to the nationalist conspiracies. When one is socialised into believing that all Serbs continuously suffered under the five hundred years of ‘Turkish yoke’ or that heroic Brits imbued with the ‘Spirit of Blitz’ have singlehandedly defeated Nazi Germany she is more receptive to accepting the conspiratorial notions of foreign plots against our nation.

All conspiracy theories thrive in times of crises, social polarisations, and power vacuums. They offer simplified cognitive maps for what seems to be incomprehensible and scary world. They provide a sense of control and certainty in deeply uncertain times. However not all conspiracies are the same. Unlike most other conspiratorial discourses nationalist conspiracies are more powerful, more durable, and as such also more dangerous. Their strength resides in their parasitic quality as they feed off already existing nation-centric narratives that are deeply grounded in the institutions, everyday practices and believes of individuals that live in nation-states. The nationalist narratives and conspiracy theories share one important common feature: they cannot be built on truth. Their purpose is not to generate objective knowledge but to enhance social cohesion. As such they are both resistant to scientific analysis and factual evidence. Nobody wants to hear that their nation is inferior, has shameful past, mediocre qualities, or cowardly ancestors. The very existence of nationhood is premised on the sense of unique qualities that signify some kind of superiority. The same applies to the conspiracy theories. They are impervious to reason as they offer individuals a sense of security, direction, and a feeling of supremacy through the nonpareil access to the information that others do not have. The nationalist conspiracies just bring the nation-centric understanding of reality to its logical conclusion. In times of deep social turmoil ordinary nation-centric idioms easily transform into popular nationalist conspiracies.

References:

de Waal, J.R. (2018) Brexit and Trump voters are more likely to believe in conspiracy theories. International YouGov Poll-Cambridge Centre.

Hart, J., & Graether, M. (2018). Something’s going on here: Psychological predictors of belief in conspiracy theories. Journal of Individual Differences, 39(4), 229–237

Malešević, S. (2019) Grounded Nationalisms. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pingback: Two short papers on nationalism « Sinisa Malesevic

Hi Siniša,

Thanks for this lucid piece, which comes, I imagine , out of a commitment to try to mitigate the inhumane impulses in all of us.

I agree with all of the points you make, but one.

As you say, current nationalist conspiracy theories feed off pervasive and deeply rooted tropes. I think the “the intimate sphere of close friendships and kinship networks” is almost always underestimated as a “rhizomatic” conduit for forms of nationalist inspired hatred of the other, who ever that happens to be.

Connected to that and equally underestimated is the resurgence, in times of “crisis”, of patriarchal and masculinist tropes which try to inculcate aggressive group mentalities and irrational hatreds into the minds of young men, almost always the backbone of any nationalist resurgence. The so called “troubles” in northern Ireland attest to that, as does the Serbian and Croatian experience, of course.

I think the complex relation between Globalisation and the existence and persistence of nation-states is often reduced to a simplistic dialectic in which technological/economic acceleration and corporate expansion is opposed to and will eventually overcome what are often dismissed as primitivist and instinctual nationalistic impulses. This simplification is especially true for the well entrenched liberal elites of “old” Europe and America, who are, of course, highly embarrassed by Trump and his supporters, or by the excesses of the extreme Brexiteers.

Which brings me to the one reservation I have about your piece.

“ The nationalist narratives and conspiracy theories share one important common feature: they cannot be built on truth. Their purpose is not to generate objective knowledge but to enhance social cohesion. As such they are both resistant to scientific analysis and factual evidence…they are impervious to reason as they offer individuals a sense of security, direction, and a feeling of supremacy through the non-partial access to the information that others do not have.”

Well, I think there are too many unexamined presuppositions here, perhaps?

The way “objective knowledge” is actually generated, that is as an outcome of a complex of modes practices and structures, inclusive of but not determined by, logical or rationalist methodologies, is well established by science studies. The rationalism which liberal ideologues continually trumpet as the only civilised alternative to forms of conceptual primitivism is just that, an ideology.

That the practice of science is enabled by non-scientific interests, as much driven by irrational impulses and ideological tropes, is undeniable.

The purveyors of reason are almost always “impervious to reason”. The purveyors of reason, too, are prone to cultivate “a sense of security, direction, and a feeling of supremacy through the non-partial access to the information that others do not have.”

Indeed, if one contemplates the relation between the science academy and corporate or nation state interests (they are often the same thing) one has to conclude that the “non-partial access to the information that others do not have” is an example of a real conspiracy of the powerful over the powerless, of the “knowledge producers” over the (so-called) ignorant and excluded other.

Sadly, the world is more complex than any rationalist scientism would have us believe and precisely because rationalism and scientism (partially) enable it.

And even if there are forms of “objective” knowledge(s), they are humanly produced and cannot, therefore, have any ethical, moral or political jurisdiction over the human as such.

LikeLike

Dear Patrick

Thank you for your insightful and engaging comments. Saying that nationalism is impervious to truth does not imply that other ideologies are somehow immune to this. All ideologies, including liberalism, prioritise social cohesion over truth and in this sense are resistant to factual evidence. Glorifying reason and rationality (as in some forms of liberalism) is even a better strategy to conceal one’s ideological biases (This is what Pinker and others like him do). I have written about this extensively in my first book – ‘ideology, Legitimacy and the New State’ (2002) and also discuss it in my 2017 book (The Rise of Organised Brutality). My focus in this short piece is on nationalism but I have explored other ideologies as well. In my work I have been critical of both rationalism and relativism. I see them both as deeply problematic epistemological strategies. However, I would not conflate rationalism with the facts and evidence. I am well aware that, and have written extensively about this, science should not be reduced to its dominant positivist incarnation. Nevertheless, I am also critical of relativist positions (i.e. Feyerabend etc) as they are logically and morally unsustainable.

All the best

Sinisa

LikeLike

Thanks for your response. I look forward to following up by reading more of your work. I should have said cannot have any transcendent or absolute jurisdiction over the human, of course. As for relativism I agree, even if, as far as irrationality and brutality goes, relativism is far preferable to dogmatism. And there are alternatives, of course, to both relativism and dogmatism. Perhaps your work will offer some such alternative?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Nightcap | Notes On Liberty

Pingback: The geopolitical unmoored: from exemplarity to deprovincialization | The Disorder Of Things