This is another in my “Short Lives Remembered” series. It focuses on often-forgotten children in family trees who died all too young. The ones who never had chance to marry, have children and descendants to cherish their memory. The ones who, but for family history researchers, would be forever forgotten.

This post is about Sarah Clough. Sadly the most remarkable thing I know about her life is her death.

Sarah was the fourth child of my 3x great grandparents William and Mary Clough (née Burnett). She was born on 22 February 1833 in Adwalton Yorkshire and baptised in the parish church of St Peter’s, Birstall on 2 June 1833.

Historically, Adwalton is probably best known for its part in the English Civil War: The scene of the Battle of Adwalton Moor, when the Royalist forces of the Earl of Newcastle defeated the Parliamentarian forces of Sir Thomas Fairfax bringing Yorkshire under Royalist control.

Alongside it’s neighbour Drighlington, to where the Clough family moved, this was an otherwise historically unremarkable village, following the normal industrial revolution growth and development patterns of other West Riding villages in the 19th century.

By the time of Sarah’s birth, textile manufacture was supplanting farming and mining as principal occupations in Adwalton and Drighlington. William, her father, worked as a clothier, following the traditional occupations of the area. This was before fate stepped in and his working life took a totally different path. But that’s for another time.

Sarah only features in one census, that of 1841. She is shown living in Drighlington with her parents and three older siblings. The next record I have is her death certificate. Which brings me to a period in time when Drighlington hit the news for entirely unwelcome reasons.

Sarah died there on 10 August 1849, age 16. No occupation given, so I do not know if she followed her elder sister into a worsted spinning job in one of the area’s relatively new mills. She’s described merely as the daughter of William Clough. He registered her death the following day.

The certificate reveals she suffered one of those truly awful, and all too common, deaths of our ancestors. It indicates she died after suffering for 11 hours from “malignant cholera”.

So once more I venture into the depressing medical world family history researchers frequently inhabit. This time learning about cholera.Malignant cholera was one of the names given to Asiatic cholera. This was distinct from English cholera. Adverts in 1849 stated that English cholera, which all persons more or less suffered from in summer months, was characterised by “violent looseness of the bowels, attended with sickness, and in extreme cases violent cramps”. In other words dysentery and food poisoning, more commonly known as gastroenteritis today. If left untreated it could result in Asiatic cholera, or so some quack newspaper adverts claimed.

In fact Asiatic cholera was a different entity. Originating in India, it first reached the shores of Great Britain in the autumn of 1831, after its relentless march across Europe. It’s first victim was in Sunderland. The epidemic dissipated the following Autumn, but not before claiming the souls of some 32,000 people, roughly a 50 per cent death rate of those afflicted. In these pre-civil registration days this is only a rough estimate, with ranges fluctuating between 20,000 to 50,000+[1]

L0008118 A dead victim of cholera at Sunderland in 1832. Coloured lit Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images images@wellcome.ac.uk http://wellcomeimages.org A dead victim of cholera at Sunderland in 1832 by IWG. Coloured Lithograph Circa 1832 Published: – Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

V0010485 A young Viennese woman, aged 23, depicted before and after Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images images@wellcome.ac.uk http://wellcomeimages.org A young Viennesen woman, aged 23, depicted before and after contracting cholera. Coloured stipple engraving. Published: – Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Official advice, as well as druggists adverts, featured in the press of the day. All equally ineffective.

Fundamental to the grip the frightening disease had on the country was the lack of understanding of its causes and transmission. The prevalent theory was that the disease was caused and spread by smelly, contaminated air, otherwise known as miasma. Getting rid of foul smells, including improved sanitation, would combat the deadly menace. Attempts were made to fumigate buildings in affected communities by burning sulphur or tar. Drinking brandy or eating copious quantities of garlic were also widely believed to be a preventative measures.

L0003001 A court for King Cholera Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images images@wellcome.ac.uk http://wellcomeimages.org ‘A court for King Cholera’ is hardly an exaggeration of many dwelling places of the poor in London. 19th century Punch Published: 1852 Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

In terms of fatalities this second outbreak of the disease proved to be the most serious of 19th century epidemics to hit Britain. Estimates vary between 53,000 and 62,000 lives lost[2], including that of Sarah Clough.

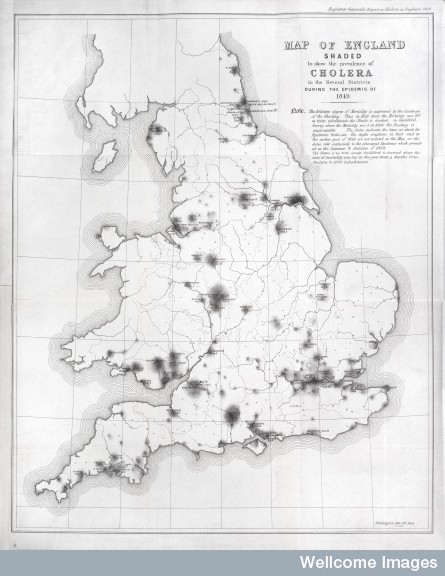

L0039174 Map of England showing prevalence of cholera, 1849 Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images images@wellcome.ac.uk http://wellcomeimages.org Map of England shaded to show the prevalence of cholera in the several districts during the epidemic of 1849. The relative degree of mortality is expressed in the darkness of the shading. The dates indicate the time at which the epidemic broke out. Printed Reproduction 1852 Report on the mortality of cholera in England, 1848-49. Great Britain. General Register Office. Published: 1852. Copyrighted work available under Creative Commons Attribution only licence CC BY 4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

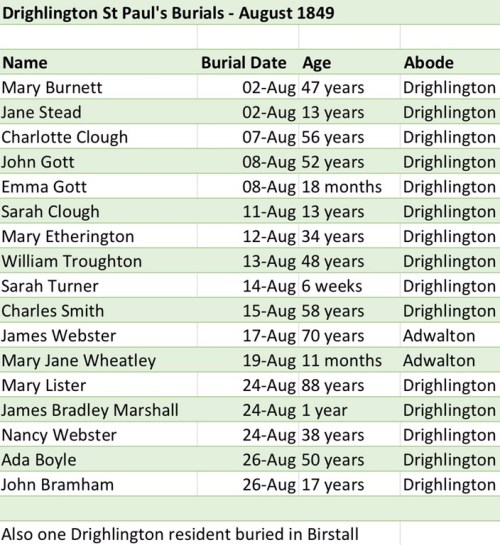

Drighlington was particularly hard hit. Looking at the Drighlington St Paul’s burial register Sarah was just one of many of the village’s inhabitants to die in the summer of 1849.

A look at the a parish register shows 17 burials in August 1849. Of these 15 were Drighlington inhabitants, two from Adwalton. Sarah’s burial took place on 11 August 1849. Compare this with three June burials; four in July; one in September; four in October. Looking at the month of August in the years sandwiching 1849, August 1848 had four burials; whilst August 1850 shows only one. So a dramatic spike that cholera-affected month of August 1849.

The terror of the inhabitants felt is unimaginable: An illness with an incorrectly vague cause and no known cure sweeping their hometown; neighbours, friends and families being suddenly struck down; a succession of funerals held in the local church; many more suffering the distressing and debilitating effects of the illness.

Newspapers, filled daily with cholera returns and countrywide reports, ratcheted up anxiety levels. They even remarked on the disproportionate numbers affected in Drighlington. For example, this from the “Bradford Observer” of 16 August 1849:

“In our last number, we recorded a death from Asiatic cholera in Drighlington. Since then, five other cases have occurred, all of which proved fatal. Taking into consideration the size of the village and the population, this fearful malady is spreading more rapidly than in towns, where the population is so dense. The number of deaths from Asiatic cholera since the commencement a fortnight ago being seven, besides several others from English cholera”.

The “Leeds Intelligencer” of 18 August 1849 put the number of deaths at 11 and described clean-up measures to tackle the outbreak.

Put into context the 1851 population of Drighlington township was 2,740. So 11 cholera-related deaths in such a short space of time, not to mention those infected and recovering, and it’s easy to see how ravages of the illness would affect a significant proportion of the village one way or another.Two further waves of cholera swept Britain but with decreasing death tolls – the 1853-54 outbreak claimed 20,000 souls[3]. Following this outbreak John Snow was able to prove his theory about the bacterial nature of the disease, when he isolated the source of the 1854 Soho outbreak to a contaminated Broad Street water pump.

Although full acceptance was slow, it was an important step in paving the way to laying to rest the bad air/miasma theory. This, ironically combined with the Public Health Acts and Sanitary Act resulting from the work of Chadwick, meant the disease was increasingly more effectively prevented and the 1865-66 epidemic accounted for a mere 10,000 – 14,000 deaths, depending on statistical sources.[4].

It wasn’t until 1883 that a German doctor, Robert Koch, isolated the cholera bacillus. And over 30 years more years elapsed before a vaccination became generally available in 1914.

So the short life of Sarah Clough is significant for the disease which cut it short. Just one of many thousands of people mowed down in Britain alone in what were the worldwide 19th century cholera pandemics. As a result of my research into Sarah’s death, the disease for me is now more than a name.

Others who feature in this series of “Short Lives Remembered” posts are:

- Thomas Gavan – a census in-betweener

- Oliver Rhodes – 1910 Morley car accident

- Margaret Hill – my grandad’s forgotten sister

Footnotes:

- [1] 32,000 in Britain according to www.parliament.uk at http://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/towncountry/towns/tyne-and-wear-case-study/introduction/cholera-in-sunderland/

- [2] 53,293 according to the “Report on the 1866 Cholera Epidemic in England” (so excluding Scotland)

- [3] 20,097 according to the “Report on the 1866 Cholera Epidemic in England” (so excluding Scotland)

- [4] 14,387 according to the “Report on the 1866 Cholera Epidemic in England” (so excluding Scotland)

Sources:

- Cholera comes to Britain – October 1831: http://www.historyhome.co.uk/peel/p-health/cholera3.htm

- Cholera in Sunderland: http://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/towncountry/towns/tyne-and-wear-case-study/introduction/cholera-in-sunderland/

- GRO Death Certificate: Sarah Clough

- “How our Ancestors Died” – Simon Wills

- Histpop: http://www.histpop.org

- John Snow, William Farr and the 1849 outbreak

of cholera that affected London: a reworking of the data highlights the importance of the water supply: http://www.ph.ucla.edu/EPI/snow/publichealth118_387_394_2004.pdf - Newspapers – as indicated in text

- Parish Registers: St Peter’s, Birstall and St Paul’s, Drighlington

- Report on the Cholera Epidemic of 1866 in England: http://wellcomelibrary.org/item/b24976854

- Sutherland, Snow and water: the transmission of cholera in the nineteenth century: http://ije.oxfordjournals.org/content/31/5/908.long

- The Cholera Epidemics of 1832 and 1849: https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/manuscriptsandspecialcollections/learning/healthhousing/theme3/epidemics.aspx

- Wellcome Images: https://wellcomeimages.org/

GRO Picture Credit:

Extract from GRO death register entry for Sarah Clough: Image © Crown Copyright and posted in compliance with General Register Office copyright guidance.

Wow, so interesting