Immersing myself in the lives of my ancestors inevitably means dealing with their deaths. Lots of them. Because I invest so much time in my research, that connection with my ancestors goes way beyond the simple bloodline link. Learning about their lives and struggles, I develop an emotional attachment. Discovering their deaths, which were occasionally under traumatic circumstances, can stop me in my tracks. And whilst not quite moving me to tears it can bring a lump to my throat. I’m not sure if this is a common feeling amongst other family history researchers.

The deaths of children can be particularly difficult. They never had a chance to make a mark, achieve their potential, fulfil their parent’s hopes and dreams, marry and have families of their own. But for family history research, many would be forgotten for ever. One of my first blog posts, A Census In-Betweener, was one such example. It remembered the all too fleeting existence of Thomas Gavan, my great grandmother Bridget Gavan’s eldest child. Towards the end of the year another post focused on the tragic accident in which Oliver Rhodes died. He was the son of my great grandparents Jonathan Rhodes and Edith Aveyard.

Victorian Headstone for a Child – Photo Jane Roberts

In this post, as well as describing what little is known of her short life, I will try to give a flavour of the times in which she lived.

In 1897 Bridget Gavan married coal miner John Herbert (Jack) Hill. Jack was a widower, Bridget an unmarried mother of two girls, though it is possible Jack was the father of the younger of the two, Agnes.

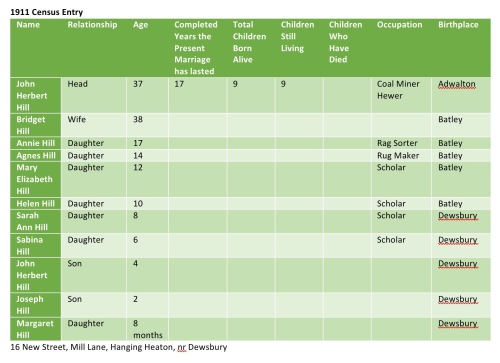

Jack and Bridget went on to have seven further children. Margaret, their final child, was born on 29 August 1910 in the family’s home at 16 New Street, Hanging Heaton. The family now totalled nine children ranging from newly-born Margaret to eldest Annie, who celebrated her 17th birthday the day before Margaret’s arrival.

The 1911 census shows the complete family unit. It is notable for Jack and Bridget’s judicious tinkering with names and dates. Interestingly they claimed to have been married for 17 years, which conveniently corresponded with the age of Bridget’s eldest daughter Annie who is listed as “Annie Hill”, not Gavan. Daughter Agnes, also born outside of wedlock, is similarly listed as Hill and not Gavan. All nine children are claimed as “children born alive to present marriage”. There is also the usual flexibility around adult ages to minimise the gap between Jack and Bridget’s ages (she was born in 1869).

In terms of events during Margaret’s short life, 22 June 1911 marked the coronation of the new King, George V, and his wife Queen Mary. A cause for celebration with parades, parties, decorations and a bonfire to mark the occasion. And in December that year the Liberal Government introduced a National Insurance Act. It meant for that workers would have cover against sickness and unemployment. So there was perhaps some optimism as the things seemed to be on the up for families like Jack and Bridget’s. But this may have been tempered as a result of industrial action the following year, and its affects on family income.

In terms of events during Margaret’s short life, 22 June 1911 marked the coronation of the new King, George V, and his wife Queen Mary. A cause for celebration with parades, parties, decorations and a bonfire to mark the occasion. And in December that year the Liberal Government introduced a National Insurance Act. It meant for that workers would have cover against sickness and unemployment. So there was perhaps some optimism as the things seemed to be on the up for families like Jack and Bridget’s. But this may have been tempered as a result of industrial action the following year, and its affects on family income.

Miners were notoriously militant with frequent strikes. The records of the Yorkshire Miners Association (YMA) show in the latter part of the 19th century and early into the 20th Soothill Wood, the pit where Jack worked, was one of the more non-militant and politically moderate pits. Nevertheless, although being characterised in district ballot votes as non-militant it was conversely, even then, regarded as particularly “strike prone”.

Just a glimpse through newspapers show for instance strikes were threatened in 1892 over amongst other things distribution of corves. A short strike took place in 1894 over reduction of wages. Outside this period, a lengthy strike took place in 1906 affecting not just Soothill, but wider throughout Yorkshire. And in 1912 there was a national strike, lasting five weeks, the objective being a national minimum wage.

The national strike began in February, Britain in the grip of yet another severe winter with temperatures plummeting and thousands dying of hypothermia. Heavy snow fall had affected Yorkshire at the end of January. A strike was the last thing Britain needed at this particular time. As a result of the action more than a million people were out of work.

Although the outcome was not as profitable as the miners wanted, hewers in the Batley area, such as Jack, were guaranteed a minimum daily wage of 6s 8d, subject to clauses around for example age and attendance, although some employers did try to flout this.

Then another 1912 Soothill strike in early July resulted in 72 men being summoned to appear in court that month – just a small fraction of the hundreds involved.

A newspaper report in 1918 stated the wages of a Soothill Wood Colliery averaged of £2 13s a week. But this needs to be seen in context of the economy at the time. Since the beginning of the war to 1916 there was an estimated 45 per cent reduction in the purchasing power of foodstuffs. Soothill Wood is more accurately described as a low to average pit in terms of wage level during the period 1894-1918.

So although the Hill family were not in the poorest category, life would still be a struggle full of difficult spending choices to make. Balancing how much to spend on rent against food and other essentials such as coal (although this would be cheaper than the norm given Jack’s job), lamp oil, gas, wood, candles, matches, soda and soap (a particular high usage item for a mining family), blacking and transport costs. And if you went for cheaper rents, these houses would be smaller, damper and darker resulting in higher expenditure on fuel and lighting, not to mention being more detrimental healthwise.

The family would weigh the affordability of burial insurance against the risks of not having it. As we saw in the story of Thomas Gavan, Bridget was minded to take out insurance, but was this still the case with a much larger family?

Then there was clothing and boots. Could they afford to put aside weekly in a clothing or boot club, or were they faced with the hit of paying it all upfront as and when needed? The school log book for St Mary’s, the school the Hill family went to, has accounts of children not being sent to school for lack of boots during this period.

And then there would be budgeting for emergencies such as medicine and doctor’s bills.

As for food, for the working class it was bland and monotonous, the emphasis being on staving off hunger rather than nutrition. Men, the breadwinners, had the most. They needed to be fit and strong to go out to work, especially for a manual job such as Jack’s. The principal article of diet in this period was bread which was cheap and convenient. It was followed some way behind by potatoes, meat and fish. Meat was principally bought for the men, with the main expenditure being on Sunday dinner when the entire household would be at home. Cold cuts from Sunday would be eaten on Monday, eked out longer if possible. When potatoes did not feature, the replacement would be suet pudding with golden syrup. There would be the occasional egg, and tiny amounts of tea, dripping, butter, jam, sugar and greens.

Milk, although crucial for children in particular, was costly. There were also issues of storage to consider in these years before refrigeration. A pint of milk a day for an infant or child would equate to around 1s 2d a week when the food for a whole family may have to be supplied out of 9s a week after all other household expenses were taken into account. As a result women nursed their babies as long as possible, often until they were about one year old. After that often the only milk children got was tinned evaporated milk, this despite it not being recommended for infants. This tinned product was used in tea, and sometimes also used as a spread on bread. Where boiled milk was given to babies and infants it was often thickened with bread and biscuits in an attempt to bulk it out. In 1916 the local Coroner censured such a practice in the inquest of the baby son of a fellow Batley St Mary’s parishioner. But the reason why infants did not get milk was the same reason they lacked good housing and clothing – it came down to cost and family finances. In short the diet where there were several children in a family, such as the Hills, would be chosen for its cheapness and for its filling, stodgy qualities.

All of these considerations may have played a part to some extent in Margaret’s death.

On a national scale one event dominated 1912. British confidence was shaken in the spring when news reached home of the unthinkable, the sinking of the “Titanic” on 15 April, with the loss of more than 1,500 lives. Headlines screamed out from billboards and newspapers – day upon day of grim news. Deaths included those of bandleader and Dewsbury resident Wallace Hartley, with tales of how the band played on adding to the whole pathos surrounding the event.

There were perhaps some particular highlights to the Hill’s year though. On 10 July 1912 following much preparation and accompanied by great excitement King George V and Queen Mary visited Batley. A three minute ceremony in the market square was attended by around 4,000 school children hoping to catch a glimpse of their monarch. However, it ended in disappointed children and much indignation on the part of parents and teachers when many failed to see the Royal couple, such were the crowds and the swiftness of the event. Margaret was too young, but some of her siblings may have taken part and returned home dispondant.

It is also doubtful whether the event took Jack’s mind off the Soothill Wood Colliery strike which culminated in those July court cases.

On a more personal family level one event dominated the year – the marriage of Bridget’s daughter Annie to Lawrence Carney on 30 November 1912.

So things ticked over until 4 August 1914, when a life-changing announcement was made which would affect many families nationwide: Britain declared war on Germany. There now followed a period of intense hardship and sorrow for many families including the Hills, now living at 2 Yard, 2 Victoria Street in the town’s Carlinghow area. But that was still to come.

With the war in its infancy and family members, such as Lawrence, now serving in the military, tragedy closer to home struck the family. On 9 October Margaret, died age four, as a result of tuberculous (TB) meningitis. She was one of only nine people in Batley Borough to die of this illness in that year.

TB meningitis typically affected children under ten years of age. It was especially associated with improper feeding, malnutrition, poor hygiene or childhood illnesses such as measles and whooping cough. Caused by tuberculosis bacteria invading the membranes and fluid surrounding the brain and spinal cord, it usually began with vague, non-specific symptoms such as fatigue, listlessness, loss of appetite and headache. The afflicted child became peevish and irritable. Vomiting and constipation followed along with a dislike of lights and sound. As the headache intensified the child would scream with a peculiar cry and display classic neck stiffness. As the disease progressed seizures occurred, the child lapsed into a coma and eventually died. Horrifically Margaret suffered these symptoms and decline over a period of three weeks.

Apart from the tragedy, such an event was crippling financially to already hard pressed families. A child’s funeral alone could cost upwards of £2, including a death certificate, funeral costs, flowers, gravediggers, hearse attendants, a woman to lay the body out, and a black tie for the father. Most families took out burial insurance. This cost on average each week 1d per child, 2d for a mother and 3d for a father, though some overcautious women paid more. So for the Hill family, with their flock of children, this would amount to a weekly sum of just over 1s. But even with insurance a burial plot may not have been affordable.

Batley Cemetery – Photo Jane Roberts

Margaret was buried on 12 October in a common grave in Batley cemetery, echoing the fate of her eldest half-brother Thomas Gavan.

Sources:

- Batley News

- Batley Reporter & Guardian

- Batley Cemetery Burial Records

- Batley Medical Officer of Health Reports

- GRO certificates – Birth and Death certificates for Margaret Hill

- “The History of the Yorkshire Miners 1881-1918” – Carolyn Baylies

- “The History of Batley 1800-1974” – Malcolm Haigh

- “Round About A Pound A Week” – Maud Pember Reeves

- St Mary of the Angels School Log Book

- FindMyPast – 1911 Census