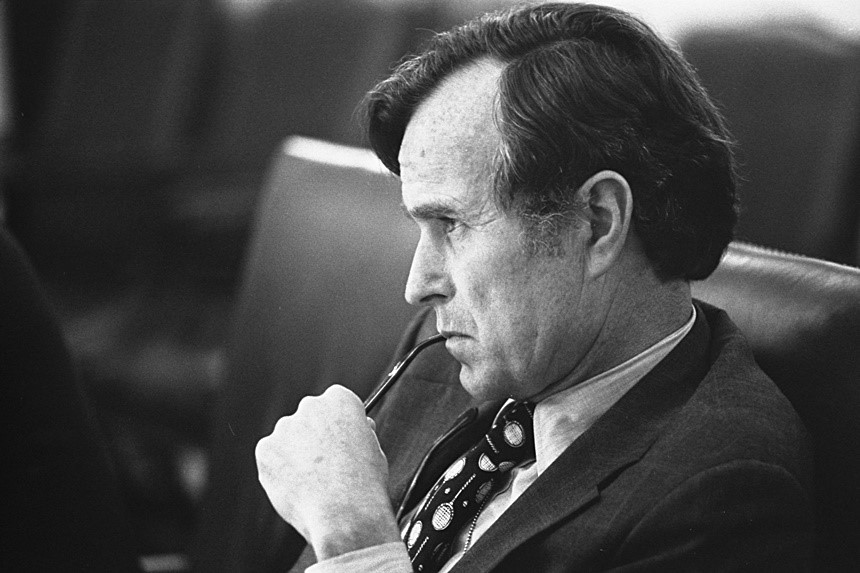

First and foremost, the death of George Herbert Walker Bush is a human loss, the passing of an elderly man who lived a long and good life and will be mourned but also remembered and celebrated by his family, loved ones, and communities small and large. As with any death, those stages of grief, mourning, memory, and celebration should be respected and honored, in public eulogies as in every other way.

But former presidents are more than just private individuals, of course. They are among the most recognizable and prominent public faces of the nation, representatives of our history and identity. Remembering the histories to which their lives connect isn’t politicizing their deaths—it’s understanding what in us they help us see and analyze. And in Bush’s case, his public career and presidency illustrate some of the best and some of the worst of 20th century America, through a number of key themes.

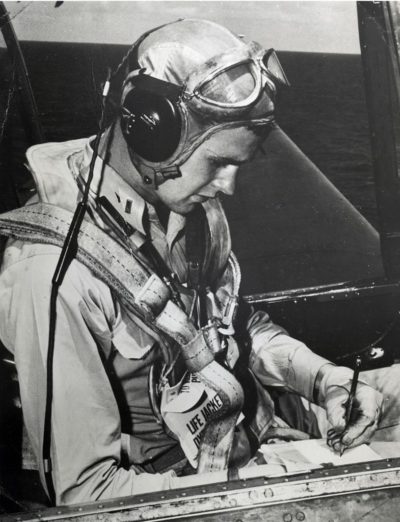

Take war, for example. Bush’s World War II service embodies “Greatest Generation” images and ideals. As the son of a wealthy New England family, Bush could certainly have avoided service if he chose; but instead, in June 1942, immediately after graduating from the prestigious Phillips Academy and turning 18, Bush postponed his college career to enlist in the U.S. Navy. He was a naval aviator before he turned 19, making him one of the youngest aviators in the service. He served impressively in the war’s Pacific Theater throughout the conflict, including his famous experience surviving a fighter crash and subsequently helping rescue other downed aviators.

Yet as president, Bush was connected to an example of the worst of wartime excesses. The first Gulf War was a controversial one in any case, driven by a combination of factors including international law (in response to Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait) and American energy interests. Moreover, Bush’s Ambassador to Iraq, April Glaspie, had tacitly supported Hussein’s planned invasion. And during the war, U.S. forces committed at least one serious violation of international law in their own right, bombing a Baghdad air raid shelter that they knew to be a civil facility and killing at least 400 Iraqi civilians. Perhaps such excesses are an inevitable part of war, but that makes them an inevitable part of Bush’s wartime legacy as well. Although so too, to Bush’s credit, is his decision to end the war without pursuing Iraqi forces to the capital, greatly reducing casualties as a result.

Bush’s broader foreign policy legacies are also complicatedly mixed. Bush was president during two of the most significant culminating Cold War events, the November 1989 fall of the Berlin Wall and the December 1991 dissolution of the Soviet Union. By all accounts, Bush’s measured and pragmatic perspective and approach both contributed to these crucial changes and, perhaps most importantly, helped make sure that their democratizing effects could continue. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, for example, Bush met with Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev at a summit in Malta; some U.S. advisors believed the meeting to be premature, but Bush seemed to agree with Gorbachev that “We are just at the very beginning of our road, long road to a long-lasting, peaceful period,” and indeed the Malta conference among other steps helped produce that period.

Yet before and during his presidency Bush also took part in some of the worst of America’s 20th century foreign policy roles: as an active supporter of dictatorial regimes around the world. During his late 1970s year as CIA director, Bush helped suppress an intelligence report blaming Chile’s military dictatorship for the assassination of a Chilean dissident and an American woman working with him, leaking a false report instead. During Bush’s presidency, Zaire’s brutal military dictator Mobutu Sese Seko, a longtime ally of Bush (and of President Reagan before him), was the first African head of state to visit the White House. And even the controversial overthrow of Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega was linked to such histories, as Reagan and Bush had supported Noriega’s rise to power as part of their broader Cold War strategy of supporting Central American right-wing dictatorships to oppose communist forces in the region.

On the domestic front, Bush has frequently been linked to conversations about civility and bipartisanship in American political and civic life. Exhibit A in those narratives is the handwritten letter that Bush left in the Oval Office for his successor as president, Bill Clinton; although Clinton had just defeated Bush in an acrimonious campaign, Bush’s letter did indeed embody not only a peaceful transition of power, but also a warm and collegial attitude toward this political rival and his incoming administration. In this way, as in his self-deprecating embrace of Dana Carvey’s impersonation of him (among other arenas), Bush did represent a far different political climate than that of 2018 America.

Yet in his prior, successful 1988 campaign for the presidency, Bush relied on an attack ad that embodied instead the worst of cynical and divisive partisan politics and national narratives. The infamous Willie Horton TV ad used the image and story of a frightening African American convicted rapist to indict Democratic candidate Michael Dukakis as soft on crime, and more exactly used racist and white supremacist fears to undermine Dukakis’s lead in polls and fundamentally shift the political and social conversations about the campaign. The ad has generally been attributed to Bush’s campaign manager, Lee Atwater, who apologized for it on his death bed; but Bush was the candidate for whom it was created and whose victory it helped assure, and he is thus intimately implicated in one of the century’s most egregiously divisive and bigoted political moments.

These are some a few examples of Bush’s complex and contradictory legacy, which could also include on the one hand the civic ideal of the “Thousand Points of Light” and on the other the dark reality of Bush’s refusal to support gay Americans at the depths of the AIDS epidemic. Such contradictions are part of the story of George H.W. Bush but also of late 20th century America, and remembering them as we mourn his passing and celebrate his life helps us better understand those collective histories and their 21st century legacies.

Become a Saturday Evening Post member and enjoy unlimited access. Subscribe now