Archival Spaces 261

My 50 Years in Film Studies

Uploaded 22 January 2021

After my freshman year at Ohio University, which ended prematurely with the Ohio National Guard occupying campus in the wake of the Kent State killings, I transferred to the University of Delaware, because my parents had moved there from Germany and I was able to attend as an in-state student. I still wasn’t sure whether I would declare English or History my major, but I did have to find off-campus housing, due to lack of dormitory space. One of my three flatmates at the Colonial Gardens Apartments was Joe Johnston, who had ambitions to become a filmmaker, so the apartment began filling up with film books, which I started to peruse. Do you mean one can actually study this stuff? I was intrigued by the mixed media – images and texts – of most film books at that time, but sensed only much later that this was in fact a new field, not overcrowded with dozens of dissertations on Shakespeare or the Franco-Prussian War.

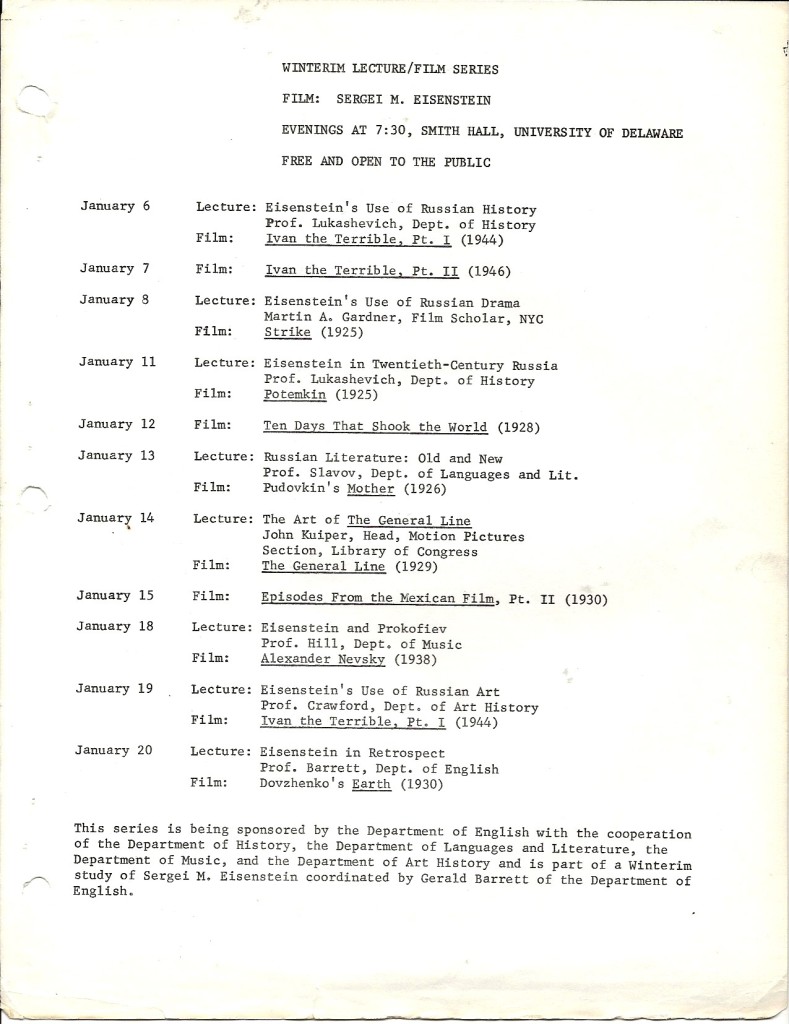

I was not a film buff but a reader, although I had started going to Ohio U’s excellent campus film programs the year before, seeing a number of Ingmar Bergman films, which perplexed me, as well as Jean-Luc Godard’s Sympathy for the Devil (1968), which infuriated me. And I did have an early epiphany about film’s power when I saw Stanley Kubrick’s 2001. A Space Odyssey (1968) in high school, which baffled and impressed me. In any case, in January 1971, the middle of my sophomore year, the University of Delaware instituted a new experimental “Winterim” program which allowed students to take a 1-3 credit, pass/no record course on a topic of interest, outside of the usual academic requirements. Joe and I discussed signing up for a lecture/film series dedicated to Sergei M. Eisenstein, then he disappeared to New York. I, of course, had no idea what I was getting myself into or that film study would morph into a fifty-year professional career.

The Eisenstein course consisted of afternoon sessions, where Gerald R. Barrett lectured and discussed the assigned readings, followed by evening lectures and screenings open to the public. We met for the first time on January 6, 1971, with a screening of Ivan the Terrible, Part I (1944), accompanied by UD Professor Stephen Lukashevich’s lecture on Eisenstein’s use of Russian History, and ended with a screening of Dovzhenko’s Earth (1930) and a lecture by Professor Barrett, summarizing the two week course. Barrett, who was teaching in the English Department as an ABD, had organized the course and was particularly interested in film studies, later becoming my first mentor.

There followed in quick succession, Ivan the Terrible, Part II (1946), Strike (1925), Potemkin (1925), Ten Days That Shook the World (1928), Pudovkin’s Mother (1926), The General Line (19239), ¡Que Viva Mexico! (1932) and Alexander Nevsky (1938). While most of the lectures were given by UD professors from the departments of history, art history, and music, Martin A. Gardner, a New York film critic, and John B. Kuiper, Head of the Motion Picture Division of the Library of Congress, presented talks on Russian drama and The General Line, respectively. John had written his dissertation on Eisenstein at the University of Iowa in 1960. Ironically, I had no memory of him when we met four years later at LOC, while I was visiting as a George Eastman Museum intern; nor could I have anticipated that he would become my boss at GEM thirteen years later.

That lack of memory was probably connected to the fact that I was indeed totally over my head. Not only were all the prints dupey 16mm copies, probably rented from Audio-Brandon, but the silents were also shown without musical accompaniment, as was the practice at the time; no restorations with full orchestral scores. Hardly a great introduction for someone who had never seen a full-length silent film. That Eisenstein’s films are intellectually challenging, goes without saying, even if you possess the critical vocabulary, which I certainly didn’t. But I was fascinated, especially Potemkin, and Mother, the latter possibly because it more closely conformed to my underdeveloped viewing experience.

The assigned readings included excerpts from Arthur Knight’s The Liveliest Art, Ivor Montague’s Film World, Dwight MacDonald’s essay on Eisenstein and Pudovkin, as well as selections from Eisenstein’s Film Form, Film Sense, and Film Essays. The readings were also difficult for a beginner, especially the Eisenstein texts. I read, but it would take several years of rereading and reviewing before I actually understood.

Another student in the Eisenstein course, George Stewart, became a life-long friend, and we both followed up by taking Jerry Barrett’s “Intro to the Art of Cinema” course in the Spring semester of that year. For that course, I wrote a final research paper on the Czech New Wave, which had been getting a lot of press in America at that time. I had been in Prague until five days before the 21 August invasion in 1968. When I went to pick up my paper at the end of the semester – a habit students no longer engage in – Barrett ask me, whether he could publish it in a book he was writing on teaching film studies. The book never appeared, but now I was hooked, deciding to make film my career. I subsequently took a number of other film courses with Barrett and started writing film reviews for the UD student paper, The Review. I admit, I liked to see my name in print and loved watching movies. I was just waiting for Jay Cocks to move on at Time, so I could take his place.

I learned so much from Barrett and even worked on a formalist film he made that seems to be lost. It has been a long journey with so many interesting twist and turns that seems like it started only yesterday. The best thing to happen of late is the amazing improvement in the restoration of silent films and the depth of available titles, bit ironic as interest in film history and aesthetics deminishes with every passing day.

LikeLike