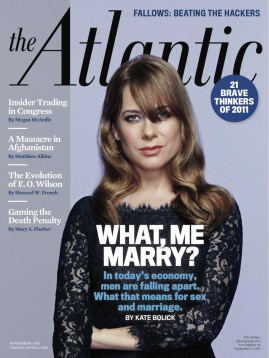

In her late 2011 Atlantic cover story “All the Single Ladies,” Kate Bolick makes the case to stop treating unmarried (and often professional, highly educated) women as anomalies or deviants—not only for the sake of feminist values, but also because increasingly, the numbers belie that notion. If you never got around to reading the piece, it remains timely.

Bolick soon signed a book deal to expand on this thesis. A few years later, Spinster: Making a Life of One’s Own is part warm, wry memoir and part painstakingly researched cultural history. Bolick is a careful technician and a caring stylist, so that despite jumping back and forth in both American history and the timeline of her life, you remain anchored to the stories of singular (if not always single) women, and to central questions about marriage, solitude, work, and value.

It reminded me of nothing so much as “Schopenhauer as Educator” from Friedrich Nietzsche’s Unfashionable Observations, usually translated Untimely Meditations.

“But wait,” you might understandably ask, “what does a warm, wry 21st century feminist journalist have in common with two grumpy 19th century German philosophers?”

Both “Schopenhauer as Educator” and Spinster are engagements with figures whom their authors never knew in person, but who nevertheless shaped their lives profoundly. Awakeners, Bolick calls hers. As for Nietzsche:

What have you up to now truly loved, what attracted your soul, what dominated it while simultaneously making you happy? … Your true educators and cultivators reveal to you the true primordial sense and basic stuff of your being, something that is thoroughly incapable of being educated and cultivated, but something that in any event is bound, paralyzed, and difficult to gain access to. Your educators can be nothing other than your liberators.

Citizens Not of Their Time

When a 20-something Bolick came across a portrait of essayist Maeve Brennan, it was like “looking into the future and discovering that my unremarkable self had somehow become a person of consequence”:

The same narrow shoulders, the same Irish features, slightly pointed without being angular…. Her expression reads somewhere between indifference and glower…. The scene radiates an austere, prideful autonomy that I suddenly, desperately wanted to inhabit.

Brennan would be the first of Bolick’s five awakeners; Neith Boyce, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Edith Wharton, and Charlotte Perkins Gilman would follow. These women, Bolick notes for The Atlantic’s “By Heart,” helped fill a gap left by her mother’s death in Bolick’s early 20s.

A lot of my questions were about finding a home in the world: Where did I come from? Where am I going? What kind of home am I making for myself? Once my mother died, my sense of home was lost, in a way, because I could never return to the life I’d shared with her. Going out into the world and accumulating these women was a way of creating my own home, whatever that would turn out to be.

These awakeners helped Bolick reach comfort and confidence about being never-married into her 40s. Each of them also married. Bolick addresses her seemingly unintuitive affinity for the title “Spinster” in the book, but it also bears noting that if women like Brennan, Gilman, and the rest had come of age today, their marrying would’ve been far from a foregone conclusion. It’s much easier now for women to thrive financially and professionally on their own, to have sex outside of marriage without condemnation, and even to have children without involving men.

These awakeners helped Bolick reach comfort and confidence about being never-married into her 40s. Each of them also married. Bolick addresses her seemingly unintuitive affinity for the title “Spinster” in the book, but it also bears noting that if women like Brennan, Gilman, and the rest had come of age today, their marrying would’ve been far from a foregone conclusion. It’s much easier now for women to thrive financially and professionally on their own, to have sex outside of marriage without condemnation, and even to have children without involving men.

Bolick’s awakeners were, in other words, untimely.

Untimeliness was, for the then-little read and littler appreciated Nietzsche, a point of pride. He declared that the “public opinionators” of his day would be forgotten or considered embarrassments by future generations, because they were too “lazy” to be themselves and embrace their individuality over what was fashionable.

How hopeful, by contrast, can all those people be who do not feel that they are citizens of this time; for if they were citizens of this time, they too would be helping to kill their time and would perish with it—whereas they actually want to awaken their time to life, so that they themselves can go on living in this life.

We may acknowledge that “just do you” is advice of limited utility if institutions like patriarchy actively hold you back. Still: while Brennan et al. may not have entirely achieved their Platonic ideals for the good life, they were nothing if not proudly, relentlessly, sometimes furiously themselves, striving to awaken their times. And it is for this, their being otherwise than what they were supposed to have been, that they could be Kate Bolick’s educators.

It’s also what made sometimes their examples problematic: she latched onto them “as if the economics and politics of their day weren’t so entirely different from mine, as if a person can have a wish about what her life could be that’s divorced entirely from context.”

Possible Selves

Outside of college English departments, the names of even Bolick’s best-known awakeners may trigger only faint recognition. That Bolick needed a combination of improbable luck and years of dogged research to properly assemble them all illustrates “the necessity of increasing culture’s store of heroines”—models for possible selves, in the parlance of a social psychology study she cites. She adds in an interview: “We don’t have a vocabulary or a well of images that are authentically reflecting who the single person can be in a positive light. Even though we have more single people than ever before, we still see them as novelties or a topic, rather than just a person.”

As an Asian-American screenwriting student who’s spent the better part of the last decade stumbling in the general direction of being a decent feminist, I spend a lot of time thinking about representation in pop culture. In this realm, Bolick’s observation is true not only for women and single people, but also for LGBTQ folks and people of color.

It’s not a terrible exaggeration to say that my high-profile pop culture surrogates boil down to John Cho characters. There’s Sulu in the rebooted Star Trek, of course, a cool-headed badass with little that’s stereotypically “Oriental” about him. Henry Higgins on the short-lived Selfie was also pretty great—an Asian romantic lead on a network sitcom, sympathetic and complex, again not defined by his race. But how many more characters like Henry can you name in a minute? If you need more than one hand to count them, do let me know.

This is admittedly a different problem from untimeliness. But the result is the same for all minorities: a lack of highly visible contemporaries and just-a-generation-or-two-removed role models to show a wide range of possible good lives.

“A Template for My Own Future”

I find at least a partial solution in Bolick’s “By Heart” contribution, where she explains why she doesn’t consider her awakeners aspirational figures: “They were completely distinct entities that I engaged and interacted with by bumping up against. Engaging with them allowed me to think about my own life from different perspectives the way great conversations do.” She says in Spinster that her conversation with Maeve Brennan—not only seeing the world as Brennan saw it, but also seeing Brennan as others saw her, and finding things Brennan’s contemporaries missed or ignored—amounted to “cobbling together a template for my own future.”

For Nietzsche’s part, “Schopenhauer as Educator” emphasizes not Schopenhauer’s philosophy but “Schopenhauer’s way of expressing himself…. how to express with simplicity something that is profound, without rhetoric something that is moving, and without pedantry something that is rigorously scholarly.” Nietzsche wants not to live by Schopenhauerian prescriptions, but to be Nietzsche as mightily as Schopenhauer was Schopenhauer—to live with the same honesty, clarity, and rigor, “in thought as in life.”

Similarly, Bolick’s other awakeners illuminated specific, still-relevant concerns: sexual relationships as something you have rather than something you are, the logistics of singledom, the invisible importance of how architecture and design shape not just space but living. (Imagining Boyce’s apartment: “A place as clean and uncluttered as a finely made decision.”) Whether or not Bolick reached the same answers, the real gift was hearing the questions.

And she finds in Brennan her own exemplar for clarity: “To write a sentence, then a paragraph, then another, and to have someone else read those lines and immediately understand what I meant to express—I wanted to try to do that.”

In this, at least, I have many educators indeed, Nietzsche and Bolick among them. But they can only be my liberators. They can only help me find my own wherewithal to write my own stories—figuratively and literally—that may go some small distance toward answering the call for a greater store of people in whom all our descendants and successors might more easily glimpse their possible selves.

LikeLike

Pingback: [Applied Sentience] Awakeners and Liberators: Kate Bolick’s Nietzschean Education | Omelets for Pepper·

Pingback: Putting Stories in Context: Conversation with a Culture Critic, Part II | Applied Sentience·

Pingback: Putting Stories in Context: Conversation with a Culture Critic, Part II [APPLIED SENTIENCE] | Omelets for Pepper·