Empire “Masterpiece” #144 / Issue #318 / December, 2015

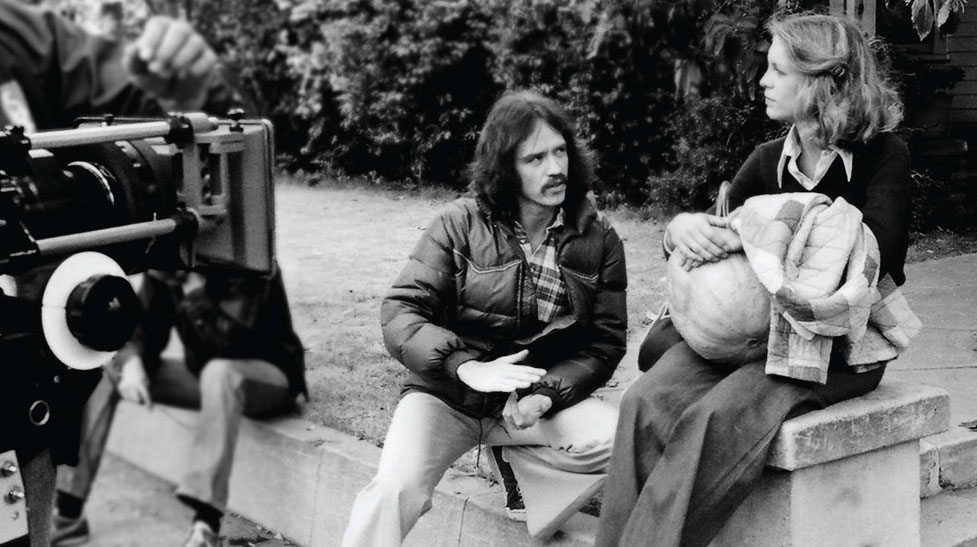

It’s all there in the opening minutes: Halloween is about the music and the Panaglide. Three piano notes and a weird time signature are all the film requires to create immediate tension over a black screen with a steadily approaching pumpkin. Halloween is a small film, but that big theme will echo for decades. Cut next to the opening flashback sequence, which sets up the film’s technique as well as its context. John Carpenter’s music will unsettle, and his camera will prowl. In some ways there’s no more to the film than this, so direct is its agenda.

As a film that immediately spawned copious sequels and imitators, Halloween often feels like a beginning: the moment when a new type of horror came to brush away the genre’s cobwebs. This isn’t exactly true. It was released in the same year as Dawn of the Dead; a year after The Hills Have Eyes; and four years after The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. George Romero, Wes Craven, Tobe Hooper and David Cronenberg were already making horror inroads while Carpenter put together a loopy sci-fi (Dark Star) and an intense lo-fi thriller (Assault on Precinct 13). Halloween is Carpenter’s arrival into a genre and peer group with which he’d forever be associated subsequently, but he didn’t get there first.

He was, however, immediately a part of that vanguard. Two years before Halloween, Hammer made To The Devil a Daughter, a late gasp from a company at this point doing better with On the Buses. So there’s a real sense of a new guard replacing the old, and the ushering in of a new era that perhaps began with Romero’s Night of the Living Dead. Halloween is when that underculture breaks into the mainstream.

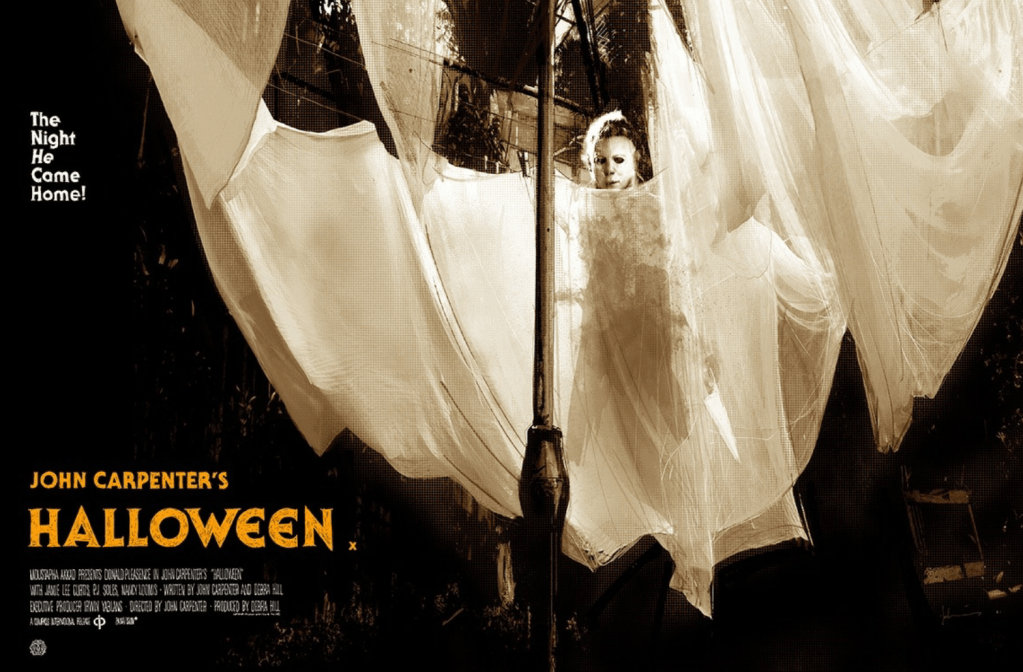

It isn’t even the first slasher film (not least because there’s barely any slashing and practically no blood). Black Christmas probably has that honour, although the subgenre’s roots are in Psycho, giallo and the splatter films of Herschell Gordon Lewis. Even Hammer had played with proto-slasher tropes in The Mummy’s Tomb and Hands of the Ripper. Those progenitors though, were often whodunnits. Halloween reveals its murderer in the first scene, and is one of the first films in which the killer is barely explained. We’d had cannibal clans, serial killers, zombies and ancient Egyptians, but Michael Myers, despite having a name, is conceived more or less as simply an entity. In the credits he’s listed only as The Shape.

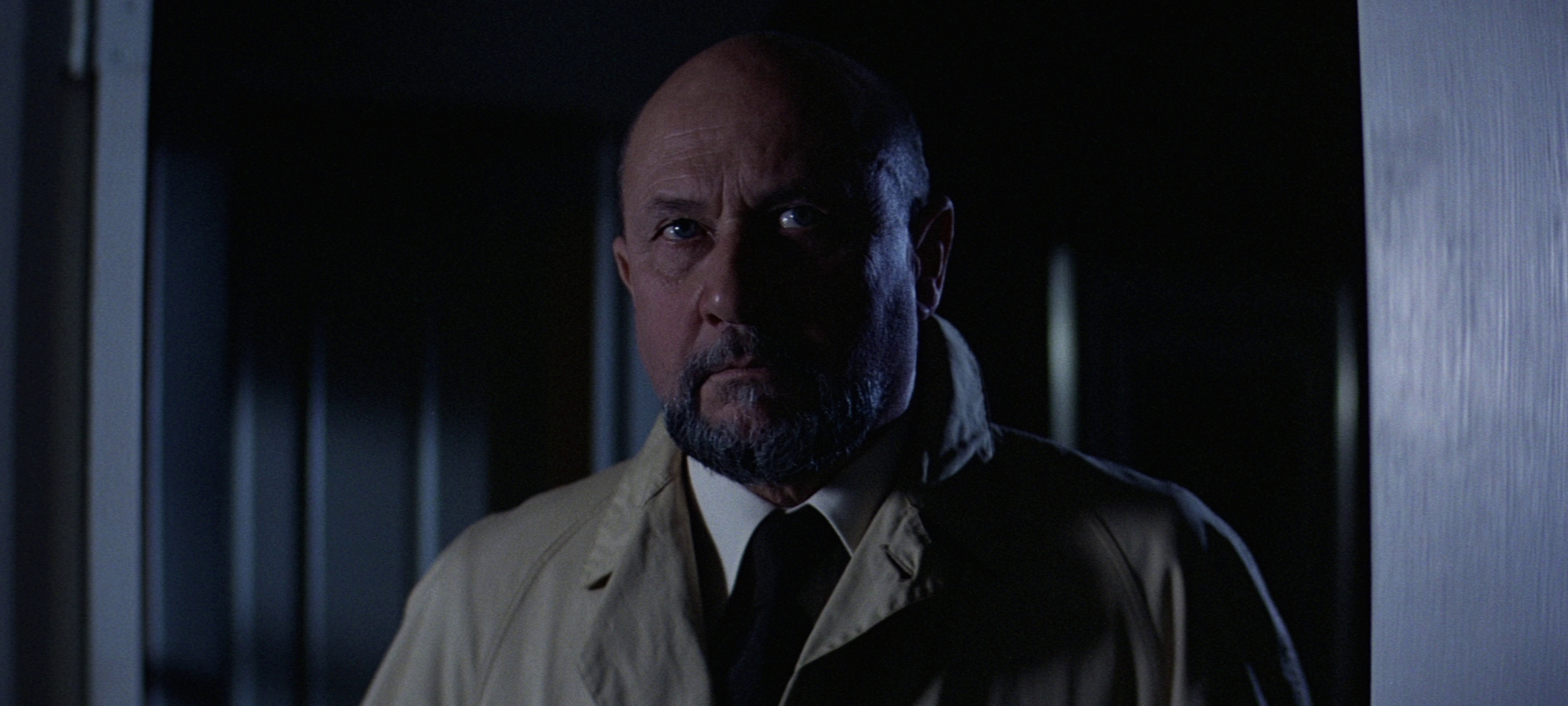

Donald Pleasence, cast as the elder statesman in a film full of new faces (Christopher Lee turned it down) told Carpenter he didn’t understand the Halloween screenplay. You can sympathise. On paper, Myers as a character makes little sense. Having spent much of his childhood and all of his adolescence in an asylum, he nevertheless knows how to drive and has the ability to knock out phone lines. Over the course of the film he is blinded, stabbed and shot, seemingly to no effect, despite his being set up as explicitly not supernatural. In the film’s dialogue he is much talked about, but the set-up is about who he is, not what he is. In his boiler suit and Shatner mask, he seems to arrive fully formed: both twisted man-child and elemental boogeyman. The sequels will pick endlessly over his true nature – he’s Laurie’s brother; he’s the product of a mad druidic cult; he’s haunted and controlled by his dead mother and his younger self – but the original Halloween’s purity is that Michael Myers just is. “The evil has escaped,” says Dr Loomis. Evil is enough.

So it’s easy to miss that there are actually establishing scenes for the outfit and the face. The overalls have come from the unfortunate owner of the Phelps Garage truck that Pleasence finds abandoned. The mask comes from a break-in at a hardware store that seasonally stocks Halloween gear (although that seems to happen after we’ve already glimpsed Michael in full kit). There’s also an element in this original film that the sequels barely, if ever, pick up on or run with. October 31st is important, not just as a Myers anniversary and a date for the carnage, but for the character of Michael himself. Throughout this film, he’s a prankster: not great on the treats front, but certainly full of tricks. He hides in a cupboard, plays dead, dresses in a sheet. “It’s Halloween: everyone’s entitled to one good scare,” says Sheriff Bracket. Michael obviously agrees. He even sets his victims up in gruesome tableau with his murdered sister’s headstone. Surprise!

Counter-intuitively, it’s these oddities that make the film bite. Superficially a straightforward affair – Carpenter says its pure simplicity was key – the film gets stranger the deeper you dig. Why does Loomis visit the graveyard? Just how big is Haddonfield? Why does it appear to be spring? Critics have looked for meaning and metaphor, reaching for rot at the heart of suburbia (later the underbelly of Elm Street) or the fact that the promiscuous girls die first. But these theories are awkwardly mapped on to a film that determinedly provides no answers for people looking for logic. Jamie Lee Curtis’ unusual ‘final girl’, for instance, doesn’t have sex during the movie, but is as interested in boys as her friends (the object of her affection, Ben Tramer, singularly fails to get lucky in Halloween II). And while she appears frumpy on the surface, she’s rebellious enough to smoke weed in the car, and we’re given no sense that it’s under peer pressure.

So don’t approach Halloween expecting sense. Do expect suspense. The pace is measured, with long, quiet sequences and lengthy walks and drives from one location to another. Each moment is stretched as long as possible, and phone conversations are important. Even the best scares are muted: there’s no fanfare on the soundtrack when Myers sits up behind Curtis, and no sound at all as he stares at a hanging corpse like a baleful hound. There are no elaborate kills here. Carpenter was aiming for Hitchcock. That he inspired Friday the 13th is Halloween’s darkest irony.