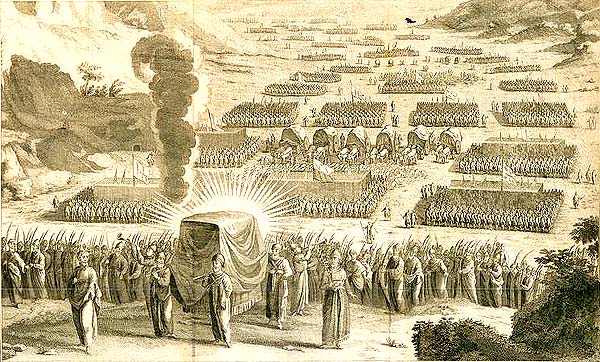

The Israelites are on the move in this week’s Torah portion, Beha’alotcha, as they pick up their journey through the Wilderness to the Promised Land. It is quite a logistical ordeal, moving that many people along with all of their belongings, not to mention all of the communal property, primarily the Tabernacle, their central sanctuary which can be broken down and carried like Ikea furniture. The Torah goes into some detail as to how the tribes are to organize as they travel, and who is meant to carry what.

A long quote, but stick with me:

In the second year, on the twentieth day of the second month, the cloud lifted from the Tabernacle of the Pact and the Israelites set out on their journeys from the wilderness of Sinai. The cloud came to rest in the wilderness of Paran. When the march was to begin, at the Lord’s command through Moses, the first standard to set out, troop by troop, was the division of Judah. In command of its troops was Nahshon son of Amminadab; in command of the tribal troop of Issachar, Nethanel son of Zuar; and in command of the tribal troop of Zebulun, Eliab son of Helon. Then the Tabernacle would be taken apart; and the Gershonites and the Merarites, who carried the Tabernacle, would set out.The next standard to set out, troop by troop, was the division of Reuben. In command of its troop was Elizur son of Shedeur; in command of the tribal troop of Simeon, Shelumiel son of Zurishaddai; and in command of the tribal troop of Gad, Eliasaph son of Deuel. Then the Kohathites, who carried the sacred objects, would set out; and by the time they arrived, the Tabernacle would be set up again. The next standard to set out, troop by troop, was the division of Ephraim. In command of its troop was Elishama son of Ammihud; in command of the tribal troop of Manasseh, Gamaliel son of Pedahzur; and in command of the tribal troop of Benjamin, Abidan son of Gideoni. Then, as the rear guard of all the divisions, the standard of the division of Dan would set out, troop by troop. In command of its troop was Ahiezer son of Ammishaddai; in command of the tribal troop of Asher, Pagiel son of Ochran; and in command of the tribal troop of Naphtali, Ahira son of Enan. Such was the order of march of the Israelites, as they marched troop by troop. (Numbers 10:11-28)

Quite a lot of detail; the Torah is into logistics.

In reading this description, one name might jump out: Nachshon son of Amminadab. Nachshon we are told is the leader of the tribe of Judah, and it is the tribe of Judah that is the lead tribe, the head of the processional as the Israelites march out.

The name Nachshon may be familiar because of a story found in the midrash (commentary) about the crossing of the Red Sea. Ancient midrash often time “fills in” gaps in the Torah narrative, or adds additional detail. In the Torah text, when we read of the Israelites leaving Egypt, the story tells how with the Egyptian army in pursuit, the Israelites come to the shores of the Red Sea. With destruction seemingly in front of and behind them, the Israelites cry out to Moses, and Moses in turn cries out to God. Nobody seems to know what to do in the moment.

In the Torah text, God instructs Moses to raise up his staff and part the seas for the Israelites to march through. But the midrash adds in a detail. Before Moses raises his staff, in the moments when no body seems to know what to do, the midrash describes how Nachshon jumps into the water. He is going to move forward towards freedom and away from oppression no matter what it takes, and it was his action, his decisiveness in a moment of indecision, that inspires Moses to act and the seas to part.

Nachshon, the one whose actions inspired the nation to move forward to complete the final act of liberation, is now the standardbearer at the front of the nation on its path toward normalcy.

Now granted the Torah predates the midrash by centuries, and it is possible (probable?) that the midrash tells the story of Nachshon at the Red Sea simply in order to explain why the tribe of Judah rose to prominence later on. But let’s read the stories in order and suggest the Nachshon’s high position is a reward or recognition for the risk he took earlier. His actions helped create a nation, and now he is honored for them. And Nachshon was able to transform his revolutionary act to established leadership.

In telling the story of Nachshon, we tend to focus on the shores of the Red Sea, on his first act. And we ask ourselves, what is our Nachshon moment? When are the times that we take a leap forward into the unknown, take a risk, move the bar, and do so without knowing what the outcome will be?

But what if, instead of thinking about the Red Sea, we focus on his second act in the Wilderness. And in regards to this we can also ask ourselves, what is our Nachshon moment? In other words, when are the times we were able to translate inspiration into actuality? When were the times we were able to lead not by leaps of faith, but by thoughtful planning and small steps? When were the times we were able to advance not because of an individual action, but by coordinated efforts, collaboration and deliberation?

Indeed, it is often by these Nachshon moments–the ones on land rather than those on sea–that we are able to affect real and lasting change.

Thanks for continuing the conversation!