Growing up FilAm, filling the holes in my heritage

By Daniel Griffith“Um, I’m Japanese! I think.”

… Was my response, walking up three flights of stairs past the library in the first grade, to that question: “So, what are you?”

That’s a fated question, which many to this day dread answering, even hearing. But it never bothered me.

Six-year-old me knew they were simply asking, innocently, ‘How are you different from us?’ But I never felt any different, and ‘Griffith’ didn’t sound that far from ‘Evans’ or ‘Parker.’

Still, searching in the moment for something that set me apart, I gave what seemed like an easy answer – Japan was where my mom was born, I’d done a report on it, I knew where it was on a map. Close enough, right? Right. Maybe I was just clutching onto the hope I’d catch the eye of the pretty, half-Japanese girl in my class.

Throughout school my ethnicity was a non-issue. As far as I was concerned, I checked the ‘White/Caucasian’ box on my standardized tests. Though most of his family was not present in my life growing up, my father’s name held precedent. I held myself up on that basis during most of my childhood.

One Chinese, two Indian boys, the aforementioned half-Japanese girl and I collectively formed the diversity in my lower school class. Being Filipino solely meant getting to call dibs during country presentations, bending the rules while writing Spanish essays (the Philippines was technically a ‘Spanish-speaking country’), and my mom cooking chicken adobo for multicultural week.

The limited extent of my Filipino-ness could be found in one place at our family parties: in between the stock adobo, pancit, lumpia on the buffet table and Lola and Lolo in the corner murmuring Tagalog words to each other.

I grew up, grew in to my ethnicity. Three young Filipinas who grew to be among my best friends helped fill holes in my heritage. At 16, my cultural awareness quadrupled as I was introduced to the principle of extended family like I’d never imagined it before.

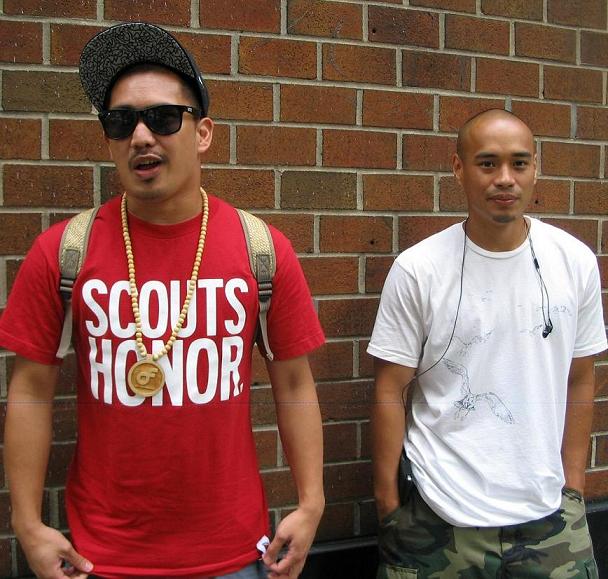

While living in Seattle, I followed the calling to discover more about my culture. Nearly everything I took part in had some connection with the Filipino community.

Shortly into my first year of college, I was able to talk, cook, play, gossip, and eat Filipino together with my Filipino friends. I was proud to come home and share with my aunties and Lola the kinship I’d found. Suddenly I could see the nuances that made us Filipino when I returned to the same holiday parties that I felt were once devoid of those tendencies. Having absorbed so much culture, it was becoming easy to label myself a Filipino.

I was fortunate enough for the opportunity to study abroad twice. I traveled to opposite ends of the globe, bringing my ethnicity with me. Studying in the Philippines was a natural choice, having had just a taste of Filipino culture and wanting much more. But despite my efforts to connect with the Filipino people as one of their own, there is so much in actuality setting us apart. I made many lasting friendships and connections, but only a few that reached beyond my pale skin tone.

In Argentina it was a bit simpler to traverse the urban landscape unnoticed; due to the heterogeneous population, looks are not meant to serve as basis for assumptions. I shared my heritage with anyone who would listen, eager to appear impressively multi-cultural. I even connected with the Philippine Embassy in Buenos Aires, which was a real international twist! However, my overly-critical ‘porteña’ host mother was frequent and quick to point out, “Why do you always talk about being Filipino? Aren’t you from the United States? You should be proud of being American.” I dismissed her then, not thinking about her words until much later.

As I’ve learned progressively more about myself, the easy answer is now to assert, “I am Filipino.” Just as it was once easy to call myself American, or even Japanese (though I’m not). But I’ve since learned not to take the easy way out. I’ve learned that the pursuit of self is about more than ethnicity, but identity – a product of self-perception, belief, and assertion. It’s about more than finding, but searching – to engage in a constant cycle of praxis with discovery and questioning at its heart. Every now and again I run into something that reminds me – I am a product of my father’s name and my mother’s family. And I work a little harder to understand myself as a Filipino American.

Pacific Northwest native Daniel Griffith is a regional director for non-profit Kaya Collaborative. He graduated with a degree in International Studies from Seattle University, where he served as president of the United Filipino Club. His international experience working and studying in Argentina, Honduras, and the Philippines has led him to pursue a career in international public service. He was born in Portland, OR, where he lived before moving to Seattle, WA. His father, who is Finnish /Welsh, has lived all across the U.S., from Pittsburgh to Denver, Walla Walla and Portland. His mother, born a Filipina citizen in Okinawa, lived in Japan before moving to Guam and finally to Portland to attend university.

Excellent blog post. I absolutely love this website.