Emmet Teran, Arts Editor

This interview marks the beginning of the Arts Section’s November Short Fiction Series. Each Argus issue in November will contain either an excerpt or an entire student story submitted to the contest. Be sure to check out the first piece coming out on Nov. 1.

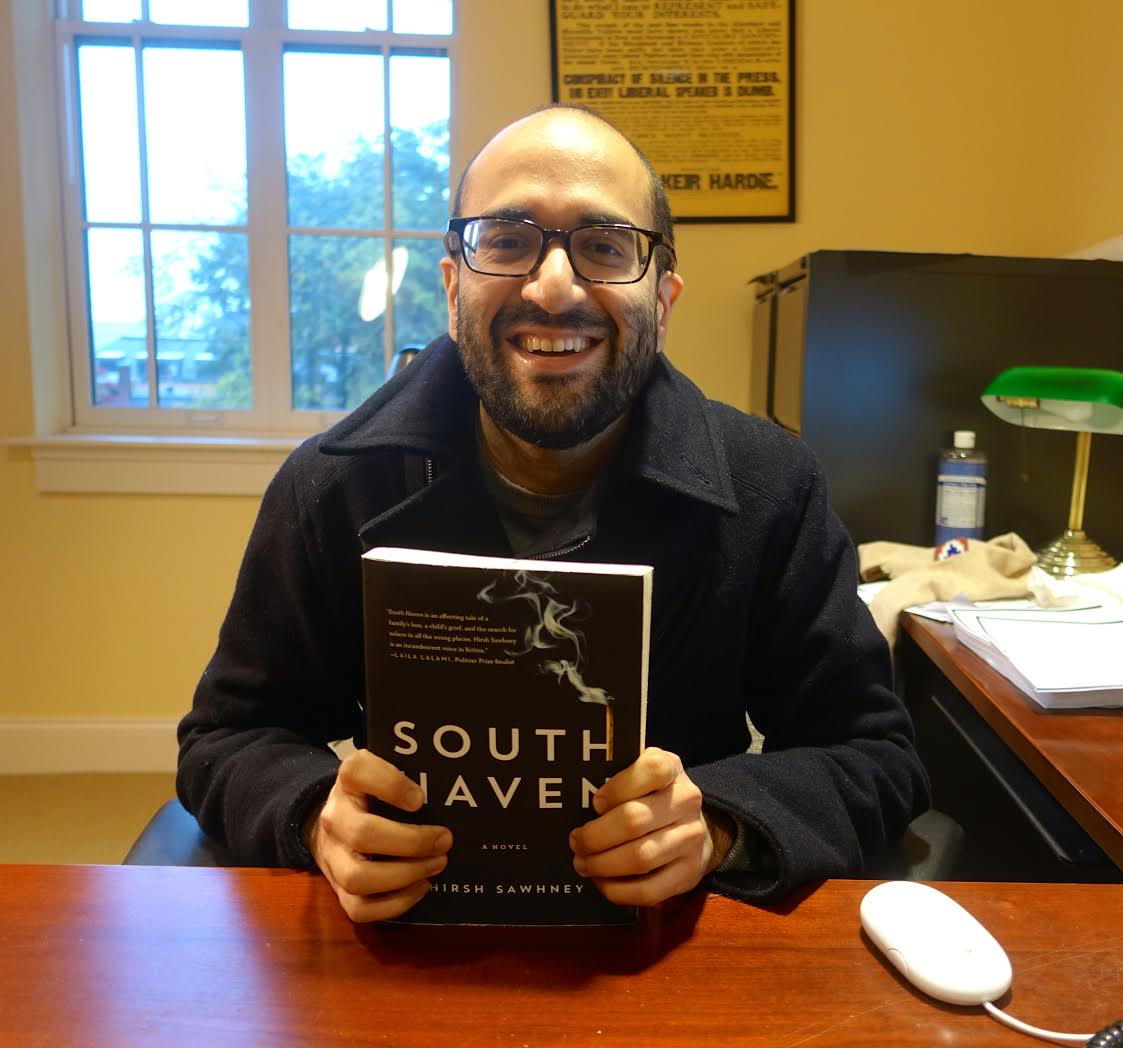

Assistant Professor of English Professor Hirsh Sawhney released his first novel this past April, titled “South Haven.” Sawhney has been at Wesleyan for several years now, teaching creative writing workshops and Special Topics literature courses. The novel, set in the early 1990s, delivers main character Siddharth’s journey through boyhood with his dysfunctional father, Mohan Lal, a college professor in a fictional southern Connecticut town. After the death of his mother, Siddharth faces challenges at school, the growing influence of a guidance counselor, Ms. Farber, and a college-bound politically active older brother. Sawhney’s “South Haven” situates the effects of a family death and Indian diaspora politics in the everyday lives of a highly nuanced cast of characters, all of which are set in a vast fictional world comprised of the colonial houses, town greens, and outlet restaurants that evoke quintessential New England suburbia.

The Argus had the chance to sit down with the new novelist this past month to discuss his work.

The Argus: You’ve edited a collection of short stories called “Delhi Noir” and you’ve written numerous book reviews for The New York Times. With a foundation in editorial and critic’s roles, how has it been making the transition from short-form fiction to a larger piece?

Hirsh Sawhney: All the work I’ve done in the media as a critic, as a journalist, as a reporter, as an editor, work in ways in which I can simultaneously pursue my craft as a writer and also earn a living. So all the while that I’ve been publishing pieces, I’ve been working on long-form stuff that often didn’t see the light of day. I think all of this has had an often-harmonious relationship. By editing other people’s work and helping shape their craft, you internalize so much. Doing short-form writing for good editors has given me such a great understanding of sentence structure, syntax, line and paragraph level stuff, and I really bring that with me. It defines my style as a writer.

TA: Are there any particular moments in your life that you view as an inspiration for “South Haven?” I read briefly in your author’s note that a classmate had committed suicide. Could you speak to that?

HS: When I was in junior high school, there was a young boy whose locker was next to mine. He was a nice person, quirky, and he was subject to a vast amount of bullying. I think that as a consequence of that bullying, though I’m sure there were other factors, he committed suicide. I felt that the whole community was culpable for being complacent for what was going on. Though I had a fine relationship with this particular boy, it just left me with grief and guilt.

Simultaneously, around this time in my life, the Indian American community in which I grew up was starting to dabble in what’s known as Hindu extremism, which is a form of right-wing, politically motivated Hinduism that is discriminatory in nature. Hindus in both the U.S. and in India were getting very involved with this noxious mixture of politics and religion.

In my late twenties, I started writing about these things very separately, and as it happens with the creative process, these two seemingly disparate ideas seemed to have so much in common for me personally. They overlapped and I realized that by studying them both together in fiction, I have learned something about myself and the world that surrounds us today, a highly global world in which diasporas have a pretty strong effect on not just their adopted countries but also their homelands.

TA: With a topic that’s so close to home, how was it attempting to find the necessary distance from your past to write, or did you tap into it as a form of inspiration?

HS: Well certainly in terms of setting I tapped into my direct experiences with not only place physically, but place sociologically in terms of the tensions: the latent racism, the change in economy, and the ways in which these impacted people’s ability to connect with one another. Maybe at the beginning of writing a novel, there’s a temptation to hold onto things that ring true with respect to my lived experiences, but my novel only worked and became what it was when I really let go, and allowed the reality of the book to become untethered.

TA: I have to ask about one part of the book that I really enjoyed: Mustafa’s Pasta Palace. Is this space based in memory? Because I found the development of the relationship between Mohan Lal and Mustafa to be incredibly fascinating.

HS: I saw a lot of Hindu Americans who seemingly had cordial relationships with Pakistanis because they shared such a common past. They were the same people before 1947, yet despite their knowledge of the other, they would harbor prejudices. Ya know, a suburban Italian restaurant in the New Haven area run by a non-Italian. Yeah, there were a few that I went to. The Pasta Palace was based on one of them.

TA: You create such complex characterization throughout the novel. What was it like developing these relationships without having such cut-and-dry, good-and-evil forces?

HS: It was tough for me to do. I failed at it a lot early on, certainly with respect to Ms. Farber because [Siddharth] doesn’t like her and the narrative voice stays close to this little boy. I had to write Ms. Farber from Ms. Farber’s point of view, even though I knew I would never include those sections in the actual novel. I had nothing against Ms. Farber. There was a lot of listening to my characters with a stethoscope, with a glass to the door. I really had to listen to her, and allow her to push back, and allow her to be flawed, but allow her to have sense. I think that’s the goal with a lot of fiction, a lot of psychological realist fiction. It’s also the challenge with it.

TA: What next? Are there any book readings planned?

HS: Yeah! I have a fall tour going on. My book’s being published in India in February so I’ll be in Delhi in March probably. I was in London over the summer. There’s been a lot of synergy in terms of working with a small independent publisher. They don’t always have the economic reach, but [Akashic Books], run by [alumnus Johnny Temple ’88], really does its best to get authors out there.

It’s a strange thing for a writer to be out there, engaging with work that’s finished and can no longer be changed. It’s thrilling and one has to be very grateful for the attention, yet these types of situations can be somewhat unnerving and not necessarily conducive to creating new work.

TA: Do you have any new pieces in the works at the moment?

HS: I just wrote a short story that I’m very happy about for Amy Bloom’s ”New Haven Noir” anthology. Amy and I really worked on some hard edits for that piece and I think it came out great. I’m doing some nonfiction work. I just wrote a long essay on the Indian novelist Aravind Adiga [published in The Times Literary Supplement]. I’m also at the very beginning stages of a novel. Who knows if the kind of beast I have in mind for this manuscript will at all end up being the final version.

That’s what I learned from “South Haven.” My novel emerged out of a short story. As you write, you learn about your own process. It’s great to have ideas for novels, but one shouldn’t get too intimidated or overwhelmed because once you actually embark on the creative process, you might end up departing rather drastically from the kernel or seed that’s motivating you to begin with.

Comments are closed