How does one achieve nirvana? By listening to the intense lyrics and heavy beats of hip-hop, of course. If you’re thinking that one has nothing to do with the other, you’ve clearly never had a conversation with Evan Okun ’13. The recent Wes alum is as passionate about Buddhist ideology as he is about killer rhyme schemes.

“Back Up, Black Out,” Okun’s newest album, puts these two seeming opposites together in an intricate examination of one’s existence in a world of racism, classism, and any other –ism that you may find in a Sociology class. From lyrics that take you on a walk to the Freeman Athletic Center, to ideas Okun discussed with Associate Professor of Sociology Jonathan Cutler, to the over 20 Wesleyan students and alums that contributed to the album, “Back Up, Black Out” is dripping with all things Wesleyan.

Okun sat down for a Skype date with The Argus to talk about the album, the good and bad of Wesleyan, and why we all need to black out.

The Argus: Can you tell me about where the album title came from?

Evan Okun: I’m really into Buddhism. [I] took an intro Buddhism class at Wesleyan in my freshman year, and since then I’ve meditated every day just because there’s so much hatred and ignorance in my own mind that I need to constantly unlearn. All the hatred that I find is based on my own insecurities, somehow. Even when I’m not hating someone, this type of ego, this self-protecting narrative that I refer to on the album, it gets in the way of really seeing anybody or seeing things that I love.

The idea of “Back Up, Black Out,” it comes from the song “The Feature,” and that song is all about light. Last year I was studying in SciLi from 4-8 p.m. I sat in the 24 hour room facing Olin. It was a beautiful day, and when I arrived, light from outside flooded my being. I was frozen in awe at how gorgeous a place Wesleyan was. As the sun set, I slowly grew less and less able to see what was outdoors, and instead, all I could see was my reflection in the glass. This prompted thoughts [questioning] how attractive I looked. I suddenly realized that this is a perfect way to understand the polluting effect of my ego. My ability to see beauty in life and in others is inversely proportional to the amount of spotlight I throw onto myself. It also depends on how much light there is in front of me – how much love I feel for the room I’m in and for the people I am with. For this reason, the goal of the album is to “Back up, black out, and give the feature some shine.”

A: I feel like classism is specifically something that’s brought up a lot throughout the album as well.

EO: Yes, one hundred percent. Professor Cutler allowed me directly to write my senior essay [for Sociology] on applying Buddhist theory to issues of race and class on this very interpersonal level, so [I applied it to] this class that I [taught] at the juvenile detention center near Wesleyan. But then it ended up applying to the school system in general. And that’s kind of what happened with the album—where the album was about Buddhist ideas of egocentricity, but then I think egocentricity is at root for all societal oppression. You really start to attach and think that you own that which you see near you, but you have no ownership over any of it. So that comes on “The Ripple,” which is on the second half of the album as it gets more and more intense.

I’m confronting the mom on the album—who’s nothing like my actual mom; my actual mom is beautiful—but I confront her being like “none of what you have is yours.” One thing that really bothers me is this idea of the way liberal, progressive institutions can successfully coexist and thrive in an oppressive society, which happens all the time. Wesleyan is included in that. I, myself, and my constant inaction is included in that. If there’s no action component, then it’s just so painful to see how the talking without any action is pervasive. And so then I’m like, “You think praying for them is enough, Mom? How about you give everything that still isn’t yours back?” And then the next verse is ironically how I learned that whole idea at college. I also try to critique academia in there a little bit.

A: That’s interesting, especially being a recent Wesleyan alum, that you reflect on your Wesleyan experience both positively and negatively.

EO: Oh yeah, my whole senior essay was about the education system. I got a certificate in education too, and my sister’s a teacher. I think about education all the time.

A: Can you tell me a little bit more about the female voice that appears on the album? Is she representing more than just a mom?

EO: That is in no way supposed to represent any human being who I’ve ever met….In Professor Cutler’s class called Paternalism and Social Power, which is mind-blowing, we read something about how in the 1970s there was a counter-culture and it was supposed to be so amazingly progressive at dismantling systems. But then what happened is [that] the bourgeoisie institutions that were in place completely absorbed the counter-culture, and so you had the very successful, peaceful coexistence of progressive ideology and societal oppression. So [the voice] is supposed to represent that era, though she kind of sounds like a 1950s housewife, but [is] in the context of now, where it’s like, “I am progressive, but honey, you can’t think about that—it’s going to get you down.” So the voice in your head that says you don’t really have to try as hard as you want to.

A: Musically it also worked as a great interlude from one track to another.

EO: One thing about the theme I was talking about, light, is how if you get too much shine on your own ego and you’ve looked too much at yourself then you’ll be distracted. That idea comes from Buddhism, where everything that we are is reflected through us. Any words that I’ve ever said, I had to have learned it rather than create it myself. I did really subtle things throughout the album where I would use ideas, concepts [from others].

The inclusion of the mom’s voice was supposed to be a reflection of Kendrick Lamar’s recent album, “good kid, m.A.A.d city,” which showed a day in his life, and then he was constantly dialoguing with his mother and father. When light’s reflected, it comes back exactly how it was shot in. When it’s refracted, it goes into the reflected device but then bends and becomes something different. So the whole album is supposed to be something that I’ve reflected, but then refracted and changed, because [Kendrick’s] mom isn’t my mom. That’s what the first song [“Boom, Bang”] is about.

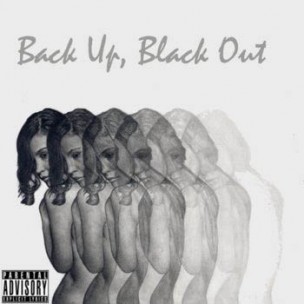

A: I love the cover art. Who designed that?

EO: The cover art is completely done in pencil, no computer effects at all. This artist named Jordan Boxer does drawings exclusively in pencil, including colored pencil as well. He’s friends with Paulie [Lowther ’13]. Jordan was meeting up with Paulie and we said “Whaddup,” and then Paulie was like, “Yo Evan, this dude’s the ill artist.” And then he showed me that picture for the album art that he had just finished two days before. Meanwhile I’m thinking that my album is going to be called “Back Up, Black Out” and it’s a picture of a girl backing up. Things are meant to be.

A: Do you think you’re going to keep doing music? What’s next?

EO: So I’m going to Chicago because I got a grant from Wesleyan to work for a program called Circles and Ciphers. They do restorative justice through hip hop. They work with juvenile inmates, kids in group homes, and local high schools in Chicago, and they approach issues of gang violence, loss in community, and a variety of issues through hip hop. So yes, I’ll definitely be doing rap all the time.

A: What a perfect job for you! Do you think you’ll put out another album?

EO: With music it’s hard, because I envision so many different albums. Right now, at these very preliminary stages, I have a lot written just because I love writing all the time. I think it’s going to be an album where it’s me, Sam Friedman [’13], and Nate Mondschein [’12]. They’ll produce it, and then I’ll be rapping on it. I think it’s going to be six tracks long, and it should be done by January.

A: Do you have a favorite track?

EO: I really like the fourth track [“Nadie’s Faded”]. The fourth track is for people in my neighborhood pretty explicitly. Not that I don’t want anyone to vibe with it, but what’s cool about putting this album out when I’m from my neighborhood, but putting it out to Wesleyan kids, too, is that I can predict what Wesleyan kids will like and what kids from my hood will like, and often times they won’t like the track that the other one likes. I mean, maybe you are fond of the fourth track. But it’s just like this battle rap, pretty hood. In my neighborhood, that’s their favorite track. I like all the songs, to be honest. I worked so hard on it, and conceptually it’s all together.

I really hope this album is one that listeners can vibe with as one entire piece, rather than individual tracks haphazardly thrown together. As people vibe with it, certain tracks will definitely stand out, but I imagine these will change depending on their mood on a given day.

A: If you were going to give advice to someone who just got to Wes who isn’t necessarily a major in the arts and wants to do their own project, what would your advice to them be?

EO: My advice would be to ask people what they love to do. That’s what I did. Anyone you meet, because you meet so many people as a freshman, and you don’t remember their names because you’re meeting everybody. What you will remember is their face and what you talk about, if you talk about something substantial.

The second question I would ask after what’s your name is “What’s something you love to do in the universe?” or “What’s something you’re so happy exists?” And then they’ll be like, “I love a cappella singing.” And you’ll be like, “Oh, I rap! Wanna jam?” Within like two days I was jamming with multiple people, a bunch of whom were on my first album. Just really collaborating is the way to do it.

You can try to do things alone, but people get bored….I love the album because I love listening to beats made by Wesleyan kids..It’s because of Wesleyan that every single track happened. There’s a Wesleyan kid directly involved in every single beat on the album. The only one is the middle one, which is the seventh track, which is my sister, but that’s because I love her a lot.

A: I love that it’s collaborative. I think that’s such a huge part of Wesleyan: you don’t have to wait—you can do it now. You have the resources; just go.

EO: One thing I would say is that what you love to do outside of the classroom can be brought very easily into the classroom. I wrote final papers on the juvenile detention center, on music therapy. I did an entire class that culminated in my senior recital with a Buddhism professor. It was just me, a Buddhism professor, and a professor in the music department. So I would work on music with the music guy and my ideas of religion and understanding of Buddhism with this Buddhism professor.

All it takes is you wanting to do it, and then they just let it flow. It’s incredible.

Back Up, Black Out by E. Oks is now available on Bandcamp. The album would not have been possible without the following Wesleyan students and alumni:

Sophie Becker ’16, Rashad Coleman ’15, Sam Friedman ’13, Coral Foxworth ’15, Marguerite Suozzo-Golé, Cherkira Lashley ’15, Paulie Lowther ’13, Tory Mathieson ’14, Lucas Turner-Ownes ’12, Jared Paul ’11, Jason Reitman ’15, David Stouck ’15, and Quasimodal a cappella group.

The online version of this article was updated on September 3 to correct an inaccurately reported quote in Okun’s answer to the first interview question . The article originally quoted Okun saying, “This prompted thoughts of how attractive I looked.” The article was also edited to correct information regarding where Back Up, Black Out is available. The article originally said, “Back Up, Black Out by E. Oks is now available on SoundCloud and Bandcamp.”

Comments are closed