During the early 2000s, the University’s campus underwent significant change. Between 2000 and 2002, Clark Hall was gutted and modernized, while Zelnick Pavilion was constructed between the ’92 Theater and Memorial Chapel. From 2004–2005, Freeman Athletic Center received a sleek, modern addition, Fauver Field was filled with Bennet Hall and Fauver Apartments, and Downey House was modernized. Plans for a new University center had been in the works for quite some time but were not realized until the Suzanne Lemberg Usdan University Center opened on Aug. 24, 2007, replacing McConaughy Hall (MoCon) as the primary dining hall and Davenport Campus Center as the intended center of student life.

These additions to campus are something that many current students take for granted, despite the drastic changes that they have brought to the campus’s atmosphere. But at the time, of course, the new construction sites and impending demolitions were the talk of the town. Everyone had an opinion.

“[Fauver is] not ‘Wesleyan,’ but it’s a nice addition to the campus,” Rina Han ’06 remarked in a September 2005 Argus article.

Others were upset by the transformation underway.

“I think [Zelnick Pavilion is] emblematic of the corporatization of Wesleyan…. The pavilion is sloppily sterile,” Sam Fleischner ’06 wrote.

Students perceived that this sterilization of campus extended beyond the University’s construction plans. In October 2006, the graffiti in the then-open part of the tunnels under Butterfield B were painted over. In response students created the Facebook group “KEEP WESLEYAN WEIRD” complaining about the push towards a more-censored University. Almost immediately after the tunnels were painted over, the graffiti was replaced by students with messages such as “Creativity should not be stifled” and “Take my Pictures ARGUS.”

A former student reflected on how the experience affected him.

“For me, it was a personal issue,” Joseph John Sanchez III ’07 wrote in a message to The Argus. “When I was visiting Wesleyan, a guy on rollerblades in a ‘Nobody knows I’m asexual t-shirt’…popped out of a tree and invited a bunch of pre-frosh on a tour of the tunnels. I have often cited that as the moment I knew I wanted to come to Wesleyan.”

The graffiti incident of 2006 was, to many, a symbolic incident, indicative of the ways in which the University was changing. It ignited vocal opposition.

At this point, the Fauver residences were newly in place, and Usdan was still under construction. These dramatic changes to the campus set the stage for the backlash against the further sterilization of the campus and its culture.

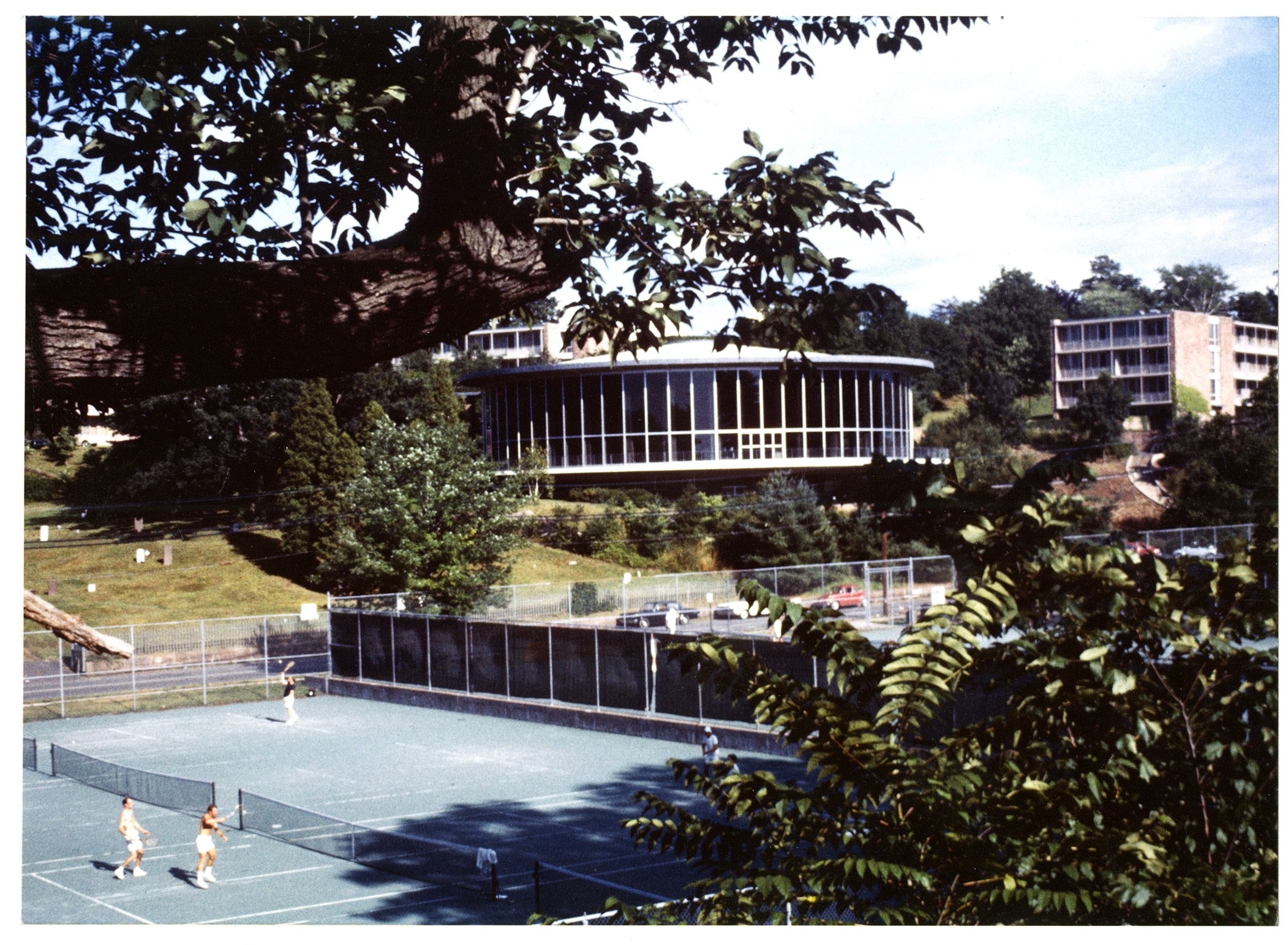

With Usdan on the horizon, MoCon was set to close. The UFO-shaped building behind Foss Hill had been a staple of campus since 1962, and its closing was a significant change to campus culture. One important feature of the building was the one big room in which everyone ate, which gave MoCon a sense of shared experience that Davenport lacked with its multiple floors and no clear line of sight. The balcony was also crucial, as students used it to make announcements. In 2003, the University prescribed the demolition for MoCon following the creation of the new student center, and while this wasn’t immediate, it eventually happened in 2010.

MoCon was remembered affectionately for being somewhat disgusting. As opposed to the crisp, sterile architecture popping up over the course of the decade, MoCon was grimy and charming. Students were still fond of MoCon and the sense of community it provided.

“We all have our own MoCon memories…,” Britany Mitchell ’07 wrote in a May 2007 Argus article. “We remember, for some of us with horror, the first time we [realized] that we would be eating the majority of our meals there for the better part of a year…. Although we may still have MoCon-smell in our clothes for several years, it was an important part of our Wesleyan experience.”

Alumni were also saddened by the news of MoCon’s demolition. Many came together in the Facebook group “Save MoCon” to share memories of the building.

“The smell of [M]ocon the morning after a good party or concert—an acrid mixture of stale cheap beer and human sweat—testament to a well-used…living space,” Stuart Remensnyder ’84 noted in a Facebook post.

This Facebook group also provided an avenue to brainstorm potential uses for the old dining hall, like an indoor park, a “giant aquarium” and “PLASTIC BALL PIT!! PLASTIC BALL PIT!!!” Alumni also used the group to complain about the direction of barren architecture on campus.

“What has the University come to that all the new buildings look like Olin Library?” Danièle Bučar Côte ’96 remarked in the Facebook group. “I always thought MoCon was ugly, but it had personality, at least…. If they want to demolish something, they should demolish the Foss dorms.”

Usdan opened in 2007, boasting a coffee shop, an IT store, and an ATM. In the weeks following its opening, it was the recipient of complaints across campus.

“Are we better off than we were before? The new mall on campus…has for better or worse shifted the flow of campus,” Louis Langlois ’08 wrote in an Argus article at the time.

“[There’s] this prevailing fear that the new Usdan symbolizes a new Wesleyan,” Sally Lee Rosen ’08 wrote in September 2007.

“This is conservative architecture at its worst,” Hunter Craighill ’09 wrote. “By trying to appease all parties involved, it ended up with no interesting architectural characteristics…. While many people criticize the CFA [Center for the Arts] and MoCon for being too outlandish, at least those buildings make an effort to push the limits. At least those buildings weren’t toned down to the point that they are boring so as to not offend anyone.

Students weren’t the only ones to comment on the University’s new addition.

“Looking at the bland off-white color scheme and the slick banners hanging from the rafters, the place reminded me of an airport,” Professor Jacob Bricca wrote in September 2007. “LCD monitors everywhere; a little store stocked with items for tourists; long lines for expensive food. I stepped back outside onto Wyllys Ave. to reassess. The only things visible through the glass were an ad for Mac OSX coming from the computer store and a big, glowing Bank of America ATM. Was this a mall or a university?… Why does the Wesleyan that I knew as a student…seem so at odds with this cold, bland, unappealing place? How does a university as unique and classy as Wesleyan end up with such a generic building?”

Concern over this new aesthetic extended beyond Usdan, prompting anxiety over the future of the University’s landscape. Alumni voiced their concerns regarding the construction of a new science building which, at the time, was set to begin construction in 2024.

“The school is in the process of building a new science building and I want everyone to be informed about the design,” Craighill wrote. “If you don’t like the design, make some noise about it.”

Another editorial, this one anonymous, complained about the series bland buildings that had been recently built on campus:

“The University won’t be winning any awards for seamlessly integrating a new building in between old ones anytime soon, if prior attempts with the architecturally bewildering Zelnick Pavilion, the blandly sterile Fauver Residences, and the visually lackluster and functionally disappointing Usdan University Center are any indication.”

In the years since Usdan opened, it has functioned well as a student center. However, it lacks the individualistic character of the University’s architecture. The CFA, Exley Science Center, MoCon, and other buildings that had popped up in the ’60s and ’70s were all distinct. So distinct, in fact, that in Thomas Gaines’ 1991 work, The Campus as a Work of Art, Wesleyan is mentioned.

“[Wesleyan] houses specimen examples of all architectural styles, but without an artistic focus,” Gaines wrote.

While the more conservative buildings arguably bring a sense of cohesion to campus, some find that the University’s eclectic architecture embodies its charm—and keeps it weird. Change, however, is natural. As Wesleyan grows as a school, some buildings obviously must be remodeled to meet the needs of students.

Nonetheless, it’s pertinent to ask if these changes come at the cost of the authenticity of campus spirit.

Bodhi Small can be reached at bsmall@wesleyan.edu

-

johnwesley