Establishing Park View — Part V: Restrictive Covenants and the Growth of the African American Community

According to Prologue DC’s Mapping Segregation research:

As Washington grew in the early 20th century, developers commonly sought to shape the character of new neighborhoods by including restrictive covenants (agreements) in deeds for the properties they sold. They might require that only single-family houses be constructed or that buildings be a certain distance from the street. They also might prohibit use of the property as a school, factory, or saloon―or prohibit its sale or lease to certain groups, most often African Americans.[1]

Because deeds are legal contracts, homebuyers needed to pay attention to what they were agreeing to. Buyers who ignored a covenant risked being taken to court, and racial covenants deterred African Americans from moving into new neighborhoods. Covenants also targeted other groups, including Jews. In DC this was more common west of Rock Creek Park.[2]

Starting in the 1920s, racially restrictive covenants also began to be imposed in another manner. Neighborhood associations would gather signatures on petitions that put covenants on the property of each signer, effectively restricting entire blocks. These petitions, which were filed with the Recorder of Deeds as legal contracts, could restrict whole neighborhoods, like Mount Pleasant and Bloomingdale.[3]

Ray Middaugh’s firm Middaugh & Shannon was one such firm to include racial covenants it the deeds for many of the houses they developed, not only in their Park View subdivision but also in the houses they developed in nearby Bloomingdale and other neighborhoods where they were active. Park View, similarly to Columbia Heights, Bloomingdale, and other near in neighborhoods, began their existence as whites-only neighborhoods in close proximity to black communities. Like Middaugh & Shannon, many developers of these neighborhoods often included restrictive covenants in their deeds ostensibly to “maintain” the neighborhoods property values. At the time, it was widely believed that neighborhoods needed to be racially homogeneous to be stable. So widely held was this belief that the Federal Housing Administration institutionalized the practice in the 1930s.

Map showing demographics in Park View, Pleasant Plains, Columbia Heights, Le Droit Park, and Bloomingdale in 1934. Also shown are locations of known legal challenges to restrictive covenants and the general area of Middaugh & Shannon’s Park View development (outlined in red). Map from Mapping Segregation in Washington DC, Legal Challenges to Racially Restrictive Covenants,Prologue DC, 2015, available at: http://prologuedc.com/blog/mapping-segregation/

The racial homogeneity of Park View began to change less than twenty years after its construction. This was due to a number of factors including the community’s close proximity to Howard University to the south, and an old, established African American community located west of Georgia Avenue and extending as far north as Park Road. Because of these factors, the change of Park View from a white neighborhood to a solidly African American neighborhood began in the south and gradually moved north. This change did not go unchallenged, with the earliest court cases enforcing restrictive covenants occurring on the 400 block of Columbia Road in 1936 (417 Columbia Road, NW — Parker v. Smith; Parker v. Bruce), 1937 (411 Columbia Road, NW — Parker v. Robinson), and 1938 (419 Columbia Road, NW — Fritter v. Brown; Fritter v. Cohen.).

Successive court cases occurred in 1940 at 426 Irving Street, NW (Williams v. Proctor; Williams v. Miller), in 1944 at 3310 Park Place, NW (Atkins v. Tate), and in 1945 at 3531 Warder Street, NW (Marth v. Matthews) before reaching the Princeton Heights subdivision at the northern end of the neighborhood in 1947. However, unlike the cases in the 1930s, those filed in 1940 and later did not result in the enforcement of the restrictive covenants.

The change of the Park View subdivision within the greater Park View neighborhood from a white community to a black community coincides with the period just prior to when challenges to racial covenants were being argued before the Supreme Court. The first black families to purchase houses on the 400 blocks of Luray Place, Park Road, and Manor Place did so in 1944, with the earliest known sale occurring on Manor Place in January of that year. This was four years before the Supreme Court would ultimately decide that restrictive covenants were unenforceable.

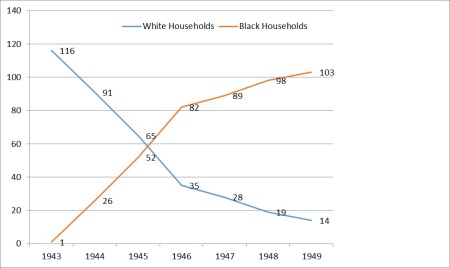

The change in home ownership on Luray Place was particularly swift and notable, with 45% of the houses being sold to black families in 1944 and 66% of the houses owned by black families by the end of 1945. Overall, a full 76% of houses on Luray Place, Manor Place, and Park Road were owned by black households by the end of 1947. On January 15, 1948, arguments began for Shelley v. Kraemer in which the Supreme Court would consider the legality of restrictive covenants (The Court actually heard four cases together, with two of them originating in Washington’s Bloomingdale neighborhood). The high court eventually decided on May 3, 1948, that such covenants were unenforceable. This decision ensured that the African American community in Park View would continue to grow and thrive.

(Chart showing change in neighborhood demographics between 1943 and 1949 in the 400 blocks of Luray Place, Park Road, and Manor Place – the original area of Middaugh & Shannon’s Park View subdivision.)

(Chart showing change in neighborhood demographics between 1943 and 1949 in the 400 blocks of Luray Place, Park Road, and Manor Place – the original area of Middaugh & Shannon’s Park View subdivision.)

The increase in the number of black families in the Park View neighborhood during the 1940s also challenged the practice of segregating playgrounds, schools, and other institutions. Regarding the segregated Park View playground and the changing demographics of the neighborhood, noted attorney Charles H. Houston wrote in the Afro-American in 1947:

At Warder Street and Otis Pl., N.W., Washington is a large city playground with swings and other paly apparatus, surround by a high fence. Originally, under the segregated pattern of the District of Columbia, it had been set up and maintained as a playground for white children. But the neighborhood has changed, and the community is now predominantly colored.[1]

Houston’s editorial continues, noting that beginning in July 1947, black families on Newton Place, Warder Street, and Irving Street began a campaign with the Southern Conference for Human Welfare to integrate the Park View playground and concluding that if the playground were not opened to black children it would be necessary to take the Department of Recreation to court “and teach it a lesson in democracy.” While full integration did not occur until May 7, 1952, the use of the playground was change from one dedicated to white children to one meeting the needs of black children in July 1948 as the Board of Recreation recognized the significant shift in the neighborhoods population. The nearby Park View School followed suite and was changed from a white school to a black school in the fall of 1949.

Other notable changes in the community occurred in 1951 at the York Theater and Engine Company No 24. At the beginning of the year, Warner Bros. sold the York Theater to District Theaters which began management of the York on January 14, 1951. District Theaters by this time was one of the major theater circuits in the Mid-Atlantic area. District Theaters eventually operated a chain of 22 theaters, all of them catering to African American audiences. A.T. Swann – a native Washingtonian who attended Dunbar High School and Miner’s Teacher’s College, was hired to manage the York for District Theaters.

Similarly – and after much debate – the segregated District of Columbia Fire Department shifted to a policy of integration in October 1951 to address the issue of understaffed white companies. Engine Company No. 24, located at Rock Creek Church Road and Georgia Avenue, was among the first seven battalion headquarters which employed both white and black firemen. The integration of the firehouse was another reflection of the newly established African American community living in the surrounding neighborhood.

[1] Houston, Charles H. “The Highway,” Afro-American, October 4, 1947, p. 4.

[1] From “Mapping Segregation” [Website] available at: http://prologuedc.com/blog/mapping-segregation/ Viewed July 30,

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

Explore posts in the same categories: HistoryTags: neighborhood history, Park View

You can comment below, or link to this permanent URL from your own site.

October 5, 2015 at 2:40 am

0>>?my roomate’s sister makes $67 /hr on the computer . She has been unemployed for ten months but last month her paycheck was $21166 just working on the computer for a few hours.

find out here —- Click Here To Read More