One of Europe’s oldest currencies, the ruble has been in use since the 13th century. First made of silver, the currency derives its namesake from the Russian word ‘rubit’ which means to chop or hack, and originally was made from fragmented pieces of the Ukrainian hryvnia. The ruble has been chopped, hacked, collapsed, and re‐denominated many times throughout its 800 year history. The most volatile years came along with regime change and revolution.

In the 13th century, the Mongol Golden Horde took over Russia, beginning a period which has a tremendous influence on modern Russia and its culture. The sporadic invasion came as surprise to the powerful Rus’ state. One historian living at the time considered the invasion to be God’s punishment: “For our sins unknown nations arrived. No one knew their origin or whence they came, or what religion they practiced. That is known only to God, and perhaps to wise men learned in books”. During the time of the Mongol occupation, regular Mongol coins and imitations thereof were used in most of  Russia. Finally, Ivan’s son, Ivan Grozny completed the process by creating the Tsardom of Russia. During this time, wire money was used. Wire money was made of a silver wire that was pressed flat and struck with a massive die. The wire was then cut into equal-weighted pieces which became coins.

Russia. Finally, Ivan’s son, Ivan Grozny completed the process by creating the Tsardom of Russia. During this time, wire money was used. Wire money was made of a silver wire that was pressed flat and struck with a massive die. The wire was then cut into equal-weighted pieces which became coins.

The ruble was the Russian equivalent of the mark, a measurement of weight for silver and gold used in medieval Western Europe. The weight of one ruble was equal to the weight of one grivna. The first kopek coins, minted at Novgorod and Pskov about 1534 show a horseman with a spear, and doubtless the intention was to represent Ivan the Terrible, who was Grand Prince until 1547, and Tsar thereafter. Subsequent minting of the coin, starting in the 18th century, have instead Saint George striking down a serpent.

Since the monetary reform of 1534, one Russian accounting ruble became equivalent to 100 silver Novgorod coins or smaller 200 Muscovite denga coins. The coin with a rider on it soon became colloquially known as kopek. Ruble coins as such did not exist till Peter the Great, when in 1704 he reformed the old monetary system and ordered mintage of a 28-gramme silver ruble coin equivalent to 100 new copper kopek coins.

Since the monetary reform of 1534, one Russian accounting ruble became equivalent to 100 silver Novgorod coins or smaller 200 Muscovite denga coins. The coin with a rider on it soon became colloquially known as kopek. Ruble coins as such did not exist till Peter the Great, when in 1704 he reformed the old monetary system and ordered mintage of a 28-gramme silver ruble coin equivalent to 100 new copper kopek coins.

Ivan IV, “the Terrible” (1533-1584)

Ivan IV, popularly known as “Ivan the Terrible,” a strong and formidable ruler. The epithet “Terrible” is in fact a mistranslation from the Russian-language word “Groznyi” which in reality means “stern,” “formidable,” “feared by enemies.” Ivan’s long reign was marked by violent internal conflict and a series of wars against many foreign foes sparked by his desire to expand Muscovy’s frontiers, especially along and beyond the Volga river and to the Baltic seacoast in the west.

In 1534 a unified Russian monetary system made its first appearance, facilitated by the formation of a strong Russian state centered in Moscow. The currency reform was instituted by Elena Glinskaya, mother of Ivan IV. From the 14th century the minting technique of the silver coinage was metal was rolled into wire and sliced into equal sections of the proper weight. Little plates of slightly oval shape resulted. Relatively standard weight of the coins was achieved. The coins were struck by being placed between dies at which point the operator would hammer the upper die against the lower die. In 1704 the first Russian rubles were coined in Moscow. One hundred kopecks made a ruble.

Peter I, “the Great” (1689-1725)

Peter I, “the Great,” is a legendary figure in Russian and world history. Exuberant, bold, often reckless, Peter also pursued a policy of aggressive expansionism. He fought wars with Persians, the Ottoman Empire, and with Sweden. In these wars, he took over the Baltic states and the swamps that became St. Petersburg, a city which he named after himself. He also modernized Russia’s coinage. Peter the Great introduced the Rouble of 100 Kopeks [the first decimal currency], and his coins were some of the first milled coins in the world.

Peter I, “the Great,” is a legendary figure in Russian and world history. Exuberant, bold, often reckless, Peter also pursued a policy of aggressive expansionism. He fought wars with Persians, the Ottoman Empire, and with Sweden. In these wars, he took over the Baltic states and the swamps that became St. Petersburg, a city which he named after himself. He also modernized Russia’s coinage. Peter the Great introduced the Rouble of 100 Kopeks [the first decimal currency], and his coins were some of the first milled coins in the world.

He made St. Petersburg the capital of the Russian empire in 1721 during the successful Northern War against the Swedes. Among his many accomplishments, Peter irreversibly set into motion a process of intensive Westernization and modernization of Russia and established the Russian Empire as an important player in European and international politics. By the end of the 17th century Peter decided to initiate monetary reform by including the Ukrainian Hetmanate and the newly conquered Baltic provinces in the Russian monetary system. The monetary reform also simultaneously helped to finance the rearmament of the army, the creation of a navy, the building of canals and harbors, and the many large purchases made abroad to help achieve these goals.

The copper kopeck and the silver ruble [worth 100 kopecks] were taken as a basis of the new monetary system. In 1654 Alexei Mikhailovich, the father of Peter I, already attempted to replace the silver kopeck with a copper kopeck, but this had led to the so-called “copper revolt” in 1662. As a result, Peter prudently kept the silver kopeck in circulation next to the new copper kopeck for almost 20 years to let his subjects get used to the idea of copper money. The first silver ruble coin appeared in 1704.

In 1700 the first round coins were struck by machinery. Initially all the money production took place in Moscow in multiple mints. In 1724 the St. Petersburg mint started producing the new coins, the so-called “sun” rubles.

Peter II (1727-1730)

The thirteen year old Czar moved the capital back to Moscow in 1728. The St. Petersburg mint ceased production of coins until 1738 when Empress Anna restored St. Petersburg as the capital. Peter II declared himself of age, but took no part in affairs of the State, devoting himself exclusively to hunting.

Ivan VI (1740-1741)

The niece of the Empress Anna, Elizabeth [daughter of Peter I] seized power from Ivan, the two month-old son of Prince Anton Urlich of Brunswick and Anna Leopoldovna. Ivan IV lived on for some 23 years as a prisoner of the state until an unsuccessful rescue

attempt caused his jailers to kill him. A 1741 government decree directed the public to turn in the coins of Ivan VI within a year for an exchange of new coins at full value. The “ukaz” stipulated that anyone holding any coins of Ivan VI after June 1745 would be subject to punishment. Despite the decree, historians estimate that coins with the value of about 24,000 rubles were hoarded by the people and never turned in for exchange.

Peter III (1761-1762)

Elizabeth chose Carl Peter Ulrich, the son of her late sister Anna Petrovna, as her successor. Peter III’s first act upon accession was to make a humiliating peace with Frederick the Great of Prussia.

Peter III’s wife Catherine, with the help of the Orlov brothers [one of whom was Catherine’s paramour] and with the support of the Russian nobility, dethroned him. Soon afterwards the Orlovs murdered Peter III. During Peter’s short six-month reign, Count Peter Shuvalov’s scheme of raising money for the government, by reducing by half the metal content of the existing copper coinage, was quickly implemented. 150 million copper coins were over-struck [putting a new image with new denominations over the old coinage], doubling their value.

Catherine II (1762-1796)

Czar Peter III was forced to hand over the throne to Catherine, a German princess from the small principality of Anhalt-Zerbst. Her victorious wars against the Turks brought the Crimea and the Black Sea coast to Russia. She was the first to consult the population, at least in part, in the legislative commission of 1767. Catherine reorganized Russian local government and issued a charter of rights to the nobility. During her reign Enlightenment thought and culture reached their apogee in Russia, a process she personally encouraged. Her participation in the partitions of Poland brought most of the Ukraine, Belarus, and Lithuania into the Russian empire, ensuring Russia’s role as a major power. During Catherine’s reign, Siberia’s and the Urals’ copper mining industries were at their height. She decided to make coins out of copper rather than silver [because there was so much extra copper] which resulted in some pretty large coins, culminating in the massive the Rouble of Sestroretsk made out of 1 kg of copper!

Catherine had inherited Shuvalov’s plan to double the face value of the existing copper coinage and to reduce the fineness of the silver coinage. She firmly rejected the devaluation of the copper coinage and had Peter III’s already overstruck coppers overstruck again to restore them to their original value.

In 1768 the Assignation Bank opened in St. Petersburg and in Moscow . Several bank branches were established in other towns, called government towns. The emergence of Assignation rubles was due to large government spending on military needs, leading to a shortage of silver in the treasury, as all the calculations, especially in foreign trade, were conducted exclusively in silver and gold coins. The lack of silver, and huge masses of copper coins in the Russian domestic market meant that large payments were extremely difficult to implement consequently the introduction of bills for large transactions. The initial capital of the Assignation Bank was 1 million rubles copper coins – 500 thousand rubles each in St. Petersburg and in the Moscow offices; thus the total emission of banknotes was also limited to one million rubles.

branches were established in other towns, called government towns. The emergence of Assignation rubles was due to large government spending on military needs, leading to a shortage of silver in the treasury, as all the calculations, especially in foreign trade, were conducted exclusively in silver and gold coins. The lack of silver, and huge masses of copper coins in the Russian domestic market meant that large payments were extremely difficult to implement consequently the introduction of bills for large transactions. The initial capital of the Assignation Bank was 1 million rubles copper coins – 500 thousand rubles each in St. Petersburg and in the Moscow offices; thus the total emission of banknotes was also limited to one million rubles.

http://www.library.yale.edu/slavic/coins/catherine2.html

Alexander I (1801-1825)

Alexander led the successful coalition war against Napoleon, following the French invasion of Russia in 1812. He was the most enigmatic of Russia’s rulers. His charm and affability allowed him more easily to pursue often contradictory policies. His reforms, especially before 1811, strengthened legal order and the state while preserving autocracy. Yet he granted constitutions to Poland and Finland, and freed the serfs in the Baltic provinces. In his later years he turned toward mysticism and grew increasingly conservative.

Alexander I took a still more self-effacing stance than his father, Paul I, in coin design. He did away with Paul’s cruciform Imperial cipher theme and the religious device – “Not unto Us, Not unto Us, but in Thy name” – and opted for the Romanov double eagle and the rather bland inscription, “Russian Government Ruble Coin,” on the reverse side.

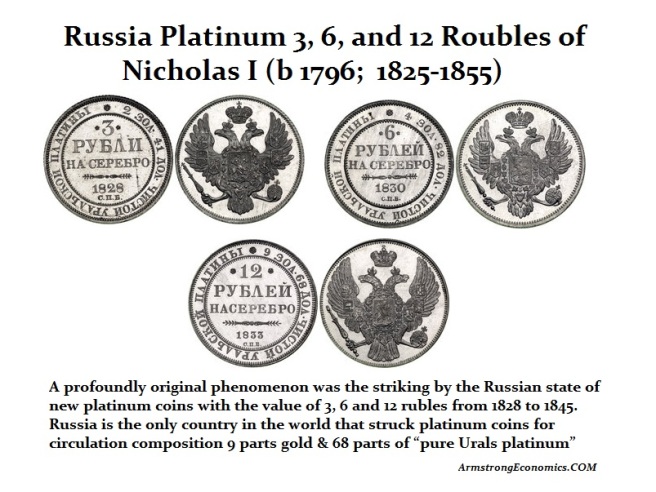

Nicholas I (1825-1855)

In 1822 Constantine, the second oldest brother of the childless Czar Alexander I, renounced his right to the Russian throne, and Alexander I designated his next oldest brother, Nikolai Pavlovich, as Czar. In December of 1825, hearing the news of Alexander’s death, the two brothers, Nicholas and Constantine, each independently swore allegiance to the other as the new Czar. In the prevailing confusion, partisans of a more liberal regime [the Decembrists], launched a poorly coordinated rebellion in favor of Constantine, who they thought would be more progressive. Nicholas was promptly installed as Czar and quickly suppressed the rebellion.

The thirty-year series of rubles and the eight-year series of 1 ½ ruble pieces of Nicholas I offer many interesting features. The regular coinage, which appears at first glance to be rather monotonous, reflects several new technological developments. The bilingual 1 ½ ruble/10 zloty coin (in Russian and Polish) is a numismatic reflection of Russia’s effort over the years to move towards a practical and more realistic consideration in Russo-Polish monetary and economic affairs. On the other hand, Nicholas I, a man of principle opposed to anything showy in his empire’s currency, paradoxically found himself sponsoring more commemorative coins than any previous Russian sovereign, achieving a record matched only be the last Czar, Nicholas II.

Alexander II (1855-1881)

Alexander II came to the throne better prepared than any other 19th century Russian emperor. He was a balanced, dutiful, hard-working man of essential goodwill. In 1861 he abolished the servitude of the Russian peasants in a decree that, although not wholly satisfying to either the nobles or the peasants, was probably the most statesmanlike possible at the time. Although at the beginning the peasants faced many difficulties in the new economic situation, within forty years they owned about 50% of Russian arable land – a better record than that of most countries that had instituted similar land reforms.

The Grand Duchy of Finland [the predecessor state of modern Finland] existed between 1809 and 1917 as an autonomous part of the Russian Empire and was ruled by the Russian Emperor as Grand Duke. Alexander II was the Emperor of Russia from 1855 until his assassination in 1881. He was also the King of Poland and the Grand Duke of Finland. In foreign policy, Alexander sold Alaska to the United States in 1867. Among his greatest domestic challenges was an uprising in Poland in 1863, to which he responded by stripping that land of its separate Constitution and incorporating it directly into Russia.

The decades of the 1860’s and 1870’s saw half a dozen foreign and private Russian efforts to take over part of the empire’s coinage system, with French, German and Belgian offers to produce nickel subsidiary coins. The Paris Mint struck a substantial quantity of subsidiary Russian coins in 1861, using hubs from St. Petersburg. Copper coinage was reorganized in 1867, and in 1876 the Ekaterinburg mint, which had been in operation for 150 years, was closed down. The St. Petersburg Mint took up the slack and expanded its production correspondingly. Saint Petersburg Mint remains one of the world’s largest mints founded in 1724 within the walls of Peter and Paul Fortress, it is one of the oldest industrial enterprises in Saint Petersburg now part of the Goznak State-owned corporation.

Alexander III (1881-1894)

The assassination of his father, Alexander II, in 1881 confirmed Alexander III in his conviction of the merit of firm, uncompromising leadership, the need to suppress sedition and to check any tendencies which might prejudice the Czar’s position. He was unsympathetic to and largely uncomprehending of the intellectual and social ferment among his subjects.

During the first five years of his reign Alexander III retained the regular ruble type which had not changed since 1860. For the coronation ceremonies in 1883 it was decided to issue a special coronation ruble which would take the place of the traditional lesser coronation medals. In 1885 the Mint’s operating structure as well as the entire Russian monetary system was extensively revised. A new portrait type for gold and large silver coins was introduced.

Nicholas II (1894-1917)

Nicholas II probably would have been a relatively good ruler in more auspicious and tranquil times. The Empire moved to the gold standard in 1897, with no major changes in silver coinage. The heavy burden on the St. Petersburg Mint of striking a vast quantity of the new gold coins led to the decision to farm out to the Paris and Brussels Mints the minting part of the banks silver coinage from 1896 to 1899. The Russians provided the French and the Belgians with hubs or dies for the coinage they produced, so that one can distinguish the foreign-minted coinage by looking at the edge of the coin: a single star for Paris and two stars for Brussels. The last rubles of the Imperial era were struck by Nicholas II in 1915 and subsidiary coinage continued until 1917.

Nicholas II was the last Emperor of Russia, Grand Duke of Finland, and titular King of Poland. His reign saw Imperial Russia go from being one of the foremost great powers of the world to economic and military collapse. Under his rule, Russia was decisively defeated in the Russo-Japanese War. The Anglo-Russian Entente, designed to counter German attempts to gain influence in the Middle East, ended the Great Game between Russia and the United Kingdom. As head of state, Nicholas approved the Russian mobilization of August 1914, which marked the beginning of Russia’s involvement in the First World War, a war in which 3.3 million Russians were killed. Nicholas II abdicated following the February Revolution of 1917 during which he and his family were imprisoned and executed in 1918.

Nicholas II was the last Emperor of Russia, Grand Duke of Finland, and titular King of Poland. His reign saw Imperial Russia go from being one of the foremost great powers of the world to economic and military collapse. Under his rule, Russia was decisively defeated in the Russo-Japanese War. The Anglo-Russian Entente, designed to counter German attempts to gain influence in the Middle East, ended the Great Game between Russia and the United Kingdom. As head of state, Nicholas approved the Russian mobilization of August 1914, which marked the beginning of Russia’s involvement in the First World War, a war in which 3.3 million Russians were killed. Nicholas II abdicated following the February Revolution of 1917 during which he and his family were imprisoned and executed in 1918.

Copied from https://en.numista.com/forum/topic44228.html

Nicholas II opposed all democratic reforms and wished for the Russian government to remain an absolute monarchy. He also pursued extremely anti-Semitic legislation (which led to the foundation of the Jewish Labor Bund), as well as anti-labor laws. His subjects, however, had different ideas. This led to the famous Revolution of 1905, which was really a wave of revolutions across Russia, each targeting a specific problem. Tsar Nicholas II responded with violence, but this didn’t stop the revolts.

Finally, he was forced to enact massive reforms, one of which included creating the democratically-elected Imperatorski Duma. He also granted the freedom of speech and assembly. He also fought two wars, the Russo-Japanese War (which he lost) and WWI (which he one but at a heavy cost to the nation). In addition, the Russian government began to print millions of roubles in banknotes without minting coins to back them up with, which caused inflation and a food shortage. All these events set the stage for the Russian Revolution.

The Russian Revolution was in fact a series of related primarily Socialist rebellions and wars. The first of these, the February Revolution, broke out in the streets of Petrograd . The February Revolution deposed the Tsar and created the Russian Provisional Government, which was partially democratic, as well as the Petrograd Soviet, an influential legislative body. The Russian Provisional Government eventually ordered the execution of the Tsar and his entire family. Unfortunately for the Soviet, the Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, took down the Provisional Government in the October Revolution. Lenin and his followers established the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR). The RSFSR was the world’s first socialist state, which completely overhauled the government and the economy to comply with socialist models. The RSFSR also produced coins in 1921, the first since the fall of the Tsarist government.

Finally, the Soviet Union was established as a union of the formerly independent RSFSR, Ukrainian Socialist Soviet Republic, the Byelorussian Socialist Soviet Republic, and the Transcaucasian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic [a federation of Georgia, Azerbaijan and Armenia]. RSFSR coinage continued for a few years and then the Soviet Union issued distinctive coins, including a pictorial 50 Kopeks and 1 Rouble.

A medal showing both sides, struck by Catherine the Great in 1780. The first piece depicts the Empress and the second piece has the inscription in Latin, “Mare Liberum” – which means “Free Seas”. This refers to Catherine’s Declaration of Armed Neutrality of February 28, 1780, the goal of which was to preserve the struggling but ever-increasing Russian commerce on the high seas from the depredations of the warring British, Spanish, French and American navies during the American Revolutionary War.

http://www.library.yale.edu/slavic/coins/papercurrency.html

The Soviet Union.

After the 1917 Bolshevik revolution, the ruble lost one third of its value, and in the following years while the country was gripped by civil war, the ruble dropped from 31 against the dollar to nearly 1,400. The ruble hit its historic low of 2.4 million per USD after the civil war and the year the revolution’s leader Vladimir Lenin died. It was re‐denominated to 2.22. Throughout the Soviet Union, the ruble was little used outside state borders, so the government kept the official rate close to the dollar, a massive overvaluation. In the last years of the Soviet Union, the economic crisis caused panic among the population who were ‘stuck’ with their increasingly worthless rubles. A black market naturally developed, and while the official rate for the ruble was 0.56 per dollar, a single greenback actually sold for 30‐33 rubles on the street.

The Soviet currency had its own name in all Soviet languages, sometimes quite different from its Russian designation. All banknotes had the currency name and their nominal printed in the languages of every Soviet Republic. This naming is preserved in modern Russia; e.g.: Tatar for ruble and kopek are sum and tien. The current names of several currencies of Central Asia are simply the local names of the ruble. Finnish last appeared on 1947 banknotes since the Finnish SSR was dissolved in 1956.

The first coinage after the Russian civil war was minted in 1921-1923 with silver coins in denominations of 10, 15, 20 and 50 kopecks and 1 ruble. Gold chervonets were issued in 1923. These coins bore the emblem and legends of the RSFSR [Russian Federated Soviet Socialist Republic] and depicted the famous slogan, “Workers of the world, Unite!”. The 10, 15, and 20 kopecks were minted with a purity of 50% silver while the ruble and half ruble were minted with a purity of 90% silver. The chervonetz was 90% gold. These coins would continue to circulate after the RSFSR was consolidated into the USSR with other soviet republics until the discontinuation of silver coinage in 1931. After Joseph Stalin’s consolidation of power following the death of Lenin, he launched a third redenomination in 1924 by introducing the “gold” ruble at a value of 50,000 rubles of the previous issue. This reform also saw the ruble linked to the chervonets, at a value of 10 rubles and put an end to chronic inflation. Coins began to be issued again in 1924, while paper money was issued in rubles for values below 10 rubles and in chervonets for higher denominations.

In August 1941, the wartime emergency prompted the minting facilities to be evacuated from Moscow and relocated to Permskaya Oblast as German forces continued to advance Eastward. It only became possible to resume coin production in the autumn of 1942, for one year the country was using coins made before the war. Furthermore, the coins were made of what had suddenly become precious metals – copper and nickel, which were needed for the defense industry. This meant many coins were being produced in only limited quantities, with some denominations being skipped altogether until the crisis finally abated in late 1944. These disruptions led to severe coin shortages in many regions. Limits were put in place on how much change could be carried in coins with limits of 3 rubles for individuals and 10 rubles for vendors to prevent hoarding as coins became increasingly high in demand. Only high inflation and wartime rationing helped ease pressure significantly. In some instances, postage stamps and coupons were being used in the place of small denomination coins. It was not until 1947 that there were finally enough coins in circulation to meet economic demand and the restrictions could be eased.

In August 1941, the wartime emergency prompted the minting facilities to be evacuated from Moscow and relocated to Permskaya Oblast as German forces continued to advance Eastward. It only became possible to resume coin production in the autumn of 1942, for one year the country was using coins made before the war. Furthermore, the coins were made of what had suddenly become precious metals – copper and nickel, which were needed for the defense industry. This meant many coins were being produced in only limited quantities, with some denominations being skipped altogether until the crisis finally abated in late 1944. These disruptions led to severe coin shortages in many regions. Limits were put in place on how much change could be carried in coins with limits of 3 rubles for individuals and 10 rubles for vendors to prevent hoarding as coins became increasingly high in demand. Only high inflation and wartime rationing helped ease pressure significantly. In some instances, postage stamps and coupons were being used in the place of small denomination coins. It was not until 1947 that there were finally enough coins in circulation to meet economic demand and the restrictions could be eased.

Commemorative coins of the Soviet Union: [images]

In 1965, the first circulation commemorative ruble coin was released celebrating the 20th anniversary of the Soviet Union’s victory over Germany, during this year the first uncirculated mint coin sets were also released and restrictions on coin collecting were eased. In 1967, a commemorative series of 10, 15, 20, 50 kopecks, and 1 ruble coins was released, celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Russian Revolution and depicted Lenin .

Starting in 1991 with the final year of the 1961 coin series, both kopeck and ruble coins began depicting the mint marks (M) for Moscow, and (Л) for Leningrad. In late 1991, a new coinage was introduced in brass-plated steel, and cupro-nickel The 10 rubles was bimetallic with an aluminium-bronze centre and a cupro-nickel-zinc ring. The series depicts an image of the Kremlin on the obverse rather than the soviet state emblem. However, this coin series was extremely short lived as the Soviet Union ceased to exist only months after its release. It did however, continue to be used in several former soviet republics including Russia and particularly Tajikistan for a short time after the union had ceased to exist out of necessity.

From Soviet to Shock Therapy

During the Khrushchev and Brezhnev eras, the USSR and USA fought proxy wars, namely the Korean, Vietnam, and Soviet-Afghanistan wars. Although they left a big impact on history, they had no impact on Soviet coinage. The Soviet Union also maintained control over its Eastern European puppet states.

In 1985, Mikhail Gorbachev was selected as leader of the Soviet Union. He engaged in talks with America, established more political [Peristroika] and personal [Glasnost – the reduction of censorship] freedoms, and slowly began the process of dismantling the socialist economy. Between 1989 and 1991, the Soviet Union began the process of collapse. Each of the 15 republics declared Independence, and finally, the RSFSR did so as well under the leadership of Boris Yeltsin. The Soviet Union came to an end in 1991. Gosbank, the State Bank of the USSR issued a set of coins in 1991, and the independent Russian Federation issued its own coins starting in 1991. Eventually, all the former Soviet republics issued coins.

The ruble collapsed along with the Soviet state, and different currencies were set up in the 15 different republics. The Central Bank of Russia replaced the State Bank of the USSR [Gosbank] on January 1, 1992 and the Russian ruble replaced the Soviet ruble.

The break-up of the Soviet Union was not accompanied by any formal changes in monetary arrangements. The Central Bank of Russia continued to ship USSR ruble notes and coins to the central banks of the fourteen newly independent countries, which had formerly been the main branches of Gosbank in the republics. During the first half of 1992, a monetary union with 15 independent states all using the ruble existed. Since it was clear that the situation would not last, each of them was using its position as “free-riders” to issue huge amounts of money in the form of credit [since Russia held the monopoly on printing banknotes and coins]. The Russian central bank responded in July 1992 by setting up restrictions to the flow of credit between Russia and other states. The final collapse of the ruble zone began with the exchange of banknotes by the Central bank of Russia on Russian territory at the end of July 1993. As a result, other countries still in the ruble zone were “pushed out”. By November 1993 all newly independent states had introduced their own currencies, with the exception of war-torn Tajikistan (May 1995) and unrecognized Transnistria (1994).

The new Russian Central Bank set the official exchange rate at 125 rubles to the US dollar. By December 1992, the ruble had already lost about two third’s of its value. Russia’s post‐Soviet economy was dominated by ‘shock therapy’, and as President Boris Yeltsin’s reforms spurred rapid inflation, millions of Russians lost their savings. Boris Yelstin’s political infighting with the Communists in 1993 caused the ruble to slide more, down to 1,247 per 1 USD. Yeltsin won the political coup, and a constitution was signed on December 12, 1993. Shortly after the political victory, in January 1994, the authorities banned the use of the US dollar and other foreign currencies in circulation in an attempt to stymie the ruble’s decline.

Black Tuesday and Black Thursday

On October 11, 1994, an event known as ‘Black Tuesday’ hit the Russian financial market, and the ruble collapsed 27 percent in one day, which on top of a decline in GDP and massive inflation, catapulted Russia into an economic recession. By the end of 1995, chronic inflation had reached 200 percent. In 1996 the currency closed at 5,560 rubles per US dollar. 1997 was the first year of relative stability, but the ruble still fell to 5960 rubles per dollar. An era of stability prompted the government to devalue the currency and slash 3 decimal places, and on January 1, 1998, the ruble was set to 5.96 against the US dollar.

On August 17, 1998, Russia announced a technical default on its $40 billion in domestic debt and ceased to support the ruble on the same day. At the time, the bank only had $24 billion in reserves. The stock market and ruble both lost more than 70 percent, and nearly a third of the country’s population fell below the poverty line. Along with the default came another mass devaluation of the ruble. In six months it fell from 6 to the dollar to 21 to the dollar.

On May 27, 1998, the Central Bank increased the main lending rate to 150 percent, which brought loans to a near halt. By the end of 1998, inflation was 84 percent and the Russia GDP lost 4.9 percent. Both currency crises in the 90s forced the governors of the Central Bank to resign. The 1998 ruble crisis, like today, was driven by falling oil prices, which went as low as $18 in August 1998. However, today’s crisis is much less of a risk, as Russia has more than 10x the amount of currency reserves as it did in 1998.

The ruble met the new millennium with a rate of 28 to the dollar, and after hitting a low of 31 in 2003, started to slowly strengthen. In 2008, Russia along with the much of the rest of the world fell into recession, losing 7.8 percent of GDP in 2009. The Russian economy fared the crisis rather well, and the economy was back on track with 4.5 percent growth in 2010.

Russia is facing its biggest currency crisis since 1998. The ruble has mostly been tumbling in tandem with weak oil prices, which have nearly halved since June, when Brent crude sold for $115 a barrel. In January, prices plummeted below $50 a barrel. The ruble has lost more than half its value and investors worry that the devaluation, along with falling oil and political tensions, would send Russia into recession again. The Central Bank forecast a 4.7 percent decline in GDP if oil prices stay at $60 per barrel. On December 15 the ruble plunged 11 percent, and the Central Bank increased the key lending interest rate to 17 percent, in the middle of the night. Russia’s biggest oil producers, including Gazprom and Rosneft, have been ordered to sell a fraction of their foreign exchange revenues over the next couple of months in order to support the ruble, adding an estimated $1 billion to the daily market.