by Maddy Costa

Although there are some 150,000 words in English with roots in Greek, the two languages didn’t meet directly – according to wikipedia – until modern times. So the connection was often made via an intermediary, and usually that was Latin. For instance, ‘butter’ comes from Old English butere from Latin butyrum from Greek βούτυρον.

Or, in another example, our word physics, from Latin physica, begins with τὰ φυσικά.

English made strategic borrowings from Greek, for instance creating the word ‘telephone’ by fusing τῆλε referring to something far away and φωνή referring to voice.

And there are instances of Greek reaching English via Arabic scientific and philosophical writing, for instance alchemy, from χημεία.

Alchemy could be described as a process of translation.

I grew up in a bilingual household. My parents were both born in Cyprus but came here as children, met as teenagers, married and made me a year later. My mother was five when she arrived in a flurry of snow and – despite the weather – assimilated quickly. My father was nine and struggled, particularly with learning English. He didn’t want me or my brother to experience the same struggle, so no concerted effort was made to teach us Greek when we were small. When we were enrolled in Greek school, I refused to go: I wanted to go to Brownies, or watch TV, not submit to more lessons on a Saturday. I hate 10-year-old me.

I grew up listening to Greek but never actually speaking it. At school I learned French and the two languages muddled in my head until I went to university to study English literature and gradually both slipped away. Now the thing I’m most confident saying in Greek is συγγνώμη, δεν καταλάβω. I’m sorry, I don’t understand.

From the Greek word for three, τρία, we get triangles. From πέντε, pentagons, and οκτώ, octagons.

Γλώσσα, tongue, but also language, gives us glossaries; βιβλίο, book, bibliographies.

From the Greek words for stranger, ξένος, and φοβία, fear, we get xenophobia.

Μισώ, hate, and γυναίκα, woman, give us misogyny.

While φίλος, friend, and άνθρωπος, man, make philanthropy.

And oh the joy of discovering that hoi polloi comes from “the many”: η πολοί.

My paternal grandparents never learned to speak English: my mother has acted as intermediary in all my communication with them. Once, before my grandfather died, I arrived at their council flat before my parents and didn’t know what to say. I could have asked what brought them to England. How they travelled here, what they thought when immigrations officials decided that their surname would be Costa because that was easier to handle than the full patronymic. How quickly they settled, whether they missed Cyprus and wanted to go home. But I didn’t know how to say any of those things. So we sat in loving silence sharing a bowl of fresh almonds, cracking their shells one by one. I didn’t even like almonds at the time. I knew the words for that – δεν μου αρέσει – but could never have hurt my grandparents’ feelings by saying them.

I was born in London and grew up in Hackney, a borough described by journalist Paul Harrison in his 1982 book Inside the Inner City as “a sump for the disadvantaged of every kind … a chaotic mixture of races and classes where whites, West Indians, Asians, Africans and Cypriots are shuffled like the suits in a pack of cards”. I like that he doesn’t specify whether he means Greek or Turkish Cypriots. I grew up in a bilingual household in a polyphonic – πολοί, many, φωνή, voice – borough in a city that housed people from across the globe. Indoors, on city streets, I have always been surrounded by languages I don’t understand.

The first time I visited Paris, I noticed that on the metro pretty much everyone spoke French. I mean, fine, it’s France. But how strange the lack of variety. The singularity of tongue.

When my auntie met her Greek husband, she could make him laugh simply by using Cypriot words for common things. All she had to do was call his socks κλάτες instead of κάλτσες and she’d set him off again.

Cypriot, it turns out, is quite different from modern Greek – according to wiki again, closer to Byzantine Medieval Greek. My mother once almost offended a man at a περίπτερο by asking for a bottle of water using the Cypriot for bottle.

Because the island has always been inhabited by Muslims as well as Christians, Arabic sayings are also common among Greek Cypriots. We share the phrase Masha’Allah, an expression of thanks to god, as though our beliefs are not divisive. Which they wouldn’t be. In a different world.

One of the questions in Race Cards, Selina Thompson’s excoriating survey of living in a society characterised by institutionalised racism, asks: do you see colour? Responding to the work at the Fierce festival in 2015, I wrote: yes – when I travel outside London, and find myself in places where people are predominantly white.

I knew before the EU referendum how different the corner of England I grew up in was and is from the rest of the country. As the years have passed, London has only become more polyglot – remember these? πολοί, many, γλώσσα, language – as its population has risen by one and two million. I can travel the globe just by walking to Stockwell station and getting on the Victoria line. It remains a feeling of incredible comfort, this cacophony of incomprehensible chatter: like Christmas with my extended family.

Every so often someone Greek will come within hearing and I’ll smile in recognition – καταλάβω κάτι! Or rather, it’s not that I understand exactly, but I know the shape of the words, the texture of them. I know where they’re from.

It’s happened more and more since Greece’s economic collapse and its acceptance of an EU austerity plan despite the slim-majority όχι vote at referendum. Usually the people I hear are relatively young, middle-class, seem comfortably off. Economic migrants, you could call them.

If the words didn’t feel so offensive.

Visiting my aunties over Easter I learned that the Greek translation of “and they lived happily ever after” is και έζησαν αυτοί καλά και εμείς καλύτερα – they lived well and we lived better.

The etymology of the word cynic lies in an apocryphal story of the Greek philosopher Antisthenes, a pupil of Socrates, whose followers were dubbed dog-like. Dog is another of those words where Greek and Cypriot diverge: my family pronounce it shilos, contrary to the hard kappa in the middle of σκύλος. Although this might seem counter-intuitive, it’s the even more emphatic kappa at the beginning of κύων, an alternative spelling for dog, that gives us cynic, κυνικός.

It turns out that the Greek word I’ve been using for understand might in fact be Cypriot. Either that, or I’m just getting it wrong. Really I should be saying καταλαβαίνω. It’s only a small thing. But it’s these minor embarrassments that keep me silent, too anxious to speak.

More and more, I don’t know where people are coming from.

Politically, I mean.

Politics comes from πολιτική, the word used by Aristotle as the title of a book on governing and governments.

A couple of years ago I started to wonder whether the ancient Greek notion of Δημοκρατία – the classic white-supremacist-patriarchal notion of democracy in which only adult male citizens, not women, not slaves, were allowed to vote – could be to blame for every bad thing that has happened in the past 2000 years.

Whether the Greeks didn’t just give us the words for xenophobia and misogyny but their physical manifestations, too.

The Greek word for father is πατέρας, while the chief head of a family was called the πατριάρχης. They gave Latin the words for both father, pater, and patriarch, patriarchae. From which English gets the word patriarchy.

What if ancient Greek civilisation were a base metal, which has proven impossible to transmute into gold?

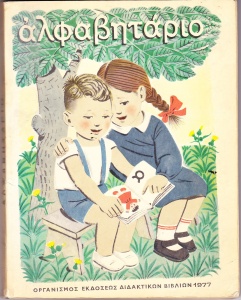

From the first two letters of Greek, άλφα and βήτα, English made alphabet.

I understand the words. I know their roots. But at the same time