Author’s note: This is the sixth installment in a series about the Eight Views of Omi. (Read part five here)

Please enjoy and follow along as we deconstruct the modern-day landscape of Shiga and examine its vibrant history and culture. Thank you for reading! – Maddie

著者メモ: 近江八景にかかるシリーズの第六稿です。(第五稿はここです)

現代の滋賀県の景色を解体したり、豊かな歴史と文化を調べたりしているので、楽しんで読み進めてください!ご読了ありがとうございます。 – マディ

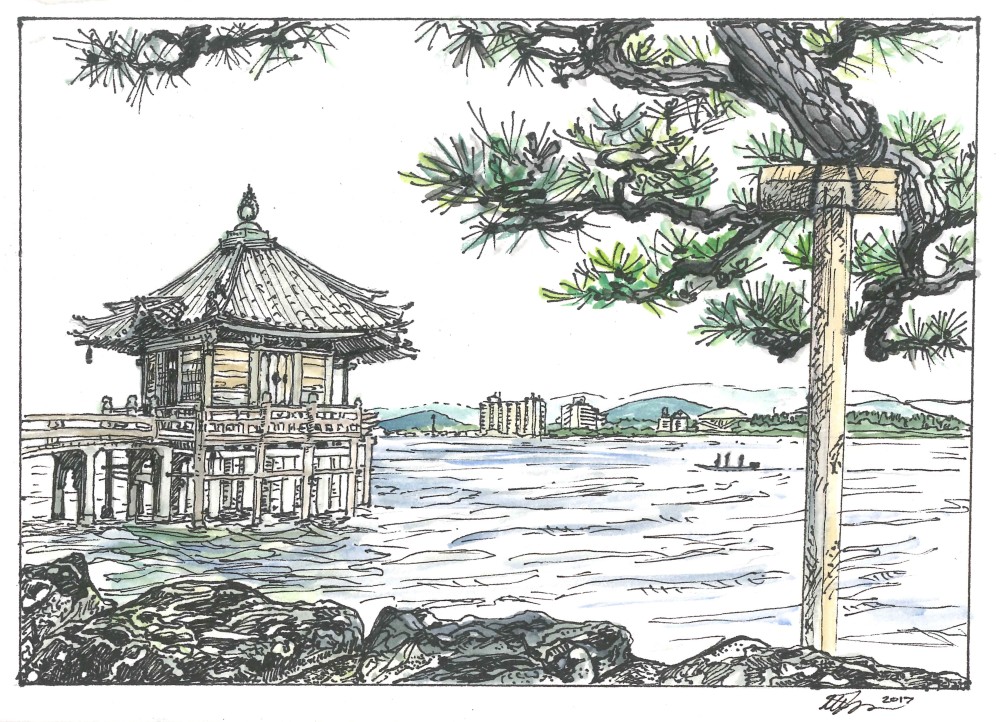

About a thirty minute walk from the bustle of Katata Station stands Mangetsuji, the Temple of the Full Moon. Situated on the shore at the narrowest part of Lake Biwa, the silence of its temple grounds feels a world away from most of industrial Shiga. Old pine trees, their branches held up by wooden braces, stretch out over the water. A beautiful wooden building rises out of the water on stilts, connected to the shore by a wooden bridge. This is Ukimido, the Floating Pavilion.

堅田駅のにぎやかさから約30分ほど歩くと、満月寺があります。琵琶湖の最狭部に立ち、境内の静寂は多くの産業的な滋賀県と別の世界みたいです。木造の支柱で枝が支えられた古い松は水の上に伸びています。美しい木造建物は湖面の上に建ち、木造の橋で岸につながっています。これは浮御堂と言われています。

Mangetsuji was quiet when I arrived one Friday morning, and the day was already hot. I stopped by the temple office to pay my 300 yen entrance fee, taking the opportunity to confirm with the woman working there that I was allowed to sketch and paint within the temple grounds. (Many temples in Kyoto and Nara prohibit sketching and painting, maybe because of crowds). After I assured her that my paints were not the type that would make a mess, she said it was perfectly fine.

ある金曜日の朝に着いたら、満月寺は静かでした。そして、その日はもう暑かったです。300円の入院料を払うためにお寺の受付に寄り、その時に境内でスケッチしたり色塗りしたりするのは大丈夫かどうか女性職員に確認しました。(おそらく人が多いため、京都と奈良で多くのお寺はスケッチ禁止です。)私が持ってきた絵具は汚すタイプではないと説明すると、彼女は全然大丈夫だと答えてくれました。

Before I sat down to draw, I decided to pay my respects to the pavilion itself. Halfway across the bridge, my stomach dropped as I was hit by a fierce wind. The main grounds of the temple had been completely protected, but out on the bridge I felt the full force of the continuous wind blowing south across Lake Biwa. I changed into the slippers provided in front of the pavilion, careful not to lose my balance and fall off into the water. The temple and bridge were much taller than I had anticipated, and I was surprised by how exposed and frail I felt. I was at the mercy of the wind and water, relying on the sturdiness of the old structure.

絵を描くのに腰を下ろす前に、浮御堂そのものに敬意を表することにしました。橋を半分渡ったところで、激しい風に煽られてドキッとしました。本殿は完全に守られていましたが、橋の上では琵琶湖を南に吹き抜ける風の力を感じました。浮御堂の前に置かれていたスリッパに履き替えて、バランスを崩して水に落ちないように気を付けました。浮御堂とこの橋は意外と高いし、かなりむき出しの状態で、その脆さに驚きました。古い建物の頑丈さを頼りに、風と水のなすがままにいました。

Ukimido was originally built around 995 AD by a Tendai scholar named Genshin (also known as Eshin Sozu). According to legend, Genshin, looking out at night over Lake Biwa from Hieizan Enryakuji Temple, noticed a brilliant light in the water. When he went to investigate, he discovered a 54mm gold statue of Amitabha, a celestial Buddha in Mahayana Buddhism. As a memorial service to the fishes who were killed when he pulled up the statue with his net, he built another statue of Amitabha. Inside it, he placed the gold statue he had found. Genshin then proceeded to carve another one thousand small statues of Amitabha and to build Ukimido. The statues of Amitabha still stand inside the pavilion today.

元々浮御堂は、長徳年間(西暦995年頃)に源信(恵心)と言われる天台宗の僧都に建てられました。伝説により、源信は、夜に比叡山延暦寺から琵琶湖を見た時、水中にさんさんと輝いている光に気づきました。確かめに行ったら、大乗仏教の如来の一つである阿弥陀如来の54mmの金製の像を見つけました。網で取り出した時に殺された魚の供養として、も一つの阿弥陀如来の像を作りました。その中に、見つけた金の像を置きました。それから源信は、他の一千体の小さな阿弥陀仏を彫って、浮御堂を作りました。阿弥陀仏の「千体閣」は今日も浮御堂の中に立っています。

Ukimido did fall into ruin at some point in time, but it was restored using a Noh Stage from the Imperial Court, gifted to the temple by Emperor Sakuramachi (1720-1750). Most recently, it was destroyed by the devastating 1934 Muroto Typhoon, but was rebuilt in its current form in 1937.

浮御堂は廃れた時もありましたが、宮中の能舞台を使って修復されました。その能舞台は、桜町天皇(1720-1750)によって与えられました。近世では、破壊的な1934年の室戸台風に壊されましたが、1937年に現代の形に再建されました。

Not surprisingly, Ukimido is featured in many works of art. In the Eight Views of Omi series, it appears in a scene showing late autumn on the lake, with a flock of wild geese returning home. Hokusai’s version shows the pavilion backed by the warm reds and purples of sunset. Nearly every iteration includes fishermen, and – by sheer luck – mine is no exception. A fishing boat carrying three people floated around the lake as I painted. In the print by Harunobu, a similar boat and arrangement of people can be seen, but they are operating their boat by paddle rather than motor.

当然のことながら、浮御堂は多くの作品の題材となっています。近江八景では、帰り道の野生のガンの群れとびわ湖の晩秋を描いた風景に中に描かれています。北斎のバージョンでは、日没の暖かい赤色と紫色を背景として浮御堂が描かれています。ほとんど全部の画に漁民が描かれていて、私のも(偶然ですが)例外ではないです。描いているとき、3人の人を運ぶ漁船が湖に浮かんでいました。春信の版画では、似ている船と人の姿が見られますが、モーターではなくむしろ櫂で船を操縦しています。

Katata has changed and grown into a modern city, but the view of Ukimido still feels remarkably peaceful and nostalgic. With the exception of a few scattered apartment complexes and love hotels visible on the far shore of the lake, and the Biwako Ohashi Bridge in the distance (obscured in my painting by the pavilion’s walkway), I wonder if it couldn’t pass as a scene from the 19th century.

堅田は変わってきて現代的な都市に発展しましたが、浮御堂の景色ではまだとても静かで懐かしい感じがします。向こうの湖畔に点在して見えるアパートやラブホテル、そして遥か遠くの(私の絵では浮御堂の橋に隠れている)琵琶湖大橋以外、19世紀の景色に見間違えられるのではないかと思います。

One of the most famous artists to visit Ukimido was the haiku poet Matsuo Bassho (1644-1694). Bassho, who spent his life wandering Japan and composing poems, wrote this collection in Katata:

浮御堂を訪れたもっとも有名な芸術家の一人は松尾芭蕉(1644-1694)という俳人です。日本を放浪しながら俳句を詠んでいた芭蕉は堅田でこの連句を書きました:

“Open the lock

let the moon shine in -

Floating Temple

How easily it rose

And now it hesitates,

The moon in clouds

Sixteenth night moon -

In the night’s darkness.”

錠あけて 月さし入れよ 浮御堂

やすやすと 出でていざよふ 月の雲

十六夜や 海老煮るほどの 宵の闇

To me, his haikus add a rawness, or sense of ordinary life, to Ukimido. I wonder where he sat when he wrote it. I can’t imagine one boiling shrimp in the temple, but perhaps from a nearby house he looked out over the water and saw the bright moon and dark outline of the floating temple. His writing also conveys – to me – some sense of the same frailness that I felt when I walked out to the temple. Even the confident, shining moon now hides behind the clouds, and this humble description of boiling shrimp in the dark reminds me of how I imagined the ukiyo-e painters shivering in the wind as they sketched the snow-covered Hira Mountains. The effort behind each beautiful piece, be it poem, print, or hand-built pavilion, is what truly carries and conveys everyday life and the human experience across time.

自分にとって、芭蕉の連句は生々しさ、もしくは日常の生活感を浮御堂に付け加えます。詠んだ時にどこに座っていたのかなと思っています。浮御堂の中で海老を煮るのは想像できませんが、近くの宿から湖に目をやり、明るい月と浮御堂の黒い輪郭を見かけたかもしれないです。芭蕉の俳句は、私にとって、浮御堂の橋を渡った時に感じたもろさも伝えています。自信満々に輝く月でも雲の後ろに隠れています。そして、闇の中で海老を煮るといったつつましい描写で、真っ白の比良山麓を描きながら風に震えている浮世絵師に思いを馳せました。俳句・版画・手作りの浮御堂であろうと、それぞれの美しい作品の背景にある努力が、時代を超えて日常生活と人間の経験を本当に運んだり伝えたりしているのだ。