When the war came in August, Teilhard returned to Paris to help Boule store museum pieces, to assist cousin Marguerite turn the girl’s school she headed into a hospital, and to prepare for his own eventual induction. Teilhard’s induction was delayed, and his Jesuit Superiors decided to send him back to Hastings for his tertianship, the year before final vows. At Hastings, Teilhard made the “long retreat” or the 30-day silent retreat focused on the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius of Loyola that is a central component of Jesuit training. Undoubtedly, this experience of solitude and spiritual direction was a defining moment on forming Teilhard’s personal relationship with God.

Teilhard is sometimes criticized as being insensitive to suffering and death, both in his theology and his personal correspondence. This criticism is misplaced. Teilhard both witnessed and knew first-hand immense physical and personal suffering, from having six of his siblings die prematurely, to witnessing the carnage of the trenches in World War I to being prohibited from publishing his life’s work of synthesizing traditional Catholic theology with evolutionary biology. Despite this immense personal suffering, he maintained an optimism and healthy perspective that others attribute to insensitivity. Although I did not know Teilhard, I attribute his optimism to a deep relationship with God, tattooed in his spirit by the 30 long retreat. After that experiences, Teilhard was able to view all suffering in light of the ultimate purpose of growing closer to the Cosmic Christ. Teilhard viewed suffering as a potential to accelerate the Kingdom of God:

What a vast ocean of human suffering spreads over the entire earth at every moment! Of what is this mass formed? Of blackness, gaps, and rejections. No, let me repeat, of potential energy. In suffering, the ascending force of the world is concealed in a very intense form. The whole question is how to liberate it and give it a consciousness of its significance and potentialities.

The world would leap high toward God if all the sick together were to turn their pain into a common desire that the kingdom of God should come to rapid fruition through the conquest and organization of the earth. All the sufferers of the earth joining their sufferings so that the world’s pain might become a great and unique act of consciousness, elevation, and union. Would not this be one of the highest forms that the mysterious work of creation could take in our sight?

Could it not be precisely for this that the creation was completed in Christian eyes by the Passion of Jesus? We are perhaps in danger of seeing on the cross only an individual suffering, a single act of expiation. The creative power of that death escapes us. Let us take a broader glance, and we shall see that the cross is the symbol and place of an action whose intensity is beyond expression. Even from the earthly point of view, the crucified Jesus, fully understood, is not rejected or conquered. It is on the contrary he who bears the weight and draws ever higher toward God the universal march of progress. Let us act like him, in order to be in our existence united with him. (“The Significance and Positive Value of Suffering,” quoted in Human Energy, HarperCollins)

The suffering Teilhard described was not an abstract suffering. Unfortunately, the carnage of World War I would soon hit the Teilhard de Chardin family. Two months after Teilhard completed his 30 day Long Retreat, Teilhard learned that his younger brother Gonzague had been killed in battle near Soissons.

Shortly after this Teilhard received orders to report for duty in a newly forming regiment from Auvergne. After visiting his parents and his invalid sister Guiguite at Sarcenat, he began his assignment as a stretcher bearer with the North African Zouaves in January 1915. At his request he was sent to the front and also became chaplain. Teilhard carried the Blessed Sacrament wherever he went, and celebrated Mass in a variety of suboptimal circumstances.

The powerful impact of the war on Teilhard is recorded in his letters to his cousin, Marguerite, now collected in The Making of a Mind. They give us an intimate picture of Teilhard’s initial enthusiasm as a “soldier-priest,” his humility in bearing a stretcher while others bore arms, his exhaustion after the brutal battles at Ypres and Verdun, his heroism in rescuing his comrades of the Fourth Mixed Regiment, and his unfolding mystical vision centered on seeing the world evolve even in the midst of war. In these letters are many of the seminal ideas that Teilhard would develop in his later years.

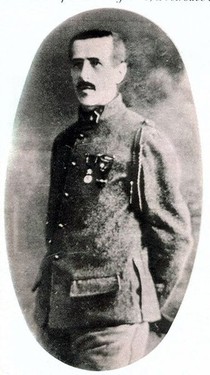

Through these nearly four years of bloody trench fighting Teilhard’s regiment fought in some of the most brutal battles at the Marne and Epres in 1915, Nieuport in 1916, Verdun in 1917 and Chateau Thierry in 1918. For his bravery Teilhard was awarded the Medaille Militaire and the Croix de Guerre. Teilhard was much admired by the men of his unit for his friendship, courage, and gallantry. He soon became known as a man who could be relied on in a difficult or dangerous situation. He would go out under a hail of bullets and calmly bring back the dead and wounded. When asked about his exemplary bravery, Teilhard replied: “If I’m killed, I shall just change my state, that’s all”. Teilhard was active in every engagement of the regiment for which he was awarded the Chevalier de la Legion d’Honneur in 1921.

Throughout his correspondence he wrote that despite this turmoil he felt there was a purpose and a direction to life more hidden and mysterious than history generally reveals to us. This larger meaning, Teilhard discovered, was often revealed in the heat of battle. In one of several articles written during the war, Pierre expressed the paradoxical wish experienced by soldiers-on-leave for the tension of the front lines. He indicated this article in one of his letters saying:

“I’m still in the same quiet billets. Our future continues to be pretty vague, both as to when and what it will be. What the future imposes on our present existence is not exactly a feeling of depression; it’s rather a sort of seriousness, of detachment, of a broadening, too, of outlook.”

Teilhard’s powers of articulation are evident in these lines. Moreover, his efforts to express his growing vision of life during the occasional furloughs also brought him a foretaste of the later ecclesiastical reception of his work. For although Teilhard was given permission to take final vows in the Society of Jesus in May 1918, his writings from the battlefield puzzled his Jesuit Superiors especially his rethinking of such topics as evolution and original sin.

He was convinced that if he had indeed seen something, as he felt he had, then that seeing would shine forth despite obstacles. As he says in a letter of 1919, “What makes me easier in my mind at this juncture, is that the rather hazardous schematic points in my teaching are in fact of only secondary importance to me. It’s not nearly so much ideas that I want to propagate as a spirit: and a spirit can animate all external presentations” (The Making of a Mind, p. 281).

After his demobilization on March 10, 1919, Teilhard returned to Jersey for a recuperative period and preparatory studies for concluding his doctoral degree in geology at the Sorbonne, for the Jesuit provincial of Lyon had given his permission for Teilhard to continue his studies in natural science. During this period at Jersey Teilhard wrote his profoundly prayerful piece on “The Spiritual Power of Matter.”

I was hoping you could clarify what TdC is saying in the first text block of quotes. To me it seems like he’s saying that pain should be a force for the realization of the Kingdom of God on Earth but that for some reason, perhaps lack of focus or unity, that this force is wasted. The problem of Evil is one of the most persistent ones for Christian apologists and it seems like the implication of what TdC is saying is that Evil exists to cause suffering which hastens the arrival of the Kingdom of God on Earth. It seems like something, however, has gone awry since people have been suffering for approximately 2000 years now and we are debatably no closer to the arrival of the Kingdom of God on Earth.

Furthermore, I’m confused about how suffering can lead to the Kingdom of God. If one is already Christian and suffers hardship it will either cause them to lose faith or they will maintain their faith. If one is a religion other than Christian the same could be said. Those without faith may acquire it in situations of hardship, but the faith they acquire will be largely determined by their peers and relatives. So it seems it couldn’t be a simple matter of suffering leading to Christian conversion because if hardship lead to net Christian conversion the world would be 100% Christian at this point.

There is a phenomenon known as post-traumatic growth, in which people who have survived hardship can grow into happier people as a result, and this could easily be attached to a Christian identity such that surviving trauma could lead to a deeper faith. But this would only apply to the survivors of tragedy. Buddhists or Muslims could easily experience the same effect.

I suppose my thoughts on this matter are shaped strongly by Evolution. To me it seems logical that, if one religion is true and others are false, then the One True Religion, in this example, Christianity, should have some sort of competitive advantage, however small, that over time would eventually result in the conversion of the entire world. Also, being the true religion it would provide strong moral guidance that would appeal to us on a deep level such that those who followed its teachings would become better people. When I think of the Kingdom of God, it looks to me like the entire world as Christian, and the people living a moral life as a result.

Hi Patrick:

Great question. The problem of evil and suffering is a tough question, especially for theists. The bottom line is that there is no fully satisfactory answer in reconciling a loving, benevolent, all-powerful Creator with the existence of evil. In my opinion, the existence of evil is the single most compelling argument for atheism.

Teilhard de Chardin addressed the question of suffering in the context of evolution. For Teilhard, God’s creation is a continuing process that started with the Big Bang, has been on-going for the last ~14 billion years and will continue for the forseeable future until the end times in the Omega Point. Suffering is an inherent part of the universe and it has positive benefits as and helps bring all of creation closer to the Omega Point, or Cosmic Christ. The death of a star begets a future star which may result in the creation of future life. The suffering of a human being can help that person both surrender his own ego and selfish desires and become more emphatic to others. The birth of a baby is a traumatic event for the baby (so much so that it is blocked out of our memories) but results in a more fulfilling life outside the womb. As the Jesuit authors of the fantastic blog “Whoever Desires” say:

“when God, who is existence itself, decides to create finite being, being that can only become perfect by means of change and growth, there will necessarily be statistical evil. All finite being necessarily involves suffering, insofar as it involves change and movement toward perfection. Teilhard sees the movement of Creation as one from the multiple to the unitary. This process requires suffering and death. Of course, these words must be used analagously, since suffering for a proton is not the same as for a dog, or for a human. But nevertheless, they all share the same genus of metaphysical evil. They all represent some kind of lack, privation, that is the result of all finite creation as opposed to infinite being. A perfect world could not actually involve true change in the realm of creatures and freedom in the realm of humans. An already perfect world would simply be an extension of God, and not truly different from God, as Catholic theology maintains.”

Very interesting quote there. Makes sense on a couple levels. But the thing I find puzzling is why should God care about finite beings becoming perfect? Why does God value “becoming” when in Christian theology God has always been? If God does not value “becoming” why create finite beings enmeshed in an evolutionary process of the kind you describe instead of creating perfect beings?

If God does value ‘becoming’ then it would seem that he prized a quality that He does not possess, making him imperfect in his own estimation. This seems to be at odds with the assumed perfection of God.

Patrick, you are asking some insightful theological questions that are beyond my ability to answer authoritatively. However, I will give it my best attempt and I encourage others who have more education than I to weigh in:

In Christian theology, God is triune (three “persons”, Father, Son and Spirit) in nature and these three persons are inherently in relationship with each other. Love is the result of this relationship and out of love God wanted to have other beings and creation to share his love with; hence the Big Bang ~14 billion years ago (of course, “time” is an artifact of the current universe and Christians believe that God transcends the universe, as well as being active within it). According to Teilhard de Chardin (and others), since that time, creation has gradually been evolving into a deeper relationship with God, from the first energy of the Big Bang, to the creation of space-time and matter, to the initial forms of unitive energy or awareness formed in simple living things to the self-conscious energy of humans (and potentially other beings in the universe) that are self-aware and have a thirst for knowledge and understanding. Humanity, and all of creation, is continuing to evolve towards a deeper understanding and relationship with God.

God wants to have a relationship with his creation, especially humans. Any meaningful relationship between conscious beings requires mutual consent. If I could unilaterally force my wife to be friends with me, the relationship would be lacking because there would be no mutual giving or surrendering to the other. Likewise, for God to have a fulfilling relationship with a human being, that person must voluntarily ascent to the relationship.

I believe humanity is at the very early stages of our evolution and that our understanding a billion years from now will make our present understanding and existence seem as primitive to our distant ancestors as the initial one-celled organisms seem to us today.

I think that the problem of evil exists, whether you posit a benevolent creator or not. Christianity has boldly taken on this problem, trying to resolve it through the relationship between the apparant separation of the Creator and the Creatures. Whether or not this dynamic is literally true is not the point, but rather that mythologically it is true when considering our human history and our relationship with the nature of the world we live in. We live in between the material world and the world of the invisibles which we sense, whether it be through dreams, or contemplating, where the heck are we in this vast cosmos we find ourselves in.

As for the existence of evil, one need only ask: How can we ever reconcile the everyday fact that life feeds on life? That contained within the nature of life itself, evil is a necessary, primary dynamic that each of us lives with or else we cease to live. Removing the idea of a creator to remove the idea of evil doesn,’t change our situation, does it?

When we look at the problem of evil in terms of the nature of relationship, between ourselves, nature and the transcendence that we all sense, and see how historically the relationship has changed, something else begins to emerge. We see that change is possible and how much humans have always strived for some sort of change – because we can’t reconcile good and evil. All cultures, Christian or otherwise, have always had a means to seek and understand who we are and where we are, in terms of transcendent powers and their relationship with us. That relationship entices us to come to know who we are and why in the world we are here (or anywhere).

Aquinas (and others) had a brilliant way of understanding the nature of evil by seeing it as a lack of the good, and not something that God created as a play thing. Evil must exist in a world where love is an act of the will, a choice. In order to truly love, we must be permitted the choice of not loving. The possibility of choosing evil by neglecting to choose love is what brings humans to search for God, or as Erik says, know themselves as God, or what I would say is participating in the Godhead, or what James Hillman would call the Anima Mundi, or world soul.

We are manifestations of God in the sense that in our seemingly finite lives, we participate in moving the story forward, in which the accumulated knowledge of all that is possible – good and evil, is passed down, shared and transformed.

Will there ever be a perfected Earth as it is in Heaven? Maybe, and perhaps in spite of ourselves, and no matter how much we always screw things up in our narrow and small piece of the whole that we participate in, the answer is still Yes.

Sorry, long reply, but I love this discussion.

Debra

Debra:

Thank you for your detailed and thoughtful reply! I too am fascinated by the question of existence, evil and free-will. I do not know if you are a science fiction fan but one of my favorite authors is Julian May who has written a fantastic series called The Galactic Milieu which draws deeply on the thoughts of Teilhard de Chardin and Carl Jung in addressing the questions of evil, purpose and humanity’s connectedness with the greater Cosmos and beyond. On my list of future blogposts is an exploration of Julian May’s books and philosophy.

I have heard of the author, but have not read his books. I used to read a lot of Sci-Fi, but recently I’ve been reading mostly non-fiction. I have a kindle though and if I can find the series for Kindle I can download samples and check it out. Thanks!

Debra

Hi Debra:

Attached is a link to Intervention, the bridge book that leads to The Galactic Milieu. Unfortunately, the Kindle version is not proofed very well.

Peace,

W. Ockahm

Thank you William. I’ll check it out.

Theologically the idea that Evil is simply the absence of Good is very attractive in that we can define Evil out of existence, exculpating God. However, this approach does not change the fact that what we call evil still exists in the world, but now we term it absence of Good.

Intuitively, we can appreciate the the absence of Good could be something different from what we call Evil if the world had been created differently. It could be boring, a neutral state. If God is creator of the universe and not just the world he also created the spectrum of possible values – a spectrum from Evil to Good are all possibilities that must have been created by God, just as he created the opportunity for Adam and Eve to disappoint him by eating from the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge. God could have removed the Tree of Knowledge and disallowed the possibility of Evil (or absence of Good in the extreme, harmful sense) but he didn’t.

The original formulation of the problem of Evil by Epicurus is:

“Is God willing to prevent evil, but not able? Then he is not omnipotent. Is he able, but not willing? Then he is malevolent. Is he both able and willing? Then whence cometh evil? Is he neither able nor willing? Then why call him God?”

If we substitute in “Harmful lack of Good” for “Evil” the question still needs to be answered.

I would respectfully disagree that defining evil as an absence of good is “defining evil out of existence.” The existence of evil creates the possibility for love, for choosing the good in a world that always includes the possibility of evil – just as the existence of non-existence, or death, creates the possibility of existence. Foreground requires background, at least in the world as we know it, the world as we experience it.

“God could have removed the Tree of Knowledge and disallowed the possibility of Evil (or absence of Good in the extreme, harmful sense) but he didn’t.” Catholics, when reading the Easter Vigil liturgy, read excerpts of the entire Old and New Testament depicting the human dilemma. They begin with this stark reminder:” O felix culpa – O happy fault, O truly necessary sin of Adam.” I have always taken this to mean that to have the physical created world, it requires these opposites. Infinity cannot be created.

But, I think our understanding of the nature of life is grossly incomplete, and especially the nature of God – even codified religion demonstrates this through its own phenomena or revelation seen in the movement from Old Testament to New Testament.

Not liking evil, or God as he is depicted by any religion, will not change our dilemma, or move the story along to a deeper way to understand and reconcile our experience of living.

Respectfully,

Debra

I understand your argument but the Contrast argument – that Evil is necessary for the existence of Good – is different than the Evil-is-the-absence-of-Good argument. The problem with the Contrast argument is that it assumes that God was constrained in certain ways when he created the Universe. That is God was required to allow for Evil such that Good could exist. This argument makes intuitive sense to us because we are use thinking about binary opposites. Light/Dark, Good/Evil, Love/Hate, etc. and even when there exists a spectrum between those two opposites their existence in some idealized (abstracted) manner is assumed. That is, I may never experience “True Evil” but I tend to assume it exists in some way, likewise for “True Good.”

In physics, a analogy for this could be a magnet – with both a positive and a negative pole. Because of the way magnets work (I won’t get into the physics) you will always have both a positive and negative pole on a magnet. Physicists have theorized the possibility of a magnetic monopole (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Magnetic_monopole) which would have only one pole of the magnet.

If we assume that God created the Universe, not merely the matter that makes it up but the laws of physics that govern it as well, then he could have created a Magnetic monopole just as he could have mandated a different universal gravitational constant. Or dispensed with gravitation entirely, or change the way in which matter interacts. Not only this but God could have created a system in which things didn’t exist in binary opposites. That is you could have Light and less light, without true Darkness; Love and less love, but no Hate; Good and less-good, but no Evil. If this was not within God’s power then he is not omnipotent and therefore not God.

So in the end, the Contrast argument suffers the same problem as the Evil-is-the-absence-of-Good argument in that it merely forces us to re-phrase the Question of Evil. Our new formulation of the Problem of Evil, given that Good currently requires Evil for contrast, is:

“Why did an Omnipotent, Benevolent God create a world in which Evil was necessary for Good to exist, when he was capable of doing otherwise.”

Disclaimer – I’m not trying to tell you what to believe, or how, but merely engaging with an interesting theological problem. For me the problem of Evil is a terribly interesting one and I really enjoy learning more about it through argumentation. This post is made respectfully in appreciation of this blog’s tradition of reasonable, rational discourse.

Hi Patrick,

I am happy to engage with you these very important and compelling questions. By nature, even if I may sound like I have a firm view, I hope it will help to admit that I don’t, because as my life goes on, my understanding and emphasis moves, not in any particular direction, although I like to think I moving closer to the truth, I assume we are aiming in that direction. But the goal is more about what is learned and grasped along the way, yes? Okay, that shall be my disclaimer for all that I have to offer here.

Ultimately, even if we don’t like it, the nature of God is not in our hands. If God did choose to create the world and allow evil to exist, neither our lack of understanding why that is so or our need for moral approval of the reasons would stand as proof that God does not exist.

I guess I am puzzled by your premise here:

“Why did an Omnipotent, Benevolent God create a world in which Evil was necessary for Good to exist, when he was capable of doing otherwise.”

Omnipotent makes a certain amount of sense, but benevolent is kind of slippery for me. I’m not sure I would use the word benevolent as an all-encompassing way to describe God, so I can’t prove your definition of God for you. Does that make sense?

But, I will say that the contrast argument to my mind more closely resembles the world as we primarily experience it even if only because the premise of our life is that we live and we die. Now that is some contrast, yes?

I think our createdness, creaturelyness, would be the only way to know in the sense that we experience it and I think God knows that. When that is the premise, what follows may be a slow uphill climb from the absence of life to the fullness of life. The gradations in between will by necessity include all the shades of dark and light, evil and good, being and non-being.

Thank you for this engagement, it is something I enjoy very much!

Debra

Thanks for that contribution, I think I understand your point of view better. Usually in my theological musings, I tend to argue from the common assumptions made in the Catholic theological tradition, because to my mind that is the most rigorous of Christian theological traditions. In that tradition God is, as a matter of faith, defined as Omnipotent and Omni-Benevolent (is that a word?). It seems like your God is different in important ways from the traditional Catholic God which is usually my point of reference in these discussions.

Also, as to your point:

“Ultimately, even if we don’t like it, the nature of God is not in our hands. If God did choose to create the world and allow evil to exist, neither our lack of understanding why that is so or our need for moral approval of the reasons would stand as proof that God does not exist.”

I’m afraid you’ve rather missed the mark here while being entirely correct. You are absolutely correct in that God making no sense is not evidence of God not existing. Where you’ve missed the mark is A) The burden of proof and B) The point of the Problem of Evil.

A) The burden of proof in discussions of the existence of God rests on those asserting a positive claim. That is, like any other positive assertion of the form “There exists a 1935 Volkswagon Beetle” would require evidence to support this claim. In the absence of evidence we exist in a state of ignorance, but by gathering further information we can make an estimation of how true this statement could be. For example, research will show that the first Volkswagen factory was constructing starting in 1938 and that only a few cars were produced prior to WWII. This would lead us to think that it would be very unlikely for it to be the case that there was a Volkswagen Beetle made in 1935 unless it was some sort of advanced prototype. In the absence of specific evidence for that we would think that the existence of a 1935 Beetle would be very unlikely and we would operate under the assumption that it probably doesn’t exist.

B) The Problem of Evil is a lot like knowing that the first Volkswagon Factory was built in 1938. What the Problem of Evil is NOT is proof that God doesn’t exist. What the Problem of Evil IS is a demonstration of the logical inconsistency of the traditional definition of God with observed and universally agreed facts about the world we inhabit. That is the definition of God as Omnipotent and totally benevolent is logically inconsistent with the existence of suffering in the world. So the function of the Problem of Evil is not to disprove the existence of God, but to help us, in our state of ignorance about the existence of God, to form an opinion about how probably his existence is, given the facts at hand. Like the 1935 Beetle, God could exist, but the Problem of Evil influences our estimation of how probably that is to be True towards less likely, rather than more likely.

Oh, I screwed up, there is a 1935 Volkswagen Beetle prototype on record! Right, let’s say 1930 for the example then!

Patrick and Debra:

Thank you so much for your insightful contributions! Pardon me for weighing in on this fascinating discussion but I wanted to make a couple of points:

To Patrick: You state that “The burden of proof in discussions of the existence of God rests on those asserting a positive claim.”

I strongly disagree on this statement. This is a false argument put forward by atheists to put theists on the defensive. The “burden of proof” on whether there is a Creator that exists outside of the material world is a question that should be examined de novo, that is there should be no presumption as to whether there is or is not a Creator. All of the evidence, both in favor of and against a Creator, should be examined, discussed and debated to arrive a conclusion. This conclusion is inherently probabilistic in that it is not capable of proving its truth or falsity using the scientific method. I posit that looking at all of the evidence in favor of a Creator (the mathematical beautify embedded in the fabric of the cosmos, the historical fact that different cultures can arrive at similar moral codes, the subjective feelings of love and connection associated with holding a child, the common human longing for ultimate Truth and meaning in life) outweighs the evidence against a Creator (the existence of evil). From a pure logical standpoint, I can get to a 75% probability of a Creator. Beyond logic, with unique personal experiences not capable of scientific explanation and revelation of others, I can get to a 95% probability. I will never get to 100% (I will never get to 100% certainty on anything, including this statement :-)) but that remaining 5% is where the common experience with non-believers is meaningful.

To Debra: I absolutely agree with you the a human’s understanding of God (both the individual monad and the collectively humanity) evolves over time. Like all other knowledge, there has been a slow but gradual evolution of our understanding of God. This will continue to be so. I do want to try to bridge the difference between a statement you made “benevolent is kind of slippery for me” and Patrick’s argument for the existence of evil as evidence of a non-benevolent God (and hence no God per the Christian tradition).

I acknowledge that the existence of evil is problematic for the Christian notion of a benevolent God. However, I do believe in a benevolent God that consists of conscious love energy (to the extent that a limited human mind can comprehend God). The issue is the definition of “benevolent”. God’s all-knowing benevolent is different than a limited human understand of benevolent. There is pain and suffering in this world, but it can be used as an opportunity to grow, both individually and collectively, and connect with a wider purpose. Every death of a star or living organism gives life to another. The struggle in the journey makes us stronger. As a rough analogy, if I have olympic athletic talent, I have may a desire to watch TV and eat Doritos. However, a “benevolent” coach may exhibit tough love and force me to train hard with lots of pain, effort and sore muscles. The process of training through a coach with “tough love” makes me a better athlete. Similarly, in my own life, the periods of pain and suffering have forced me to step outside my interior ego and see the broader perspective.

I want to thank both of you for stopping by and for your great insights on this issue.

Peace,

W. Ockham

Hi Sir William,

I hope we are not overstaying our welcome here on your blog! Please feel free to say so if the dinner bell has rung (or the call to vespers) and we should all be moving on.

I like and agree with your definition of benevolent and it refreshing to hear it articulated as well as you do.

Having been a hard-core atheist myself at one time, I know and respect that the premise, “there is no God,” becomes just as much a lens used to build every brick of cosmology upon which all other future ideas and arguments will then nest.

But, I know that it’s the premise, God, or no God, that determines how all ideas are heard. And, that, for me is why I am not a materialist, or an atheist anymore. The premise of materialism itself is just as much a mental construct as is a supernatural contemplation of the nature of God. We are all at the mercy of our ability to receive the world through our senses, and then imagine that sensed world into meaning, even if we choose a science of materialism for an explanation of experience because of the measurability and predictability of so-called material things.

I agree Sir William, that God is benevolent even though there is evil because the only way to experience anything is to be, rather than to not be, because not being means we are not infinite and being born means we die. Death is the ultimate evil, yes? The very threat of it taints our existence, although I agree that the possiblity of being God, over and over in every form of life, solves this problem, even if it doesn’t seem to remove all suffering.

Peace to all here!

Debra

Debra:

Thank you very much for your outstanding response! And no, the dinner bell certainly has not wrung and I enjoy the discussion as these are meaningful (and fun!) topics. The only thing I will add is that while death can be (but does not have to be) an evil I do not believe it is the ultimate evil. I believe death is a transition to the next phase of existence, of which we are hardly able to comprehend.

The analogy I use is to a baby’s existence in the womb. It is a warm and safe existence that allows the baby to grow and develop. Suddenly, a violent event occurs and a baby is thrust into a seemingly hostile environment and overwhelmed with physical sensations. The experience is so traumatic that it is not part of our memories. However, as we grow, the wonders of this phase of existence become manifest to us and we would never want to go back to the womb. Similarly, I believe death is a transition phase that leads us to a beautiful existence.

Peace,

W. Ockham

Hi William,

Yes, absolutely, death is a transition as is birth.

Perhaps for those who struggle to find sense and meaning in our existence, and therefore not comfortable with the idea that we are anything more than physical blobs of stuff, temporarily here, our consciousness a by-product of the material nature of our bodies and nothing more, that death, non-being would be the ultimate evil.

Peace to you!

Debra

“I strongly disagree on this statement. This is a false argument put forward by atheists to put theists on the defensive. The “burden of proof” on whether there is a Creator that exists outside of the material world is a question that should be examined de novo, that is there should be no presumption as to whether there is or is not a Creator.”

William, my intent is not to put anyone on the defensive by merely to apply equal standards of evidence to all propositions, whether they be about the existence of God, the orbit of the planets, or the price of bread in Chicago. I feel that to ask for a different set of standards for any one proposition is to commit the logical fallacy of Special Pleading (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Special_pleading). I’m rather confused by your statement as well because I feel that you go on to echo my position – namely that in the absence of evidence for a positive claim (the existence of God) we are left in an undecided position. When atheists assert that positive claims require evidence they are not saying (or should not be saying!) that the Non-existence of God is some sort of default position that we assume. What we actually are left in is a position of ignorance coupled with a probabilistic estimate of how likely the proposition is to be true. Because many people assign a low probabilistic value to the existence of God their position is functionally very similar to the position that God does not exist, but it is an important difference (a lot of atheists screw this up in my opinion).

We obviously disagree on how the Problem of Evil influences that probabilistic value. Furthermore, I confine myself to logic and objective evidence on this topic whereas most, if not all, theists necessarily rely on Faith rooted in subjective experience. Without Faith, I’m sure you’d agree, belief in God is empty. If God could be proven through logic and evidence then believing in him would be no great matter and probably would not merit the rewards God reserves for believers such as remission of sins, a positive afterlife experience, etc.

It is interesting that you quantify your belief in God as a percentage – it raises the interesting question of what is the threshold of probabilistic belief required by God? If you are only 25%/50%/75% certain of His existence do you go to hell when you die? (I’m not trying to be provocative here, I’m genuinely curious what you think).

“Patrick’s argument for the existence of evil as evidence of a non-benevolent God (and hence no God per the Christian tradition).”

I was not attempting to argue for the existence of a Malevolent or indifferent God, but merely to point out that in our human understanding the existence of evil is not primae facie compatible with the idea of a completely benevolent and omnipotent God. This means, as we have discussed, that some element of the proposition is incorrect as stated. Possible solutions include A) No God B) Malevolent God C) Human Inability to Comprehend the Nature of God, etc.

While I respect the common answer that suffering is required for spiritual development, there are numerous logical problems with this solution (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Problem_of_evil#Soul-making_or_Irenaean_theodicy) and it seems that the solution best compatible with a theistic viewpoint is that the nature of God is intrinsically unknowable to our human reason.

Debra, I’d like to point out that my worldview as an Atheist is not built on a foundation of assuming God’s non-existence. It is based on certain standards of observable evidence and logical coherence. That is the lens through which I view the question of the existence of God.

“the premise, “there is no God,” becomes just as much a lens used to build every brick of cosmology upon which all other future ideas and arguments will then nest.

But, I know that it’s the premise, God, or no God, that determines how all ideas are heard. And, that, for me is why I am not a materialist, or an atheist anymore. The premise of materialism itself is just as much a mental construct as is a supernatural contemplation of the nature of God. We are all at the mercy of our ability to receive the world through our senses, and then imagine that sensed world into meaning, even if we choose a science of materialism for an explanation of experience because of the measurability and predictability of so-called material things.”

It seems from the above quote that you regard the theistic and atheistic mental constructs as intrinsically equal – or rather that you don’t view any mental construct as superior to any other. I’d be very interested in your additional reasons for choosing the theistic viewpoint.

“When atheists assert that positive claims require evidence they are not saying (or should not be saying!) that the Non-existence of God is some sort of default position that we assume. What we actually are left in is a position of ignorance coupled with a probabilistic estimate of how likely the proposition is to be true.”

I agree and apologize if I misinterpreted your original statement. Unfortunately, too many atheists I have encountered presuppose an atheistic position as the default and place the burden of proof on believers. It sounds like we both agree the issue should be examined de novo.

“It is interesting that you quantify your belief in God as a percentage – it raises the interesting question of what is the threshold of probabilistic belief required by God? If you are only 25%/50%/75% certain of His existence do you go to hell when you die? (I’m not trying to be provocative here, I’m genuinely curious what you think).”

The quantification stems from my training and profession. I have a finance background and am a corporate attorney so I analyze risk and alternative scenarios for a living, which is part of the reason I find philosophy and theology fascinating. I would approach your question on “probabilistic belief required by God” differently. My faith tradition says that heaven is an eternal union with God and hell is an eternal separation from God. Heaven can be obtained, through the grace of God, by conforming our will and actions to the purposes that God designed for us; specifically, loving God and neighbor with our whole heart, soul and mind. Humans in general (and certainly me specifically) fall short of that high standard but the virtue is in trying. It is not unlike being in a relationship with a spouse, child or friend. We can believe in the relational concept and understand what the ideal is even if we fall short. I also do not believe that heaven/hell is a binary concept, which is why the Catholic idea of purgatory is intellectually appealing. For non-believers who do not believe in a Creator, almost by definition it will be a challenge for them to be united with the Creator. However, even that position in Catholic teaching is highly nuanced, which is completely missed by the mainstream press reporting on some statements by Pope Benedict and Pope Francis on this issue.

Peace,

W. Ockham

God has limitations , “Christianity and Evolution, ” see page 82. , “we used to accept, at least implicitly, that God was free and had the power to raise up participated being in any state of perfection and association he chose. He could position it, as he pleased, at the level of any point whatsoever between zero and infinity. It seems to me impossible to reconcile these imaginary views with the most fundamental conditions of being, as manifest in our experience. ” See also FN #3, page 82 “… Yet there are many things which it is physically impossible for God to do: He cannot for start, make something past never to have existed” (Note by Pete Teilhard)

Personally I have no problem accepting the proposition that the only way human life could be created is precisely in the world that exists. I also can accept the proposition that God cannot physically intervene and alter the natural workings of the physical laws He created without changing the natural unfolding And progression of evolution. BUT what I find most difficult to accept is why He chose to go ahead with creation knowing the unbelievable extent of collateral damage. My first question if I ever get to meet Him – will be “What were you thinking when you undertook creation?”