- About

- Staff

- Issue 1 (Deaths)

- Issue 2 (Bodies)

- Issue 3 (Quests)

- Issue 4 (Institutions)

- Issue 5 (Beldams)

- Issue 6 (Seas)

- Issue 7 (Skins)

- Issue 8 (Dreamings)

- Issue 9 (Architectures)

- Issue 10 (Governments)

- Issue 11 (Possessions)

- Issue 12 (Animals)

- Issue 13 (Births)

- Issue 14 (Musics)

- Issue 15 (Diseases)

- Issue 16 (Trades)

- Issue 17 (Gothics)

- Issue 18 (Magics)

- Issue 19 (Voyages)

- Issue 20 (Birds)

- Issue 21 (Cocktails)

- Issue 22 (Archives)

- Issue 23 (Battles)

- Issue 24 (Botanicals)

- Issue 25 (Prehistories)

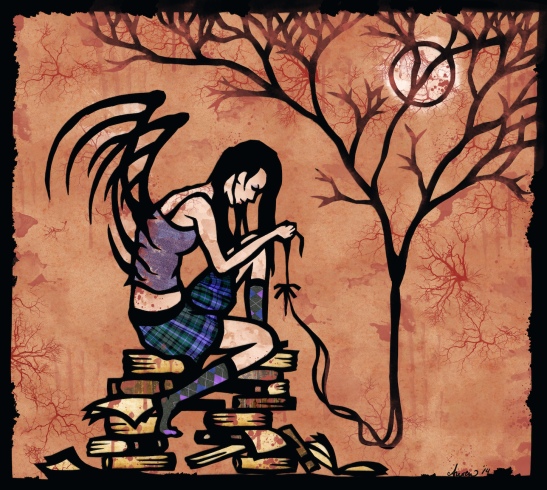

Unravelling, by Julia August

I.

The witch’s nails were long and white.

“Follow your dreams,” she said and flicked her spindle so that the crosspieces blurred. It was a Turkish spindle of the sort that comes apart into wooden fragments. I couldn’t see her eyes, which troubled me. “Yes. That sounds good.”

“Why?” I said. “My dreams are boring and ordinary. I know where they go.”

“Dream more exciting dreams, then,” said the witch.

She set the spindle spinning again. I thought she was probably more interested in her spinning than in my problems. It didn’t help. When I ask a witch for advice, I’d like her to pretend to be interested in what I’m asking her about, at the very least. Maybe I should be reasonable and admit I wasn’t bringing her any particularly interesting problems. But there’s nothing particularly reasonable about resorting to witchcraft and I didn’t feel like being reasonable then.

“Alpaca is such soft wool,” said the witch. “And chocolate brown is a nice colour. Almost as dark as your hair. I have a hundred grams of angora top dyed with cochineal, though. Now there’s a good colour.”

“Dead beetles,” I said. “Why are you telling me about wool and dyes? I didn’t ask you about that.”

“No,” said the witch. “So what do you want me to tell you? ‘Be yourself’? I wouldn’t. It never helps.”

“But it’s easy. I’m too lazy to be someone else.”

“Then why are you complaining? Look, I have silk to spin. I dyed it with madder. Never let me dye silk with madder again. The root never comes out. And I dyed it in a bath that I’d already used for wool with a copper mordant, so it’s brown rather than red. But a good colour for all that. And silk. Lovely stuff, silk.”

“I’m not interested,” I said crossly. “I don’t want to know this.”

“Then why are you here? Because I can read your mind and tell you to do what you want to do anyway? Honestly, did you really think I would?”

“Next time, I’ll ask my mirror,” I snapped. “Honestly!”

I heard her humming as I stamped out. She’d probably forgotten me already.

II.

I met the witch again in Celephaïs, where I had gone to dream exciting dreams. Or maybe it was Larkar or Aráthrion or Argun Zeerith or even the snow-capped mountains above shining Gondolin. She wound her thread around the spindle shaft and told me that privatum consilium was looking very promising. Diogenes had kindly provided her with a hundred passages, she said, many of them relevant. She might get a chapter out of it. That would make up for reading Silver Latin where apud becomes aput and all the old familiar words change shape and vanish from her dictionary.

“Do I look interested?” I asked. “I wasn’t looking for you. I came here to dream.”

“I’m not stopping you,” said the witch. “Dream on.”

I rolled my eyes. The air was cold and crisp and clear, a mile and more above the nameless city’s gleaming domes and pillars and its chalcedony and onyx steps. The valley plunged too far below to see whether weeds grew in the city’s streets.

The witch’s thread snapped. “Drat,” she said. “Would you get that for me?”

She was perched high on a slab of rock, her heels tucked up and her knees jutting out under the folds of her skirt. I retrieved the spindle from under a nearby bush.

“Thanks,” said the witch. “I do that embarrassingly often. Alpaca. Lovely stuff.”

“I’m still not interested. Really.”

The spindle blurred between her fingers. “Your loss. I don’t know why you’re dreaming other people’s dreams anyway. Trying to distract yourself? You won’t get anywhere by it. Look, is that a god coming over the hill?”

An impossible shadow fell over the shining city. The god leaned on a flat-topped mountain and peered down into the valley, smiling. Far in the blue-tinged distance, other figures were wading through the mists.

The witch had begun to wind up her thread again. Across the valley, the god pointed at the city and spoke a word. Out of the distant mists leapt a scrawny creature that howled down the mountainside towards the shining domes. A trail of damp paw-prints lingered in its wake.

“They’re destroying the city?” I said. “What’s it done?”

“Who knows? The gods round here are capricious and inclement and liable to set a pet on you if you pray to Them on a slow day and They want a laugh. You’d better get used to it if you want to stay here.”

The gods were gathering around the rim of the valley, laughing and pointing down at the city. “Thanks,” I said sourly. “It can’t be Gondolin, anyway. Where are you going?”

“Away,” said the witch, slipping down from her seat. She had a bag slung over her shoulder in which she stowed away her spindle and the rest of her unspun wool. “Nice place to visit. I wouldn’t want to stay.”

III.

She came back into my dreams with a collection of anti-Antonian polemics in her hand and glanced around with interest. I thought it must be interest, anyway. She struck me as being inappropriately real. “What’s going on here?” she said. “I don’t remember this.”

“It isn’t written yet,” I said. “You wouldn’t.”

“Oh,” she said and watched for a moment or two. “That woman doesn’t look very happy.”

“Her mother’s dying,” I said. “She isn’t.”

“Sad,” said the witch. “But everybody dies. Is that her child? Is it fair or dark, I can’t quite tell?”

“I haven’t decided yet.”

“Which side of the family do you want it to take after? I suppose you haven’t decided that yet either. You really are dreadful sometimes. Have you written that email yet?”

“No,” I said. “Shut up. I didn’t invite you here. I don’t know why you’re here at all.”

“You asked for my advice,” she said. “Is it my fault if you don’t really want to hear it? He won’t just disappear, you know.”

“I know that,” I said. “And those speeches won’t make their own notes, will they?”

“Very true,” said the witch, and went.

IV.

“So,” said the witch. “You’re ill and you didn’t write that email and now you have to do it when your head’s hardly working and you don’t know what to say? I’m not sure why you’re here. Am I meant to be sympathetic? I told you it wouldn’t go away if you ignored it.”

“Sometimes things do,” I said. “It might.”

“No,” she said. “You need some moral fibre. Swearing at me won’t help anything.”

I didn’t say anything for quite a while. Eventually she tracked me down in a cozy internet den full of people being entertainingly acidic. “For goodness sake!” she said. The spindle in her hand was beginning to look like a spiky little mace. “This is ridiculous. Write that damn email and write it now. I don’t care if you do feel ill, that’s no excuse. Do it now and get it out of the way.”

V.

“Now really,” said the witch. “‘Sometimes I think you underestimate how uninteresting I am’? Do you really think that’s going to work?”

“No,” I said. “It never has before.”

“Then why bother?”

“I had to say something,” I said. “Oh god. This isn’t going to be fun.”

VI.

“I didn’t want to be responsible,” I said. I think I told the truth. It’s so hard to know sometimes. It’s not as if my head was clear enough to tell. I pushed my hand distractedly through my hair. “Oh god. Am I going to regret this?”

“Maybe,” said the witch, who has no heart. She was spinning again, the blurring crosspieces of her mace-like spindle poking out of a gathering ball of brown wool. “It had to be done.”

“I could have—”

“No!” she said. “You took long enough to do it.”

“But what if—”

“Be honest. It’s a virtue. Or maybe a grace. It’s a good thing, either way. So what if you’re responsible? Someone had to be. It wasn’t going anywhere. You know that. So sometimes people’s feelings get hurt. It happens. You need to grow up and be honest with yourself and everyone else and damn well learn to handle it. All right?”

“Not really,” I said unhappily. “Though I know you’re right.”

“Of course I’m right,” said the witch. “Now stop whining. You’re ill. Get some sleep.”

VII.

I met the witch by moonlight on Kingsgate Bridge. She was leaning on the concrete balustrade and watching the water down below ripple like black plastic. I could see only the wildness of her wind-whipped hair. Behind her in the river lay the dull gold of street-lights from the brutal sixties architecture and the old bridge further downstream. Ghostly, the cathedral arose above a tracery of tangled skeletal trees.

“I forgot my spindle,” she said. “Such a pain. I had half an hour to kill before the evening seminar. What did you want?”

“I’m not sure,” I said. “I’m not sure at all.”

“In that case, I can’t help you. Come back when you have something useful to say.”

Overhead, half a white moon gleamed like a piece of communion wafer. “I don’t want to talk about it,” I said. “Can’t you read my mind?”

“Well, yes,” she said. “But other people can’t. The world doesn’t revolve around you, you know. People don’t know what’s in your head unless you tell them.”

“Fine,” I said. “I know that. Now will you read my mind?”

“No,” said the witch. I saw her fingers twitching, as if remembering the weight of that absent thread. “I have better things to think about.”

VIII.

“Why do you write romance?” said the witch. “Is it so you feel less alone?”

“Why are you asking me questions?” I said. “I thought you could read my mind.”

“I can,” she said. “I know you want to be distracted. Besides, maybe you should stop and think a little harder about what you’re doing. Where you are. Why you’re here. How you ended up here. And what you’re going to do about it.”

“I’m not sure I want to talk to you just now,” I said. “Sometimes I wish I hadn’t gone to you in the first place. Maybe I should get out of the house for a bit.”

“It’ll still be there waiting for you when you get back.”

“I know that.”

“Putting things off never solved anything,” said the witch. “Haven’t you worked that out yet?”

IX.

“If you didn’t want to be analyzed, you should never have taken up with a psychology student to begin with,” said the witch. “Now go and finish reading his email. It probably won’t be as bad as you expect. You know how much he likes to talk things through in person.”

X.

I met the witch outside the library this evening. “I’ll walk you home,” she said and matched her steps to mine so precisely that I could only hear my own feet on the ground. It was dark already and above the town the cathedral’s spires speared up into the charcoal night.

She was telling me about Cicero as we crossed Kingsgate Bridge. I didn’t listen; I’d heard it all before. And I had other things on my mind anyway. We paused at the far end where someone had torn apart a book and left the scattered pages to be trampled by students passing between Elvet Riverside and the Bailey.

“Take me apart,” I said, and saw myself suddenly dissected in metaphor and fact, split open throat to crotch with ribs cracked back like bloody wings. Skin stripped away, flesh scraped from bone, laid bare my barely beating heart. And set out in suitably sterile fashion my pride, my laziness, my lack of compassion, and affectation where affection should be. All icy absences and unpleasant facets labelled and enumerated with perfect clarity. Myself in metaphorical pieces (and literal ones) so that a different total might be reached by summing up a different collection of component parts.

The witch cleaned her white nails. “No.”

We went up the cobbled path between colleges. “Please?” I said.

“No,” she said again. “Not all at once. A bite at a time, now, I can do that.”

XI.

I dreamed the witch cut out my heart that night. She slit me open with a kitchen knife and prised my ribs back with the minimum amount of mess. It didn’t hurt. Her fingers slid between the tight-packed contents of my chest cavity like any other organic crevice, long nails snagging on the edges of organs.

With a twist of her wrist, she plucked out my heart. Blood dripped from her fingers. She gouged her thumbs into its gaping holes and tore it piecemeal apart, feeding the bloody chunks into her mouth and chewing through a bloody smile.

I woke up with the witch’s hand between my ribs. “Hold still,” she said. “This won’t hurt a bit.”

XII.

The witch set down her spindle on the middle of the bed, a wispy fluff of black puffing over the green quilt my mother made for me to take away to university. “This is ridiculous,” she said and sounded more than a little irritated. “You’re meant to be brighter than this.”

I twisted my fingers into the end of an unravelling plait. “I know,” I said. “But academic intelligence doesn’t necessarily translate into real-world sense?”

“Nice try,” she said. “Not good enough. You know that. Honestly!”

This time I didn’t say anything. She folded her arms across her chest. Her nails were as long and white and sharp as polished seashells.

“Honestly,” she said again. “This is ridiculous. You need to do something about it.”

“Like what?”

She had a drawstring tapestry bag in muted shades of damask. “This would be a start,” she said and brought out a kitchen knife.

It looked as sharp as her fingernails. “Oh,” I said. “Won’t it hurt?”

“Don’t be ridiculous,” she said and set the edge against her throat. “Only real people feel pain.”

XIII.

I watched a biology teacher skin a rabbit once. He’d had a lot of practice. He used to get them from the farmers near the school. The most we ever did ourselves was cut up kidneys and once, I think, a heart.

The witch’s skin came off more easily than I expected. Her organs glistened beneath the blood-strung bones.

Go on, she said. Do it.

I was halfway through her liver before I remembered I’d meant to stop eating. I’d had pie and cake and at least one barbequed kebab the day before, not to mention several proper meals over the weekend. I wasn’t hollow, yet.

You’re being an idiot again, said the witch, without moving her jaw. Her eyes bulged in her stained and lidless skull. Don’t even think about talking yourself into an eating disorder on top of everything else. Just get on with it.

Her heart was missing. I didn’t say anything. I probably didn’t need one anyway.

I picked up her skin. It was heavy in my hands and oddly supple, paling in places to translucency. The other side was sticky with blood and other fluids. When I inched it on, carefully to avoid further tears or stretching, it clung to me like cling film. I flexed my fingers inside her hands and ran her nails along my wrist.

I nudged her eyelids into place over my eyes. Inside, her face tasted of blood, which is to say of salt and iron.

I looked in the mirror and found her looking back at me.

There you go, said her voice in the back of my head. It’ll do. For now.

“For now,” I said. “It’ll all be fine?”

No promises, said the witch. But it should be better. And you know what to do if it isn’t.

“Yes,” I said, and said it in the witch’s voice. I had her spindle in one hand and her knife in the other, still slick with blood. “I’ll go and see a bloody doctor. What about you?”

You shouldn’t need to ask, she said. I always come back.

XIV.

I met the witch one last time on my way back from the fairy woods. Her hair curled close around her ears in loose and woolly plaits; her skirt swirled at her ankles. She looked like an Enid Blyton schoolgirl let loose for the holidays. “Do and be damned,” she mouthed at me and smiled.

We went back over the trollish bridge. “I will,” I said. “I think I will. I didn’t expect to meet you here.”

“More fool you,” she said. “Where are you going, home? In the sun?”

“I ran out of wool. I could just fetch more. But what I really want to do is to curl up under that tree in the sun and the summery woods and forget everything and sleep forever.”

“Do it,” she said with her sharp smile, the tassels of her unravelling plaits curling under her chin. “Do it and I’ll hold your hand.”

I ignored her. I was out of the woods now and back into the street.

*

Story copyright © 2015 by Julia August

Artwork copyright © 2015 by Paula Arwen Owen

Julia August wishes her inner witch would be more sympathetic sometimes, but witches don’t generally appreciate sympathy, so it seems unlikely. Her short fiction has appeared in various places, including the “Women Destroy Fantasy!” special issue of Fantasy Magazine, PodCastle, Goldfish Grimm’s Spicy Fiction Sushi, Lightning Cake, Lackington’s (Issue 2), and the anthologies Triangulation: Parch and Star Quake 2. She is @JAugust7 on Twitter and j-august on tumblr.

Paula Arwen Owen (artwork) is an illustrator and graphic designer from New York who works in hand-cut paper silhouettes and collage. Her fantasy and horror illustration work has appeared in magazines such as Mythic Delirium, SageWoman, and Goblin Fruit. She has illustrated book covers such as Immigrant by Cherie Priest and The Button Bin by Mike Allen. Paula’s artwork, prints, and greeting cards are available through her website and in retail stores.