The first fire of the hostiles was delivered at the Indian police, and by the time we had gotten to their assistance the firing had ceased and the Indians were circling around on their horses beyond rifle-fire.

As a follow up to the account by First Lieutenant John Kinzie, 2nd Infantry, of his recollection of Wounded Knee and his wounding in the battle, I will stay briefly with the 2nd Infantry Regiment. Another officer of that storied unit penned an account of the activities that occurred at the Pine Ridge Agency immediately following the outbreak of hostilities at Wounded Knee.

Thomas H. Wilson was a second lieutenant in Captain Charles A. Dempsey’s B Company, 2nd U.S. Infantry Regiment, during the Pine Ridge Campaign of November 1890 – January 1891. Wilson was an officer that had risen from the enlisted ranks. He began his military service in 1878 with the 4th Cavalry and rose to the rank of sergeant in K Troop before receiving a commission in 1882. Subsequent to the Sioux campaign, Wilson was promoted to first lieutenant of the 5th Infantry and later transferred back to the 2nd Infantry by the time he wrote his account of the 29 December 1890 attack on the Pine Ridge Agency. There are numerous newspaper reports on the activities at Pine Ridge that tragic day, as most of the reporters in the region were at the agency. However, Lieutenant Wilson provided a rare glimpse from an infantry officer’s perspective of the engagement at Pine Ridge.

THE ATTACK ON THE PINE RIDGE INDIAN AGENCY, S. D.

AN UNWRITTEN CHAPTER.

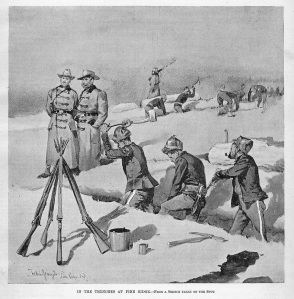

Frederic Remington’s “In the Trenches at Pine Ridge” appeared on the cover of Harper’s Weekly Magazine at the end of January 1891.

The outbreak in South Dakota in the winter of 1890-91 has been ventilated by many able and competent writers, and while they have all given a great deal of space and time to the Wounded Knee and Mission fights, the incidents of the attack on the agency, which took place the same day as the Wounded Knee fight, have not yet been fully given to the public.

In order to give a clear and graphic account of this affair it will be necessary to go back to the beginning of the movement of the troops in the early winter. On the morning of the 18th of November, 1890, the Second U.S. Infantry was suddenly placed on waiting orders, to proceed at a moment’s notice to the Sioux Indian Agency at Pine Ridge, S. D. It was thoroughly unexpected; there had been no news of any threatened outbreak or trouble on the part of the Indians, and the Department order contained no specific information. All the day the companies were busy packing rations, tents, extra ammunition, and clothing.

At noon the order was changed to four companies, A, B, C, and D, to leave, via the Elkhorn Railroad, at 7 o’clock P.M. the same day. The movement was a complete surprise to everybody. Of course, we all knew it meant a few weeks’ hard work, and possibly an all-winter’s campaign. About 6.45 P.M. the first call was sounded, and fifteen minutes later the command had formed on the parade-ground.

Adieus had already been said, and then the little command started to march to the station to the inspiring strains of “The girl I left behind me.” The kindly darkness hid the weeping women and children, and just as the train started the band changed to “Auld Lang Syne.” Even the bachelors, careless and debonair, felt a moment’s regret as the sweet strains were wafted to their ears. Faint and fainter grew the music, and then we were rushing along, with no sound but the throbbing and sobbing of the great iron monster pulling its load of “boys in blue.”

The trip on the railroad was a thoroughly uninteresting one; no information could be gathered along the road, not even any rumors of an outbreak or anticipated trouble.

The troops disembarked at Rushville at about 2.30 P.M. the following day; the wagons were immediately packed and made ready for travel; dinner was hurriedly cooked by the companies, and 5.30 o’clock P.M. found us on the road to the Pine Ridge Agency, S. D., about twenty-eight miles distant.

It was a memorable march. The night came on us at about 6.20 o’clock, and when the sun had dropped behind the western hills the air grew cold and chilly. On and on we tramped. By and by the stars came out, and by their light we could see the road leading on and on, and on both sides of us the bleak and barren hills of South Dakota. At about 10.30 o’clock that night a halt was ordered for an hour or so, and then, after a cup of hot coffee and a few hard-tack, the wearisome march was taken up. We were in an entirely new country, at least to us; the drivers knew nothing of the condition of the roads, and, in consequence, we were compelled to wait hours at a time to right capsized wagons and give the train time to close up. No smoking was allowed; the majority of the enlisted men and all the officers were without overcoats, and it was seven o’clock the next morning before we reached the agency. Our condition and peace of mind can be imagined. Our coming seemed to create very little impression on the Indians; they received us stolidly, paid scarcely any attention to our movements, and in the course of a few days we had settled down to camp-life at the agency. A few days later we were joined by the other companies of our regiment, thus constituting a force of about four hundred men. Before proceeding with my little narrative it may be well to look at the aspect of affairs at the Pine Ridge Agency about a month or so previous to the movement of the troops.

The new agent (since removed) took charge of the agency about the 1st of October, and found the ghost-dance in full swing. “There was a general discontent throughout the Sioux nation, the troubled condition added to and fomented by Red Cloud, Sitting Bull, and other agitators. But I do not hesitate to say that had a man of nerve and experience, who knew these Indians and was known by them, backed by a disciplined force of Indian police, been in charge, an abandoning of the agency and the calling of the military would no more have been necessary than were such measures at Standing Rock.” (From Herbert Welsh, in Scribner, April, 1891. Vol. VII. N. S.—No. 6. 38)

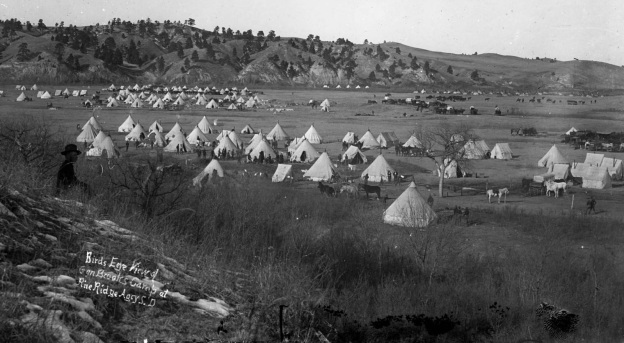

“Birds Eye View of Gen Brooks Camp at Pine Ridge Agcy S. D.” from the Denver Public Library Digital Collections. The view includes the camp of the 2nd U.S. Infantry Regiment.

The command was comfortably fixed in regard to tentage; there were Sibley stoves for all, the weather was simply perfect, and, barring the monotony always attendant upon a permanent camp in the field, the days slipped along pleasantly. There was nothing to interest one but the inhabitants. The country is utterly devoid of game,—no fishing within a radius of twenty miles,—so most of our time was given to taking long tramps and rides over the adjoining country. We were occasionally enlivened by an Indian dance. During my stay there I witnessed one by the women, called a “squaw dance,” and one by the bucks termed the “war dance.” It is my intention to give a description of these in some later paper.

The real cause of the presence of troops in the Indian country was, as we found out later, due to representations of the agent, that the Indians were unmanageable, and indulging in what they called “The Messiah or Ghost Dance.” It is a sort of religious exercise, or dance, kept up for hours, until the participants are thrown into a state of physical and mental frenzy horrible to behold. The agent had tried to stop this dance, but to no purpose, and they were even continued some little time after our arrival at the agency.

The presence of the troops and increased rations soon brought the Indians to their senses, and on the 28th of December the trouble was thought by all to be over; in fact, a portion of my regiment was under orders to return to Fort Omaha, Nebraska, the next day, but the events of the 29th of December really opened the active hostilities. It might be well to quote the report of Dr. McGillicudy, made December 4, 1890, who had been present at the agency for some time as the representative of the governor of South Dakota:

“The condition of affairs when I left there last week was as follows: About four thousand of the agency Indians were camped at the agency. The outlying villages, churches, and schools were abandoned. About two thousand Brules and Wazazas were camped twenty-five miles distant on Wounded Knee Creek, uncertain whether to come into the agency or not, on account of the presence of troops. Emissaries of Sitting Bull were circulating among all of the Indians, inciting them to revolt, and ranging through the abandoned villages, destroying property of friendly Indians. Indians by the dozen were beseeching me to obtain permission for them to go to their homes and protect their property, their horses, cows, pigs, chickens, etc., the accumulation of years. Runners came to me from the Brule camp, asking me to come out and explain what the coming of troops meant. They said they knew me, would believe in me, and come in. Red Cloud and other chiefs made the same request of Agent Royer and Special Agent Cooper. The request was refused; no white man was sent to them. On Sunday last Sitting Bull’s emissaries prevailed; the Brules became hostile, stole horses and cattle, and are now on the edge of the Bad Lands, ready for a winter’s campaign. Many Indians who were friendly when I left the agency will join them. They have possession of the agency beef-herd of thirty-five hundred head of cattle. The presence of troops at the agency is being rapidly justified. What I state, investigation can substantiate.”

This report of Dr. McGillicudy was made on the 4th of December, and by the 26th of the same month, everybody thought the problem had arrived at an amicable solution. Big Foot, with about two hundred or more of his people, had left the Rosebud Agency without permission and was traveling towards the Pine Ridge Agency, South Dakota. He was intercepted by a battalion of the famous Seventh U. S. Cavalry at Wounded Knee Creek, about sixteen miles from Pine Ridge, December 27.

He had been an intimate friend of Sitting Bull; was one of the leaders of the Ghost Dance, and the defiant and belligerent conduct of himself and people had influenced the other Indians heretofore friendly. As soon as his capture was reported, the second battalion of the Seventh Cavalry left to join the first battalion, and the work of disarming the Indians, occurring on the 29th of December, led to the now famous battle of Wounded Knee.

While it is not my intention to write, in detail, of the affair, the following extract from Mr. Herbert Welsh’s article, “The Meaning of the Dakota Outbreak,” in the April Scribner, may not be inapropos:

“Evidence from various reliable sources show very clearly that Colonel Forsythe, the veteran officer in charge, did all that could be done by care, consideration, and firmness to prevent a conflict. He had provided a tent warmed with a Sibley stove for Big Foot, who was ill with pneumonia. He assured the Indians of kind treatment, but told them, also, that they must surrender their arms. He tried to avoid a search for weapons, but to this they forced him to resort. The explosion came during the process of searching, and when a medicine man incited them to resist and appealed to their fanaticism by assuring them that their sacred shirts were bullet-proof. Then one shot was fired by the Indians, and another and another. The Indians were wholly responsible in bringing on the fight.”

There is no doubt that the Indians were incited to resistance by their medicine man, and their belief in his assurances of their ghost shirts being bullet-proof.

The following incident was related to me by the agency interpreter, who was present during the entire engagement. When the firing had entirely ceased, the troops went over the field looking for any wounded they might be of assistance to, whites or Indians. They came to a young buck of splendid physique, but hurt beyond recovery.

“Can we do anything for you?” asked the interpreter.

“Yes, carry me to the medicine man; he lies over there (pointing towards him), so that I may plunge my knife into his heart; do this for me and I die content. He alone is responsible for the many dead and dying spread over this cold, wide battle-field.”

I only give this to show the blind belief these people had in their medicine men before the fight. However, my little sketch deals not with the Wounded Knee affair, but with the events that transpired at the agency the same day. As early as nine o’clock in the morning of the 29th, rumors began to float about camp of an engagement at Wounded Knee between the Seventh Cavalry and Big Foot’s band.

Most of us placed no reliance in the rumor, but we noticed that the Indians were restless, very much excited, and acting strangely. From the direction of Wounded Knee, Indian couriers were coming constantly into camp, and all about could be seen groups of them talking and gesticulating wildly. Things began to assume a serious aspect, but still no authentic news of an engagement. The friendly Indians gathered about and close to our camp, while the majority seemed to be getting their effects together in anticipation of a move.

About eleven o’clock, or, possibly, twelve, official notice of the fight was brought by Lieutenant Guy Preston, of the Ninth Cavalry, who had made the ride from Wounded Knee in an incredibly short time (Immediately upon dismounting, his horse fell dead.); and almost instantly following his arrival, the Indians, principally the Brule Sioux belonging to the bands of Little Wound, Crow Dog, and Big Road, began to leave the agency with their families and ponies.

The alarm was instantly sounded, the companies fell in, fully armed and equipped, and then we awaited developments.

At this time the Second United States Infantry, of eight companies, probably about three hundred and fifty or four hundred men, was the only organization present. The Seventh Cavalry was at Wounded Knee, the Ninth Cavalry was still in the Bad Lands, and the light battery, with the exception of a small detachment and a couple of 3.2-inch guns, was absent with the cavalry commands. In addition to our regiment we could rely on about fifty Indian police and agency employes.

The Indians in and about the vicinity of the agency numbered over three thousand, and under the circumstances it was hard to distinguish friend from foe. And so we waited. The women and children had been gathered together in the agency school-building; the stores were all hurriedly closed, locked, and barred; and what with the handful of soldiers patiently awaiting results, and the Indians moving around excitedly and only wanting an excuse to bring on an engagement, the scene was a rather interesting one.

Red Cloud’s band, camped about half a mile from the school-building, was as yet the only one that had not started; at about one o’clock they began to move, and a few moments later a single shot broke the suspense. Another and another, and then a regular fusillade.

The Indians had attacked the agency.

The companies immediately took the places assigned them, practically covering the four approaches to the agency. The first fire of the hostiles was delivered at the Indian police, and by the time we had gotten to their assistance the firing had ceased and the Indians were circling around on their horses beyond rifle-fire.

The companies were deployed in their respective positions, and then we waited a couple of weary hours. And yet it was not without interest. From our place of deployment we could see the Indians leaving their camps near the agency, clad, or rather unclad, in full war regalia, pieces at an advance, and driving their herds off towards the north. They would have been easy picking, but the order was “No firing.” Indian blood was sacred, and so we saw them ride out within easy rifle-shot, and become full-fledged hostiles, without any opposition on our part.

It was incredible, but it was orders, and so they left in small parties, fully armed and equipped. It was these same Indians that fought the Mission fight of the next day, an action that cost the government the life of “dear Jimmy Mann,” as gallant an officer and gentleman as ever wore spur or steel.

After about an hour’s weary waiting, recall was sounded, and the companies marched back to camp. American Horse, a friendly chief, with his following, had moved near the vacant camp of the Seventh Cavalry, and the other friendly Indians had moved their tepees closer towards our camp. Our rest lasted for only forty or fifty minutes, for after that interval the hostiles resumed the attack, and the companies were again ordered to their respective places.

“B” company had been assigned the north flank of the agency, in the immediate vicinity of the saw-mill, the left of our skirmish-line touching the right of the Indian police. The Indian police had placed logs and timber along the front, affording a good protection from the enemy’s fire. Before reaching this we had quite an open space to pass through, and at the second attack the company was exposed to rather heavy fire. This time we had the misfortune to have three men wounded, not seriously, however. In this connection a rather remarkable case of presentiment or coincidence occurred that came under my personal observation. At the first fire of the Indians upon the agency, one of the members of the company, an old soldier and a man who had served through the greater part of the Rebellion, turned to the man next to him (the company being deployed as skirmishers) and said, “Well, this is hard luck, only six more days to serve; I’d look well with an Indian bullet in me.” Strangely enough, he was the first man wounded. (The sad and sudden death of Captain William Mills, one of the senior and ablest officers of the regiment, was the only other casualty. He was found dead in his tent on the morning of the 30th of December, an apparent case of heart-disease.)

The fire was kept up for some time, but the Indians were so far away that their bullets fell short. They moved off slowly, firing and circling about on their ponies, and then for the second time that day withdrew, but the work of the soldiers was far from over. “A” company of the regiment was sent out to intrench one of the neighboring hills, and “B” company was given the pleasant occupation of guarding the north flank, the position they had occupied during the day’s work. The company was divided into two squads. The first remained on duty until 3 o’clock A.M., the morning of the 30th, and the second squad from that time until breakfast, about 6.30 or 7 o’clock A.M. It was a beautiful night, clear and bright. The heavens were studded with stars, and the big cold moon sailed overhead, looking down with pity upon the handful of men stretched along the little skirmish-line. At 8.30 P.M. we received the welcome news of the arrival of the Seventh Cavalry from Wounded Knee, and half an hour later the ambulances and wagons came rumbling into camp, filled with the dead and dying. The dead and wounded soldiers were carried into the field hospital, and the wounded Indians into the Episcopal Church (a small frame building) and a Sibley tent, about two hundred yards in rear of our skirmish-lines. I was present on duty when the wounded Indians were unloaded from the wagons and carried to the tent. It was a sight never to be forgotten, and one not pleasant to dwell upon. After this excitement had subsided, the camp settled into quietude but watchfulness. The minutes dragged along into hours, and yet the Indians gave no sign. There had been a great deal of talk about their firing the agency; but hour after hour passed, and the only noises that disturbed the silence of the night was the steady tramp of the sentinel, and the occasional howl of some Indian dog that had been left behind. Soon the stars began to pale and fade from sight, the air grew colder, and a long gray streak in the east told us that the night was over.

Thomas H. Wilson,

First Lieutenant Second U. S. Infantry.

Lieutenant Wilson recorded that there were three casualties in the regiment that day. A review of Colonel Frank Wheaton’s post return for that month lists the regiment’s wounded, which included two from Wilson’s company.

On December 29, 1890, the Camp at Pine Ridge Agency, S. D. was attacked by hostile Indians and the following men of this Battalion were wounded:

Private Robert Gruner, Co. B, 2d Infantry

Private Thomas Haran, Co. B, 2d Infantry

Private Charles Miller, Co. H, 2d Infantry

The reporter for the Omaha Bee that recorded Lieutenant Kinzie’s reflection had a different accounting of wounded soldiers from the regiment, “The wounded men who were to be brought in [to Omaha] were Lieutenant John Kinzie, adjutant of the Second infantry; Corporals Boyle and Cowley, Company G, and Privates Hahn, Haran and Gruner, Company B, all of the Second infantry.” The Bee correspondent included several soldiers who were returned to Fort Omaha for other ailments. He went on to record of Private Gruner:

Gruner was seen by a Bee reporter, to whom he stated that his wound had not troubled him at all since the preceding night. He was shot through the thigh at the time the attack was made on the agency Monday afternoon. The company was double timing in sets of fours to form a skirmish line when he was shot. The bullet was a 45-caliber Winchester, and struck the man in front of him, in precisely the same place, passing through his leg and then hitting Gruner. The ball passed through Gruner’s leg and made a flesh wound in the leg of the man behind him. The last wound was not serious. These were the only soldiers hurt in the attack. When the men were started home, they had to ride the twenty-six miles from Pine Ridge to Rushville in an ambulance. This was anything but pleasant for a wounded man, and then to make matters worse they had to lie in Rushville for seven hours waiting for their train, which did not leave until 1 o’clock.

Private Gruner certainly was the wounded soldier who Lieutenant Wilson quoted as saying, “Well, this is hard luck, only six more days to serve; I’d look well with an Indian bullet in me.” The Bee reporter went on to write of Gruner and the other ailing soldiers:

“My term is up next Friday,” said Gruner, “and I want to re-enlist so as to get a little satisfaction for this job.”

This is the third time that Gruner has been wounded. The first time was during the rebellion at the battle of Red river, and the second time during the Modoc war.

Haran, who was wounded at the same time as Gruner, was hurt considerably worse, the ball having gone through the thickest part of his leg, making him lame. He was suffering severely after his long trip.

Corporal Boyle was suffering from rheumatism and Corporal Cowley and Private Hahn had each a high fever.

The only fatality in the 2nd Infantry during the campaign also came sometime during the evening of the 29th and the morning of the 30th of December at the agency. Lieutenant Wilson mentions Captain William Mills’s death briefly in a footnote. In his monthly post return, Colonel Wheaton recorded the passing of his most senior company commander, “Returned to duty from Sick in Qrs., Dec. 3, ’90. Died at Pine Ridge Agency, S. D. from ‘Heart Failure’ at about 3. a.m., Dec. 30, 1890.” Captain Mills, a fifty-four-year-old Michigander, like Lieutenant Wilson, had risen from the ranks. He enlisted in 1858 in the 5th Infantry and rose to be the first sergeant of Company C by 1862. Mills served for a year as an acting second lieutenant in the regiment until receiving a commission to that rank in the 16th U.S. Infantry. He was promoted to captain in the regular army in 1866 and transferred to the 2nd Infantry in 1869, the regiment with which he served for the next two decades. At the time of his death Captain Mills had been married for sixteen years to Sarah Jane McQuhae, a Pennsylvania native who claimed Elmira, New York, as her home. They had two children, fourteen-year-old Anna and twelve-year-old William junior. The Omaha Daily Bee ran two articles detailing Captain Mills’s passing, the first of these appearing under the title “Sleeps His Last Sleep,” which ran the day after the captain’s demise.

The unpleasant news received Monday from Pine ridge was intensified yesterday with the intelligence that will cause a great deal of sorrow at the firesides in the military homes at Fort Omaha. It was the announcement of the death of Captain William Mills, Company C, Second infantry, located in this city.

The news was telegraphed by Lieutenant Rowell, who, it is supposed, was acting regimental adjutant, during the probable incapacity of Lieutenant Kinzie, who, it has been announced, was wounded Monday in the fight with Big Foot’s gang on Porcupine Creek.

The intelligence occasioned a shock at Fort Omaha, and especially in the home of the deceased, where a widow and two children inconsolably mourn his demise.

Captain Mills was a brave and capable officer and he looked the soldier as well as he knew how to act as one. He was of a genial companionable disposition, readily adapted himself to every circumstance and made friends in civil as well as in military life. Of all the gallant officers and men who formed the first detachment of the Second infantry, which was called into the field on that night early in November, Captain Mills looked least like the one who was first to die. Although he had complained shortly before of a slight indisposition, he was the picture of health and his martial bearing at the head of the column was one of the picturesque features of that march to the train. Death resulted from rheumatism of the heart which was doubtless occasioned by exposure. Captain Mills had shortly before his departure for the field been summoned before the examining board at Leavenworth for promotion to which he was entitled by long and arduous service.

Captain Mills was born in Michigan, September 19, 1836. He was appointed from the army and served successively as private, sergeant and first sergeant of company C, Fifth infantry from October 28, 1858, to February 23, 1863; he was acting second lieutenant Fifth infantry from January 6, 1862 to February 23, 1863; also second lieutenant Sixteenth infantry and was promoted to the office of captain February 13, 1866. On April 17, 1869, he was transferred to the Second infantry.

On account of his gallant and meritorious services during the Atlanta campaign and in the battle of Jonesboro, Ga., he was breveted captain September 1, 1864. During the civil war, he held staff positions as follows: Aid-de-camp of volunteers from October 2 to November 1, 1864, and from October 12, 1865 to February 13, 1866, was regimental quartermaster of the sixteenth infantry.

It is not known where he will be buried.

The second article, which detailed Captain Mills’s funeral cortege at Fort Omaha, was titled “The Fort in Mourning,” and ran 5 January 1891.

Sorrow seemed to pervade the air in the vicinity of Fort Omaha yesterday, and instead of the soldiers being happy, as is their wont, they were bowed down with grief. They had been called upon to pay the last tribute to a commander and comrade, Captain William Mills.

Shortly after 10 o’clock the officers of the garrison, followed by the few privates who have not been sent to the front, passed through the large hall in the hospital building, where for the last time they gazed upon the remains of the gallant officer, as they rested in the elegant metallic casket.

There were no funeral exercises, no military pomp and splendor, but many a tear was dropped upon the coffin containing the body of the man who looked as peaceful and natural as though his eyes were closed in sleep instead of in death. The casket was closed and about it was wrapped the flag that Captain Mills loved so dearly. After this the pall bearers, Alber Wedemeyer, chief musician; John Kennaman principal musician; John Stahl, first sergeant of company A; John Forbes, sergeant of company D; Thomas H. Mooney, corporal of company H, and James Ping, corporal of company E, tenderly lifted the coffin of the soldier from its place and with bared heads bore it from the building to the ambulance that was in waiting outside.

Around the wagon were thirty-four soldiers, forming a guard. The procession slowly wended its way through the parade grounds and to the union depot, from whence the remains were sent last night, going to Elmira, N. Y., for interment.

Source: Thomas H. Wilson, “The Attack on the Pine Ridge Indian Agency, S. D.: An Unwritten Chapter,” from The United Service, A Monthly Review of Military and Naval Affairs vol. 7 (Philadelphia: L. R. Hamersly & Co., 1892), 562-568.

Citation for this article: “2nd Infantry at the Pine Ridge Agency,” Army at Wounded Knee (Sumter, SC: Russell Martial Research, 2013-2015, http://wp.me/p3NoJy-D4), updated 29 December 2014, accessed date __________.

Very interesting as well.

Regards

Susan

Sent from my iPad

>

LikeLike

I have a Mills 1888 Infantry cartridge belt that is marked, “H” “2” “35” and it has a luminol-verified bloodstain on the center-back running from the top down. If Private Charles Miller, Co. H was wounded during the attack at Pine Ridge as Lt. Wilson noted, there is a strong possibility that the belt was his.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fascinating. Do you know the provenance of the belt? Would you care to share a picture?

LikeLike