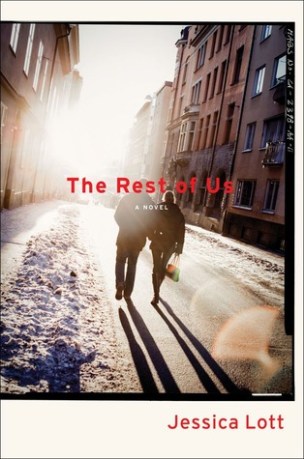

The Rest of Us

By Jessica Lott

Simon & Schuster, 2013

289 pages

If there’s one thing I’ve noticed among the books I’ve read in the last few years, it’s that the quality of debut novels just seems to keep getting better and better. Of course, we never really know how long this “young” (or at least new) author worked on their first published novel, or how many previous novels have been written and scrapped or simply never found a publisher. Whatever the circumstances, contemporary readers usually don’t need to worry about whether an author’s first novel is likely to be mature, polished, insightful, and the like.

Jessica Lott’s first novel (she previously published a novella, Osin), The Rest of Us, reads like the work of a much more experienced writer. She displays two traits in particular that I found to be convincing evidence of her true talent: she digs very deeply into her main character’s inner life and she never writes an awkward, clunky, or unclear sentence. (To be fair, some credit must also go to her editor, Anjali Singh.)

The Rest of Us captures the lives of two people who are very different, and yet both are struggling with their art and their personal life. It’s the story of 34-year-old photographer Terry, whose life has been derailed into an emotional and professional ditch since the relationship she began as a 19-year-old college student with her poetry professor ended badly nearly 15 years earlier. In this first-person narrative, Terry takes us back to her college days in upstate New York and the development and dissolution of her May-December relationship with Rudolf Rhinehart (known throughout the novel simply as Rhinehart). They meet at an artist lecture in town a few months before Rhinehart joins the faculty at Terry’s university. Terry acknowledges early on that, “If I hadn’t been in the grip of some sort of magical thinking, I would have recognized that he was in his forties, nearing the height of his career, and a professor. I would have been intimidated, rightly…. I told myself, I’ll just try and get to know him better…. We did become friends, but by then I felt we should be together and said so. He had discovered that I was a college student and was reluctant. I plowed ahead, too confident in the connection between us to be dissuaded, and in the end I was right.”

The first part of the book details the vicissitudes of their year-long affair, and Lott deserves credit for making the characters of Terry and Rhinehart, and their relationship, intense yet believable. Terry is smarter, more mature, and more creative than many of her classmates, and Rhinehart is eventually taken with her. But the relationship ends up on the rocks of Terry’s neediness and Rhinehart’s role as a Pulitzer Prize-winning poet and well-known cultural intellectual.

Back to the present and 34-year-old Terry is adrift. She is still living in the same apartment since her college days, she works as the assistant to a photographer, and she has long been single. Her promising artistic career has gone nowhere, but for several years she hardly noticed. But now, in a more introspective phase, she wonders, “How could it have come to this? Why hadn’t I gotten further by now? Why was I still struggling alone with no one to help me or even to share my life? I thought angrily of Rhinehart, and then, despairingly, about myself and my inability to progress.”

An unusual series of events brings Terry and Rhinehart back into each other’s lives. She is excited to see him again but wary of reconnecting with him; he reaches out to her in a manner that suggests he views her only as a long-lost friend. He is remarried and seemingly secure in reestablishing Terry’s acquaintance after so long. Her best friend since college, Hallie, tries to warn her away from trying to recapture a past that was never as good as Terry believed then (and believes now). But she proceeds despite Hallie’s advice.

Rhinehart is experiencing his own emotional and professional struggles. He tells Terry, “I stopped writing well after the Pulitzer. I spent two years furiously composing, only to throw most of it away, then more time sitting blankly, looking at the wall, wondering what the point of anything was. That feeling grew into a creeping fear that grew into aversion.” Not surprisingly, their second attempt at a relationship is fraught. During one tense conversation in her new apartment — she’d been inspired to make a change — she thinks, “I had a weird sensation of time suspended before us, stretching out in all directions, like a flat, dark sea, and this couch a little rowboat that we were snugly on, drifting.” She knows the relationship has again gone off course, but she is at a loss for how to navigate to a safe harbor.

But Rhinehart’s reentry into Terry’s life recharges her artistic impulses, and she begins to rediscover her creative vision as a photographer. Rhinehart’s wife, a gallery owner, takes a mysterious interest in Terry and invites her to openings, where she introduces her to other artists and key gallery owners. Terry’s career begins to gather steam, while Rhinehart’s is stalled. Lott, who writes for Art 21 and frequently writes essays for the New York Times and other arts publications, clearly knows the art world inside out.

Some readers have commented, on sites like Good Reads and Amazon, that the last portion of The Rest of Us falls victim to plot contrivances. While that may arguably be true, Lott maintains control of the narrative as it moves toward its dramatic conclusion, and the story continued to hold my interest. Late in the book, Terry thinks, “In this chaotic procession of events, accidental encounters, and fears that I’d struggled with, there had been an invisible plan. I was experiencing the rightness of my life, all of it, and it felt like lightning had hit me. I was trying to convey this, then I stopped and said, ‘How do you feel?’… He said, ‘I guess we both knew less about how our lives were going to turn out than we thought.'”

I enjoyed The Rest of Us largely for its depiction of a complex intimate relationship and the way people think and feel when they are falling in and out of love. “When I was younger, I’d felt Rhinehart hadn’t loved me as much as I loved him. Our relationship and its changing moods had bled all over my life — I thought about him in class, at parties, while studying. For him, the concept of us was so neatly packaged, something he could slide away into a desk with many small drawers. It was a quality that had seemed to empower him.”

While Terry and Rhinehart are not the most sympathetic or charming people, they are realistic, flawed human beings — the most interesting kind — and I was interested to see what would grow out of their roles in each other’s lives. Their complicated relationship and inner lives always intrigued me and created sufficient narrative momentum to carry me to the surprising conclusion. Lott is clearly a young writer to watch, and I look forward to her next book eagerly.