Cohn comments on the new Commonwealth Fund report I highlighted earlier today:

The Congressional Budget Office predicted that, one year into full implementation, Obamacare would reduce the number of Americans without insurance by twelve million. That included the young adults who got insurance before 2014, by signing onto their parents’ plans. There’s been some controversy over exactly how many more young people are insured because of that new option, but the best estimates I’ve seen place the number somewhere between 1 and 2.5 million. Add that number to the 9.5 million from the Commonwealth survey, and you’re close or equal to the CBO projections.

Of course, the Commonwealth survey has a hefty margin of error and the CBO projections, revised to take account of the early technological problems on Obamacare websites, were never that scientific. But the figures seem to be in the same ballpark. That’s what matters.

Douthat isn’t ready to declare Obamacare a success:

[I]f the Commonwealth figure is right we’re probably looking at between 10 and 11 million newly-insured overall for 2014 (I’m relying on “best estimates” for the number of young adults that are slightly lower than Cohn’s), which is lower than the 12 million the C.B.O. projected in April, which is lower than the 13 million it projected after the website problems, which is lower than the 14 million it projected after the Supreme Court decision on Medicaid, which is lower … you get the idea.

All of which means that this new estimate, while useful, doesn’t really bring us any closer to knowing whether Obamacare enrollment will ultimately end up where its advocates hoped — making up ground lost during the disastrous roll-out over the next couple of years, and hitting 25-30 million newly insured by 2017 or so — or whether its current shortfalls will persist and it will end up many millions below that target.

Sanger-Katz focuses on how “people who got the new coverage were generally happy with the product”:

Overall, 73 percent of people who bought health plans and 87 percent of those who signed up for Medicaid said they were somewhat or very satisfied with their new health insurance. Seventy-four percent of newly insured Republicans liked their plans. Even 77 percent of people who had insurance before — including members of the much-publicized group whose plans got canceled last year — were happy with their new coverage.

Kliff points to other details:

About four in ten Obamacare enrollees reported having signed up for Obamacare say they chose a narrow network plan, with lower premiums — but also fewer doctors and hospitals. This explains why just over one third (37 percent) say that all of the doctors they wanted were part of their insurance plan’s network. It’s possible that number could be an underestimate, as 39 percent said they weren’t sure which doctors were and weren’t included.

At the same time, subscribers who did see a doctor generally reported being able to schedule appointments pretty quickly. Most were able to get an appointment within two weeks.

On a less happy note, Flavelle finds that blacks are faring relatively poorly under Obamacare:

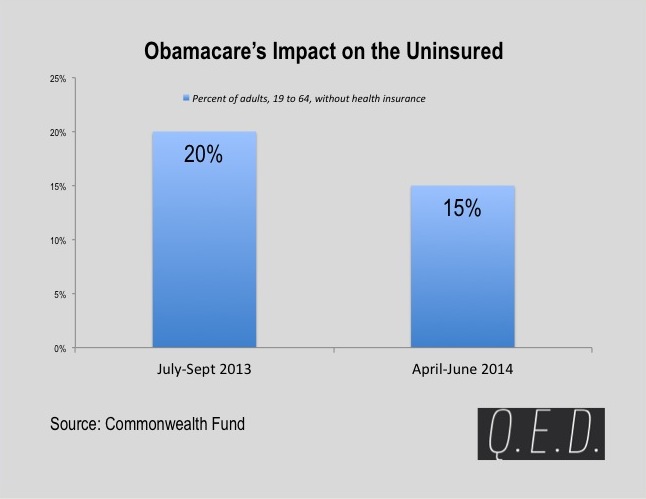

The uninsurance rate for whites fell to 12 percent from 16 percent; for Latinos, it plummeted, to 23 percent from 36 percent. For respondents who reported their race as “mixed” or “other,” the share without insurance was cut almost in half, to 11 percent from 20 percent. The exception to that trend was blacks. When the Commonwealth Fund conducted a survey from July to September last year, 21 percent of blacks reported being uninsured. This year, in a similar survey conducted from April to June, that level was effectively unchanged, at 20 percent.

Why?

A big part of the explanation, without question, is that a disproportionate share of blacks live in states that have so far refused federal money to expand Medicaid. Sixty-two percent of black respondents fall into that category, compared with just 39 percent of Latinos.