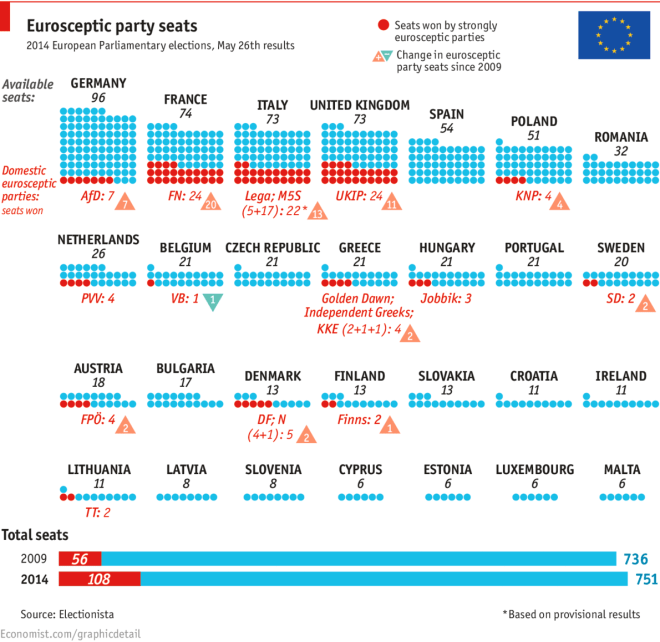

The Economist charts the results of the European parliamentary elections:

Douglas Elliott downplays the Euroskeptic party gains:

This could have been a lot worse and I do not agree with some of the analysis that uses terms such as “earthquake” to describe the result. I do not see the outcome as fundamentally reshaping the political situation in Europe and it seems very likely that this is the high water mark for the protests parties. The next such election in five years should be in a considerably more favorable environment for Europe, cutting down the protest votes sharply. In the meantime, European Parliament votes generally do not carry over to national elections where voters are much more careful about who they hand power to. Further, two of the countries where the protest votes were largest, the UK and France, have different rules for national elections that make it much harder for protest parties to win seats than in the European Parliament elections.

Yglesias strikes a similar tone:

In practice, the increased vote share for far-right (and to a lesser extent far-left) parties will make very little difference. The [European People’s Party ‘s] candidate, former Luxembourg Prime Minister Jean-Claude Juncker will very likely form a Commission composed of members of mainstream parties of both the left and the right, with the center-right in the driver’s seat — exactly the situation that has prevailed since 2004.

But Desmond Lachman argues that “significance of the European parliamentary elections cannot be overestimated”:

The rise of the National Front in France has to raise questions about the continued effectiveness of the Franco-German machine that has been central to Europe’s move to greater economic and political integration. The rise of UKIP in the United Kingdom is all too likely to harden David Cameron’s stance in negotiations with Brussels on returning authority to London ahead of the promised 2017 referendum as to whether the United Kingdom should remain in the Union. Meanwhile, the rise of Syriza is bound to make it increasingly difficult for the Greek government to continue with budget austerity and economic reform so necessary to get the Greek economy moving again.

It would be a grave mistake for European policymakers to dismiss the strong vote for an assortment of anti-European parties as merely a protest vote at an election with no great significance.

Tracy McNicoll sees Marine Le Pen as the big winner:

Looking more closely, far-right Euroskeptical parties’ results were mixed. The Austrian Freedom Party (FPÖ), which saw one top candidate forced to step down last month after likening EU regulations to Nazi Germany, finished third nationally but topped 20 percent of the vote. Geert Wilders’ Dutch Party for Freedom (PVV), which some polls tipped to win, finished third in the Netherlands, losing one of its five seats. And Belgium’s Vlaams Belang also lost ground.

But one far-right performance easily eclipsed the rest. France’s Marine Le Pen, 45, quadrupled her party’s 2009 score. With 24.83 percent nationally, the National Front will hold a third of France’s seats in Strasbourg with 24 seats, up from three. Both Le Pens, Marine and 85-year-old Jean-Marie, won reelection. And Jean-Marie Le Pen’s blond scion looks to be just getting into her stride.

Tim Wigmore feels “perspective is needed” on UKIP’s strong showing:

Ukip came top, yes, but with 27.5% – and in an election in which turnout was a derisory 35%, 30% less than in the last general election. This “political earthquake” may yet do no more than mildly shake the cutlery. If Nigel Farage is serious about getting Ukip seats at the next general election, he will soon have to upset a lot of prominent party personnel. The party lacks the resources to target more than a dozen seats in 2015.

And Matt Ford reflects on Europe’s democratic deficit:

[T]he massive election comes at a time when the disconnect between the EU and the people it governs has arguably never been greater. A Pew Research poll this month found that majorities in seven major European countries think their voice doesn’t count in the EU, including 81 percent of Italians and 80 percent of Greeks. The European Union itself acknowledges the popular perception that EU bodies “suffer from a lack of democracy and seem inaccessible to the ordinary citizen because their method of operating is so complex.” It’s what the institution and many others call a “democratic deficit.”

Here’s the paradox, though: When given the chance to elect members of the European Parliament, fewer Europeans are taking the opportunity to make their voices heard than ever before.