I’m convinced that 80% or more of our disagreements would be settled if we could first agree on the definitions of our words. If we could agree on the terms we’re using, countless implications would flow from that common starting point.

I’m convinced that 80% or more of our disagreements would be settled if we could first agree on the definitions of our words. If we could agree on the terms we’re using, countless implications would flow from that common starting point.

In this post, we’re going to try to somehow define “honor.” We’ll consider “shame” in the next post. I use the word “define” loosely. I really prefer “to generally describe” honor. Westerners love definitions because we can then start dividing categories and decide what’s in and what’s out.

I’ve written extensively about this in my book Saving God’s Face. So, if you want a bit more of an explanation and its application for theology and missions, check out the book.

“HONOR”

I think it’s best to start in broadest terms: one’s honor is essentially one’s value according to some public standard. Whatever you say about someone being honor or having honored, it will someway or another involve how they are regarded by some group of people. At some level, it is inherently public.

One’s group becomes the standard by which one measures his or her worth or respect. One may be honored for various reasons. Some are intrinsically moral (showing courage or loyalty). Other causes of honor are more neutral or trivial––like one’s fashion sense, cool blog, or writing skill.

It’s pretty common for people to distinguished ways of getting honor. It can either be ascribed or achieved. One might be ascribed honor according to his or her family, birth, position, gender, etc. Achieved honor refers to that which comes through individual accomplishments, like grades in school or winning a gold medal.

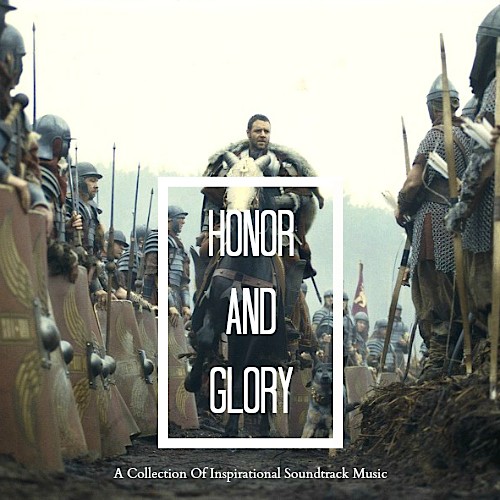

“GLORY”

In the Bible, honor is functionally equivalent to glory.

Now, I have expended much effort trying to make this point to Westerners. Finally, one day I spend multiple hours in a theological library photocopying nearly every theological and anthropological source that addressed this question (dictionaries, monograph, commentaries, articles). The next day I took a rather thick and convincing stack of papers to that group confirming scholarly consensus on this point. To glorify someone, to get glory, to have glory is to honor someone, to get honor, or to have honor (in one sense of the word). Therefore, when we are talking about God’s glory, we are talking about his honor . . . his worth which should and ultimately will be recognized in all the universe.

One more thing to note: Honor and shame are more that mere subjective or relativistic categories. However, I’ll hold off on that point until we talk about shame. For now, keep in mind that the Christian indeed gets honor from God even while he may be spurned by his own family, clan, colleagues, or classmates. However, that sort of contrast misses the point that the honor ascribed to the Christian only comes in the context of belonging to God’s people.

Whose Honor and Glory?

The Church’s standard of honor derives from God’s own character. When we follow Christ, we exchange our honor standard, what we measure as valuable and right. We join a new community. The Christian’s honor comes through identification with God’s people, whose head is Christ. To show loyalty to Christ entail showing loyalty to his people.

Loyalty is inherently public.

To show loyalty to God’s family necessitates one embrace its own measure of honor. On the other hand, this will also mean enduring the shame heaped on it by the world who lives by an entirely different view of honor and shame.

So as not to rewrite my book here, I’ll stop here. Click here for Part 1 of the series.

I’ve listed some relevant books for thought (like The Hope of Glory). I’ll elaborate on shame in the next post.

Related articles

- The Biblical Story in the Context of Honor and Shame (www.patheos.com/blogs/jacksonwu)

- Is Our Theology Enslaved to the Law? (www.patheos.com/blogs/jacksonwu)

- A Model to Explain the Entire Bible (a new series) (www.patheos.com/blogs/jacksonwu)

- Biblical Theology from a Chinese Perspective (www.patheos.com/blogs/jacksonwu)