Joseph Yesurun Pinto, a 31 year-old Anglo-Dutch émigré in the autumn of 1760, had led New York’s Shearith Israel synagogue for barely a year when the second notice appeared in the papers. To re-commemorate the British conquest of Canada, all “Christian societies” and “houses of worship” would celebrate a day of thanksgiving on Thursday, October 23d. Over the past decade, New Englanders and their neighbors had held at least 50 fast days, many to lament God’s judgments against America, or to reform their wayward behavior. The proclamation of a thanksgiving day likely brought some measure of relief and joy.

Joseph Yesurun Pinto, a 31 year-old Anglo-Dutch émigré in the autumn of 1760, had led New York’s Shearith Israel synagogue for barely a year when the second notice appeared in the papers. To re-commemorate the British conquest of Canada, all “Christian societies” and “houses of worship” would celebrate a day of thanksgiving on Thursday, October 23d. Over the past decade, New Englanders and their neighbors had held at least 50 fast days, many to lament God’s judgments against America, or to reform their wayward behavior. The proclamation of a thanksgiving day likely brought some measure of relief and joy.

Like his Christian colleagues, Pinto fashioned a liturgy that featured psalm singing and a pair of lectures to honor God for preserving King George II’s dominions. Pinto consulted with rabbis in London. Carefully, he crosschecked the Church of England’s newly released form of prayer. The prescribed Gospel text was Matthew 5:43, reminding colonists to love their enemies and endure persecution while en route to eternal reward. The prayer language was less peaceable, praising the fierce wind and water that God steered to favor “his” Britons. “It is not our own Strength that hath saved,” the suggested prayer read, “but thou hast maintained our Right and our Cause.” Several years’ worth of fast days seemed fulfilled, and another part of God’s plan for the new Israel was locked into place. Throughout the fall, a general air of thanksgiving (quite literally) echoed beyond Pinto’s congregation and other dutiful meetinghouses. Between Sundays, American laity sang along to John Playford’s popular tune on the “reduction” of the Canadian dominions: “With Feasting and Thanksgiving / our grateful Hearts are fed; / Which gratifies the Living / And can’t offend the dead.”

My current research is on fast and thanksgiving days like these, social rituals that I think generated opportunities for multi-religious participation within, first, the expanding British empire, and, later, the broadening marketplace of faiths in independent America. In local fits of ingenuity, religious leaders like Pinto made intriguing adaptations to the rite. And, in reading the related proclamations and sermons, these days emerge as contested rites, forming a bygone cultural arena where clergy, politicians, and laity collaborated and clashed on how to mold “American” character. Acts of special worship offer evidence of one of American religion’s most distinctive characteristics: the overlapping cultural authority forged by an uneasy local hybrid of church and state. New England ministers, in particular, deployed the old Puritan fast day to exert moral influence over civil magistrates. The laity were equally fervent, using it as a joint plea to Providence if they decided that their ministers had stumbled as God’s messengers. They held fasts at sea and in the ashes of burned churches. More than once, they even threatened to keep fasting if new clergy dragged their feet in salary negotiations. In Connecticut, parishioners seized the initiative, toggling from a scheduled fast to an impromptu thanksgiving, when a drought ended earlier than predicted.

My current research is on fast and thanksgiving days like these, social rituals that I think generated opportunities for multi-religious participation within, first, the expanding British empire, and, later, the broadening marketplace of faiths in independent America. In local fits of ingenuity, religious leaders like Pinto made intriguing adaptations to the rite. And, in reading the related proclamations and sermons, these days emerge as contested rites, forming a bygone cultural arena where clergy, politicians, and laity collaborated and clashed on how to mold “American” character. Acts of special worship offer evidence of one of American religion’s most distinctive characteristics: the overlapping cultural authority forged by an uneasy local hybrid of church and state. New England ministers, in particular, deployed the old Puritan fast day to exert moral influence over civil magistrates. The laity were equally fervent, using it as a joint plea to Providence if they decided that their ministers had stumbled as God’s messengers. They held fasts at sea and in the ashes of burned churches. More than once, they even threatened to keep fasting if new clergy dragged their feet in salary negotiations. In Connecticut, parishioners seized the initiative, toggling from a scheduled fast to an impromptu thanksgiving, when a drought ended earlier than predicted.

Long before the more familiar Victorian manifestation of Thanksgiving as a family feast, the early Americans who celebrated days of thanksgiving found that they did so while navigating serious currents of cultural and political turbulence. The half-forgotten rituals of fast and thanksgiving days—often relegated to “supporting actor” status in surveys of early American life—were key sites where laity experimented with the inheritance of English faith, and brought New World religion to bear on public issues. Between the end of the 17th century and the onset of Revolution, American ministers used these days to criticize local authority, regulate social morality, and reinterpret the colonies’ significance in God’s government. While it is important to see why colonists like Pinto prayed for their king, I began this project to understand what else they prayed for. I am equally curious about the American religious “instinct” to take ownership of the ritual. Why did they practice “national” payer long before America took real shape, and how did those processes intersect?

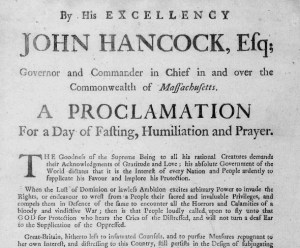

Word of a fast or feast day (generally on Tuesday or Thursday) came by proclamation three weeks to a month prior. With labor banned, the daily duties of farming and industry came to a full stop. Most adherents went to meetinghouse, heard two sermons, sang psalms, and refrained from eating until after the second service. Mourning one’s sins and scriptural reflection took up the rest of the day. A well-known minister like Ezra Stiles or Mather Byles, Jr. often supplied the phrasing for a governor’s call. Standard proclamation language announced either a “day of solemn humiliation, fasting and prayer” or one of “publick thanksgiving.” Bearing the royal arms and a colonial seal, the double-column proclamations were, at first, handwritten on paper ranging from 8” x 12” to 15” x 20.” By 1670, Massachusetts and Connecticut changed over to printed versions, far easier to publicize. Another century on, and Massachusetts revolutionaries edited “God Save the King” to read “God Save the People.” They were supposed to read the proclamation in the pulpit before leading prayer, but by the beginning of the 19th century many clergy read it with disdain or skipped it entirely. Other preachers issued sharp jeremiads on the sinful overreach of mortal (read: political) authority in matters divine. There were penalties, too, threatened to those who flouted the call. Such was the case of Quaker Samuel Stapleton, who told a Rhode Island court that he was “above observing” such days and times. They let him go with a small fine.

Word of a fast or feast day (generally on Tuesday or Thursday) came by proclamation three weeks to a month prior. With labor banned, the daily duties of farming and industry came to a full stop. Most adherents went to meetinghouse, heard two sermons, sang psalms, and refrained from eating until after the second service. Mourning one’s sins and scriptural reflection took up the rest of the day. A well-known minister like Ezra Stiles or Mather Byles, Jr. often supplied the phrasing for a governor’s call. Standard proclamation language announced either a “day of solemn humiliation, fasting and prayer” or one of “publick thanksgiving.” Bearing the royal arms and a colonial seal, the double-column proclamations were, at first, handwritten on paper ranging from 8” x 12” to 15” x 20.” By 1670, Massachusetts and Connecticut changed over to printed versions, far easier to publicize. Another century on, and Massachusetts revolutionaries edited “God Save the King” to read “God Save the People.” They were supposed to read the proclamation in the pulpit before leading prayer, but by the beginning of the 19th century many clergy read it with disdain or skipped it entirely. Other preachers issued sharp jeremiads on the sinful overreach of mortal (read: political) authority in matters divine. There were penalties, too, threatened to those who flouted the call. Such was the case of Quaker Samuel Stapleton, who told a Rhode Island court that he was “above observing” such days and times. They let him go with a small fine.

Fast and feast days functioned as a cultural “place” for Americans to consider how they related to authorities civil and divine. For clergy, a proclamation presented duty and opportunity. Educated mainly at Harvard or Yale, young ministers knew that the tradition had roots in Jewish Ingathering, and in the keeping of the Feasts of Christ. For the small-town New Englander Samuel Woodward, a decade into the pastorate that paid him £26 a year plus firewood, the good news from Canada meant another sermon to draft amid artillery elections and Sunday catechisms. A young Congregationalist weighing the leap to Anglicanism, Mather Byles, Jr., saw in the Connecticut call to thanksgiving a chance to boost the royal cause—and thereby raise his own profile. Ezra Stiles, who doubled as the Newport librarian, set aside his research on the lost tribes of Israel in order to cast a critical eye on the British victory. “We are planting an empire with better laws and religion” than that of Europe, Stiles instructed Rhode Islanders. If God’s divine favor were to extend beyond Britain, then colonists hoped to call attention to America’s displays of piety.

Local days of special worship framed the colonists’ struggle to read God’s will in their lives, cementing a religious practice that lasted well into the 19th century. Waves of pox, “an army of caterpillars” that blasted wheat crops, and a series of earthquakes made God’s displeasure feel very close, and very real. From Cotton Mather to John Quincy Adams (or, from Puritan to Unitarian), Americans believed that like a storm, these afflictions held purifying effects. Days of prayer refreshed the “unsettled soul.” When he sat down to compose the proclamation, a governor openly pledged his community to Christianity, whether he asked all of Boston, Massachusetts, or New England to pray. When a minister answered in a sermon accepting the latest “fiery trial”—drought, pests, Indian massacres—he framed religious solutions to renew America’s covenant with God. This “national” prayer—held long before the colonies threaded together any sense of nationhood beyond British rule—fostered Christian union, spiritual confidence, and even a hazy religious pluralism at the inter-colonial level. Cotton Mather’s sound bites and Joseph Pinto’s liturgical innovations should be read again, then, and in fuller context. The routine construction of colonial religion, glimpsed here at the daily level, held big consequences for Americans’ struggle to balance duties to God and government. To a degree, celebrating fast and thanksgiving days readied those same colonists-turned-nationalists to face the modernizing world, and each other.

Local days of special worship framed the colonists’ struggle to read God’s will in their lives, cementing a religious practice that lasted well into the 19th century. Waves of pox, “an army of caterpillars” that blasted wheat crops, and a series of earthquakes made God’s displeasure feel very close, and very real. From Cotton Mather to John Quincy Adams (or, from Puritan to Unitarian), Americans believed that like a storm, these afflictions held purifying effects. Days of prayer refreshed the “unsettled soul.” When he sat down to compose the proclamation, a governor openly pledged his community to Christianity, whether he asked all of Boston, Massachusetts, or New England to pray. When a minister answered in a sermon accepting the latest “fiery trial”—drought, pests, Indian massacres—he framed religious solutions to renew America’s covenant with God. This “national” prayer—held long before the colonies threaded together any sense of nationhood beyond British rule—fostered Christian union, spiritual confidence, and even a hazy religious pluralism at the inter-colonial level. Cotton Mather’s sound bites and Joseph Pinto’s liturgical innovations should be read again, then, and in fuller context. The routine construction of colonial religion, glimpsed here at the daily level, held big consequences for Americans’ struggle to balance duties to God and government. To a degree, celebrating fast and thanksgiving days readied those same colonists-turned-nationalists to face the modernizing world, and each other.

As a colonialist, I’m well acquainted with days of thanksgiving and fasting and understood their civic contexts but I’d never thought of their interdenominational context. Absolutely fantastic piece!

And Happy Thanksgiving to all of The Junto‘s readers!!

Pingback: The Garrisoned Heart | s-usih.org

Pingback: Begging for Bounty « The Junto