Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

THINKING–AND THE TURK

HOW DO WE think? In these days of artificial intelligence, not to say unexpected political outcomes, this question is a non-trivial one. A new book on this, and more, is discussed in the London Review of Books, December 1, 2016.

The Restless Clock: A History of the Centuries-Long Argument over What Makes Living Things Tick, by Jessica Riskin, University of Chicago Press, 2016.

Steven Shapin’s LRB review, “More than Machines,” of Jessica Riskin’s The Restless Clock mentions mathematicians of note, Rene Descartes and Gottfried Wilheim Leibnitz; Benjamin Franklin; Edgar Allan Poe; and The Turk. It is with this last one that I find special resonance today.

Riskin’s book starts with “medieval ideas about machines and animals; it goes on to discuss the mechanical philosophies of the Scientific Revolution; the automata crazes of the Enlightenment; the tensions of 18th and 19th century life science over design… and it finishes with discussions of cybernetics, robots and artificial intelligence.”

Quite a sweep, and what caught my eye was the mention of automata, mechanical devices that moved with human-like actions. Notes reviewer Shapin, “The Catholic Church was the main patron of the ‘great bustling population’ of automata that ‘thronged the landscape of late medieval and early modern Europe.’ ”

Author Riskin cites mechanical Christs on the cross, bowing, shaking and rolling their eyes in agony; the crowing mechanical rooster on top of the great clock of the Three Kings in Strasbourg Cathedral; angelic automata carrying saintly souls to their reward; and a mechanical Assumption of the Virgin–Mary blissfully hoisted up to heaven by an “endless screw.” Clever Archimedean engineering there.

French mathematician René Descartes, 1596–1650, is honored today in Cartesian coordinates, the xy plane and xyz three-dimensional graphical systems. Riskin writes that Descartes was especially impressed by automata of complex hydraulics, “a single motive power–the flow of water,” which could give life-like “agency” to a machine.

By contrast, German mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibnitz, 1646–1716, co-discoverer of calculus, framed his philosophical musings of thought and perception in terms of clockwork. Shapin observes that the Leibnitz clock “wasn’t merely an inanimate metaphor for animate things but was itself animate.” Said another way, “machines were more than machines.”

And so it was with The Turk, a chess-playing automaton constructed in 1770. Wolfgang von Kempelen, 1734–1804, was a Hungarian author and inventor, fluent in German, Latin, French, Italian, his native Hungarian and, eventually English and Romanian. He was also something of a con man.

Von Kempelen first exhibited The Turk to Empress Maria Theresa of Austria at her Schönbrunn Palace in Vienna. The Turk had a life-size head and torso, was dressed in Turkish robes and turban, and sat at an oversize cabinet with a chessboard atop it.

The cabinet’s front had three doors, behind which were complex assemblies of gears, cogs, levers and whatnot. With any one of the front doors open, another door at the rear permitted seeing through the machine. The Turk’s robes could be adjusted to reveal other clockwork machinery.

In playing chess, The Turk would nod twice when threatening his opponent’s Queen and three times when putting the opponent’s King into check. If the opponent made an illegal move, The Turk would shake his head and move the errant piece back. In time, he acquired an ability to utter ”échec!” French for “check.”

Von Kempelen toured Europe with The Turk in the 1780s, though he claimed to have other projects he found more interesting. The Turk demonstrated considerable prowess at chess, usually winning against even skilled opponents. His final game in Paris was against Benjamin Franklin, U.S. ambassador to France at the time, who took an interest in the machine. Eventually, The Turk returned to Schönbrunn Palace, where he resided until von Kempelen’s death in 1804.

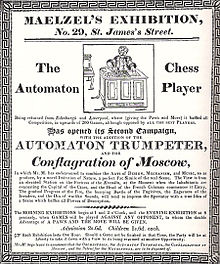

Von Kempelin’s son sold The Turk to Johann Nepomuk Mälzel, a Bavarian musician with an interest in automata. Mälzel refurbished The Turk and hosted a game with Napoleon I at Schönbrunn Palace in 1809. There are contradictory stories about the match. One, for example, suggests that Napoleon attempted an illegal move more than once, and The Turk responded by knocking all the pieces off the board with a sweep of his arm. Napoleon was said to have been amused.

The Turk and Mälzel visited Milan, Munich, Paris and London, followed by a tour of the U.K. In 1826, they played the U.S., with visits to New York, Boston (which allegedly had better opponents…), Philadelphia, Baltimore and other venues west. In Richmond, Virginia, Edgar Allan Poe’s interest in The Turk led to an essay, Maezel’s Chess Player.

Mälzel’s last tour was to Havana, Cuba. He died at sea on his return to Europe in 1838. The Turk was left with the ship captain and passed subsequently through the hands of other entrepreneurs. The Turk’s last words, a repeated ”echec! echec!” occurred when a fire destroyed a Baltimore museum, his residence in 1854.

This tale sounds wonderfully poignant until you realize that The Turk was a con, with a human chess player artfully lodged within during the matches. What’s more, throughout The Turk’s career, plenty of people, including Ben Franklin and Edgar Allan Poe, suspected the ruse.

Can this be today’s teachable moment? ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2016

Information

This entry was posted on December 18, 2016 by simanaitissays in And Furthermore... and tagged "The Restless Clock: A History of the Centuries-Long Argument of What Makes Living Things Tick" Jessica Riskin, automata, Benjamin Franklin, Edgar Allan Poe, Johann Nepomuk Malzel, London Review of Books, Napoleon I, The Turk chess-playing machine, Wolfgang von Kempelen.Shortlink

https://wp.me/p2ETap-5lfCategories

Recent Posts

Archives

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012