Simanaitis Says

On cars, old, new and future; science & technology; vintage airplanes, computer flight simulation of them; Sherlockiana; our English language; travel; and other stuff

ROARING TWENTIES

IT’S NO wonder the 1920s acquired the name Roaring Twenties. It’s certainly warranted from an economic point of view. A recent piece, “The Myth of Gatsby’s Suffering Middle Class,” by Amity Shlaes in The New York Times, June 2, 2013, puts this in perspective. I’ll offer some of its data here, with some amplification of my own.

Shlaes notes that, true, the rich did get richer during the 1920s—but so did the rest of American society. This is particularly so relative to their own expectations and with things we think of as essentials. In 1920, for example, only 20 percent of American households had indoor flush toilets. By 1930, more than half did.

The Electrical Association for Women was one early organization celebrating electrification of the home. Image from The Institute of Engineering and Technology, www.theiet.org.

In 1920, only 35 percent of American homes had electricity, these, mostly in cities. By 1930, this grew to 68 percent. Today, less than 1 percent of Americans are off the grid, a percentage of these, by choice.

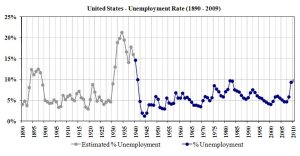

The 1920s began with widespread joblessness, but before long unemployment dropped below 5 percent—and stayed below this figure for much of the decade. By contrast, of late we’ve been hovering around 7.5 percent.

The workweek improved during the 1920s. Prior to that, many Americans worked a six-day week. A scathing comment comes to mind concerning Andrew Carnegie, who worked his people 12 hours a day, six days a week—and then gave them libraries to enjoy in their spare time.

Productivity grew with machines and mass production, and workers profited from this. In 1914, Ford famously doubled his workers’ minimum wage to $5/day—and cut their hours from nine to eight, albeit still six days a week.

With advanced technology came enhanced productivity—and the potential of a shorter workweek. Image, the Ford Model T production line.

Shlaes notes that “In 1920, scholars surveyed companies and found only 32 had cut back to five-day workweeks.” Ford moved to five days in 1926; by 1927, 262 large companies had given employees a new concept: free Saturdays.

It wasn’t until 1938 that changes in the workweek went nationwide through provisions of the Fair Labor Standards Act. Even then, it affected only about one-fifth of the labor force. In fact, the per capita workweek in the U.S. actually increased by 20 percent between 1970 and 2002.

Back to the 1920s: Ford’s goal of his workers affording the product of their labor also came to fruition during this time. In 1920, only around 25 percent of American households had cars. By 1930, this rose to more than 50 percent.

During the 1920s, Model T Fords comprised more than half the cars in the world.

It’s estimated that today more than 89 percent of American households have a car, although not all Fords. ds

© Dennis Simanaitis, SimanaitisSays.com, 2013