Oh the drama! Some of the current hyperventilating in the alternative nutrition community–sugar is toxic, insulin is evil, vegetable oils give you cancer, and running will kill you–has, much to my dismay, made the alternative nutrition community sound as shrill and crazed as the mainstream nutrition one.

When you have self-appointed nutrition experts food writers like Mark Bittman agreeing feverishly with a pediatric endocrinologist with years of clinical experience like Robert Lustig, we’ve crossed over into some weird nutrition Twilight Zone where fact, fantasy, and hype all swirl together in one giant twitter feed of incoherence meant, I think, to send us into a dark corner where we can do nothing but nibble on organic kale, mumble incoherently about inflammation and phytates, and await the zombie apocalypse.

No, carbohydrates are not evil—that’s right, not even sugar. If sugar were rat poison, one trip to the county fair in 4th grade would have killed me with a cotton candy overdose. Neither is insulin, now characterized as the serial killer of hormones (try explaining that to a person with type 1 diabetes).

But that doesn’t mean that 35 years of dietary advice to increase our grain and cereal consumption, while decreasing our fat and saturated fat consumption has been a good idea.

I have gotten rather tired of seeing this graph used as a central rationale for arguing that the changes in total carbohydrate intake over the past 30 years have not contributed to the rising rates of obesity.

The argument takes shapes on 2 fronts:

1) We ate 500 grams of carbohydrate per day in 1909 and 500 grams in 1997 and WE WEREN’T FAT IN 1909!

2) The other part of the argument is that the TYPE of carbohydrate has shifted over time. In 1909, we ate healthy, fiber-filled unrefined and unprocessed types of carbohydrates. Not like now.

Okay, let’s take closer look at that paper, shall we? And then let’s look at what really matters: the context.

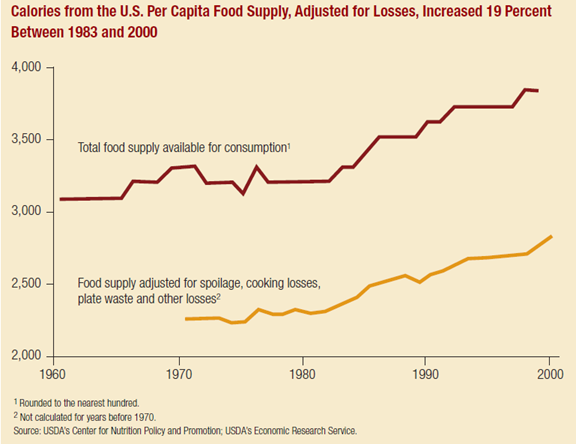

The data used to make this graph are not consumption data, but food availability data. This is problematic in that it tells us how much of a nutrient was available in the food supply in any given year, but does not account for food waste, spoilage, and other losses. And in America, we currently waste a lot of food.

According to the USDA, we currently lose over 1000 calories in our food supply–calories that don’t make it into our mouths. Did we waste the same percentage of our food supply across the entire century? Truth is, we don’t know and we are not likely to find out—but I seriously doubt it. My mother and both my grandmothers—with memories of war and rationing fresh in their minds—would be no more likely to throw out anything remotely edible as they would be to do the Macarena. My mother has been known to put random bits of leftover food in soups, sloppy joes, and—famously—pancake batter. To this day, should your hand begin to move toward the compost bucket with a tablespoon of mashed potatoes scraped from the plate of a grandchild shedding cold virus like it was last week’s fashion, she will throw herself in front of the bucket and shriek, “NOOOOOO! Don’t throw that OUT! I’ll have that for lunch tomorrow.”

You know what this means folks: in 1909, we were likely eating MORE carbohydrate than we are today. (Or maybe in 1909, all those steelworkers pulling 12 hour days 7 days a week, just tossed out their sandwich crusts rather than eat them. It could happen.)

BUT–as with butts all over America including mine, it’s a really Big BUT: How do I explain the fact that Americans were eating GIANT STEAMING HEAPS OF CARBOHYDRATES back in 1909—and yet, and yet—they were NOT FAT!!??!!

Okay. Y’know. I’m up for this one. Not only is problematic to the point of absurdity to compare food availability data from the early 1900s to our current food system, life in general was a little different back then. At the turn of the century,

- average life expectancy was around 50

- the nation had 8,000 cars

- and about 10 miles of paved roads.

In 1909, neither assembly lines nor the Titanic had happened yet.

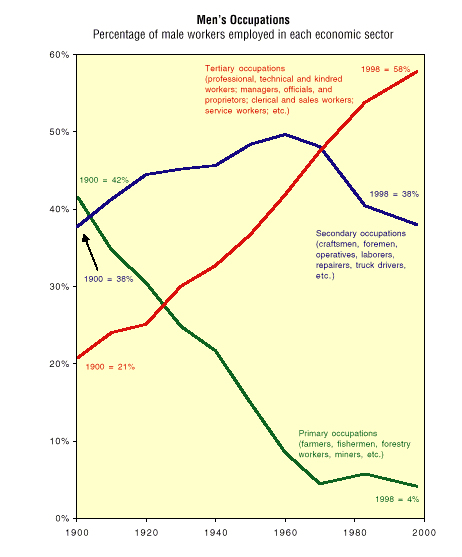

The labor force looked a little different too:

Primary occupations made up the largest percentage of male workers (42%)—farmers, fisherman, miners, etc.—what we would now call manual laborers. Another 21% were “blue collar” jobs, craftsmen, machine operators, and laborers whose activities in those early days of the Industrial Revolution, before many things became mechanized, must have required a considerable amount of energy. And not only was the work hard, there was a lot of it. At the turn of the century, the average workweek was 59 hours, or close to 6 10-hour days. And it wasn’t just men working. As our country shifted from a rural agrarian economy to a more urban industrialized one, women and children worked both on the farms and in the factories.

This is what is called “context.”

In the past, nutrition epidemiologists have always considered caloric intake to be a surrogate marker for activity level. To quote Walter Willett himself:

“Indeed, in most instances total energy intake can be interpreted as a crude measure of physical activity . . . ” (in: Willett, Walter. Nutritional Epidemiology. Oxford University Press, 1998, p. 276).

It makes perfect sense that Americans would have a lot of carbohydrate and calories in their food supply in 1909. Carbohydrates have been—and still are—a cheap source of energy to fuel the working masses. But it makes little sense to compare the carbohydrate intake of the labor force of 1909 to the labor force of 1997, as in the graph at the beginning of this post (remember the beginning of this post?).

After decades of decline, carbohydrate availability experienced a little upturn from the mid 1960s to the late 1970s, when it began to climb rapidly. But generally speaking, carbohydrate intake was lower during that time than at any point previously.

I’m not crazy about food availability data, but to be consistent with the graph at the top of the page, here it is.

Data based on per capita quantities of food available for consumption:

| 1909 | 1975 | Change | |

| Total calories | 3500 | 3100 | -400 |

| Carbohydrate calories | 2008 | 1592 | -416 |

| Protein calories | 404 | 372 | -32 |

| Total fat calories | 1098 | 1260 | +162 |

| Saturated fat (grams) | 52 | 47 | -5 |

| Mono- and polyunsaturated fat (grams) | 540 | 738 | +198 |

| Fiber (grams) | 29 | 20 | -9 |

To me, it looks pretty much like it should with regard to context. As our country went from pre- and early industrialized conditions to a fully-industrialized country of suburbs and station wagons, we were less active in 1970 than we were in 1909, so we consumed fewer calories. The calories we gave up were ones from the cheap sources of energy—carbohydrates—that would have been most readily available in the economy of a still-developing nation. Instead, we ate more fat.

We can’t separate out “added fats” from “naturally-present fats” from this data, but if we use saturated fat vs. mono- and polyunsaturated fats as proxies for animal fats vs. vegetable oils (yes, I know that animal fats have lots of mono- and polyunsaturated fats, but alas, such are the limitations of the dataset), then it looks like Americans were making use of the soybean oil that was beginning to be manufactured in abundance during the 1950s and 1960s and was making its way into our food supply. (During this time, heart disease mortality was decreasing, an effect likely due more to warnings about the hazards of smoking, which began in earnest in 1964, than to dietary changes; although availability of unsaturated fats went up, that of saturated fats did not really go down.)

As for all those “healthy” carbohydrates that we were eating before we started getting fat? Using fiber as a proxy for level of “refinement” (as in the graph at the beginning of this post—remember the beginning of this post?), we seemed to be eating more refined carbohydrates in 1975 than in 1909—and yet, the obesity crisis was still yet a gleam in Walter Willett’s eyes.

While our lives in 1909 differed greatly from our current environment, our lives in the 1970s were not all that much different than they are now. I remember. As much as it pains me to confess this, I was there. I wore bell bottoms. I had a bike with a banana seat (used primarily for trips to the candy store to buy Pixie Straws). I did macramé. My parents had desk jobs, as did most adults I knew. No adult I knew “exercised” until we got new neighbors next door. I remember the first time our new next-door neighbor jogged around the block. My brothers and sister and I plastered our faces to the picture window in the living room to scream with excitement every time she ran by; it was no less bizarre than watching a bear ride a unicycle.

In 1970, more men had white-collar than blue-collar jobs; jobs that primarily consisted of manual labor had reached their nadir. Children were largely excluded from the labor force, and women, like men, had moved from farm and factory jobs to more white (or pink) collar work. The data on this is not great (in the 1970s, we hadn’t gotten that excited about exercise yet) but our best approximation is that about 35% of adults–one of whom was my neighbor–exercised regularly, with “regularly” defined as “20 minutes at least 3 days a week” of moderately intense exercise. (Compare this definition, a total of 60 minutes a week, to the current recommendation, more than double that amount, of 150 minutes a week.)

Not too long ago, the 2000 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (DGAC) recognized that environmental context—such as the difference between America in 1909 and America in 1970—might lead to or warrant dietary differences:

“There has been a long-standing belief among experts in nutrition that low-fat diets are most conducive to overall health. This belief is based on epidemiological evidence that countries in which very low fat diets are consumed have a relatively low prevalence of coronary heart disease, obesity, and some forms of cancer. For example, low rates of coronary heart disease have been observed in parts of the Far East where intakes of fat traditionally have been very low. However, populations in these countries tend to be rural, consume a limited variety of food, and have a high energy expenditure from manual labor. Therefore, the specific contribution of low-fat diets to low rates of chronic disease remains uncertain. Particularly germane is the question of whether a low-fat diet would benefit the American population, which is largely urban and sedentary and has a wide choice of foods.” [emphasis mine – although whether our population in 2000 was largely “sedentary” is arguable]

The 2000 DGAC goes on to say:

“The metabolic changes that accompany a marked reduction in fat intake could predispose to coronary heart disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus. For example, reducing the percentage of dietary fat to 20 percent of calories can induce a serum lipoprotein pattern called atherogenic dyslipidemia, which is characterized by elevated triglycerides, small-dense LDL, and low high-density lipoproteins (HDL). This lipoprotein pattern apparently predisposes to coronary heart disease. This blood lipid response to a high-carbohydrate diet was observed earlier and has been confirmed repeatedly. Consumption of high-carbohydrate diets also can produce an enhanced post-prandial response in glucose and insulin concentrations. In persons with insulin resistance, this response could predispose to type 2 diabetes mellitus.

The committee further held the concern that the previous priority given to a “low-fat intake” may lead people to believe that, as long as fat intake is low, the diet will be entirely healthful. This belief could engender an overconsumption of total calories in the form of carbohydrate, resulting in the adverse metabolic consequences of high carbohydrate diets. Further, the possibility that overconsumption of carbohydrate may contribute to obesity cannot be ignored. The committee noted reports that an increasing prevalence of obesity in the United States has corresponded roughly with an absolute increase in carbohydrate consumption.” [emphasis mine]

Hmmmm. Okay, folks, that was in 2000—THIRTEEN years ago. If the DGAC was concerned about increases in carbohydrate intake—absolute carbohydrate intake, not just sugars, but sugars and starches—13 years ago, how come nothing has changed in our federal nutrition policy since then?

I’m not going to blame you if your eyes glaze over during this next part, as I get down and geeky on you with some Dietary Guidelines backstory:

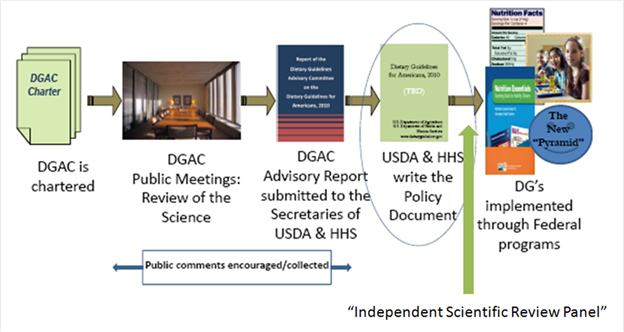

As with all versions of the Dietary Guidelines after 1980, the 2000 edition was based on a report submitted by the DGAC which indicated what changes should be made from the previous version of the Guidelines. And, as will all previous versions after 1980, the changes in the 2000 Dietary Guidelines were taken almost word-for-word from the suggestions given by the scientists on the DGAC, with few changes made by USDA or HHS staff. Although HHS and USDA took turns administrating the creation of the Guidelines, in 2000, no staff members from either agency were indicated as contributing to the writing of the final Guidelines.

But after those comments in 2000 about carbohydrates, things changed.

Beginning with the 2005 Dietary Guidelines, HHS and USDA staff members are in charge of writing the Guidelines, which are no longer considered to be a scientific document whose audience is the American public, but a policy document whose audience is nutrition educators, health professionals, and policymakers. Why and under whose direction this change took place is unknown.

The Dietary Guidelines process doesn’t have a lot of law holding it up. Most of what happens in regard to the Guidelines is a matter of bureaucracy, decision-making that takes place within USDA and HHS that is not handled by elected representatives but by government employees.

However, there is one mandate of importance: the National Nutrition Monitoring and Related Research Act of 1990, Public Law 445, 101st Cong., 2nd sess. (October 22, 1990), section 301. (P.L. 101-445) requires that “The information and guidelines contained in each report required under paragraph shall be based on the preponderance of the scientific and medical knowledge which is current at the time the report is prepared.”

The 2000 Dietary Guidelines were (at least theoretically) scientifically accurate because scientists were writing them. But beginning in 2005, the Dietary Guidelines document recognizes the contributions of an “Independent Scientific Review Panel who peer reviewed the recommendations of the document to ensure they were based on a preponderance of scientific evidence.” [To read the whole sordid story of the “Independent Scientific Review Panel,” which appears to neither be “independent” nor to “peer-review” the Guidelines, check out Healthy Nation Coalition’s Freedom of Information Act results.] Long story short: we don’t know who–if anyone–is making sure the Guidelines are based on a complete and current review of the science.

Did HHS and USDA not like the direction that it looked like the Guidelines were going to take–with all that crazy talk about too many carbohydrates – and therefore made sure the scientists on the DGAC were farther removed from the process of creating them?

Hmmmmm again.

Dr. Janet King, chairwoman of the 2005 DGAC had this to say, after her tenure creating the Guidelines was over: “Evidence has begun to accumulate suggesting that a lower intake of carbohydrate may be better for cardiovascular health.”

Dr. Joanne Slavin, a member of the 2010 DGAC had this to say, after her tenure creating the Guidelines was over: “I believe fat needs to go higher and carbs need to go down,” and “It is overall carbohydrate, not just sugar. Just to take sugar out is not going to have any impact on public health.”

It looks like, at least in 2005 and 2010, some well-respected scientists (respected well enough to make it onto the DGAC) thought that—in the context of our current environment—maybe our continuing advice to Americans to eat more carbohydrate and less fat wasn’t such a good idea.

I think it is at about this point that I begin to hear the wailing and gnashing of teeth of those who don’t think Americans ever followed this advice to begin with, because—goodness knows—if we had, we wouldn’t be so darn FAT!

So did Americans follow the advice handed out in those early dietary recommendations? Or did Solid Fats and Added Sugars (SoFAS—as the USDA/HHS like to call them—as in “get up offa yur SoFAS and work your fatty acids off”) made us the giant tubs of lard that we are just as the USDA/HHS says they did?

Stay tuned for the next episode of As the Calories Churn, when I attempt to settle those questions once and for all. And you’ll hear a big yellow blob with stick legs named Timer say, “I hanker for a hunk of–a slab or slice or chunk of–I hanker for a hunk of cheese!”

When looking at the past and (assuming) people ate a great deal more fiber-based carbohydrates — which is to say, whatever they were eating, it was far less processed, both seed-genetically and as a manufactured food-like ingestible entertainment product, as I call most so-called food today — there are some important confounding factors I think get forgotten along with this, such as:

Since one must assume they were eating (gasp) ‘real food,’ then:

1. There is also ‘vitamins and minerals’ change between then and now (ref: Weston Price), which is to say that we didn’t just get ‘more fiber back then’ we also got more vitamins and minerals from the foods that fiber was in.

2. There is also ‘enzyme’ change between then and now (due to the dramatic shift in nonlocal, picked green, bred for shipping produce). So we now get a lot less of that as well.

3. There is also a substantial agricultural increase in herbicides. So now we get a lot more of that toxin as well.

4. There is also a substantial agriculture increase in pesticides. So now we get a lot more of that as well.

So even if we ate the SAME amount of fiber today, now compared to then we would still get significantly less vitamins, less minerals, more toxic pesticides, more toxic herbicides. Oh yeah… and more fiber.

I point this out in case the article gives anyone the idea that fiber is some kind of savior. I can’t comment on that, though I seriously doubt it, but I can say that what the change over time indicates, implies much more than just the fiber itself.

Thanks for chiming in! All good points. In 1977, the additional herbicide/pesticide burden was one of the concerns that was raised when the initial Dietary Goals were being created.

The decrease in fiber between “now” and “then” is just not that dramatic. And if you eat a Fiber One bar, especially on a long car trip in the company of people you wish to not offend, you may find out why “added fiber” may not be a savior for some folks. Not that I would know anything about that.

“manufactured food-like ingestible entertainment product”

Phrase of the Day!

Yet another insight into the banana seat mythos:

http://fitisafeministissue.wordpress.com/2013/04/05/bike-seats-speed-and-sexual-depravity/

And what is not to love about that? Thanks so much for sharing that link.

Glad you liked it!

The US had all its fat presidents before WW1.

http://mentalfloss.com/article/51449/last-words-and-final-moments-38-presidents

The real obesity epidemic was over before the records began, judging by these photos

I suspect that says more about wealth, class, and social norms than anything else. Judging the rest of America by the person in the White House is a bit of a skewed perspective, but it’s a fascinating link.

You might like this, from NZ academic Dr Andrew Dickson (who usually posts at othersideofweightloss.org and is well worth checking out)

http://masseyblogs.ac.nz/othersideofbusiness/2013/01/24/the-demise-of-the-fat-capitalist/

My husband and I were discussing this recently. If the current crop of powerbrokers is using the eat less/move more approach to being slim and trim (easier done when you have the financial resources, significant willpower, and intense social pressure to make it work), then there may be even less sympathy, understanding, or willingness to consider that this approach may not work for everyone. Sigh.

And I’m not sure that shifting the paradigm from an “eat less fat” to an “eat fewer carbs” paradigm will really change the inclination of those who are successful (in weight maintenance, as well as other walks of life) to insist that their way is THE way: http://observer.com/2013/06/geoffrey-miller-fat-shaming-tweet-nyu/

How interesting that in 1909 the world wasn’t yet flushing toilets, polluting food and water supply with flora-shifting sewage. Activated sludge was invented in 1913. It’s no accident the most obese nations are least sanitary, defecating directly in drinking water for generations. It’s no better here in the developed world of flushing toilets; arguably worse as we multiply the wrong kinds of microbes in the name of sanitation. It’s these shifts in flora where carbs feed microbial overgrowth leading to obesity, diabetes . . . my favorite part was your mom blocking the compost bucket, riotous!!

Well, as interesting as this angle is, sanitation on its own wouldn’t explain the change in the slope of the obesity curve that happened after 1977-1980. But combined with the change in dietary recommendaitons? Hmmm, perhaps. Recognizing that obesity and diabetes (and other chronic diseases) have multiple, intertwined complex etiologies, change in gut flora seems to be part of that puzzle.

This makes me want to take AHS posts out of my feed. Terrible writing. Heavy straw-manning. Very little positive argument. Boring.

Don’t harsh on AHS cuz of me. I’m boring and terrible all on my own–ask my children. Look around. I’m sure you can find someone in the AHS crowd who better supports whatever views you’ve already determined to be correct.

And on this blog site, we’re all about “straw-womaning,” thank you very much.

Don’t know why my comments didn’t make it through. I only wanted to add that in 1909 people held much more food animals for personal consumption (or even hunted, trapped and fished much more) than nowadays and these high quality food sources would not be visible in the food statistics from the state. People today are much more dependent for their food sources than in older times, which means that the official recommendation will have a much higher impact than it had even in the 60s.

I don’t know either, unless you commonly post as sex.dating@hotmail.com or maybe you were the one letting me know about “A little bit loose, additional costly, and additionally oftentimes even more, effectively, colorful, all the folks’ economy is normally which you could pick-up some container with regard to browsing, a new xylophone made out of your berries material and a few copper mineral tubes, as well as a 15-minute massage therapy just about all concurrently.”

You are very right about all of this. It is really sort of dopey to even attempt to write a coherent blog post addressing comparisons between food availability data from 1909 to 1997, but it’s been raining a lot here, so it was either blog or vacuum the house. I PROMISE my next post will address some of the differences in our food system and food environment in general pre/post dietary recommendations.

It was probably on my side that something went wrong. I had also the children that were nagging when I wrote the comments so it could be that I mis-clicked. It’s unfortunate as there were other points and anecdotes I made about the change in cookware, animal husbandery and unaccounted for foods in older times. Next time I will be more attentive.

As for the comment, I wasn’t criticizing you at all but the people that would bring up the comparisons from 1909 and 1997 like Stephan Guyenet who did it several times.

Well, it’s okay to criticize me too 🙂 But, yes, my overwhelming weariness at seeing that graph and that data trotted out time and time again is what prompted the whole thing.

I think it likely that in 1909 the poorest 10% of the country ate less energy and protein (relative to their needs) than their counterparts today, and the richest 10% ate more energy and protein than their modern counterparts. The distribution of consumption across the population was different, so totals are misleading.

I agree. Using aggregate data can be misleading even now. But I remember writing about that elsewhere and I’m not sure why I failed to include that in this post. Thanks for the correction.

Forgive me but I don’t know what this article is trying to say. It is obvious that we DO have an obesity problem now, and the Paleo and Ancestral Health movements are providing an incredibly healthy alternative that is proven to cure obesity. Yes I said “cure obesity”. They are talking about the effects of refined sugar, industrially produced vegetable oils, refined carbohydrates, meats full of hormones, high fructose corn syrup, and a culture thats uses excessive cardio-vascular excersise to mitigate bad diets. If this is dramatic then maybe it needs to be – people are dying from the consumption of processed foods and of malnutrition accross the Western World. It is seriously compromising the life experience of many people. and crucially, a growing number of children. I’m 34 and fully responsible for what I eat. Eight year-olds are not. Processed foods are highly profitable and very unhealthy. This is a bad combination. We need some drama. I am having a full artistic strop right now.

The leaders in this field: Mark Sisson, Rob Wolf, Loren Cordain, Paul Jaminet, amongst others, are entirely objective in their approach, even if the power of natural foods is often only demonstrable by anecdotal evidence. Nature does know better than we do, and always will – we cannot demostrate in a laborotary why natural foods are better for health than processed foods because ultimately, we just don’t know why. Nature made human beings and we still don’t know how it did that either.

We can demonstrate certian aspects of nutritional science in a lab, but I only have a likely 70-80 years’ worth of eating food, I’m not about to wait for establishment science to guide me, they haven’t been doing very well thus far. However where there is some science to be applied, the Paleo movement for me stands out an an exemplar of the objective search for truth in healthy nutrition. Where people to have to retract ideas and views, they do so with humility and grace. Being healthy usually allows you to do this.

PS, if you’ve read someone stating that insulin is evil, they are unlikely to be speaking at the Ancestral Health symposium 2013

http://www.ancestryfoundation.org/ahs13.html

I guess what my article was “trying” say is that issues are not black and white. Carbs are not “bad” and fat is not “good.” The issues are far more nuanced than that. I simply have no data to illustrate that a huge increase in refined sugar consumption from the 1970s to the present is at the root of our current health crisis. Vegetable oils, on the other hand? Yeah, you may have a point there.

I’m glad that you can say with assurance that the leaders in this field are “entirely objective” in their approach; I am unfortunately all too aware of instances where concerns about one’s own personal funding streams interfere with efforts to make an impact on public health, which is always where my concern primarily lies. I’m not sure, but I generally think that those folks who have the time, inclination, and resources to read my blog–or explore paleo lifestyle choices–are probably already pretty capable of handling their own nutrition and health issues. I want to know how we can change the world. I am not yet convinced that the paleo world is committed to that challenge outside of its own ability to make a living from that change. (No this is not a personal slag on any of the people you mentioned; I’ve met all of them and I admire the work they do.)

On the other hand, I am a HUGE fan of the AHS, but I make a clear distinction between them and “paleo.” As its name implied, AHS has what is to me an appropriate focus on the generational impacts of nutrition and lifestyle changes–both past and future. I am also appreciative of the fact that with the term “ancestral” I don’t have to go all the way back to cavemen to examine changes in environment, habits, sleep, and food and how they may have impacted health.

I agree it is so crazy to speak of bad fat or bad carbs. There are such a range of various fats. And you know the sat. fat they feed rats in experiments is some unhealthy processed things. And then carbs get more complicated by the day, as I discovered reading this blog http://digestivehealthinstitute.org/2013/05/resistant-starch-friend-or-foe/

Thanks for the link. Nutrition is complicated–but also very simple. You need essential nutrition first. From lightly, minimally, or traditionally processed foods first. We need to help build that foundation for everyone first. And then, for those who are interested, as many of us are, or have the time and resources, as many of us have, or need additional nutrition support/intervention, as many of us do, we can go on to delve into the complexities. But OVER-simplifying the issue–good or bad, this or that–doesn’t get us there either.

Kris, it is always a pleasure to hear from you and hear about your work!

From my own experience, it was industry propaganda that, for example, convinced me that canola oil was good. My degree was in public health, but it was industry provided materials that colored my thinking. I have the feeling that Ancel Key’s notions about fat wouldn’t have gotten very far if industry wasn’t taking advantage of them to promote their processed food products, and funding the lousy research that supported them. And then, just like doctors, dietitians get brainwashed into thinking they are the experts who know all the answers, so they stubbornly refuse to be open to different ideas. Anyone who reads “The Oiling of America” will be shocked at how they’ve been conned! At least it certinaly turned me around.

You can expect a future blog post to go into some of those tangled relationships. You are very right about industry building on the backs of premature and weak science promoted by public health advocates (and Keys certainly was one)–but then doesn’t it make it even more crucial that the scientific and public health community be exceptionally circumspect about what they say science supports?

I have found that the AHS and paleo movements are very much interchangeable, with peripheral differences and a large collaborative ethos – is that not your expereince?

Not at all. It’s like comparing vegan and vegetarian movements. While there are many similarities, there are some very important differences that–imho–will matter tremendously in the long run. Beginning with, where’s the “ancestral health” book?

You have to understand that I live in a world where the word “paleo” gets approximately the same reaction as the word “Atkins.” There have been far too many people overstating the case for paleo (as happened with Atkins) for it to be a viable term for serious academic and health policy considerations. The vegans figured out that the word “vegan” got a knee-jerk reaction to what was perceived as an extremist point of view and have been content to stand in the shadow of the term “vegetarian”–for better or worse–because it works better in terms of messaging (the exception being the folks who trade on the term “vegan” because they know exactly the crowd that they are marketing their message to). When folks who consider themselves as having a “paleo” approach (but who are not themselves part of the funding stream that requires such branding efforts) begin to shift away from the use of that term to the more neutral one of “ancestral health” then considerations that are encompassed with both approaches will stand a much better chance of making a lasting impact on public health. This is exactly what happened with vegan–> vegetarian and is happening with Atkins –> reduced-carbohydrate.

I have to say that in the long run, I don’t really care what people who have the time, energy, resources, and interest to fiddle about with their diet eat. I care what the public health world is going to do to work with the folks who don’t. And I can assure you that the phrase “paleo” is not going to make it into the public health lexicon.

Good point, Adele! Unfortunately the public health establishment is going to have to change a lot of their favorite beliefs if they are really going to have an impact on public health – raw milk, organic foods, germs, processed food, eggs – the list is endless of instances where they are barking up the wrong tree.

I agree, but I think that the paradigm shift is going to be different from what many of us expect/want. In other words, we are not going to–nor should we–replace the current one-size-fits-all framework with another, different–albeit in our opinion, better–one. We are going to have to learn how to “think different” about nutrition.

Hey Adele, great read. 🙂

My wife and I have been eating a Paleo style diet for around 3 years after a diagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis had us reeling and looking for drug free options. This was preceded by some time spent on a low fat, almost vegan diet that allowed fish (I know). There was no restriction on carbs or anything else but it was very much real food focused and suggested removal of all fats where possible allowing only 15g of extra virgin olive oil per day.

That diet seemed to work for us to some extent with regards to the MS but it did not tackle another issue which was my wife’s tendency to crash after eating carbs. She would get the shakes and have to eat something sugary to get her back on track.

So, as I read more and more we found links to diabetes were common with people with MS and one autoimmune disease soon runs into another and we stumbled across another MS diet known as the Best Bet Diet. This was, although I did not really know it at the time, a Paleo style diet that restricted grains (and therefore carbs but not explicitly) and focused on meat, vegetables and fruit. Again, a real food diet that really focused on the removal of processed foods / oils etc.

So, a standard Paleo template with lean meats and fish, oily fish, vegetables and fruit worked well for us and it seemed that as we removed more carbs and added more fats that the hunger issues and shakes and what I deemed likely to be the early, early signs of diabetes slowly got better.

Other issues such as gum problems and some odd symptoms (hot feet) that she had had all of her life also cleared up. We also found that if there was exposure to grains or dairy there would be MS symptoms that were pretty much non existent at this point. There would also be other odd symptoms after exposure to these foods such as knee pain, gas & bloating and most common of all fatigue.

So, as time went on, we started to eat more and more fat, less fish, lots of bacon, chicken, too much bacon really and recently some MS symptoms that had been put away (we hoped for good) started to rear their heads again and caused us to review our thinking about our diet.

We have now moved back to a template that is closer to the basic paleo template where we try to go with lean meats, oily fish, extra virgin olive oil, vegetables, some fruit (I also eat grass fed butter) and we eat some bacon once or twice a week and lots of beef and lamb from pastured animals and this is again working well for us.

We also are less scared of carbs but we try to get them in a sensible way and use them to support exercise and activity rather than just as a defacto way to start and finish the day (with more carbs at lunch time for good measure).

Ultimately, this is just still so confusing and it takes time to get things right and know what works for you. I see people do well on the low fat, high carb diets and people do well on the high fat, low carb diets. I see people do well on something in-between but we have to find what is right for us.

What I see as being important is a focus on real food & variation. I also find that most people have distinct ideas about what processed food is. For me even cheese and milk is processed (unless is is from raw milk). Soy & wheat and especially bread and pasta are highly processed foods. Slices of bread and pasta twists don’t grow on trees.

I am no expert but it is my take on this that carbs should be well aligned with energy expenditure and that carb intake of ourselves from 100 years ago or even 50 years ago was aligned with less overall food, less highly processed foods, less highly palatable foods and much, much mroe activity. Everyone now sits on their behinds doing nothing. We have 100’s of TV channels, game consoles, tablets, smartphones and social media and people are just not as active as they used to be but sugar and simple calories have gone up and the availability of these calories is at levels never seen before.

We also try to reduce this down to single points but that is doomed to failure.

– we sleep less

– we eat more

– we eat more processed, high sugar, high calorie ‘treats’

– we move less

– we are more stressed

– our food is low quality and processed

– our food is mass produced and often unhealthy in of itself

One point that I find interesting is that people tend to see weight loss on low fat or low carb and the implications that has on what is right or wrong or is this all just a case of balance and highly rewarding food options that are confusing our brains that were designed to sniff and taste and determine if something was good or bad and gorge when we could to handle the periods of low food availability.

Obviously, a hugely complicated issue and I feel fat and carbs play a part in this and that lowering carbs to match activity and keeping fat in the right ratios is all part of a bigger health picture here. I also feel that a ALL CARBS ARE BAD or ALL FAT IS BAD is just unhelpful and we need a meeting of minds here. We also need to cater for the people who are essentially broken and can’t deal with carbs or fats or whatever it may be.

I also try to keep fat and carbs separate now to some extent and eat protein and carb meals after exercise and protein and fat meals on my non training days and that seems to work well. This is almost like a bodybuilder template but again, it seems to work and keep us ticking over well.

The most important thing here is to find what works for you, make it real food based, drop processed food (and understand just what counts as processed) and try to eat in a way that is healthy and makes you happy. Oh, and get more sleep and sun.

Great article, really got me thinking. 🙂

Wow. I love it when someone responds to a post and it’s clear that the reader thinks about this stuff as much–or more–than I do. And that would be A LOT.

I think you’ve nailed many important points:

Your family’s diet changed as your lives and health changed: This is to be expected and applauded.

It’s confusing out there: As a public health nutritionist, I think that is largely the fault of my field.

Dichotomous, black-and-white thinking isn’t particularly helpful: But that’s what we have, as much in alternative nutrition as in mainstream.

And you raise a really important question: How do we help the people whose health is suffering now? And–again with my public health hat on–how do we scale up some of these ideas so that we can prevent our underserved and vulnerable populations from being “broken” in the future?

anyone remember Yard Darts?

Those really would put your eye out, right?

Great Post! Someone needs to call these “so-called experts” to task for the nonsense they spew forth. Just happy I’m not standing in front of them. I’d have to shower after listening to them.

Thanks! Sadly, the experts who don’t talk nonsense seem to get lost in the Guidelines-making process.

One more thing — and it might be a biggie:

Yes, people were likely more physically active 80 years ago, but they were also probably getting WAY MORE SLEEP. I don’t think we can discount the effects of sleep deficit and cortisol dysregulation in obesity. Nobody was staying up ’til 1am on Facebook in 1920 or watching 24-hour news.

Heck, even when *I* was a kid (and I’m only 34), there were television stations that went OFF THE AIR at 11pm. They’d be nothing but static until programming started again in the morning, or it would just say “Off air.”

Now I’m curious. I don’t think I’ve ever seen comparisons along those line, but you may have something there.

Yes, I remember the national anthem and then the white noise . . .

I think it’s becoming recognized more and more, even in academic & public forums (respected university nutrition programs, government agencies, etc) that the decades of advice to literally “base” our diets on grains and starchy vegetables are part of what’s driven the obesity epidemic. So yeah, the “authorities” are finally acknowledging that many people would be better off reducing CHO intake. HOWEVER, what is NOT being said yet — and maybe never will, unless some of the people doing the biochemical research learn to speak up much more loudly — is that while we can certainly cut back our total caloric intake via cutting back on CHO, ultimately, our calories have to come from *somewhere,* and the powers that be, at least for the moment, are still too afraid to say that we should eat more fat. (We could eat more protein, too, and to be honest, most people probably could stand to…*especially young women!*…but unless it’s all about canned tuna, boneless, skinless chicken breasts, or, heaven forbid, soy, most real, natural sources of protein come with a fair bit of fat. [Eggs, beef, pork, etc.]) It looks like Dr. Slavin said to up the fat while also dropping down the CHO, but I mean more of a wholesale “mea culpa” that I just don’t think is going to come anytime soon. My beef with all this (no pun intended!) is that they’re beginning to see the light regarding CHO, but are not really any closer to exonerating saturated fat, which, in my opinion, sort of goes hand-in-hand. (I know it doesn’t, necessarily, because the experts can simply claim that it’s okay to eat more fat — but only if it’s the hearthealthypolyunsaturatedfats [yes, one word].)

Am I making sense?

I guess all we can hope for are slow, gradual changes, and if new recommendations to cut back on sugar and other carbs and eat a little more fat mean people will back away from the Lean Cuisines and eat more salmon, olive oil, and walnuts, I guess that’s still a huge step in the right direction, even if they’re still too afraid to go for the butter and fatty steaks.

You know, for the longest time, I didn’t want to deal with the sat fat issue. I was all “let’s just get people to reduce their carbohydrate intake and who cares whether or not we let them eat sat fat.” But the more I looked at the science that was supposed to “prove” that saturated fats caused heart disease–and the more that I looked at the changes in our food supply–the more I realized that the prohibitions against saturated fat are at the heart of the whole problem. As you said, calories have to come from somewhere. If you are trying to avoid the saturated fat in eggs or meat, what else are you going to eat? Pasta, rice, beans, cereal–or in this crazy world, granola bars and lean cuisines.

This is where I run into the biggest problems with the whole “plant-based” diet thing. I don’t really have a problem with the focus on fruits and veggies (although I can drive me a little batty at times). But I still can’t figure out what the quick sources of high quality protein are supposed to be without resorting to something highly-processed. In my world, it’s an egg–dinner can be ready in less than 5 minutes.

And speaking of processed: Experts like Walter Willett have come out and said that “healthy fats” like HHPUFAs are okay, but it is clear to me that this does not ring true with a younger generation who are immediately suspicious when any nutrition expert–even Father Willett–promotes food items as highly-processed as soy and corn oil.

The bottom line is that we can’t recommend a “better quality” diet (i.e. one with fewer processed foods) without dealing with the saturated fat issue. And with the science the embarrassment that it is, we really ought to.

I get where you are coming from. Right now, I am inclined to say that we don’t need different Dietary Guidelines, we need a different kind of Dietary Guidelines. I just recently found this quote in some background material to the Surgeon General’s Report of 1979: “The goal of health education is . . . to guarantee the individual’s freedom of choice regarding his own health by giving him the reliable information he needs to make decisions about how he wants to live.” At this point, it seems we’ve failed pretty miserably in our responsibility to do this.

Yes, exactly! When I try to explain to people why soybean, safflower, corn, and other vegetable oils are not so great for cooking with (or eating in salad dressings and things like that), I give them this challenge: Name the five fattiest foods you can think of. (Give them a minute to do that.) Then ask then: Did corn make that list? No? How about soybeans? Also no? Of course not — corn and soybeans are *not* good sources of fat, so how much processing do you think it takes to get gallon-size bottles of translucent oil from them? And what are they telling us? Eat fewer processed foods. As for butter: Step 1: milk cow. Step 2: skim off cream. Step 3: churn into butter. 🙂 (No need to bore people with the biochemistry, the unstable bonds in the polyunsaturates, etc.)

I’m so with you — we tell people to consume fewer refined carbohydrates (and in some cases, fewer carbohydrates of *all* kinds), and we tell them to eat “natural,” unprocessed foods. But very few people are coming right out and saying that that, by definition, means more plain ol’ animal foods, whether it’s muscle meat, organs, bone broth, etc. (Plus, of course, tallow, lard, schmaltz.) Sure, you can also just up your intake of non-starchy vegetables, but like you said, at some point, the saturated elephant in the room has to be addressed. Because if we’re supposed to ditch the 100-calorie packs of Oreos and chocolate yogurt Special K bars, unless they publicly exonerate saturated fat, people will err too far to the other side — lots more skinless white meat chicken, fat-free dairy, and plenty of soy & canola oils on their salads. Overall, a step up from Pop-Tarts and donuts, yes, but that’s not saying much. 😉

I only disagree with you in one place: we don’t need a different kind of Dietary Guidelines. We need NO official guidelines. We need the government to get out of the business of nutrition altogether. Let’s face it: if this were a corporation that was judged on its success or failure rate (as measured by levels of obesity and/or chronic illness), the CEO would’ve been fired ages ago and the stock would be in the toilet. Nobody in their right mind would be betting their retirement funds on this company. (Clarification: I am not commenting at all on the viability of the U.S. economy or the guy we might think of as our “CEO.” I like him very much, in fact. I’m saying this only in relation to our food & nutrition policies and what stunning failures they’ve been.) I guess the problem here is, like you said, the die-hards as far as current nutrition policy goes can defend their position by saying people *would be* lean and healthy if they would just follow the darn guidelines, so the fact that they’re not just proves they’re *not* following. How nice it is for them to bring it back to obesity as a character flaw and a moral failure (greed, sloth, gluttony), rather than examining the WHOLE of the scientific evidence and eating a huge piece of sugary humble pie a la mode with extra powdered sugar on top! =)

I like to think the people behind the DGAC *think* they’re doing the right thing, and that the original intent was altruistic. But the writing’s been on the wall for a while now: IT AIN’T WORKIN’.

So where’s your blog again? 🙂

Well, the different “kind” of DGs I would support would radically different from the top-down, one-size-fits-all approach we have now. I think that any recommendations structured in that way–whether low-carb or low-fat or whatever–would result in the type of system we have now. At the same time, I am all too aware of federal nutrition programs that would be even MORE susceptible to industry influence than they are now without any safeguards that put people first (which is certainly not what our current system does). I want to put control back in the hands of the people who are ostensibly served by–or at the mercy of, depending on your viewpoint–these guidelines: schools, prisons, hospitals, community centers. Right now, if you want to help increase access to healthy food for low-income families using government funds, you have to use the definition of “healthy food” supplied by the government. I think those people should be allowed a voice in the matter and to do that, they need accurate–not politically biased–information. They need us to focus on them and their lives and circumstances; we need to hear what they need–rather than to try to control and coerce them with rules and taxes. I’m looking for a sort of controlled anarchy: community-centered, individualized, adaptable and results-oriented. I won’t pretend I have this figured out–far from it. But that’s where I am now.

“The bottom line is that we can’t recommend a “better quality” diet (i.e. one with fewer processed foods) without dealing with the saturated fat issue. ”

I have no problem promoting saturated fat. I just relate the story of Dr. Weston A. Price’s research, and how the healthy people ate butter and raw cream and eggs,etc. And then I point out all the corn and soybean fields around and how industry wants us to think these things are healthy so we’ll buy them. They catch on quickly what makes more sense and tastes better. And I tell them to cure the sugar cravings eat plenty of sat. fat. People are dumfounded to discover they’ve been conned!

Kris, I’ll just have to add: It’s not just “industry” who wants us to think these things are healthy. This is the bind we are caught in. We have promoted highly-processed vegetable oils as “healthy” from a public health standpoint for 40 years. We are having a very hard time letting go of that. It is easy to blame industry, but they are not the only ones “conning” the people.

I had forgotten about this discussion of two years ago, but have to chime in again. It strikes me that our biggest public health problem is the huge commercial food industry that takes the cheap, subsidized commodity crops and turns them into attractive un-foods that fill people up without really satisfying their nutritional hunger. They fight too and nail against anything that undermines their profits – they and the conventional agriculture industry. Their efforts to improve have been pretty feeble so far, esp. as they focus on reducing fat and salt, thanks to the wrong messages from the public health people. People are catching on, though it’s a small minority so far. My friend who owns a good health food store reports a steady stream of folks coming in for guidance on getting their health turned around with real food and appropriate supplements, after becoming totally disenchanted with what their conventional witch doctors (Ooow! Did I say that?) are telling them.

Weston Price Foundation folks are working on a restaurant evaluation form for WAPF folks to rate local places where they like to eat, and a flier to give to owners and chefs with guidelines for truly healthy (and delicious) food. Two major problems (related to what public health has been saying) – the fats/oils they use, as the natural animal sources and real olive oil are more expensive, and their lack of understanding of the value of unrefined, mineral-rich salts for flavor as well as health. And I should add their reliance on commercial flavoring concentrates instead of homemade bone broths.

I think “Paleo” is a handy moniker, with very wide interpretation these days, but it does tend to get people to eat more real food. The original Paleo guys were not very “WAPF-friendly” as they totally ignored the research of Dr. Price on isolated, truly healthy groups of people. But now several of them are much more open to the nuances of what Dr. Price learned and taught about the value of animal fats, and much more flexible in their approach.

My thoughts and links on the topic: http://www.mercyviewmeadow.org/Kris/carbohydraterestriction.htm#Paleo

Interesting times! But I’m afraid half the population may have to die off before we actually get it right.

really liked this post, keep up the good work you missed one point, people in 1909 were not taking baths with soap every day either and worked out side alot thus they were making vita d in the skin and absorbing it before it washed off and refinement is a real problem with carbs in fact I am finding it ever so difficult to determine whether a grain such as flour or bread is actually whole grain and healthy, I was going to buy some rye stone ground whole flour for baking a cake but decided against it because decided not to make that cake, but I wonder if rye cake would taste funny too, i wanted ot make a banana cake, but rye and banana doesn’t sound appetitizing. just thought of another thing, they were drinking milk and making real butter and eggs unrefined unpasturezed from grass fed cows who got lots of sun themselves so the diary would be loaded with all kinds of omega 3, and vita d, and other wonderful nutrients. sometimes I get so angry when the gov banned raw milk making it very difficult to get it without having to have a cow.

All of those are excellent points. When you think about it that way, comparing food data from 1909 to food data from 1997 REALLY doesn’t make sense. Not only were our lives very different, but our food supply (even though we are eating the same 3 macronutrients we always are: protein, fat, carb) looked very different.

Can’t remember where I read it (GCBC, maybe), but some of the food available may have been used for animal feed. This makes more sense than 500g of carb per day. According to nutritiondata.com, that’s over two pounds of corn bread, or 14 baked potatoes. And as Peter B mentioned, hunted, fished and home-grown (or poached) food isn’t necessarily accounted for.

That is possible, but also doesn’t take into account homegrown carbs either. It is true that food availability data typically includes “pet food” (as it is described on the USDA site); how this would translate or be accounted for with regard to animal feed is not described.

My point was not to argue for an absolute consumption number, but to argue for an appropriateness of different approaches to calories and macronutrients depending on context. We have very little data to indicate that an absolute low level of carbohydrate is required for an absence of obesity. We do, however, have data that indicates that calories and carbs track very neatly together–and both correspond roughly to activity levels in our pre-Dietary Guidelines population.

Enjoyed the post as always. Adele, you get stranger and stranger every time you write 🙂

Loved your description of 1970; we must be about the same age. My mother wouldn’t let me have a banana seat bike because they were “dangerous,” but she let me have ThingMaker, Clickety Clackers, and that bizarre toy with a yellow loop you put around one ankle, attached to a string with a big plastic bell on the end – you did a sort of jump rope with it, tripped yourself, and knocked your front teeth out. Do you remember those?

Thank goodness I found a link: The Footsie.

http://www.mortaljourney.com/2010/12/1970-trends/lemon-twist-or-footsie-toy

Oh, I so loved the Footsie! The heck with a standing desk … I need one of those to get my exercise in!

Or–in my case–my orthodontia rearranged.

Stranger & stranger, huh?

I on the other hand was not allowed to have Clickety Clackers because they would “put your eye out.” Yes, I remember those ankle jump-rope things. I would bolas myself with it every time and go down. I had the same problem with Chinese jump ropes. Any encountered ended with me face down with my legs in a hopeless tangle, trying not to cry while the bell rang and everybody else left the playground. Might explain the “strange” part, right?

I am about this age also, but didn’t have one of those. However, my daughter, now 25, had the same thing, but it was called a “Skip-It”! I still have it here, and will keep it for my grandkids.

Banana seats “dangerous”? That’s a good one!

I remember some rumor going around in middle school about banana seats and virginity (or lack thereof), but since all of that sort of stuff was rather unclear in my mind at the time, I didn’t worry about it.

It’s sort of hard to explain that era to my kids. They think it has something to do with hippies and the Beatles, but–at least for me–it was much more about “dressing” like a hippie (fringy vests! leather bracelets!) and the Monkees.

OMG I never heard the virginity thing! I was told that they were dangerous because the seat was long enough to carry a passenger. And somehow that was worse than what I did? which was to perch my little brother on the fender until he became heavy enough to push it into the tire, when I switched over to him sitting on the seat and me standing on the pedals.

OK, I think it was the virginity thing but my parents didn’t want to try to explain that. Sounds intriguing; I’m going to get a banana bicycle seat now and see what’s what.

Okay – THAT cracked me up. Thanks for the laugh!

I tend to question the validity of 500g of CHO in 1900… that’s a crap ton of carbs without the likes of twinkies and sodas.

that’s what I get for commenting before reading the next few lines, LOL

We assume some overestimation, because there is no “loss adjustment,” but at the same time, there is not likely to be the same level of loss as there is now in the food system (and homegrown sources of carbs would not be included). My dad grew up on a farm in Poland that would have looked like much of America at the turn of the century. He remembers a lot of potatoes.

One additional cautionary comment regarding historical dietary estimations: It’s hard to estimate the contribution of home-grown meat, poultry, eggs, and dairy to the diet, since those didn’t enter commerce. When a significantly larger portion of the population was “growning their own,” a significant portion of their diet would not be purchased and would, therefore, be difficult to accurately estimate.

Excellent point, Pete. Food availability data measures “food supplies moving from production through marketing channels.” This would exclude “home grown” and some unregulated local markets, especially early in the century.

The process has been political from the beginning! As Luise Light, in charge of developing the original Food Pyramid, explains “When our version of the Food Guide came back to us revised, we were shocked to find that it was vastly different from the one we had developed.” As she relates here http://www.whale.to/a/light.html, more grains, more processed foods, etc. That revised Pyramid was what I was told as a dietitian, was based on the latest research! That was back in the early ’80s.

Kris, thanks so much for this link! The money quote with regard to the Food Pyramid: “Our recommendation of 3-4 daily servings of whole-grain breads and cereals was changed to a whopping 6-11 servings forming the base of the Food Pyramid as a concession to the processed wheat and corn industries.Moreover, my nutritionist group had placed baked goods made with white flour — including crackers, sweets and other low-nutrient foods laden with sugars and fats — at the peak of the pyramid, recommending that they be eaten sparingly. To our alarm, in the “revised” Food Guide, they were now made part of the Pyramid’s base.”

This contrasts rather markedly with Marion Nestle’s contention that it was primarily the meat and dairy industries that influenced the final content of the Food Pyramid.

Don’t forget to tell you readers about OR

“Sugar is toxic” is part of the State Diet. It is may well be were alternative nutrition community meets the USDA. However, while trying to avoid ad hominem, a pediatric endocrinoligist who admits failure and goes running to the government for taxation or other punishment is in the same ballpark as Mark Bittman (and is probably sure that somewhere down the line, the indiscretions a the county fair will kill you). For that part of the picture, although supporting the importance of carbs, you might like my take on fructose, just published in prelim form at http://nutritionandmetabolism.com