A COMPOSER'S BLOG

Tony Haynes, composer/creative director of the Grand Union Orchestra, tells the inside story of his music for the orchestra, its musicians and colourful history.

52: After Brexit

I’m writing this in Marseille, in the aftermath of Britain’s devastating vote to leave the European Union. How are we to respond to this as musicians, and what can we achieve through the power of music to help alleviate its consequences? This, as it happens, is the theme of the song I referred to last month, and the subject of my very first Post, If Music Could. This is not the place to go into why the country seems to have decided to destroy itself, but we are certainly faced with a challenge of a different order from any we have previously experienced…

Marseille is a strangely appropriate place to begin to consider this challenge – not least because of course it gave the French Revolution its stirring marching song, the Marseillaise! However, the song that better encapsulates the kind of spirit and determination we now need is Ça Ira, which emerged on the streets of Paris during the days of the Commune. As far as Grand Union is concerned, we will continue to live up to our name, producing work that confronts prejudice and intolerance, and shows the creative benefits a multicultural society can enjoy.

This version of Ça Ira comes from the Grand Union Orchestra’s third big touring show (and second CD) Freedom Calls. With lyrics by Caribbean, South African and Chilean writers, it covered subjects ranging from the Slave Trade to the military coup in Chile (1973) and Apartheid – typical Grand Union territory!

I wanted to write a powerful ‘overture’ to set the tone of the show with a relentless, progressive energy; the iconic song of the French Revolution 200 years earlier Ça Ira (roughly translated ‘It’ll be OK, it’ll be OK, people go around saying over and over; in spite of the turncoats, everything will turn out well’) seemed to have the potential to provide material for this:

However, I found I didn’t need the whole song (or the words) to get its spirit across – just the first four notes, in fact, and the rising phrase (x) at the beginning of bar 3! Given the show’s themes, it seemed appropriate that drums from different countries around the world should frame the piece, especially if they were played by people whose communities were in some way involved historically or culturally with freedom movements. In the opening section, therefore, they enter one by one with a flourish before settling down into a steady rhythm, introducing in turn a series of bass instruments hammering out the ‘ah ça ira’ notes and improvising around them:

However, I found I didn’t need the whole song (or the words) to get its spirit across – just the first four notes, in fact, and the rising phrase (x) at the beginning of bar 3! Given the show’s themes, it seemed appropriate that drums from different countries around the world should frame the piece, especially if they were played by people whose communities were in some way involved historically or culturally with freedom movements. In the opening section, therefore, they enter one by one with a flourish before settling down into a steady rhythm, introducing in turn a series of bass instruments hammering out the ‘ah ça ira’ notes and improvising around them:

- congas (Sarah Laryea, Ghana) – cello (Paul Jayasinha)

- bongos (Ken Johnson, Trinidad) – bass clarinet (Keith Morris)

- timbales (Josefina Cupido, Spain) – baritone sax (Gerry Hunt)

- timpani (Claude Deppa, South Africa) – piano LH (Tony Haynes)

- drum kit (Dave Barry) – bass guitar (Dave Clarke, African-American)

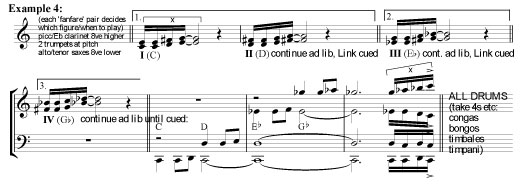

The deep piano line also sketches out the rising chords (suggested by the scale figure x) that are about become a major feature of the piece:  A unison link based on the ‘ah ça ira’ notes leads into clear statement of each of these chords in turn (but with C in bass throughout), in the course of three appearances – introducing successively D, Eb and Gb major chords into the mix for the trombone soloist:

A unison link based on the ‘ah ça ira’ notes leads into clear statement of each of these chords in turn (but with C in bass throughout), in the course of three appearances – introducing successively D, Eb and Gb major chords into the mix for the trombone soloist:  This solo is intended to represent an orator or leader arousing the crowd to action – magnificently embodied here by the incomparable Rick Taylor. The drama (and the harmonic ambiguity) is intensified by short cries or ‘fanfares’ from the rest of the wind and brass, based on the rising scale (x) from the song, but adjusted to outline the four different harmonies. The idea is that they are cumulative, based just on C and D to start with, then adding E flat after the second link, and finally G flat – giving the solo trombone the equivalent harmonic freedom. At this point also, the drums gradually drop out, while the backing instruments add a new element of colour. This is considerably enhanced on stage by the movement of musicians changing instruments (eg as cello, bass clarinet, baritone and timps become piccolo/E flat clarinet, trumpets, alto/tenor sax etc!), and as the leader of each pair signals which of the 2, 3 or 4 phrases they are to play next:

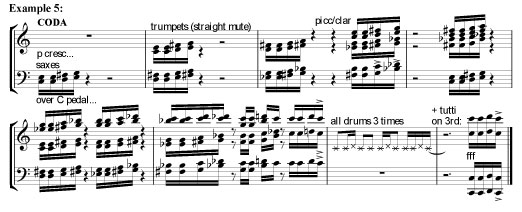

This solo is intended to represent an orator or leader arousing the crowd to action – magnificently embodied here by the incomparable Rick Taylor. The drama (and the harmonic ambiguity) is intensified by short cries or ‘fanfares’ from the rest of the wind and brass, based on the rising scale (x) from the song, but adjusted to outline the four different harmonies. The idea is that they are cumulative, based just on C and D to start with, then adding E flat after the second link, and finally G flat – giving the solo trombone the equivalent harmonic freedom. At this point also, the drums gradually drop out, while the backing instruments add a new element of colour. This is considerably enhanced on stage by the movement of musicians changing instruments (eg as cello, bass clarinet, baritone and timps become piccolo/E flat clarinet, trumpets, alto/tenor sax etc!), and as the leader of each pair signals which of the 2, 3 or 4 phrases they are to play next:  The drums now take over again, exchanging phrases in a relentless ebb and flow of rhythm, to which the wind and brass then add punchy figures combining the 4-note ‘ah ça ira’ melody and rhythm with the harmonised ‘fanfares’. Finally, a double-time version of the Link (Ex 3) on drums, played 3 times, ends with both groups punching the message home together:

The drums now take over again, exchanging phrases in a relentless ebb and flow of rhythm, to which the wind and brass then add punchy figures combining the 4-note ‘ah ça ira’ melody and rhythm with the harmonised ‘fanfares’. Finally, a double-time version of the Link (Ex 3) on drums, played 3 times, ends with both groups punching the message home together:

A poignant reflection

Freedom Calls was premiered at the Edinburgh Festival in 1986, and recorded soon after. In 1989, as part of the French celebrations of the bicentenary of the Revolution, the Grand Union Orchestra was invited to perform the work in the idyllic setting of the beach in Boulogne, with the sun going down behind us over the English Channel as the show came to an end…

Note on this recording

This recording has been edited from the original longer version, to be heard on the CD, which does in fact include the song, as well as a section introducing other instruments used later in the show (notably charango and steel pans). However, this analysis is based on the ‘generic’ (shortened) version now played in other contexts by the Grand Union Orchestra. It is notable that every player – in the spirit of equality and fraternity! – gets the same part (just two pages, transposed as necessary), so the instrumentation is flexible and the arrangement improvised – or ‘busked’ by the musicians on stage that night!

This Post is a revised version of one originally published about 3 years earlier.